Mucormycosis

Mucormycosis, also known as black fungus,[3][4] is a serious fungal infection that comes under fulminant fungal sinusitis,[11] usually in people who are immunocompromised.[9][12] It is curable only when diagnosed early.[11] Symptoms depend on where in the body the infection occurs.[13][14] It most commonly infects the nose, sinuses, eyes and brain resulting in a runny nose, one-sided facial swelling and pain, headache, fever, blurred vision, bulging or displacement of the eye (proptosis), and tissue death.[1][6] Other forms of disease may infect the lungs, stomach and intestines, and skin.[6]

It is spread by spores of molds of the order Mucorales, most often through inhalation, contaminated food, or contamination of open wounds.[15] These fungi are common in soils, decomposing organic matter (such as rotting fruit and vegetables), and animal manure, but usually do not affect people.[16] It is not transmitted between people.[14] Risk factors include diabetes with persistently high blood sugar levels or diabetic ketoacidosis, low white blood cells, cancer, organ transplant, iron overload, kidney problems, long-term steroids or use of immunosuppressants, and to a lesser extent in HIV/AIDS.[7][9]

Diagnosis is by biopsy and culture, with medical imaging to help determine the extent of disease.[5] It may appear similar to aspergillosis.[17] Treatment is generally with amphotericin B and surgical debridement.[8] Preventive measures include wearing a face mask in dusty areas, avoiding contact with water-damaged buildings, and protecting the skin from exposure to soil such as when gardening or certain outdoor work.[10] It tends to progress rapidly and is fatal in about half of sinus cases and almost all cases of the widespread type.[2][18]

Mucormycosis is usually rare, affecting fewer than 2 people per million people each year in San Francisco,[8] but is now ~80 times more common in India.[19] People of any age may be affected, including premature infants.[8] The first known case of mucormycosis was possibly the one described by Friedrich Küchenmeister in 1855.[1] The disease has been reported in natural disasters; 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2011 Joplin tornado.[20] During the COVID-19 pandemic, an association between mucormycosis and COVID-19 has been reported. This association is thought to relate to reduced immune function during the course of the illness and may also be related to glucocorticoid therapy for COVID-19.[4][21] A rise in cases was particularly noted in India.[22]

Classification

Generally, mucormycosis is classified into five main types according to the part of the body affected.[14][23] A sixth type has been described as mucormycosis of the kidney,[1] or miscellaneous, i.e., mucormycosis at other sites, although less commonly affected.[23]

- Sinuses and brain (rhinocerebral); most common in people with poorly controlled diabetes and in people who have had a kidney transplant.[14]

- Lungs (pulmonary); the most common type of mucormycosis in people with cancer and in people who have had an organ transplant or a stem cell transplant.[14]

- Stomach and intestine (gastrointestinal); more common among young, premature, and low birth weight infants, who have had antibiotics, surgery, or medications that lower the body's ability to fight infection.[14]

- Skin (cutaneous); after a burn, or other skin injury, in people with leukaemia, poorly controlled diabetes, graft-versus-host disease, HIV and intravenous drug use.[5][14]

- Widespread (disseminated); when the infection spreads to other organs via the blood.[14]

Signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of mucormycosis depend on the location in the body of the infection.[6] Infection usually begins in the mouth or nose and enters the central nervous system via the eyes.[5]

If the fungal infection begins in the nose or sinus and extends to brain, symptoms and signs may include one-sided eye pain or headache, and may be accompanied by pain in the face, numbness, fever, loss of smell, a blocked nose or runny nose. The person may appear to have sinusitis.[24] The face may look swollen on one side, with rapidly progressing "black lesions" across the nose or upper inside of mouth. One eye may look swollen and bulging, and vision may be blurred.[6][24][25]

Fever, cough, chest pain, and difficulty breathing, or coughing up blood, can occur when the lungs are involved.[6] A stomach ache, nausea, vomiting and bleeding can occur when the gastrointestinal tract is involved.[6][26] Affected skin may appear as a dusky reddish tender patch with a darkening centre due to tissue death.[12] There may be an ulcer, and it can be very painful.[5][7][12]

Invasion of the blood vessels can result in thrombosis and subsequent death of surrounding tissue due to a loss of blood supply.[7] Widespread (disseminated) mucormycosis typically occurs in people who are already sick from other medical conditions, so it can be difficult to know which symptoms are related to mucormycosis. People with disseminated infection in the brain can develop changes in mental status or lapse into a coma.[27][28]

