Birmingham and Midland Institute

The Birmingham and Midland Institute (popularly known as the Midland Institute) (grid reference SP066870), is an institution concerned with the promotion of education and learning in Birmingham, England. It is now based on Margaret Street in Birmingham city centre. It was founded in 1854 as a pioneer of adult scientific and technical education (General Industrial, Commercial and Music); and today continues to offer arts and science lectures, exhibitions and concerts. It is a registered charity. There is limited free access to the public, with further facilities available on a subscription basis.

The Coat of Arms of The Birmingham & Midland Institute [1] | |

| Motto | Latin: Sine Fide Doctrina |

|---|---|

Motto in English | Endless Learning |

| Established | 1854 by Act of Parliament |

| President | Sir David Cannadine |

| Vice-president | Dr Serena Trowbridge, Samina Ansari |

| Location | , , United Kingdom |

History

Following the demise of the Birmingham Philosophical Institution, founded c.1800,[2] which was wound up in 1852, The Birmingham & Midland Institute was founded in 1854 by Act of Parliament "for the Diffusion and Advancement of Science, Literature and Art amongst all Classes of Persons resident in Birmingham and the Midland Counties", as the council had rejected the Free Libraries and Museums Act 1850. The principal promoter of the project was Arthur Ryland, while others prominent in its establishment included George Dixon, John Jaffray, and Charles Tindal.[3] The Institute commissioned architect Edward Middleton Barry to design a building next to the Town Hall in Paradise Street. The foundation stone was laid by Prince Albert in November 1855.[4] With the building half-completed, in January 1860, the first public museum was opened in the Institute. Immediately the Council reversed its decision, and adopting the Act, negotiated with the Institute to buy the rest of the site. The other half of the planned building (up to Edmund Street) was completed by William Martin using the intended façade but redesigned behind. The municipal Public Library opened in 1866, but burned down during the building of an extension in 1879. Exhibitions of art were moved from the Institute to Aston Hall during rebuilding. In 1881 John Henry Chamberlain (architect and Honorary Secretary of the Institute) completed an extension to the Institute, in the gothic style.

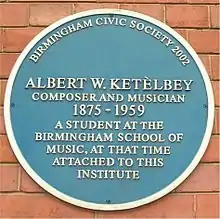

When the premises at Paradise Street were demolished, in 1965 as part of the redevelopment of the city centre, the Institute moved to 9 Margaret Street. Margaret Street was originally the home of the private Birmingham Library, but it became part of the Midland Institute in 1956, when members voted for it to be subsumed into the Institute. The Birmingham Library premises were built in 1899 to the designs of architects Jethro Cossins, F. B. Peacock and Ernest Bewley, and is now a Grade II* listed building.[5] A blue plaque on this building commemorates Albert Ketèlbey, who studied at the Birmingham School of Music when it was part of the Institute.

Charles Dickens was an early president after giving recitals in the Town Hall to raise funds. The Institute contains the 100,000 volumes of the Birmingham Library, founded in 1779.

In 1876, the subject of "phonography" (or Pitman shorthand) was introduced to the Institute. During the first session, Marie Bethell Beauclerc, the first female shorthand reporter in England, taught 90 students. By 1891, there were over 300 students, predominately male, attending her phonography classes.

A School of Metallurgy was set up in the Institute by G. H. Kenrick in 1875. This was spun-out from the Institute in 1895 as the Birmingham Municipal Technical School, now Aston University.[6]

Weather recording

In 1837 A. Follett Osler (Fellow of the Royal Society) gave a presentation on readings taken by a self-recording anemometer and rain gauge he had designed. He was funded by the Birmingham Philosophical Institution to design instruments and record meteorological data. He gave instruments to the BPI and the Institute starting an almost unbroken record of weather measurements from 1869 (to 1954, date of source material). In 1884 the Institute leased Perrott's Folly, a 100-foot monument in Edgbaston, for use as an observatory. In 1886 the City of Birmingham Water Department allowed the Institute to erect instruments in an observatory on the nearby covered water reservoir. By 1923 a daily weather map was on display outside the institute. The Observatory was still in operation in 1954 (date of source material). The Observatory received funding from the City Council, and the Air Ministry at various times.

Affiliated organisations

Various independent societies are affiliated to the BMI including:

- The Birmingham Civic Society, The Birmingham Philatelic Society, Ex Cathedra, Institute Ramblers, Birmingham and Warwickshire Archaeological Society, Midland Spaceflight Society, Workers Educational Association, Dickens Fellowship, The Birmingham and Midland Society for Genealogy and Heraldry, the Society for the History of Astronomy, The Victorian Society (Birmingham & West Midlands).

