Whole blood

Whole blood (WB) is human blood from a standard blood donation.[1] It is used in the treatment of massive bleeding, in exchange transfusion, and when people donate blood to themselves.[1][2] One unit of whole blood (~517 mls) brings up hemoglobin levels by about 10 g/L.[3][4] Cross matching is typically done before the blood is given.[2][5] It is given by injection into a vein.[6]

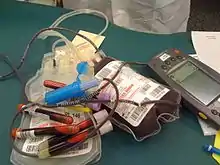

A Red Cross whole blood donation | |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | IV |

| ATC code | |

| Identifiers | |

| ChemSpider |

|

Side effects include red blood cell breakdown, high blood potassium, infection, volume overload, lung injury, and allergic reactions such as anaphylaxis.[2][3] Whole blood is made up of red blood cells, white blood cells, platelets, and blood plasma.[3] It is best within a day of collection; however, can be used for up to three weeks.[3][5][7] The blood is typically combined with an anticoagulant and preservative during the collection process.[8]

The first transfusion of whole blood was in 1818; however, common use did not begin until the First and Second World Wars.[5][9] It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[10][11] In the 1980s the cost of whole blood was about US$50 per unit in the United States.[12] Whole blood is not commonly used outside of the developing world and military.[2] It is used to make a number of blood products including packed red blood cells, platelet concentrate, cryoprecipitate, and fresh frozen plasma.[1]

Medical use

Whole blood has similar risks to a transfusion of red blood cells and must be cross-matched to avoid hemolytic transfusion reactions. Most of the reasons for use are the same as those for RBCs, and whole blood is not frequently used in high income countries where packed red blood cells are readily available.[13][14] However, use of whole blood is much more common in low and middle income countries. Over 40% of blood collected in low-income countries is administered as whole blood, and approximately a third of all blood collected in middle-income countries is administered as whole blood.[15]

Whole blood is sometimes "recreated" from stored red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) for neonatal transfusions. This is done to provide a final product with a very specific hematocrit (percentage of red cells) with type O red cells and type AB plasma to minimize the chance of complications.

Transfusion of whole blood is being used in the military setting and is being studied in pre-hospital trauma care and in the setting of massive transfusion in the civilian setting.[13][16][17][14]

Processing

Historically, blood was transfused as whole blood without further processing. Most blood banks now split the whole blood into two or more components,[18] typically red blood cells and a plasma component such as fresh frozen plasma. Platelets for transfusion can also be prepared from a unit of whole blood. Some blood banks have replaced this with platelets collected by plateletpheresis because whole blood platelets, sometimes called "random donor" platelets, must be pooled from multiple donors to get enough for an adult therapeutic dose.

The collected blood is generally separated into components by one of three methods. A centrifuge can be used in a "hard spin" which separates whole blood into plasma and red cells or a "soft spin" which separates it into plasma, buffy coat (used to make platelets), and red blood cells. The third method is sedimentation: the blood simply sits overnight and the red cells and plasma are separated by gravitational interactions.

Storage

Whole blood is typically stored under the same conditions as red blood cells and can be kept up to 35 days if collected with CPDA-1 storage solution or 21 days with other common storage solutions such as CPD.

If the blood is used to make platelets, it is kept at room temperature until the process is complete. This must be done quickly to minimize the warm storage of RBCs in the unit.

References

- Hess JR, Beyer GM (2007). "Red Blood Cell Metabolism During Storage: Basic Principles and Practical Aspects". In Hillyer CD (ed.). Blood Banking and Transfusion Medicine: Basic Principles & Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 190. ISBN 978-0443069819. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12.

- Connell NT (December 2016). "Transfusion Medicine". Primary Care. 43 (4): 651–659. doi:10.1016/j.pop.2016.07.004. PMID 27866583.

- Plumer AL (2007). "Transfusion Therapy". Plumer's Principles and Practice of Intravenous Therapy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 422. ISBN 9780781759441. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12.

- Woodson LC, Sherwood ER, Kinsky MP, Talon M, Martinello C, Woodson SM (2012). "Anesthesia for burned patients". In Herndon DN (ed.). Total Burn Care: Expert Consult - Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 194. ISBN 9781455737970.

- Bahr MP, Yazer MH, Triulzi DJ, Collins RA (December 2016). "Whole blood for the acutely haemorrhaging civilian trauma patient: a novel idea or rediscovery?". Transfusion Medicine. 26 (6): 406–414. doi:10.1111/tme.12329. PMID 27357229. S2CID 24552025.

- Flagg C (2015). "Intravenous Therapy". In Linton AD (ed.). Introduction to Medical-Surgical Nursing. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 287. ISBN 9781455776412. Archived from the original on 2017-09-14.

- Marini JF, Wheeler AP (2012). "Blood Conservation and Transfusion". Critical Care Medicine: The Essentials (4th ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 267. ISBN 9781451152845. Archived from the original on 2017-01-11.

- Rudmann SV, ed. (2005). "Donor Screening and Blood Collection". Textbook of Blood Banking and Transfusion Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 205. ISBN 072160384X. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12.

- Tanaka K (2012). "Transfusion and Coagulation Therapy". In Hemmings HC, Egan TD (eds.). Pharmacology and Physiology for Anesthesia: Foundations and Clinical Application. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 628. ISBN 978-1455737932. Archived from the original on 2017-01-11.

- World Health Organization (2019). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/325771. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- World Health Organization (2021). World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/345533. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- "Introduction and Summary". Blood policy & technology. DIANE Publishing. 1985. p. 8. ISBN 9781428923331. Archived from the original on 2017-01-12.

- Flint AW, McQuilten ZK, Wood EM (April 2018). "Massive transfusions for critical bleeding: is everything old new again?". Transfusion Medicine. 28 (2): 140–149. doi:10.1111/tme.12524. PMID 29607593. S2CID 4561424.

- Pivalizza EG, Stephens CT, Sridhar S, Gumbert SD, Rossmann S, Bertholf MF, et al. (July 2018). "Whole Blood for Resuscitation in Adult Civilian Trauma in 2017: A Narrative Review". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 127 (1): 157–162. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000003427. PMID 29771715. S2CID 21697290.

- "Blood safety and availability". www.who.int. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

- "Blood Far Forward". THOR. Retrieved 2019-06-22.

- Goforth CW, Tranberg JW, Boyer P, Silvestri PJ (June 2016). "Fresh Whole Blood Transfusion: Military and Civilian Implications". Critical Care Nurse. 36 (3): 50–57. doi:10.4037/ccn2016780. PMID 27252101.

- Greene CE, Hillyer CD (17 June 2009). "Component preparation and manufacturing". In Hillyer CD, Shaz BH, Zimring JC, Abshire TC (eds.). Transfusion Medicine and Hemostasis: Clinical and Laboratory Aspects. Elsevier. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-0-12-374432-6. Archived from the original on 23 September 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2010.

External links

- Blood & Blood Products from U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)