Cause

Mucormycosis is a fungal infection caused by fungi in the order Mucorales.[5] In most cases it is due to an invasion of the genera Rhizopus and Mucor, common bread molds.[29] Most fatal infections are caused by Rhizopus oryzae.[17] It is less likely due to Lichtheimia, and rarely due to Apophysomyces.[30] Others include Cunninghamella, Mortierella, and Saksenaea.[5][31]

The fungal spores are present in the environment, can be found on items such as moldy bread and fruit, and are breathed in frequently, but cause disease only in some people.[5] In addition to being breathed in and deposited in the nose, sinuses, and lungs, the spores can also enter the skin via blood or directly through a cut or open wound, and can also grow in the intestine if eaten.[14][31] Once deposited, the fungus grows branch-like filaments which invade blood vessels, causing clots to form and surrounding tissues to die.[5] Other reported causes include contaminated wound dressings.[5] Mucormycosis has been reported following the use of elastoplast and the use of tongue depressors for holding in place intravenous catheters.[5] Outbreaks have also been linked to hospital bed sheets, negative-pressure rooms, water leaks, poor ventilation, contaminated medical equipment, and building works.[32] One hypothesis suggests that the spread of fungal spores in India could be due to fumes generated from the burning of Mucorales-rich biomass, like cow dung and crop stubble.[33]

Risk factors

Predisposing factors for mucormycosis include immune deficiencies, a low neutrophil count, and metabolic acidosis.[12][9] Risk factors include poorly controlled diabetes mellitus (particularly DKA), organ transplant, iron overload, such cancers as lymphomas, kidney failure, liver disease, severe malnutrition, and long term corticosteroid and immunosuppressive therapy.[31][10] Other risk factors include tuberculosis (TB),[20] deferoxamine[1] and to a lesser extent HIV/AIDS.[1][7] Cases of mucormycosis in fit and healthy people are less common.[7]

Corticosteroids are commonly used in the treatment of COVID-19 and reduce damage caused by the body's own immune response to the virus. They are immunosuppressant and increase blood sugar levels in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. It is thought that both these effects may contribute to cases of mucormycosis.[34][35][21]

Mechanism

Most people are frequently exposed to Mucorales without developing the disease.[31] Mucormycosis is generally spread by breathing in, eating food contaminated by, or getting spores of molds of the Mucorales type in an open wound.[15] It is not transmitted between people.[14]

The precise mechanism by which diabetics become susceptible is unclear. In vivo, a high sugar level alone does not permit the growth of the fungus, but acidosis alone does.[1][7] People with high sugar levels frequently have high iron levels, also known to be a risk factor for developing mucormycosis.[7] In people taking deferoxamine, the iron removed is captured by siderophores on Rhizopus species, which then use the iron to grow.[36]

Diagnosis

There is no blood test that can confirm the diagnosis.[37] Diagnosis requires identifying the mold in the affected tissue by biopsy and confirming it with a fungal culture.[8] Because the causative fungi occur all around and may therefore contaminate cultures underway, a culture alone is not decisive.[5] Tests may also include culture and direct detection of the fungus in lung fluid, blood, serum, plasma and urine.[20] Blood tests include a complete blood count to look specifically for neutropenia.[37] Other blood tests include iron levels, blood glucose, bicarbonate, and electrolytes.[37] Endoscopic examination of the nasal passages may be needed.[37]

Imaging

Imaging is often performed, such as CT scan of lungs and sinuses.[38] Signs on chest CT scans, such as nodules, cavities, halo signs, pleural effusion and wedge-shaped shadows, showing invasion of blood vessels, may suggest a fungal infection, but do not confirm mucormycosis.[17] A reverse halo sign in a person with a blood cancer and low neutrophil count is highly suggestive of mucormycosis.[17] CT scan images of mucormycosis can be useful to distinguish mucormycosis of the orbit and cellulitis of the orbit, but images may appear identical to those of aspergillosis.[17] MRI may also be useful.[39] Currently, MRI with gadolinium contrast is the investigation of choice in rhinoorbito-cerebral mucormycosis.

