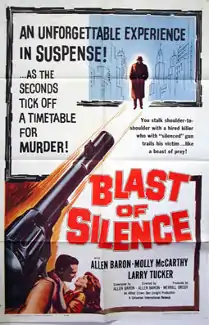

Blast of Silence

Blast of Silence is a 1961 American neo-noir written, directed by, and starring Allen Baron. The film also stars Molly McCarthy and Larry Tucker and features Peter H. Clune. It was produced by Merrill Brody, who was also the cinematographer.[3]

| Blast of Silence | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Allen Baron |

| Written by | Allen Baron Waldo Salt (narration, uncredited)[1] Will Sparks {story consultant)[2] |

| Produced by | Merrill Brody |

| Starring | Allen Baron Molly McCarthy Larry Tucker |

| Narrated by | Lionel Stander (uncredited)[1] |

| Cinematography | Merrill Brody |

| Edited by | Peggy Lawson |

| Music by | Meyer Kupferman |

| Color process | Black and white |

Production company | Magla Productions |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 77 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $20,000[1] |

Plot

Frankie Bono, an Italian-American Mafia hitman working with the Mafia in Cleveland, returns to his hometown of New York City during Christmas week to kill Troiano, a middle-management mobster. The assassination will be risky, and Frankie is warned by the go-between who delivers the front half of Frankie's money that the contract will be reneged if he is spotted before the hit is performed.

Frankie follows his target to select the best possible location, but he opts to wait until Troiano isn't being accompanied by his bodyguards. He then goes to purchase a revolver from Big Ralph, an obese man who keeps sewer rats as pets. The encounter with this old acquaintance leaves Frankie feeling disgusted. With several days left before the hit is to be performed, Frankie decides to kill time in the city, where he is plagued by memories of past trauma during his time living there.

While sitting alone for a drink, Frankie is spotted by his childhood friend Petey, who invites the reluctant Frankie to a Christmas party with Petey's sister, Lorrie, with whom Frankie was also acquainted during his early years in New York. Despite his reluctance, Frankie, who grew up as an orphan, attends the party and uneasily enjoys spending time with a family for Christmas. The following day, Frankie goes to see Lorrie at her apartment to get reacquainted with her, but the visit ends in disaster when an initially vulnerable Frankie suddenly attempts to sexually assault her. Lorrie forgives Frankie for his actions and calmly asks him to leave, and he obliges.

The same day, Frankie tails Troiano and his mistress to the Village Gate jazz club in Greenwich Village. However, he is spotted by Big Ralph, who decides to blackmail Frankie for more money for the gun. Frankie stalks Ralph back to his tenement apartment and strangles him to death following a violent fight. Losing his nerve, Frankie calls his employers to tell them he wants to quit the job. Unsympathetic, the Mafia higher-ups warn Frankie that he is in trouble for even thinking of quitting and that he has until New Year's Eve to perform the hit.

Having settled on using Troiano's mistress's apartment as the location for the hit, Frankie makes one last stop at Lorrie's home to apologize for his behavior and to convince her to leave New York with him, only to learn she has a live-in boyfriend. Frankie leaves angrily to finish the job.

After killing Troiano, Frankie narrowly evades being caught by Troiano's mistress and then calls to get the location to receive the rest of his payment. However, the meeting, set in a lonely isolated spot on the water, is an ambush, and Frankie is riddled with bullets. He falls into the water, dead.

Cast

|

|

- Sources:[2] and film credits

Production

Writer/director Allen Baron raised $2,800 to shoot and develop test footage, which then enabled him to raise an additional $180,000 to make the film; the test footage was used in the final film. The lead part was intended for Peter Falk, a friend of Baron's from summer stock theater, but Falk got a paying job in Murder, Inc., so the role fell to Baron to play, with the test footage serving as his screen test. Many of Baron's friends and family appear in the film.[1]

