Black Vaudeville

Black Vaudeville is a term that specifically describes Vaudeville-era African American entertainers and the milieus of dance, music, and theatrical performances they created. Spanning the years between the 1880s and early 1930s, these acts not only brought elements and influences unique to American black culture directly to African Americans but ultimately spread them beyond to both white American society and Europe.

Vaudeville had what were known as "circuits", venues that booked touring entertainers. Racism made it difficult for a black performer to be accepted into the white circuits of the day. Eventually, black circuits, known colloquially as "chitlin' circuits", emerged to link black performers and entertainment opportunities.

Origin

Pat Chappelle (1869-1911) was a black showman from Jacksonville, Florida who helped pave the way for African-American performers. He learned the show business ropes from his uncle Julius C. Chappelle, who allowed him to meet Franklin Keith and Edward F. Albee, producers of vaudeville. Pat ended up working for Keith and Albee as a piano player. During his vaudeville debut, he met Edward Elder Cooper who was a journalist interested in black entertainment and the first to write a journal about the African-American race in 1891.

In 1898, Chappelle organised his first traveling show, the Imperial Colored Minstrels (or Famous Imperial Minstrels),[1] which featured comedian Arthur "Happy" Howe and toured successfully around the South.[2][3] Chappelle also opened a pool hall in the commercial district of Jacksonville. Remodeled as the Excelsior Hall, it became the first black-owned theater in the South, reportedly seating 500 people.[4][5]

In 1899, following a dispute with the white landlord of the Excelsior Hall, J. E. T. Bowden, who was also the Mayor of Jacksonville, Chappelle closed the theatre and moved to Tampa, where he – with fellow African-American entrepreneur R. S. Donaldson – opened a new vaudeville house, the Buckingham, in the Fort Brooke neighborhood. The Buckingham Theatre opened in September 1899, and within a few months was reported to be "crowded to the doors every night with Cubans, Spaniards, Negroes and white people".[4] In December 1899 Chappelle and Donaldson opened a second theatre, the Mascotte, closer to the center of Tampa.[4][1] A different reporter said, “These theaters have proven themselves to be miniature gold mines.”

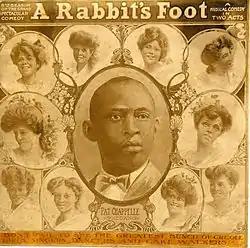

His next project was a touring show called A Rabbit's Foot. The difference between this tour and previous ones were the cast was sixty people, and all performers would be comfortable. If a black performer was able to tour in a white circuit, they would not be allowed to sleep in the hotels when they stopped to rest, because the hotels would not allow it. They slept on the bus because it was better than the floor.[6] On Chappelle's tour, the Freeman described their travel accommodations as “their own train of new dining and sleeping cars, which ‘tis said, when finished, will be a ‘palace on wheels.” Like his Famous Imperial Minstrel show, A Rabbit's Foot contained minstrel and a variety of acts while maintaining the expected vaudeville staging flare. Chappelle offered a show for everyone.[7]

In summer 1900, Chappelle decided to put the show into theatres rather than under tents, first in Paterson, New Jersey, and then in Brooklyn, New York. In October 1901, the company launched its second season, with a roster of performers again led by comedian Arthur "Happy" Howe, and toured in Alabama, Mississippi, Georgia and Florida. The show grew in popularity throughout the early years of the century, and played in both theatres and tents.[4][1] Trading as Chappelle Bros.,[3] Pat Chappelle and his brothers, James E. Chappelle and Lewis W. Chappelle, rapidly organised a small vaudeville circuit, including theatre venues in Savannah, Georgia, as well as Jacksonville and Tampa. By 1902 it was said that the Chappelle Bros. Circuit had full control of the African-American vaudeville business in that part of the country, "able to give from 12 to 14 weeks [of employment] to at least 75 performers and musicians" each season.[2] Chappelle stated that he had "accomplished what no other Negro has done - he has successfully run a Negro show without the help of a single white man."[4] As his business grew, he was able to own and manage multiple tent shows, and the Rabbit's Foot Company would travel to as many as sixteen states in a season. The show included minstrel performances, dancers, circus acts, comedy, musical ensemble pieces, drama and classic opera,[8] and wasknown as one of the few "authentic negro" vaudeville shows around. It traveled most successfully in the southeast and southwest, and also to Manhattan and Coney Island.[9]