Culture and biopsy

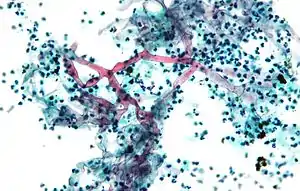

To confirm the diagnosis, biopsy samples can be cultured.[13][37] Culture from biopsy samples does not always give a result as the organism is very fragile.[17] Microscopy can usually determine the genus and sometimes the species, but may require an expert mycologist.[17] The appearance of the fungus under the microscope can vary but generally shows wide (10–20 micron), ribbon-like filaments that generally do not have septa and that—unlike in aspergillosis—branch at right angles, resembling antlers of a moose, which may be seen to be invading blood vessels.[12][37]

Ribbon-like hyphae which branch at 90°

Ribbon-like hyphae which branch at 90°.jpg.webp) Hyphae in blood vessel

Hyphae in blood vessel Mature sporangium of a Mucor[40]

Mature sporangium of a Mucor[40]

Other

Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization may be used to identify the species.[37] A blood sample from an artery may be useful to assess for metabolic acidosis.[37]

Differential diagnosis

Other filamentous fungi may however look similar.[32] It may be difficult to differentiate from aspergillosis.[41] Other possible diagnoses include anthrax, cellulitis, bowel obstruction, ecthyma gangrenosum, lung cancer, clot in lungs, sinusitis, tuberculosis and fusariosis.[42]

Prevention

Preventive measures include wearing a face mask in dusty areas, washing hands, avoiding direct contact with water-damaged buildings, and protecting skin, feet, and hands where there is exposure to soil or manure, such as gardening or certain outdoor work.[10] In high risk groups, such as organ transplant patients, antifungal drugs may be given as a preventative.[10]

Treatment

Treatment involves a combination of antifungal drugs, surgically removing infecting tissue and correcting underlying medical problems, such as diabetic ketoacidosis.[1]

Medication

Once mucormycosis is suspected, amphotericin B at an initial dose of 1 mg is initially given slowly over 10–15 minutes into a vein, then given as a once daily dose according to body weight for the next 14 days.[43] It may need to be continued for longer.[41] Isavuconazole and Posaconazole are alternatives.[20][44]

Surgery

Surgery can be very drastic, and, in some cases of disease involving the nasal cavity and the brain, removal of infected brain tissue may be required. Removal of the palate, nasal cavity, or eye structures can be very disfiguring.[26] Sometimes more than one operation is required.[31]

Other considerations

The disease must be monitored carefully for any signs of reemergence.[31][45] Treatment also requires correcting sugar levels and improving neutrophil counts.[1][7] Hyperbaric oxygen may be considered as an adjunctive therapy, because higher oxygen pressure increases the ability of neutrophils to kill the fungus.[7] The efficacy of this therapy is uncertain.[32]

Prognosis

It tends to progress rapidly and is fatal in about half of sinus cases, two thirds of lung cases, and almost all cases of the widespread type.[18] Skin involvement carries the lowest mortality rate of around 15%.[31] Possible complications of mucormycosis include the partial loss of neurological function, blindness, and clotting of blood vessels in the brain or lung.[26]

As treatment usually requires extensive and often disfiguring facial surgery, the effect on life after surviving, particularly sinus and brain involvement, is significant.[31]

Epidemiology

The true incidence and prevalence of mucormycosis may be higher than appears.[36] Mucormycosis is rare, affecting fewer than 1.7 people per million population each year in San Francisco.[8][46] It is around 80 times more prevalent in India, where it is estimated that there are around 0.14 cases per 1000 population,[19] and where its incidence has been rising.[47] Causative fungi are highly dependent on location. Apophysomyces variabilis has its highest prevalence in Asia and Lichtheimia spp. in Europe.[20] It is the third most common serious fungal infection to infect people, after aspergillosis and candidiasis.[48]

Diabetes is the main underlying disease in low and middle-income countries, whereas, blood cancers and organ transplantation are the more common underlying problems in developed countries.[19] As new immunomodulating drugs and diagnostic tests are developed, the statistics for mucormycosis have been changing.[19] In addition, the figures change as new genera and species are identified, and new risk factors reported such as tuberculosis and kidney problems.[19]

COVID-19–associated mucormycosis

_cases.png.webp)

During the COVID-19 pandemic in India, the Indian government reported that more than 11,700 people were receiving care for mucormycosis as of 25 May 2021. Many Indian media outlets called it "black fungus" because of the black discoloration of dead and dying tissue the fungus causes. Even before the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of mucormycosis in India were estimated to be about 70 times higher than in the rest of the world.[3][49] Due to its rapidly growing number of cases some Indian state governments have declared it an epidemic.[50] One treatment was a daily injection for eight weeks of anti-fungal intravenous injection of amphotericin B which was in short supply. The injection could be standard amphotericin B deoxycholate or the liposomal form. The liposomal form cost more but it was considered "safer, more effective and [with] lesser side effects".§[51] The major obstacle of using antifungal drugs in black fungus is the lack of clinical trials.[28]

