Bloodhound LSR

Bloodhound LSR, formerly Bloodhound SSC, is a British land vehicle designed to travel at supersonic speeds with the intention of setting a new world land speed record.[1] The arrow-shaped car, under development since 2008, is powered by a jet engine and will be fitted with an additional rocket engine.[2] The initial goal is to exceed the current speed record of 763 mph (1,228 km/h), with the vehicle believed to be able to achieve up to 1,000 miles per hour (1,609 km/h).[3][4][5]

| Bloodhound LSR | |

|---|---|

| |

| Overview | |

| Manufacturer | Grafton LSR Ltd, Bristol |

| Assembly | UK Land Speed Record Centre, Berkeley, Gloucestershire, England |

| Body and chassis | |

| Class | Land speed record vehicle |

| Powertrain | |

| Engine | Rolls-Royce Eurojet EJ200 afterburning turbofan |

| Dimensions | |

| Wheelbase | 8.9 m (29 ft) |

| Length | 12.9 m (42 ft) |

| Width | 2.5 m (8.2 ft) |

| Height | 3.0 m (9.8 ft) |

| Kerb weight | 6,422 kg (14,158 lb) fuelled |

| Chronology | |

| Predecessor | ThrustSSC |

Driver Andy Green will attempt to break his own record, set in 1997. The previous business behind Project Bloodhound went into administration (bankruptcy) in late 2018. Entrepreneur Ian Warhurst bought the car to keep the project alive. A new company called Grafton LSR Ltd was formed to manage the project, which was renamed Bloodhound LSR and moved to SGS Berkeley Green University Technical College. Lack of funds and the COVID-19 pandemic stalled progress in 2020, and in 2021 the vehicle was offered for sale.

The venue for high speed testing and future world land speed record attempts is the Hakskeen Pan in the Mier area of the Northern Cape, South Africa. An area 12 miles (19 km) long and 3 miles (4.8 km) wide was identified as suitable, with the first runs in October 2019. Further runs in November 2019 achieved a top speed of 628 miles per hour (1,011 km/h), the eighth vehicle to attain a land speed of over 600 miles per hour (970 km/h).

Timeline

Inception

The Bloodhound project was announced on 23 October 2008 at the London Science Museum by Lord Drayson – then Minister of Science in the UK's Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills – who first suggested the project in 2006 to land speed record holders Richard Noble and Andy Green, a pilot and Wing Commander serving in the RAF.[6][7] The two men, between them, have held the land speed record since 1983.[8]

In 1983, Noble, a self-described engineer and adventurer[9] reached 633 mph (1,019 km/h) driving a turbojet-powered car named Thrust2 across the Nevada desert.[10] In 1997, he headed the project to build ThrustSSC, which was driven by Green at 763 mph (1,228 km/h), thereby breaking the sound barrier, a first for a land vehicle (in compliance with Fédération Internationale de l'Automobile rules).[10] Green is also Bloodhound LSR's driver.[11]

The Bloodhound project was named for the Bristol Bloodhound surface-to-air missile, a project that Bloodhound Chief Aerodynamicist Ron Ayers had previously worked on.[12]

The project was at first based in the former Maritime Heritage Centre on the Bristol harbourside, next to Brunel's SS Great Britain. In 2013 the project relocated to a larger site in Avonmouth.[13] The head offices of the project moved to Didcot, Oxfordshire in late 2015.[14]

2017 tests

Runway testing of up to 200 miles per hour (320 km/h) took place on 26, 28 and 30 October 2017 at Newquay Airport, Cornwall.[15][16]

2018 change of ownership

In May 2018, the team announced plans for high speed testing at 500–600 mph (800–970 km/h) in May 2019, and then a 1,000 mph (1,600 km/h) run in 2020.[17] However, the company backing the project, Bloodhound Programme Ltd, went into administration (bankruptcy) in late 2018 leaving a funding gap of £25 million, which put the venture's future into question.[18][19]

