Live event support

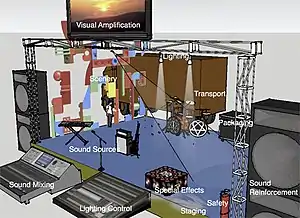

Live event support includes staging, scenery, mechanicals, sound, lighting, video, special effects, transport, packaging, communications, costume and makeup for live performance events including theater, music, dance, and opera. They all share the same goal: to convince live audience members that there is no better place that they could be at the moment. This is achieved through establishing a bond between performer and audience.[1] Live performance events tend to use visual scenery, lighting, costume amplification and a shorter history of visual projection and sound amplification reinforcement.[2]

Visual support

Introduction

Live event visual amplification is the display of live and pre-recorded images as a part of a live stage event. Visual amplification began when films, projected onto a stage, added characters or background information to a production. 35 mm motion picture projectors became available in 1910 - but which theatre or opera company first used a movie in a stage production is not known. In 1935, less costly 16 mm film equipment allowed many other performance groups and school theaters to use motion pictures in productions.

In 1970, closed circuit video cameras and videocassette machines became available and Live Event Visual Amplification came of age. For the first time live closeups of stage performers could be displayed in real time. These systems also made it possible to show pre-recorded videos that added information & visual intensity to a live event.

One of the first video touring systems was created by video designer TJ McHose in 1975 for the rock band The Tubes using black and white television monitors.[3]

In 1978, TJ McHose designed a touring color video system that enlarged performers at the Kool Jazz Festivals in sports stadiums across the United States.[4]

Introduction

Live event visual reinforcement is the addition of projected lighting effects and images onto any type of performance venue.

Visual Reinforcement began more than 2000 years ago. In China during the Han Dynasty, Shadow puppetry was invented to "bring back to life" Emperor Wu's favorite concubine. Mongolian troops spread Shadow play throughout Asia and the Middle East in the 13th century. Shadow puppetry reached Taiwan in 1650, and missionaries brought it to France in 1767.[5]

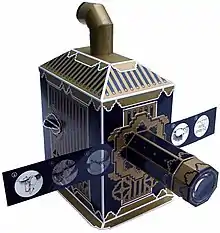

The next major advance in Visual reinforcement for events was the magic lantern, first conceptualized by Giovanni Battista della Porta in his 1558 work Magiae naturalis. The Magic Lantern became practical by 1750 with the oil lamp and glass lenses. Special effect animation attachments were added in the 1830s. In 1854, the Ambrotype positive photographic process on glass made Magic lantern slide creation much less expensive.

Magic lanterns were greatly improved by the application of limelight to live stage production in 1837 at Covent Garden Theatre[6] and improved again when electric arc lighting became available in 1880.

In 1910, Adolf Linnebach invented the Linnebach lantern, a lensless wide angle glass slide projector.[7]

In 1933, the Gobo metal shadow pattern for the ellipsoidal spotlight allowed images to appear and disappear by dimmer control.

In 1935, 16 mm Kodachrome film projectors added the first fully animated visual reinforcement to live events.

Timeline

- 1600: Shadow play leather or paper puppets cast shadows on a translucent screen

- 1760: magic lantern painted slide projector Phantasmagoria ghost effects projector

Magic Lantern image projector

Magic Lantern image projector - 1905: Linnebach lantern[8] Munich Opera

- 1933: Gobo metal shadow mask adds patterns to ellipsoidal spotlights

- 1940: Overhead projector Later used for psychedelic light shows

- 1950: Slide projector 35 mm Kodak Carousel

- 1965: Thomas Wilfred describes[9] A highly detailed system to create event scenery using rear projections

- 1967: Liquid Projector psychedelic Liquid light shows

- Joshua Light Shows at The Fillmore for The Grateful Dead, Big Brother and the Holding Company and many other Summer of Love bands

Audio support

Introduction

A sound reinforcement system is professional audio, was first developed for movie theatres in 1927 when the first ever talking picture was released, called The Jazz Singer. Movie theatre sound was greatly improved in 1937 when the Shearer Horn system debuted. One of the first large-scale outdoor public address systems was at 1939 New York World's Fair.