Recurrence of mucormycosis during COVID-19 second wave in India

Pre-COVID mucormycosis was a very rare infection, even in India. It is so rare that an ENT (ear, nose, throat) doctor would not witness often a case during their university time. So, the documentation available on the treatment of mucormycosis is limited. In fact, there used to be a couple of mucormycosis expert ENT surgeons for millions of people pre-pandemic. The sudden rise in mucormycosis cases has left a majority of the ENT doctors with no option but to accept mucormycosis cases, as the expert doctors were very much occupied and the patient would die if left untreated. The majority of the ENT doctors had to manage with minimal or no experience on mucormycosis, this has led to the recurrence of mucormycosis in the patients they treated. When a highly experienced doctor in mucormycosis treats a patient even he cannot guarantee that the individual is completely cured and will not have a relapse of mucormycosis; an inexperienced ENT surgeon will definitely have a high number of patients with recurrence due to which there were many recurrent cases of mucormycosis although it did not get the limelight of media or the Indian Government.[52]

History

The first case of mucormycosis was possibly one described by Friedrich Küchenmeister in 1855.[1] Fürbringer first described the disease in the lungs in 1876.[53] In 1884, Lichtheim established the development of the disease in rabbits and described two species; Mucor corymbifera and Mucor rhizopodiformis, later known as Lichtheimia and Rhizopus, respectively.[1] In 1943, its association with poorly controlled diabetes was reported in three cases with severe sinus, brain and eye involvement.[1]

In 1953, Saksenaea vasiformis, found to cause several cases, was isolated from Indian forest soil, and in 1979, P. C. Misra examined soil from an Indian mango orchard, from where they isolated Apophysomyces, later found to be a major cause of mucormycosis.[1] Several species of mucorales have since been described.[1] When cases were reported in the United States in the mid-1950s, the author thought it to be a new disease resulting from the use of antibiotics, ACTH and steroids.[53][54] Until the latter half of the 20th century, the only available treatment was potassium iodide. In a review of cases involving the lungs diagnosed following flexible bronchoscopy between 1970 and 2000, survival was found to be better in those who received combined surgery and medical treatment, mostly with amphotericin B.[53]

Naming

Arnold Paltauf coined the term "Mycosis Mucorina" in 1885, after describing a case with systemic symptoms involving the sinus, brain and gastrointestinal tract, following which the term "mucormycosis" became popular.[1] "Mucormycosis" is often used interchangeably with "zygomycosis", a term made obsolete following changes in classification of the kingdom Fungi. The former phylum Zygomycota included Mucorales, Entomophthorales, and others. Mucormycosis describes infections caused by fungi of the order Mucorales.[41]

COVID-19–associated mucormycosis

COVID-19 associated mucormycosis cases were reported during first and second(delta) wave, with maximum number of cases in delta wave.[11] There were no cases reported during the Omicron wave.[11] A number of cases of mucormycosis, aspergillosis, and candidiasis, linked to immunosuppressive treatment for COVID-19 were reported during the COVID-19 pandemic in India in 2020 and 2021.[4][39] One review in early 2021 relating to the association of mucormycosis and COVID-19 reported eight cases of mucormycosis; three from the U.S., two from India, and one case each from Brazil, Italy, and the UK.[21] The most common underlying medical condition was diabetes.[21] Most had been in hospital with severe breathing problems due to COVID-19, had recovered, and developed mucormycosis 10–14 days following treatment for COVID-19. Five had abnormal kidney function tests, three involved the sinus, eye and brain, three the lungs, one the gastrointestinal tract, and in one the disease was widespread.[21] In two of the seven deaths, the diagnosis of mucormycosis was made at postmortem.[21] That three had no traditional risk factors led the authors to question the use of steroids and immunosuppressive drugs.[21] Although, there were cases without diabetes or use of immunosuppressive drugs. There were cases reported even in children.[11] In May 2021, the BBC reported increased cases in India.[34] In a review of COVID-19-related eye problems, mucormycosis affecting the eyes was reported to occur up to several weeks following recovery from COVID-19.[39] It was observed that people with COVID-19 were recovering from mucormycosis a bit easily when compared to non-COVID-19 patients. This is because unlike non-COVID-19 patients with severe diabetes, cancer or HIV, the recovery time required for the main cause of immune suppression is temporary.[11]