The project was "axed" in December 2018, with plans to sell off the remaining assets.[20] Later that month, Yorkshire entrepreneur Ian Warhurst stepped in to rescue the project by buying the assets and intellectual property, including the car, for an undisclosed sum.[21][22]

2019 tests

In March 2019, it was announced that Warhurst had formed a new company called Grafton LSR Ltd. to manage the project, which became the car's legal owner. The company said in a statement that Warhurst was trying to save the project with new sponsors and partners.[23][24][25]

The name of the new team became 'Bloodhound LSR' (for Land Speed Record). The car and the project's headquarters moved to SGS Berkeley Green University Technical College in Berkeley, Gloucestershire near Gloucester.[26]

High speed testing of the car took place at the Hakskeen Pan in October and November 2019. Test runs driven by Green began on 25 October, using only a Rolls-Royce Eurojet EJ200 engine, with an expectation of reaching 400–500 mph (640–800 km/h).[27] The car achieved 501 mph (806 km/h) on 6 November 2019,[28] and a final top speed of 628 mph (1,011 km/h) on 16 November, making it the eighth vehicle to attain a land speed of over 600 mph.[2]

2020–2022

Lack of funds prevented the fitting of the Nammo rocket in 2020, and combined with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, this meant the opportunity to run the vehicle in 2021 was lost. In January 2021, Warhurst said the vehicle was up for sale and it was reported that the team had moved on to other projects.[29] Warhurst stepped aside as CEO in August 2021 and Stuart Edmondson, the project's Engineering Operations Manager for the previous five years, took over the role.[30] When interviewed in July 2022 Edmundson stated that, while on hold, the Bloodhound LSR project was "very much alive" and a new land speed record could be achieved very quickly if new investment could be secured. Edmundson also reported that the project had adopted a new environmental focus, with the aim of achieving a net zero carbon land speed record.[31]

The vehicle currently resides at Coventry Transport Museum.

Design

Car

The car was designed by Bloodhound's Chief Aerodynamicist Ron Ayers and Chief Engineer Mark Chapman, along with aerodynamicists from Swansea University.[32][33]

Bloodhound LSR is designed to accelerate from 0 to 800 mph (1,300 km/h) in 38 seconds and decelerate using airbrakes at around 800 mph, a parachute at a maximum deployment speed of around 650 mph (1,050 km/h) and disc brakes below 200 mph (320 km/h).[34] The force on the driver during acceleration would be 2.5 g (two-and-a-half times his body weight) and up to 3 g during deceleration.[35]

Aerodynamics

The aerodynamics of Bloodhound have been carefully calculated to make sure the car is safe and stable, particularly because it will create a shockwave when it reaches the speed of sound.[36]

The College of Engineering at Swansea University has been heavily involved in the aerodynamic shape of the vehicle from the start. Dr Ben Evans and his team used Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) technology designed by Professor Oubay Hassan and Professor Ken Morgan to provide an understanding of the aerodynamic characteristics of the proposed shape, at all speeds, including predicting the likely vertical, lateral and drag forces on the vehicle and its pitch and yaw stability.[37][38][39][40] This technology, originally developed for the aerospace industry, was validated for a land-going vehicle during the design of ThrustSSC.

Propulsion

Three prototype Eurojet EJ200 jet engines developed for the Eurofighter and bound for a museum were loaned to the project.[41] The car will use one EJ200 to provide around half the thrust and power the car to 650 mph (1,050 km/h).[42][15] A custom monopropellant rocket designed by Nammo will be used to add extra thrust for the world land speed record runs. For the 1,000 mph (1,600 km/h) runs, the monopropellant rocket will be replaced with a hybrid rocket from Nammo.[15] A third engine, a Jaguar supercharged V-8 is used as an auxiliary power unit to drive the oxidiser pump for the rocket, although this will be replaced by an electric motor.[15]