Presidents

The office of president is held by some person of eminence in the arts, sciences or public life. The presidential term usually lasts one year, but can be extended up to three years; and one of the presidential tasks is to deliver an inaugural address. In the early years, the president was usually a person of prominence in the West Midlands, but the election of Charles Dickens in 1869 raised the institute's profile, and it became the practice to invite a person of national renown to serve.[7] The following is the list of presidents:

- 1854 (1st President): George Lyttelton, Baron Lyttelton of Hagley

- 1855 (2nd): Frederick Gough, 4th Baron Calthorpe, politician

- 1856 (3rd): William Legge, 5th Earl of Dartmouth, Conservative politician

- 1857 (4th): Edward Littleton, 1st Baron Hatherton, politician

- 1858 (5th): William Ward, 11th Baron Ward, industrialist, landowner and benefactor

- 1859 (6th): William Henry Leigh, 2nd Baron Leigh, politician

- 1860 (7th): Sir Francis Scott, 3rd Baronet, landowner

- 1861 (8th): Arthur Ryland, Lord Mayor of Birmingham (1860)

- 1862 (9th): Sir John S. Pakington, Conservative politician

- 1863 (10th): William Scholefield, businessman and Liberal politician

- 1864 (11th): Charles Adderley, 1st Baron Norton, politician

- 1865 (12th): John Wrottesley, 2nd Baron Wrottesley, astronomer

- 1866 (13th): Dudley Ryder, 2nd Earl of Harrowby

- 1867 (14th): Matthew Davenport Hill, lawyer and penologist

- 1868 (15th): Thomas Anson, 2nd Earl of Lichfield, politician

- 1869 (16th): Charles Dickens, author

- 1870 (17th): Lyon Playfair, scientist and Liberal politician

- 1871 (18th): T. H. Huxley, biologist

- 1872 (19th): Canon Charles Kingsley, author of Westward Ho! (1855) and The Water-Babies (1863)

- 1873 (20th): Sir Henry Rawlinson, 1st Baronet, army officer and politician

- 1874 (21st): Sir John Lubbock, banker, politician, philanthropist, and scientist

- 1875 (22nd): Professor Henry Fawcett, statesman and economist

- 1876 (23rd): John Morley, Liberal statesman and newspaper editor

- 1877 (24th): Professor John Tyndall, physicist

- 1878 (25th): Arthur Stanley, Dean of Westminster

- 1879 (26th): Professor Max Müller, philologist and Orientalist

- 1880 (27th): Thomas Baring, 1st Earl of Northbrook, politician

- 1881 (28th): Professor Sir William Siemens, engineer

- 1882 (29th): J. A. Froude, historian and novelist

- 1883 (30th): Sir William Thomson (afterwards Baron Kelvin), mathematical physicist and engineer

- 1884 (31st): James Russell Lowell, poet and United States Minister to Great Britain

- 1885 (32nd): Edward White Benson, Archbishop of Canterbury

- 1886 (33rd): Sir Frederick Branwell, civil and mechanical engineer

- 1887 (34th): Sir John Seeley, essayist and historian

- 1888 (35th): Sir Arthur Sullivan, composer

- 1889 (36th): Sir Henry Roscoe, chemist

- 1890 (37th): Edward Augustus Freeman, historian

- 1891 (38th): Sir Robert Ball, astonomer

- 1892 (39th): W. E. H. Lecky, historian

- 1893 (40th): Sir Edwin Arnold, poet and journalist

- 1894 (41st): The Right Reverend, William Boyd Carpenter, Bishop of Ripon

- 1895 (42nd): William Boyd Carpenter, Bishop of Ripon

- 1896 (43rd): The Right Honourable, G. J. Goschen, MP, politician

- 1897 (44th): Frederic Harrison, historian

- 1898 (45th): Sir Norman Lockyer, astronomer

- 1899 (46th): Sir John Evans, archaeologist and geologist

- 1900 (47th): Mandell Creighton, Bishop of London

- 1901 (48th): Archibald Primrose, 5th Earl of Rosebery, politician

- 1902 (49th): The Right Honourable, Sir Mountstuart Grant Duff, politician

- 1903 (50th): Joseph Hodges Choate, lawyer and United States Ambassador to the United Kingdom

- 1904 (51st): Sir Oliver Lodge, physicist

- 1905 (52nd): Charles Gore, 1st Bishop of Birmingham

- 1906 (53rd): Richard Webster, Viscount Alverstone, Lord Chief Justice

- 1907 (54th): Lord Curzon of Kedleston, politician

- 1908 (55th): Sir William Blake Richmond, artist

- 1909 (56th): The Right Honourable, Alfred Lyttelton, politician

- 1910 (57th): Professor Sir George Darwin, astronomer

- 1911 (58th): Cosmo Gordon Lang, Archbishop of York

- 1912 (59th): General Sir Ian Hamilton, army officer

- 1913 (60th): The Right Honourable, The Viscount Milner, politician

- 1914 (61st): Sir Frederick Treves, surgeon

- 1915 (62nd): Sir Herbert Beerbohm Tree, actor and theatre manager

- 1916 (63rd): The Right Reverend and Right Honourable, Arthur Winnington-Ingram, KCVO, Bishop of London