By 1904 the Rabbit's Foot show had expanded to fill three Pullman railroad carriages, and advertiseded as "the leading Negro show in America".[10] For the 1904-05 season, the company included week-long stands in Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland. Two of its most popular performers were singing comedian Charles "Cuba" Santana and trombonist Amos Gilliard.[4] Another performer, William Rainey, brought his young bride Gertrude (later known as "Ma" Rainey) to join the company in 1906.[4] That year, Chappelle launched a second traveling tent company, the Funny Folks Comedy Company, with performers alternating between the two companies. The business continued to expand, though in August 1908, one of the Pullman Company railroad carriages used by the show burned to the ground in Shelby, North Carolina, while several of the entertainers were asleep. Chappelle quickly ordered a new carriage and eighty-foot round tent so the show could go on the following week.[5]

Pat Chappelle died from an unspecified illness in October 1911, aged 42, and the Rabbit's Foot Company was bought in 1912 by Fred Swift Wolcott (1882-1967), a white farmer originally from Michigan, who had owned a small carnival company, F. S. Wolcott Carnivals. Wolcott maintained the Rabbit's Foot company as a touring show,[11] initially as both owner and manager, and attracted new talent including blues singer Ida Cox who joined the company in 1913. "Ma" Rainey also brought the young Bessie Smith into the troupe, and worked with her until Smith left in 1915. The show's touring base moved to Wolcott's 1,000-acre Glen Sade Plantation outside Port Gibson, Mississippi in 1918, with offices in the center of town. Wolcott began to refer to the show as a "minstrel show" – a term Chappelle had eschewed – though one member of his company, trombonist Leon "Pee Wee" Whittaker, described him as "a good man" who looked after his performers.[4] Each spring, musicians from around the country assembled in Port Gibson to create a musical, comedy, and variety show to perform under canvas. In his book The Story of the Blues, Paul Oliver wrote:[12]

The 'Foots' traveled in two cars and had an 80' x 110' tent which was raised by the roustabouts and canvassmen, while a brass band would parade in town to advertise the coming of the show...The stage would be of boards on a folding frame and Coleman lanterns – gasoline mantle lamps – acted as footlights. There were no microphones; the weaker voiced singers used a megaphone, but most of the featured women blues singers scorned such aids to volume...

The company, by this time known as "F. S. Wolcott's Original Rabbit's Foot Company" or "F. S. Wolcott’s Original Rabbit's Foot Minstrels", continued to perform its annual tours through the 1920s and 1930s, playing small towns during the week and bigger cities at weekends. The show provided a basis for the careers of many leading African American musicians and entertainers, including Butterbeans and Susie, Tim Moore, Big Joe Williams, Louis Jordan, George Guesnon, Leon "Pee Wee" Whittaker, Brownie McGhee, and Rufus Thomas. Wolcott remained its general manager and owner until he sold the company in 1950, to Earl Hendren of Erwin, Tennessee, who in turn sold it in 1955 to Eddie Moran of Monroe, Louisiana, when it was still trading under Wolcott's name.[4] Records suggest that its last performance was in 1959.[13]

Dance

As vaudeville become more popular the competition for “the most flashy” act increased. As minstrelsy became less popular other types of movement were created and carried on to the Vaudeville stage. A performer named Benjamin Franklin had an act that was described by his minstrel troupe leader, “waltzes with a pail of water on his head and plays the French horn at the same time.”[14]

Dance was an entertainment piece that was accepted in almost every act slot on the bill for a Vaudeville show. Tap, a term coined with the Ziegfeld Follies in 1902, was a style that was often seen. It started with slaves before the Civil War mimicking and mocking their white master's stiff movements. During that same time hamboning was invented. Without drums, hamboning was a way for performers to create percussion sounding beats by tapping or slapping their chests and thighs. In the 1870s and 1880s hamboning was mixed with clog-shoe dances and Irish jigs to create tap. Vaudeville had seen two types of tap: buck-and-wing and four-four time soft shoe. Buck-and-wing consisted of gliding, sliding, and stomping movements at high speeds. Wing was a portion in which on a jump, feet would continue to dance in mid air. Soft shoe was more relaxed and elegant. Metal plates were added to the bottom of tap shoes to create a stronger percussion sound. However, after just a few short dance routines the softwood Vaudeville stage would easily tatter. Theater owners replaced the section of the stage that was in front of the curtain with durable maple, which spared them from changing out the entire stage while allowing them to feature “in-one-number” acts performed with the curtain as a backdrop while the set was changed for the following act. This kept audiences entertained - and, importantly, put. Famous tapdancers of the time and who are still well-remembered today include Buster Brown and the Speed Kings, Beige & Brown, and Bill "Bojangles" Robinson.[6]