Other countries affected included Pakistan,[55] Nepal,[56] Bangladesh,[57] Russia,[58] Uruguay,[59] Paraguay,[60] Chile,[61] Egypt,[62] Iran,[63] Brazil,[64] Iraq,[65] Mexico,[66] Honduras,[67] Argentina[68] Oman,[69] and Afghanistan.[70] One explanation for why the association has surfaced remarkably in India is high rates of COVID-19 infection and high rates of diabetes.[71] In May 2021, the Indian Council of Medical Research issued guidelines for recognising and treating COVID-19–associated mucormycosis.[72] In India, as of 28 June 2021, over 40,845 people have been confirmed to have mucormycosis, and 3,129 have died. From these cases, 85.5% (34,940) had a history of being infected with SARS-CoV-2 and 52.69% (21,523) were on steroids, also 64.11% (26,187) had diabetes.[73][74]

Society and culture

The disease has been reported in natural disasters and catastrophes; 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami and the 2011 Missouri tornado.[20][75] The first international congress on mucormycosis was held in Chicago in 2010, set up by the Hank Schueuler 41 & 9 Foundation, which was established in 2008 for the research of children with leukaemia and fungal infections.[1] A cluster of infections occurred in the wake of the 2011 Joplin tornado. By July 19, 2011, a total of 18 suspected cases of mucormycosis of the skin had been identified, of which 13 were confirmed. A confirmed case was defined as 1) necrotizing soft-tissue infection requiring antifungal treatment or surgical debridement in a person injured in the tornado, 2) with illness onset on or after May 22 and 3) positive fungal culture or histopathology and genetic sequencing consistent with a mucormycete. No additional cases related to that outbreak were reported after June 17. Ten people required admission to an intensive-care unit, and five died.[76][77]

In 2014, details of a lethal mucormycosis outbreak that occurred in 2008 emerged after television and newspaper reports responded to an article in a pediatric medical journal.[78][79] Contaminated hospital linen was found to be spreading the infection. A 2018 study found many freshly laundered hospital linens delivered to U.S. transplant hospitals were contaminated with Mucorales.[80] Another study attributed an outbreak of hospital-acquired mucormycosis to a laundry facility supplying linens contaminated with Mucorales. The outbreak stopped when major changes were made at the laundry facility. The authors raised concerns on the regulation of healthcare linens.[81]

Other animals

Mucormycosis in other animals is similar, in terms of frequency and types, to that in people.[82] Cases have been described in cats, dogs, cows, horses, dolphins, bison, and seals.[82]

Further reading

- Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SC, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, et al. (December 2019). "Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 19 (12): e405–e421. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30312-3. PMC 8559573. PMID 31699664.

External links

- Chander J (2018). "26. Mucormycosis". Textbook of Medical Mycology (4th ed.). New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Ltd. pp. 534–596. ISBN 978-93-86261-83-0.

- "Orphanet: Zygomycosis". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on May 13, 2021. Retrieved May 13, 2021.

- Dyer O (May 2021). "Covid-19: India sees record deaths as "black fungus" spreads fear". BMJ. 373: n1238. doi:10.1136/bmj.n1238. PMID 33985993.

- Quarterly Current Affairs Vol. 4 - October to December 2020 for Competitive Exams. Vol. 4. Disha Publications. 2020. p. 173. ISBN 978-93-90486-29-8.

- Grossman ME, Fox LP, Kovarik C, Rosenbach M (2012). "1. Subcutaneous and deep mycoses: Zygomucosis/Mucormycosis". Cutaneous Manifestations of Infection in the Immunocompromised Host (2nd ed.). Springer. pp. 51–58. ISBN 978-1-4419-1577-1.

- "Symptoms of Mucormycosis". www.cdc.gov. January 14, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Spellberg B, Edwards J, Ibrahim A (July 2005). "Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (3): 556–69. doi:10.1128/CMR.18.3.556-569.2005. PMC 1195964. PMID 16020690.

- "Mucormycosis". NORD (National Organization for Rare Disorders). Archived from the original on May 26, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Hernández, J. L.; Buckley, C. J. (January 2021). Mucormycosis. PMID 31335084.

- "People at Risk For Mucormycosis and prevention". www.cdc.gov. February 2, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Meghanadh KR (May 15, 2021). "Mucormycosis / Black fungus infection". Medy Blog. Retrieved June 27, 2021.

- Johnstone RB (2017). "25. Mycoses and Algal infections". Weedon's Skin Pathology Essentials (2nd ed.). Elsevier. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-7020-6830-0.

- "ICD-11 - ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics". icd.who.int. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- "About Mucormycosis". www.cdc.gov. May 25, 2021.