Twenty-two days of shooting took place over a four-month period of time ending in January 1960.[2] The majority of scenes were filmed in actual New York City locations, without a filming permit.[1] Reportedly, some interiors were shot in a studio on West Forty-Fifth Street.[2] The exterior chase that ends the film was shot at the "Old Mill" on a Jamaica Bay estuary on Long Island during Hurricane Donna (September 10–12, 1960), the only hurricane of the 20th century to blanket the entire East Coast from south Florida to Maine. The location was locally said to be a dumping ground for the dead bodies of mob hits, which is why it was selected by Baron for the scene. Its isolation also meant that a full day's shooting could take place without permits. The final shot, with the dead hit man falling into the water, was made in one take; Baron did his own stunts.[4][5]

The film was shot with equipment that had been left behind in Cuba after the shooting of Errol Flynn's final film, Cuban Rebel Girls when the crew had to flee the country due to the Cuban Revolution. Baron made a deal with that film's producers that he could use the equipment if he managed to smuggle it out of the country. Complicating the situation was that Baron, who had been a crew member on that shoot, had accidentally shot and wounded a man, and was wanted in Cuba for that crime. He had also unknowingly slept with the girlfriend of a local Cuban gangster.[5]

The narration – which was added after the film was completed, to help tie it together – was written by blacklisted writer Waldo Salt, using the name Mel Davenport, and read, uncredited, by blacklisted actor Lionel Stander. Stander was paid $500 for the work; it would have cost an additional $500 to use Stander's name in the credits.[1]

Baron and the producer, Merrill Brody, sold the rights to the film in perpetuity to Universal for a mere $50,000.[5]

Release

Blast of Silence was released in Chicago on June 5, 1961 and in New York City on December 29, 1961.[2] The film was also an entry at the Spoleto Film Festival in Spoleto, Italy, the Locarno Film Festival in Switzerland, and was an invited entry at the Cannes Film Festival.[2]

The Criterion Collection released Blast of Silence on DVD in 2008. The disc's special features include a new, restored digital transfer, a making-of featurette (Requiem for a Killer: The Making of Blast of Silence), rare on-set Polaroid photos, and images of locations as they existed in 2008. Also included is a booklet featuring an essay by film critic Terrence Rafferty and a four-page comic by Sean Phillips (Criminal, Sleeper, Marvel Zombies).

Reception

Eugene Archer of The New York Times wrote that the film was "awkward and pretentious" because it was trying to hew to American conventions of filmmaking while attempting to be "offbeat and 'arty'", but Archer praised the filming of places in New York City.[6] In Photoplay, Janet Graves wrote that the "unpretentious air" clashes with the style of the narration, described by the writer as "both fancy and too-too tough".[7]

In The New Yorker, Richard Brody wrote "many of the images deserve to be iconic."[8] J.R. Jones in Chicago Reader wrote that the film "might seem comical if it weren’t so rooted in existential dread."[9]

References

- Muller, Eddie (December 19, 2021) Intro to TCM presentation on "Noir Alley" Turner Classic Movies

- "Blast of Silence". American Film Institute. Retrieved January 21, 2018.

- Silver, Alain and Ward, Elizabeth; eds. (1992). Film Noir: An Encyclopedic Reference to the American Style (3rd ed.) Woodstock, New York: The Overlook Press ISBN 0-87951-479-5

- "Blast of Silence (1961)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved December 18, 2021.

- Muller, Eddie (December 19, 2021) Outro to TCM presentation on "Noir Alley" Turner Classic Movies

- Archer, Eugene (December 30, 1961). "Screen: 'Blast of Silence':Allen Baron Is Writer, Director and Actor". The New York Times. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- Graves, Janet (August 1961). Go Out to a Movie. pp. 12 - 16.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - Brody, Richard. "Blast of Silence". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on January 18, 2013. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

- Jones, J. R. (October 29, 2004). "Blast of Silence". Chicago Reader. Retrieved January 7, 2022.

External links

- Blast of Silence at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Blast of Silence at IMDb

- Blast of Silence at AllMovie

- Blast of Silence at the TCM Movie Database

- Blast of Silence at Rotten Tomatoes

- Joe Dante on Blast of Silence at Trailers From Hell

- Blast of Silence: Bad Trip an essay by Terrence Rafferty at the Criterion Collection