Vocal school

A vocal school, blab school or ABC school or old-time school was a type of children's primary school at some remote rural places in North America, outdated and obsolete as the 19th century progressed. The school children recited (blabbed) their lessons out loud separately or in chorus with others as a method of learning.

Etymology and word origin

Blab is the shortened form of the word "blabber", meaning to talk much without making sense.[3] Middle English had the noun blabbe, "one who does not control their tongue".[4]

A blab school was where the school children repeated back their teacher's oral lesson at the top of their voices. The school children vocalized out their lesson in "Chinese fashion" as harmonized voices in unison.[5] In more elegant terms, instead of saying they were blab schools they were referred to as vocal schools.[6]

The neighbors of such a children's school of the 19th century would hear all the noise coming from the school of the children reciting the teacher's lesson aloud, and then dubbed the schools "blab" schools since it sounded like "blab-blab-blab".[7][8]

Description

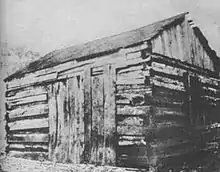

A blab school was popular in frontier days of the American West, since many settlers could not read.[9] These one-room schools were called "old field" schools and were log cabins, many times with just dirt floors.[10] The students sat on wooden backless benches.[11] This type of school was referred to as an "Old-time School" in the Appalachian region of Virginia in the 19th century.[12]

A blab school was basically without books and paper for the students.[9] The schooling consisted of a teacher, with perhaps one or two books, speaking a short oral lesson and the schoolchildren reciting it back with a loud voice several times until memorized.[9][3] The only requirement needed to become a teacher was to know how to read.[3]

Reciting the information learned was a form of entertainment in frontier days as well as a means of learning.[9] In those days paper was scarce so memorizing was the preferred method over writing things down.[13] The subjects of reading, writing, and arithmetic were the basic ABC items in the 19th century typically learned by the young children reciting out loud the lesson. In blab schools it was typical for a teacher to comment about a child grasping the lesson. This student was referred to as a "leather-head" and was awarded with praise from the teacher.[9]

In many of the "ABC schools" of the United States each pupil was to recite first thing in the morning of the new school day the lesson they learned of their homework assignment of the previous day. The ambitious ones reached the school house by sunrise since they recited in the order of their arrival in the morning. The school rule was "first come, first called" and after a student's recital the teacher called out "Next" as they knew the order of each student's arrival.[12]

The method of reciting one's lesson to memorize it was referred to as "loud studying".[13] Many people of the time believed that listening to one "blabbing" out loud their lesson benefitted the education of the other students.[13] Teachers were not shy in dishing out punishment to those who did not loudly shout out their lesson.[14] The teacher would walk around the classroom with a wooden switch or paddle when the students were reciting and use it on the child if the student was not loud enough to the teacher's pleasing.[15][16]

Abraham Lincoln

U.S. president Abraham Lincoln learned his ABCs when he attended a vocal school which he walked to in his youth.[19][20] The school he first attended was at least a mile from his home.[2] His first two teachers were Zachariah Riney and Caleb Hazel, who taught from a windowless schoolhouse.[21] Another teacher of Lincoln was Azel Waters Dorsey (1784-1858) who taught him for 6 months in 1824 in a blab school in Spencer County, Indiana.[22]

Lincoln learned first from spelling books. It was customary to learn first to spell all the words of the spelling books and recite several times before advancing to read other books.[23] Lincoln studied Dillworth's Speller and Webster's Old Blueback.[24] Later then he advanced to reading Murray's English Reader.[24]

Lincoln was noted for shouting out his reading lesson on the path from his home to the blab school and could be heard for a considerable distance.[25] He had the habit of reading anything aloud.[15] Between the ages of 11 and 15, Lincoln went to school occasionally between his obligated home duties.[26] All of Lincoln's schooling combined in various blab schools amounted to less than a year.[24][27] Many times the blab school Lincoln attended did not even have a teacher; instead, the older, more advanced students, often teenagers, taught the younger children.[28]

Footnotes

- Howard Taylor (2014). "Learning Like Abe: Read'n, Writ'n and Cipher'n". Abraham Lincoln and Other U.S. Historical and Related Resources. Archived from the original on 2012-05-19. Retrieved 2014-04-27.