Initially Bloodhound SSC was going to use a custom hybrid rocket motor being designed by Daniel Jubb. The rocket was successfully tested at Newquay Airport in 2012.[43] However, constraints on cost, time and test facilities led to a decision to instead use a rocket designed by Norwegian company Nammo.[44]

At first the plan was that the car would use a Nammo hybrid rocket or cluster of rockets, to be fuelled by solid hydroxyl-terminated polybutadiene and liquid high-test peroxide oxidiser.[44] This plan was revised in 2017 and the car will use a monopropellant rocket for the land speed record runs.[45]

For the car to achieve 800 mph (1,300 km/h), the monopropellant rocket would need to produce around 40 kN (8992 lbf) of thrust and the EJ200 jet engine 90 kN (20,232 lbf) in reheat.[46]

Wheels

For low-speed testing at Cornwall Airport Newquay in 2017, the car was fitted with four runway wheels based on those of an English Electric Lightning fighter jet with refurbished original tyres.[47] These were replaced for the high-speed test runs in the desert in South Africa in 2019 by four 90-centimetre (35 in) diameter wheels weighing 95 kg (209 lb), forged from an aircraft-grade aluminium zinc alloy.[48] These were designed to spin at up to 10,200 rpm and resist centrifugal forces of up to 50000 g at the rim.[49][50]

Wheel bearings

Three Timken high-speed (DN around 1,000,000 at full speed) tapered roller bearings support each wheel.[51][52] When the car's mass increased to 7,500 kg (16,500 lb), Timken recalculated bearing life to be 50 hours, or a 5000% safety factor given the less than 1 hour run time.[53]

Construction

The car was built at sites in Bristol and Avonmouth.[54][13] A full-scale model was unveiled at the 2010 Farnborough International Airshow,[55] when it was announced that Hampson Industries would begin to build the rear chassis section of the car in the first quarter of 2011 and that a deal for the manufacture of the front of the car was due. The car was largely completed by October 2017 when full reheat static testing was undertaken with the jet engine at Cornwall Airport Newquay followed by low speed test runs.[56]

Further construction was carried out before the project went into administration and the car was then completed at Berkeley before high speed testing.

Testing locations

Early in the project, Swansea University's School of the Environment and Society was enlisted to help determine a new test site for the record runs because the test site for the ThrustSSC record attempt had become unsuitable.[57] The venue chosen for high speed testing and for the land speed record runs was Hakskeen Pan in the Mier area of the Northern Cape, South Africa, on a track measuring 12 miles (19 km) long. The local community cleared 16,500 tonnes of stones by hand from an area measuring 22 million square metres to create space for 20 tracks each 10 metres wide, as the car cannot run twice on the same strip of desert.[58][59][60][61]

Low speed runway testing of over 200 mph (320 km/h) occurred on 26, 28 and 30 October 2017 at Cornwall Airport Newquay.[56]

High speed testing at Hakskeen Pan began in October 2019. The car achieved 628 mph (1,011 km/h) on its final run on 16 November 2019.

Education and STEM outreach

The Bloodhound Project had an education component designed to inspire future generations to take up careers in science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) by showcasing these subjects and interacting with young people and students, in partnership with engineering companies including Rolls-Royce.[62] Bloodhound-related education activities are provided by Bloodhound Education Ltd, a standalone charity registered in 2016.[63] The charity's Bloodhound Education Centre is at SGS Berkeley Green UTC.[64]

References

- Noble, Green and Team Target 1,000MPH Record Archived 10 October 2018 at the Wayback Machine Thursday, 23 October 2008

- Amos, Jonathan (16 November 2019). "Bloodhound land speed racer blasts to 628mph". BBC News: Science. Retrieved 16 November 2019.