- Reid G, Lynch JP, Fishbein MC, Clark NM (February 2020). "Mucormycosis". Seminars in Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 41 (1): 99–114. doi:10.1055/s-0039-3401992. PMID 32000287. S2CID 210984392.

- "Where Mucormycosis Comes From". www.cdc.gov. February 1, 2021. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Thornton CR (2020). "1. Detection of the 'Big Five' mold killers of humans: Aspergillus, Fusarium, Lomentospora, Scedosporium and Mucormycetes". In Gadd GM, Sariaslani S (eds.). Advances in Applied Microbiology. Academic Press. pp. 4–22. ISBN 978-0-12-820703-1.

- "Mucormycosis Statistics | Mucormycosis | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. May 5, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Skiada A, Pavleas I, Drogari-Apiranthitou M (November 2020). "Epidemiology and Diagnosis of Mucormycosis: An Update". Journal of Fungi. 6 (4): 265. doi:10.3390/jof6040265. PMC 7711598. PMID 33147877.

- Dannaoui E, Lackner M (December 2019). "Special Issue: Mucorales and Mucormycosis". Journal of Fungi. 6 (1): 6. doi:10.3390/jof6010006. PMC 7151165. PMID 31877973.

- Garg D, Muthu V, Sehgal IS, Ramachandran R, Kaur H, Bhalla A, et al. (May 2021). "Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) Associated Mucormycosis (CAM): Case Report and Systematic Review of Literature". Mycopathologia. 186 (2): 289–298. doi:10.1007/s11046-021-00528-2. PMC 7862973. PMID 33544266.

- Singh AK, Singh R, Joshi SR, Misra A (May 2021). "Mucormycosis in COVID-19: A systematic review of cases reported worldwide and in India". Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome. 15 (4): 102146. doi:10.1016/j.dsx.2021.05.019. PMC 8137376. PMID 34192610.

- Riley TT, Muzny CA, Swiatlo E, Legendre DP (September 2016). "Breaking the Mold: A Review of Mucormycosis and Current Pharmacological Treatment Options". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 50 (9): 747–57. doi:10.1177/1060028016655425. PMID 27307416. S2CID 22454217.

- McDonald PJ. "Mucormycosis (Zygomycosis) Clinical Presentation: History and Physical Examination". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved May 28, 2021.

- Lee S (2001). BrainChip for Microbiology. Blackwell Science. p. 70. ISBN 0-632-04568-X.

- "MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia: Mucormycosis". Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP (September 2013). "Epidemiology and treatment of mucormycosis". Future Microbiology. 8 (9): 1163–75. doi:10.2217/fmb.13.78. PMID 24020743.

- Spellberg B, Edwards J, Ibrahim A (July 2005). "Novel perspectives on mucormycosis: pathophysiology, presentation, and management". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 18 (3): 556–69. doi:10.1128/cmr.18.3.556-569.2005. PMC 1195964. PMID 16020690.

- Lee SC, Idmurm A (2018). "8. Fingal sex: The Mucoromycota". In Heitman J, Howlett BJ, Crous PW, Stukenbrock EH, James TY, Gow NA (eds.). The Fungal Kingdom. Wiley. pp. 177–192. ISBN 978-1-55581-958-3.

- Martínez-Herrera E, Frías-De-León MG, Julián-Castrejón A, Cruz-Benítez L, Xicohtencatl-Cortes J, Hernández-Castro R (August 2020). "Rhino-orbital mucormycosis due to Apophysomyces ossiformis in a patient with diabetes mellitus: a case report". BMC Infectious Diseases. 20 (1): 614. doi:10.1186/s12879-020-05337-4. PMC 7437167. PMID 32811466.

- McDonald PJ (September 10, 2018). "Mucormycosis (Zygomycosis): Background, Etiology and Pathophysiology, Epidemiology". Medscape.

- "For Healthcare Professionals | Mucormycosis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. June 17, 2020. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Skaria J, John TM, Varkey S, Kontoyiannis DP (April 2022). "Are Unique Regional Factors the Missing Link in India's COVID-19-Associated Mucormycosis Crisis?". mBio. 13 (2): e0047322. doi:10.1128/mbio.00473-22. PMC 9040830. PMID 35357212.

- Biswas S (May 9, 2021). "Mucormycosis: The 'black fungus' maiming Covid patients in India". BBC News. British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved May 11, 2021.