- Osborne & Boyce 2011, p. 19.

- Osborne & Boyce 2011, p. 20.

- "Online Etymology Dictionary". Douglas Harper. 2001–2014. Retrieved 2014-04-24.

- Civic Press 1920, p. 301.

- Evangelical Alliance for the United States of America 1890, p. 83.

- Carnegie 2006, p. 70.

- Cary 2011, p. 6.

- Thomas 2013, p. 91.

- Addington 1914, p. 4.

- Facts On File 2009, p. 16.

- Addington 1914, p. 5.

- Thomas 2013, p. 92.

- Feldman 2001, p. 17.

- Barton 1920, p. 32.

- Townley 2004, p. 70.

- Fleming 2008, p. 7.

- Griffin 2009, p. 40.

- "Abraham Lincoln's First School". Kentucky Historical Society. 2014. Retrieved 2014-04-26.

- Pascal 2008, p. 24.

- Freedman 1989, p. 20.

- "Abraham Lincoln's Teacher - Azel Waters Dorsey, Huntsville, IL". Waymarking.com. Groundspeak, Inc. 2014.

- Angle 1990, p. 23.

- Angle 1990, p. 24.

- Hubert 1920, p. 215.

- Oates 2009, p. 178.

- Burlingame 2009, p. 331.

- Savory 2010, p. 13.

Bibliography

- Addington, Robert Milford (1914). The Old-time School in Scott County.

- Angle (1990). The Lincoln Reader. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80398-7.

- Barton, William Eleazar (1920). The soul of Abraham Lincoln. George H. Doran Company.

- Burlingame, Michael (2009). Abraham Lincoln: A Life. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-9467-1.

- Carnegie, Dale (2006). Public Speaking for Success. Penguin Group US. ISBN 978-1-101-11856-6.

- Cary, Barbara (2011). Meet Abraham Lincoln. Random House Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-307-78694-4.

- Civic Press (1920). Town & County Edition of The American City. Civic Press.

- Evangelical Alliance for the United States of America, General Christian Conference (1890). National Needs and Remedies. Baker & Taylor Company.

- Facts On File, Incorporated (2009). Abraham Lincoln. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4381-2612-8.

- Feldman, Ruth Tenzer (2001). Don't Whistle in School: The History of America's Public Schools. Twenty-First Century Books. ISBN 978-0-8225-1745-0.

- Fleming, Candace (2008). The Lincolns: A Scrapbook Look at Abraham and Mary. Schwartz & Wade Books. ISBN 978-0-375-83618-3.

- Freedman, Russell (1989). Lincoln: A Photobiography. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-547-53220-2.

- Griffin, John Chandler (2009). Mr. Lincoln and His War. Pelican Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4556-0905-5.

- Hubert, Philip Gengembre (1920). The Atlantic Monthly. Atlantic Monthly Co.

- Oates, Stephen B. (2009). With Malice Toward None: The Life of Abraham Lincoln. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-195224-1.

- Osborne, Mary Pope; Boyce, Natalie Pope (2011). Magic Tree House Fact Tracker #25: Abraham Lincoln: A Nonfiction Companion to Magic Tree House #47: Abe Lincoln at Last!. Random House Children's Books. ISBN 978-0-375-98861-5.

- Pascal, Janet (2008). Who Was Abraham Lincoln?. Penguin Group US. ISBN 978-1-4406-8813-3.

- Savory, Tanya (2010). Abraham Lincoln: A Giant Among Presidents (Townsend Library). Townsend Press. ISBN 978-1-59194-180-4.

- Thomas, Sue (2013). A Second Home: Missouri's Early Schools. University of Missouri Press. ISBN 978-0-8262-6566-1.

- Townley, Claudine (2004). How to Prepare for the FCAT: Grade 10 Florida Comprehensive Assessment Test in Reading and Writing. Barron's Educational Series. ISBN 978-0-7641-2746-5.