- "Supersonic car targets 1,000mph". BBC News. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Jonathan M. Gitlin (24 November 2018). "Bloodhound SSC: How do you build a car capable of 1,000mph?". Ars Technica. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- "Facts and Figures". The Bloodhound Project. June 2012. Archived from the original on 2 January 2015. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- "Supersonic car targets 1,000mph". BBC News: Science & Environment. 22 October 2008. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Khan, Urmee (23 October 2008). "Bloodhound SSC: British supercar designed to break world land speed record unveiled". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "1997: Land Speed Record". Guinness World Records. 18 August 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Noble, Richard (1999). Thrust. London: Bantam Books. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-553-81208-4.

- "FIA World Land Speed Records". Federation Internationale de l'Automobile. 10 June 2012. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Bloodhound. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- English, Andrew (10 March 2014). "The 1000 MPH Car Does Not Exist—Yet". Popular Mechanics. Retrieved 12 December 2018.

- Media, Insider. "Bloodhound relocates in Avonmouth". Insider Media Ltd. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "1,000mph world record rocket car team moves into Oxfordshire headquarters". Oxfordshire Guardian. Archived from the original on 8 March 2018. Retrieved 18 March 2016.

- Amos, Jonathan (26 October 2017). "First public runs for 1,000mph car". BBC News: Science. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Bloodhound SSC Reaches 210mph in Its First Public Test Before 1,000mph Land Speed Record Attempt". interestingengineering.com. 28 October 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Amos, Jonathan (16 May 2018). "Delay for Bloodhound high-speed trials". Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Bloodhound SSC to make first speed record attempt in 2019". 16 May 2018.

- Amos, Jonathan (15 October 2018). "1,000mph car hits financial roadblock". BBC News. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Bloodhound supersonic car project axed". BBC News. 7 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- "Bloodhound supersonic car project saved". BBC News. 17 December 2018. Retrieved 17 December 2018.

- Bloodhound SSC project saved from administration by British entrepreneur Engineering & Technology, 17 December 2018. Retrieved 9 February 2020

- "Revitalised Bloodhound gets new livery and headquarters". Bloodhound. 20 March 2019. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Gitlin, Jonathan M. (24 March 2019). "Good news for the 1,000mph car as Bloodhound gets a new owner". Ars Technica. Retrieved 24 March 2019.

- "Bloodhound History". Bloodhound. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Bloodhound Diary: Back on track, Andy Green (World Land Speed Record Holder), BBC News Online, 2019-03-29

- Amos, Jonathan (25 October 2019). "Bloodhound takes first drive across the desert". BBC News: Science. Retrieved 27 October 2019.

- Marriage, Ollie (6 November 2019). "The Bloodhound LSR just hit 501mph". Top Gear. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- Speed, Richard (26 January 2021). "One careful driver: Make room in the garage... Bloodhound jet-powered car is up for sale". The Register. Archived from the original on 26 January 2021. Retrieved 19 February 2021.

- "British Bloodhound land speed record project resurrected". Driving.co.uk from The Sunday Times. 20 August 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Bloodhound SSC project still alive and now aiming for first carbon zero land speed record". Driving.co.uk from The Sunday Times. 1 July 2022. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- "Me and My Motor: Ron Ayers, the supersonic car designer behind Bloodhound SSC". Sunday Times Driving. 29 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Mark Chapman – chief engineer, Bloodhound SSC". The Engineer. 18 April 2010. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Bloodhound LSR – Braking systems". Bloodhound Education. 4 September 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Career interview: The fastest mathematician on Earth". plus.maths.org. 1 September 2009. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Bloodhound video: Managing the aerodynamics of supersonic shockwaves". imeche.org. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Evans, B.; Morton, T.; Sheridan, L.; Hassan, O.; Morgan, K.; Jones, J. W.; Chapman, M.; Ayers, R.; Niven, I. (1 February 2013). "Design optimisation using computational fluid dynamics applied to a land–based supersonic vehicle, the BLOODHOUND SSC". Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization. 47 (2): 301–316. doi:10.1007/s00158-012-0826-0. ISSN 1615-1488. S2CID 253680425.