- 1917 (64th): Admiral The Right Honourable, The Lord Beresford, GCB GCVO, admiral and politician

- 1918 (65th): Walter Hines Page, US Ambassador to the Court of St James'

- 1919 (66th): Sir Rickman Godlee, KVCO, surgeon

- 1920 (67th): John W. Davis, US Ambassador to the Court of St James'

- 1921 (68th): Guglielmo Marconi, inventor and electrical engineer

- 1922 (69th): The Honourable Sir Charles Algernon Parsons, engineer

- 1923 (70th): Austen Chamberlain, awarded the 1925 Nobel Peace Prize

- 1924 (71st): Sir Reginald Blomfield, architect

- 1925 (72nd): F. E. Smith, Earl of Birkenhead, statesman

- 1926 (73rd): Sir William Bragg, OM KBE PRS, physicist

- 1927 (74th): The Right Honourable, The Viscount Grey of Fallodon, KG PC DL FZS, politician

- 1928 (75th): The Right Honourable, The Earl of Crawford, KT PC DL FRS FSA, politician

- 1929 (76th): Sir Frank Dyson, Astronomer Royal

- 1930 (77th): The Most Honourable, The Marquess of Zetland, KG GCSI GCIE PC JP DL, politician

- 1931 (78th): The Right Honourable, The Viscount Hewart, Kt PC, Lord Chief Justice of England

- 1932 (79th): The Right Reverend, Ernest Barnes, FRS, Lord Bishop of Birmingham

- 1933 (80th): Sir James Jeans, physicist, astronomer and mathematician

- 1934 (81st): The Lord Moynihan, surgeon

- 1935 (82nd): Stanley Bruce, High Commissioner of Australia to the United Kingdom (formerly Prime Minister of Australia)

- 1936 (83rd): Sir Josiah Stamp, industrialist and banker

- 1937 (84th): The Right Honourable, The Lord Sempill, AFC, air pioneer

- 1938 (85th): The Right Honourable, The Earl of Dudley, MC TD, politician

- 1939 (86th): Thomas Horder, Baron Horder, physician

- 1940 (87th): Sir H. Walford Davies, Master of the King's Music

- 1941 (88th): The Right Honourable, The Viscount Bennett, PC KC, former Prime Minister of Canada

- 1942 (89th): John Sankey, 1st Viscount Sankey, judge and Lord Chancellor

- 1943 (90th): Ernle Chatfield, 1st Baron Chatfield, Admiral of the Fleet

- 1944 (91st): Norman Birkett, judge and politician

- 1945 (92nd): Sir Charles Galton Darwin, physicist

- 1946 (93rd): Edward Woods, Bishop of Lichfield

- 1947 (94th): Sir Richard Winn Livingstone, classical scholar and university administrator

- 1948 (95th): The Right Honourable, Lord Iliffe, newspaper magnate

- 1949 (96th): Sir Raymond Priestley, geologist and Antarctic explorer

- 1950 (97th): Leo Amery, politician and journalist

- 1951 (98th): Sir Raymond Evershed, judge and Master of the Rolls

- 1952 (99th): Sir John Russell CMG GCVO, diplomat and ambassador

- 1953 (100th): John Boyd Orr, 1st Baron Boyd-Orr, biologist, politician, awarded the 1949 Nobel Peace Prize

- 1954 (101st): Oliver Lyttelton, 1st Viscount Chandos, businessman and politician

- 1955 (102nd): Sir Gerald Kelly PRA, painter

- 1956 (103rd): Sir Cecil Maurice Bowra, CH, FBA, classical scholar

- 1957 (104th): The Right Honourable, The 1st Earl Attlee, politician

- 1958 (105th): M André Maurois, author

- 1959 (106th): The Right Honourable, The Viscount Radcliffe, Law Lord

- 1960 (107th): Sir Alexander Fleck,industrial chemist

- 1961 (108th): The Right Honourable, The Lord Rennel of Rodd, World War II veteran

- 1962 (109th): Sir Robert Aitken, physician

- 1963 (110th): Charles Lyttelton, 10th Viscount Cobham, Governor-General of New Zealand