- Koehler P, Bassetti M, Chakrabarti A, Chen SC, Colombo AL, Hoenigl M, et al. (June 2021). "Defining and managing COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis: the 2020 ECMM/ISHAM consensus criteria for research and clinical guidance". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 21 (6): e149–e162. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30847-1. PMC 7833078. PMID 33333012.

- Prakash H, Chakrabarti A (March 2019). "Global Epidemiology of Mucormycosis". Journal of Fungi. 5 (1): 26. doi:10.3390/jof5010026. PMC 6462913. PMID 30901907.

- McDonald PJ. "Mucormycosis (Zygomycosis) Workup: Approach Considerations, Laboratory Tests, Radiologic Studies". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- "Diagnosis and Testing of Mucormycosis | Mucormycosis | CDC". www.cdc.gov. January 14, 2021.

- Sen M, Honavar SG, Sharma N, Sachdev MS (March 2021). "COVID-19 and Eye: A Review of Ophthalmic Manifestations of COVID-19". Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 69 (3): 488–509. doi:10.4103/ijo.IJO_297_21. PMC 7942063. PMID 33595463.

- "Details - Public Health Image Library(PHIL)". phil.cdc.gov. Retrieved May 26, 2021.

- Cornely OA, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Arenz D, Chen SC, Dannaoui E, Hochhegger B, et al. (December 2019). "Global guideline for the diagnosis and management of mucormycosis: an initiative of the European Confederation of Medical Mycology in cooperation with the Mycoses Study Group Education and Research Consortium". The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. 19 (12): e405–e421. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30312-3. PMC 8559573. PMID 31699664. (several authors)

- McDonald PJ. "Mucormycosis (Zygomycosis) Differential Diagnoses". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- BNF (80 ed.). BMJ Group and the Pharmaceutical Press. September 2020 – March 2021. pp. 629–635. ISBN 978-0-85711-369-6.

- McDonald PJ (September 10, 2018). "What is the role of isavuconazole (Cresemba) in the treatment of mucormycosis (zygomycosis)?". www.medscape.com. Retrieved May 25, 2021.

- Rebecca J. Frey. "Mucormycosis". Health A to Z. Archived from the original on May 18, 2008. Retrieved May 19, 2008.

- "Mucormycosis Statistics | Mucormycosis | Fungal Diseases | CDC". www.cdc.gov. June 5, 2020. Archived from the original on May 21, 2021. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- Vallabhaneni S, Mody RK, Walker T, Chiller T (2016). "1. The global burden of fungal disease". In Sobel J, Ostrosky-Zeichner L (eds.). Fungal Infections, An Issue of Infectious Disease Clinics of North America. Philadelphia: Elsevier. pp. 5–12. ISBN 978-0-323-41649-8.

- Petrikkos G, Skiada A, Lortholary O, Roilides E, Walsh TJ, Kontoyiannis DP (February 2012). "Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 54 (suppl_1): S23-34. doi:10.1093/cid/cir866. PMID 22247442.

- Schwartz I, Chakrabarti A (June 2, 2021). "'Black fungus' is creating a whole other health emergency for Covid-stricken India". The Guardian. Retrieved June 3, 2021.

- Wadhawan DW, Jain P, Shrivastava S, Kunal K (May 19, 2021). "Rajasthan declares black fungus an epidemic; cases pile up in several states | 10 points". India Today. Retrieved May 20, 2021.

- "Black fungus in India: Concern over drug shortage as cases rise". BBC News. May 19, 2021. Retrieved July 8, 2021.

- "Recurrence of Mucormycosis due to partial treatments". June 22, 2021.

- Yamin HS, Alastal AY, Bakri I (January 2017). "Pulmonary Mucormycosis Over 130 Years: A Case Report and Literature Review". Turkish Thoracic Journal. 18 (1): 1–5. doi:10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2017.16033. PMC 5783164. PMID 29404149.

- Baker RD (March 1957). "Mucormycosis; a new disease?". Journal of the American Medical Association. 163 (10): 805–8. doi:10.1001/jama.1957.02970450007003. PMID 13405736.

- "'Cases of Black Fungus emerge across Pakistan'". The News International. May 12, 2021.

- "Focused COVID-19 Media Monitoring, Nepal (May 24, 2021)". ReliefWeb. May 24, 2021.

- "Bangladesh reports 1st death by black fungus". Anadolu Agency. May 25, 2021.

- "Russia Confirms Rare, Deadly 'Black Fungus' Infections Seen in India". The Moscow Times. May 17, 2021.

- "Paciente con COVID-19 se infectó con el "hongo negro"". EL PAÍS Uruguay (in Spanish). May 25, 2021.