Music

The black musicians and composers of the vaudeville era influenced what is now known as American musical comedy, jazz and Broadway musical theater. The popular music of the time was ragtime, a lively form developed from black folk music prominently featuring piano and banjo.[15] The fast tempo of Ragtime matched the pace of the Vaudevillian revue type show. Thomas Greene Bethune or (“Blind Tom”) composed 100 pieces and could play over 7,000. He was exploited by a slave owner John Benthune. For example, John let Tom perform to make himself money. “Blind Tom” made $100,000 in 1866 and only received $3,000 of this. John William Boone was a fellow blind pianist, a professional at the age of fourteen, known as “Blind Boone”. John and Tom shared a piano ragtime style of “jig piano”. This consisted of the left hand playing the beat of the tuba while the right hand played the fiddle and banjo melodies. This music portrayed slaves dances, including beats at times created by the only instrument they had, their bodies.[16]

Chitlin' circuits

As the live entertainment industry grew, actors, singers, comedians, musicians, dancers, and acrobats began to retain agents to book their acts.[6] Booking associations sprung up, serving a middle man role between agents and theater owners. The dominant one of the day was the Theater Owners Booking Association (TOBA), known among colored performers of the time as “Tough On Black Actors”.[17] Its unequal treatment of performers resulted in the informal creation of "chitlin' circuits" for black entertainers. The name stemmed from a regional South dish associated with blacks and their slave heritage, “chitlins”, deep fried pig's knuckles and intestines.

Chitlin' circuit touring groups would often be forced to perform in venues such as school auditoriums because theaters were not always available to them due to segregation. ”[17] They would also travel directly to black neighborhoods to bring them entertainment. The content of the touring shows was melodramatic and farcical, designed to be enjoyed in the moment.[17]

References

- Henry T. Sampson, Blacks in Blackface: A Sourcebook on Early Black Musical Shows, Scarecrow Press, 1980 (2013 edn.), pp.48-49.

- Bernard L. Peterson, The African American Theatre Directory, 1816-1960: A Comprehensive Guide to Early Black Theatre Organizations, Companies, Theatres, and Performing Groups, Greenwood Publishing Group, 1997, p.104.

- Bernard L. Peterson, Profiles of African American Stage Performers and Theatre People, 1816-1960, Greenwood Publishing Group, 2001, p.51.

- Lynn Abbott, Doug Seroff, Ragged But Right: Black Traveling Shows, Coon Songs, and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz, Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2009, pp.248-268

- Peter Dunbaugh Smith, Ashley Street Blues: Racial Uplift and the Commodification of Vernacular Performance in LaVilla Florida, 1896-1916 Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine, Florida State University, The College of Arts and Science, Dissertation, 2006.

- Pollak, Max M. “A Short History of Tap: From Picks and Chitlins all the way to ‘Bring in ’Da Noise’.” Ballett International, Tanz akuell. 7 (2001-07): 25-27. Seelze. UCSB Main Library. October 25, 2011.

- Brown, Canter, Jr, and Larry Eugene Rivers. "'The Art of Gathering a Crowd': Florida's Pat Chappelle and the origins of Black-Owned Vaudeville", The Journal of African American History 92.2 (2007): 169+. Academic OneFile. Web. 26 October 2011.

- "Rabbit's Foot Comedy Company; T. G. Williams; William Mosely; Ross Jackson; Sam Catlett; Mr. Chappelle" News/Opinion, The Freeman page 6. October 7, 1905. Indianapolis, Indiana.

- "The Stage." News/Opinion, The Freeman, page 5. June 9, 1900. Indianapolis, Indiana.

- "Wait For The Big Show". The Afro American. 23 April 1904. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- "Notes: Rabbit Foot Company". The Freeman. 26 April 1913. Retrieved 23 November 2010.

- Paul Oliver, The Story of the Blues, 1972, ISBN 0-14-003509-5

- "Rabbit Foot Minstrels". Msbluestrail.org. Retrieved 2008-05-28.

- Emery, Lynne Fauley. Black Dance from 1619 to Today, London: Dance Books Ltd, 1988. Print.

- Blesh, Rudi; Janis, Harriet. They all Played Ragtime: The True Story of American Music. London and Beccles, Great Britain: William Clowes and Sons Ltd, 1958.

- Taylor, Fredrick J. “Black Music and Musicians in the Nineteenth Century.” The Western Journal of Black Studies. 29.3 (2005), p. 165. Academic OneFile. Web. 26 October 2011.

- Gates, Henry Louis Jr. “The Chitlin Circuit.” African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader, Oxford University Press, Inc.