- Evans, Ben (2011). "Computational Fluid Dynamics Applied to the Aerodynamic Design of a Land-Based Supersonic Vehicle". Numerical Methods for Partial Differential Equations. 27: 141–159. doi:10.1002/num.20644. S2CID 56569633.

- Evans, Ben; Rose, Chris (9 April 2014). "Simulating the aerodynamic characteristics of the Land Speed Record vehicle BLOODHOUND SSC" (PDF). Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, Part D: Journal of Automobile Engineering. 228 (10): 1127–1141. doi:10.1177/0954407013511071. ISSN 0954-4070. S2CID 55967643.

- "Swansea University help design Bloodhound SSC". Swansea University. Archived from the original on 29 October 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- "Bloodhound diary: Rolls of advice". 24 May 2013. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Bloodhound LSR – engines". Bloodhound Education. 22 August 2019. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Amos, Jonathan (3 October 2012). "Rocket test roars over Newquay". Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Amos, Jonathan (19 December 2013). "1,000mph car to use Norwegian rocket". Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "James Clayton Lecture – BLOODHOUND SSC: the next stage. Interview with Richard Noble". imeche.org. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Rocket engine". The Bloodhound Project. Archived from the original on 23 February 2019. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- at 12:27, Gareth Corfield 26 October 2017. "The UK's super duper 1,000mph car is being tested in Cornwall". The Register. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Amos, Jonathan (14 March 2015). "Supersonic car gets its superwheels". Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Andy Green's Diary: Finally the news we've all been waiting for…... Bloodhound is going to the desert this year!". Bloodhound. 1 August 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Morris, Steven (30 September 2019). "Bloodhound car aiming for land speed record has final UK tests". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "Timken to provide wheel bearing solution for 1,000 mph car". Bloodhound SSC. 2 September 2009. Archived from the original on 27 July 2017. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Andy Green's Diary – September 2019". Bloodhound LSR. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

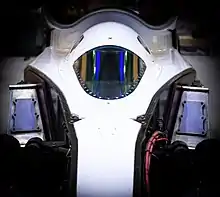

- "Bloodhound diary: Cockpit-centred view". BBC News. 19 March 2012. Retrieved 9 December 2021.

- "Supersonic Bloodhound car to be built in Bristol". BBC. 23 November 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

- Amos, Jonathan (19 July 2010). "Model of Bloodhound supersonic car unveiled". BBC News. Retrieved 19 July 2010.

- "BLOODHOUND Dynamic testing – Run reports". 16 October 2017.

- "Swansea University Desert Selection Programme". Swansea University. Archived from the original on 28 October 2008. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- "Bloodhound catches the scent of a world record as desert spec car revealed for first time". Bloodhound. 23 October 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Hudson, Paul (16 July 2019). "Bloodhound land speed record team announces high-speed tests at site of 1,000mph attempt". The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Green, Andy (8 November 2016). "Bloodhound Diary: Super-track for supercar". Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- Mafika (8 March 2013). "SA clears path for 1 000 mph rocket car". Brand South Africa. Retrieved 12 January 2020.

- "Bloodhound Education". 2 March 2012. Retrieved 4 September 2017.

- "Bloodhound Education Ltd, registered charity no. 5081957". Charity Commission for England and Wales.

- "The Bloodhound Education Centre". Bloodhound Education. 13 December 2019. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

External links

- Official website

- Andy Green's Bloodhound SSC diary for the BBC

- Bloodhound SSC at Swansea University

- Bloodhound SSC at the AoC (Association of Colleges) 2010 Annual Conference

- Amos, Jonathan (22 October 2008). "Supersonic car targets 1,000mph". BBC News – Science & Environment. Retrieved 24 October 2008.

- Semple, Ian (23 October 2008). "Faster than a bullet – the 1,000mph car". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 October 2008.

- Piper, John (20 March 2009). "Unleash the Bloodhound: How to design a 1,000mph car". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 March 2009.