- "Confirman dos casos de "hongo negro" en Paraguay". RDN (in Spanish). May 27, 2021.

- "Detectan primer caso de "hongo negro" en Chile en paciente con Covid-19: es el segundo reportado en Latinoamérica". El Mostrador (in Spanish). May 28, 2021.

- "Mansoura University Hospital reports black fungus cases". Egypt Independent. May 28, 2021.

- "Coronavirus in Iran: Power outages, black fungus, and warnings of a fifth surge". Track Persia. May 29, 2021. Archived from the original on May 29, 2021. Retrieved June 1, 2021.

- "Casos suspeitos de fungo preto são investigados no Brasil; entenda". Catraca Livre (in Portuguese). May 31, 2021.

- "Iraq detects five cases of the deadly "black fungus" among coronavirus patients". Globe Live Media. June 1, 2021.

- "Detectan en Edomex posible primer caso de hongo negro en México". Uno TV (in Spanish). June 3, 2021.

- "Salud confirma primer caso de hongo negro en Honduras". Diario El Heraldo (in Spanish). June 7, 2021.

- ""Hongo negro": advierten que hay que estar atentos a la coinfección fúngica en pacientes con covid". Clarín (in Spanish). June 16, 2021.

- "'Black fungus' detected in 3 COVID-19 patients in Oman". Al Jazeera. June 15, 2021.

- "Afghanistan finds deadly 'black fungus' in virus patients – latest updates". TRT World. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- Runwal P (May 14, 2021). "A rare black fungus is infecting many of India's COVID-19 patients—why?". National Geographic.

- "ICMR releases diagnosis and management guidelines for COVID-19-associated Mucormycosis". Firstpost. May 17, 2021.

- "India reports 40,854 cases of black fungus so far". Mint. June 28, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- "Delhi has more black fungus infections than active Covid-19 cases: Govt data". Mint. July 14, 2021. Retrieved July 16, 2021.

- Fanfair, Robyn Neblett; et al. (July 29, 2011). "Notes from the Field: Fatal Fungal Soft-Tissue Infections After a Tornado – Joplin, Missouri, 2011". MMWR Weekly. 60 (29): 992.

- Williams, Timothy (June 10, 2011) Rare Infection Strikes Victims of a Tornado in Missouri. New York Times.

- Neblett Fanfair R, Benedict K, Bos J, Bennett SD, Lo YC, Adebanjo T, et al. (December 2012). "Necrotizing cutaneous mucormycosis after a tornado in Joplin, Missouri, in 2011". The New England Journal of Medicine. 367 (23): 2214–25. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1204781. PMID 23215557.

- Catalanello, Rebecca (April 16, 2014). "Mother believes her newborn was the first to die from fungus at Children's Hospital in 2008". NOLA.com.

- "5 Children's Hospital patients died in 2008, 2009 after contact with deadly fungus".

We acknowledge that Children's Hospital is Hospital A in an upcoming article in The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. The safety and well-being of our patients are our top priorities, so as soon as a problem was suspected, the State Health Department and CDC were notified and invited to assist in the investigation. The hospital was extremely aggressive in trying to isolate and then eliminate the source of the fungus.

- Sundermann AJ, Clancy CJ, Pasculle AW, Liu G, Cumbie RB, Driscoll E, et al. (February 2019). "How Clean Is the Linen at My Hospital? The Mucorales on Unclean Linen Discovery Study of Large United States Transplant and Cancer Centers". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 68 (5): 850–853. doi:10.1093/cid/ciy669. PMC 6765054. PMID 30299481.

- Sundermann, Alexander J.; Clancy, Cornelius J.; Pasculle, A. William; Liu, Guojun; Cheng, Shaoji; Cumbie, Richard B.; Driscoll, Eileen; Ayres, Ashley; Donahue, Lisa; Buck, Michael; Streifel, Andrew (July 20, 2021). "Remediation of Mucorales-contaminated Healthcare Linens at a Laundry Facility Following an Investigation of a Case Cluster of Hospital-acquired Mucormycosis". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 74 (8): 1401–1407. doi:10.1093/cid/ciab638. ISSN 1537-6591. PMID 34282829.

- Seyedmousavi S, Bosco SM, de Hoog S, Ebel F, Elad D, Gomes RR, et al. (April 2018). "Fungal infections in animals: a patchwork of different situations". Medical Mycology. 56 (suppl_1): 165–187. doi:10.1093/mmy/myx104. PMC 6251577. PMID 29538732.