- 1964 (111th): Dame Ninette de Valois, choreographer

- 1965 (112th): Sir Donald Finnemore, Liberal politician

- 1966 (113th): Sir Lawrence Bragg, physicist

- 1967 (104th): Sir Eric Clayson, businessman

- 1968 (115th): The Right Reverend Leonard Wilson, The Lord Bishop of Birmingham

- 1969 (116th): Sir Peter Venables, Aston University’s first Vice-Chancellor

- 1970 (117th): Sir Peter Venables, Aston University’s first Vice-Chancellor

- 1971 (118th): The Right Honourable, Lord King's Norton, aeronautical engineer

- 1972 (119th): The Right Honourable, Jo Grimmond PC, Liberal politician

- 1973 (120th): The Reverend Canon R. G. Lunt

- 1974 (121st): Sir Lionel Russell, Chief Education Officer, Birmingham, 1946-1968

- 1975 (122nd): Dr J. A. Pope

- 1976 (123rd): Honorary Alderman, Mrs. E. V. Smith

- 1977 (124th): Sir Peter Scott, ornithologist

- 1978 (125th): Dr Beryl Foyle, Managing Director of Boxfoldia

- 1979 (126th): Sir Adrian Cadbury, KT, Chairman of Cadbury

- 1980 (127th): Mr Yehudi Menuhin, KBE, violinist and conductor

- 1981 (128th): Mr Wynford Vaughan-Thomas, broadcaster

- 1982 (129th): Miss Evelyn Laye, CBE, actress

- 1983 (130th): Sir David Willcocks, musician and composer

- 1992 (139th): Rachel Waterhouse, local historian and activist

- 1993 (140th): The Most Reverend Maurice Couve de Murville, Roman Catholic Archbishop of Birmingham

- 1994 (141st): Sir Michael Checkland, former Director General of the BBC

- 1995 (142nd): Mr Joe Hunt

- 1996 (143rd): Sybil, Lady Thompson

- 1997 (144th): Dr Carl Chinn, historian

- 1998 (145th): Mr Peter Donohoe, classical pianist

- 1999 (146th): Fay Weldon, author

- 2000 (147th): Penelope Lyttelton, Viscountess Cobham

- 2001 (148th): Professor Peter Willmore, astronomer

- 2002 (149th): Dr Desmond King-Hele, physicist

- 2003 (150th): Thomas Trotter, City Honorary Organist

- 2004 (151st): John Lyttelton, 11th Viscount Cobham

- 2005 (152nd): The Very Reverend Dr Peter Berry, Provost of Birmingham

- 2006 (153rd): Mr Brian Walden, journalist

- 2007 (154th): Miss Jenny Uglow, historian

- 2008 (155th): Professor Stanley Wells CBE, Shakespearian scholar

- 2009 (156th): Sir Arnold Wolfendale, astronomer

- 2010 (157th): The Right Reverend, David Urquhart, The Lord Bishop of Birmingham

- 2011 (158th): Sir Ralph Kohn, medical scientist

- 2012 (159th): The Right Reverend, Michael Dickens Whinney, Bishop of Southwell

- 2013 (160th): Christopher Lyttelton, 12th Viscount Cobham,

- 2014 (161st): Mr Adrian Shooter, CBE, transport executive

- 2015 (162nd): Ms Lyndsey Davis, novelist

- 2016 (163rd): Julian Lloyd Webber, musician

- 2017 (164th): Roger Ward, political historian

- 2018 (165th): Simon Callow, actor

- 2019 (166th): Jonathan Coe, novelist

- 2020 (167th): Dr Carl Chinn MBE, historian

- 2021 (168th): Professor Sir David Cannadine, author & historian

References

- "Birmingham and Midland Institute". Heraldry of the World. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- Anon. (1830). An Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Birmingham, with some account of its environs, and forty-four views of the principal public buildings, etc. Birmingham: Beilby, Knott & Beilby. p. 185.

- Waterhouse 1954, pp. 11–23.

- "Birmingham and the Midland Institute". The Illustrated London News. Vol. 27, no. 771. 24 November 1855.

- Historic England, "Birmingham and Midland Institute (1343095)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 5 October 2016

- "History and Traditions". Aston University. 2010. Retrieved 9 August 2010.

- Waterhouse 1954, p. 46.

Sources

- Davies, Stuart (1985). By the Gains of Industry: Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, 1885–1985. Birmingham: Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. ISBN 0-7093-0131-6.

- Groves, Peter (1987). Exploring Birmingham: a guided tour. Oldbury: Meridian. ISBN 1-869922-00-X.

- Holyoak, Joe (1989). All About Victoria Square. Birmingham: The Victorian Society, Birmingham Group. ISBN 0-901657-14-X.

- Waterhouse, Rachel E. (1954). The Birmingham and Midland Institute, 1854–1954. Birmingham: Birmingham and Midland Institute.