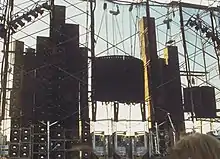

In the 1960s, rock and roll concerts promoted by Bill Graham at The Fillmore created a need for quickly changeable sound systems. In the early 1970s, Graham founded FM Productions to provide touring sound and light systems. By 1976 in San Francisco, the technical debate over infinite baffle vs horn-loaded enclosures, and line arrays vs distributed driver arrays, was ongoing at FM because of the proximity of The Grateful Dead and their scene Ultrasound, John Meyer, and others. But at that time there were parallel developments in other parts of the United States - Showco (Dallas) and Clair Bros (Philadelphia) had different approaches; Clair in particular was moving in the direction of modular full-range enclosures. They would rig as many as needed (or clients like Bruce Springsteen could afford) in whatever configuration they thought would cover a particular venue. Stanal Sound in southern California used fiberglass futuristic looking equipment for artists like Kenny Rogers.

Timeline

- 1876: Loudspeaker Alexander Graham Bell

- 1878: Carbon microphone / amplifier

- 1924: Loudspeaker - moving-coil -patent Chester W. Rice & E. Kellogg

- 1924: Loudspeaker - ribbon Walter H. Schottky

- 1930: Vacuum tube amplifier

- 1937: Loudspeaker - Shearer Horn movie theatre system

- 1939: public address outdoor system 1939 New York World's Fair

- 1945: Loudspeaker - coaxial Altec "Voice of the Theatre"

- 1953: Loudspeaker - electrostatic -patent Arthur Janszen

Touring sound reinforcement system

Touring sound reinforcement system - 1953: Microphone - wireless

- 1965: Loudspeaker - woofer

- 1965: Loudspeaker - subwoofer

- 1970: Microphone - condenser

- 1974: Loudspeaker - Sensurround movie sound system for "Earthquake"

- 1974: Loudspeaker - Dolby Stereo 70 mm Six Track

- 1975: Loudspeaker - touring - McCune JM-3 John Meyer

- 1979: Loudspeaker - Meyer Sound Laboratories - Grateful Dead wall of sound

- 1983: Loudspeaker - THX movie sound system for Star Wars

Transportation support

Efficient and timely transportation is essential for live event productions. [10]

Touring packaging

Well designed touring systems unload from the truck gently, roll easily into their stage location, connect to each other quickly. A well designed system includes duplicates of critical components and "field-replaceable" items such as cables, switches and fuses. Every component should be protected by a well padded road case that has room for all connector cables and allows easy access to the components for fast cable re-patching to bypass a bad component and for repairs during a tour. The road cases need good ventilation and for outdoor use should be white to minimize solar heat buildup. Road case sizes should be modular to pack tightly together on the truck.

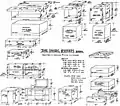

Packaging images

Touring video system schematic

Touring video system schematic Touring cases schematic for Video display system Kool Jazz Festival 1978

Touring cases schematic for Video display system Kool Jazz Festival 1978 Color video projector in road case -Kool Jazz Festival

Color video projector in road case -Kool Jazz Festival

See also

References

- "The importance of live performances | News, Sports, Jobs - Adirondack Daily Enterprise". Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- Schreibman, Susan; Siemens, Ray; Unsworth, John (2008-04-15). A Companion to Digital Humanities. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99986-8.

- Inc, Nielsen Business Media (1979-09-22). Billboard. Nielsen Business Media, Inc.

{{cite book}}:|last=has generic name (help) - Dolecheck, Cameren. "Radio: Think BIG with Visualization" (PDF). askcbi.org/.

- "Southeast Asian arts - Shadow-puppet theatre". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- Wolfreys, Julian (2007-01-01). Dickens to Hardy, 1837-1884: The Novel, the Past and Cultural Memory in the Nineteenth Century. Macmillan International Higher Education. ISBN 978-1-137-08619-8.

- "Linnebach lantern". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- Burris-Meyer and Cole (1938). Scenery For The Theatre.Little, Brown and company pp 246-7 Projected Scenery Effects

- Wilfred, Thomas (1965) Projected Scenery: A Technical Manual

- "Entertainment Cargo - Useful Links". Archived from the original on 2008-09-28. Retrieved 2009-05-12.