Bolesław V the Chaste

Bolesław V the Chaste (Polish: Bolesław Wstydliwy; 21 June 1226 – 7 December 1279) was Duke of Sandomierz in Lesser Poland from 1232 and High Duke of Poland from 1243 until his death, as the last male representative of the Lesser Polish branch of Piasts.

| Bolesław V the Chaste | |

|---|---|

| High Duke of Poland | |

| Reign | 1243–1279 |

| Predecessor | Konrad I of Masovia |

| Successor | Leszek II the Black |

| Duke of Sandomierz | |

| Reign | 1227–1230 1232–1279 |

| Predecessor | Boleslaus I of Masovia |

| Successor | Leszek II the Black |

| Born | 21 June 1226 Stary Korczyn |

| Died | 7 December 1279 (aged 53) Kraków |

| Burial | |

| Spouse | Kinga of Poland |

| House | House of Piast |

| Father | Leszek I the White |

| Mother | Grzymisława |

| Religion | Roman Catholic |

Birth and nickname

Bolesław V was born on 21 June 1226 at Stary Korczyn,[1] as the third child and only son of Leszek I the White by his wife Grzymisława, a Rurikid princess of disputed parentage.

Named after his great-grandfather Bolesław Wrymouth, the numeral V was assigned to him in the Poczet królów Polskich.[2] His nickname of "Chaste" (Latin: Pudicus[3]), appeared relatively early and was already mentioned in the Rocznik franciszkański krakowski.[4] It was given to him by his subjects because of the vows of chastity that Bolesław V and his wife Kinga of Hungary had jointly taken; for this reason, their marriage was never consummated.

Youth

Father's death

On 24 November 1227, during the Congress of Gąsawa, Bolesław V's father, Leszek the White, was killed. Like his own father and paternal grandfather before him, he was orphaned at young age. After Duke Leszek's death many people claimed the custody of his only son. The nobility of Kraków wanted the regency to be exercised by Dowager Duchess Grzymisława, jointly with the local voivode and bishop; however, this was contrary to the treaty of mutual inheritance signed in 1217 by Leszek and Władysław III Spindleshanks, under which it was agreed that in the event of the death of one of them, the other would take the government of his domains and custody of his minor children.

On 6 December 1227 Casimir I of Kuyavia - who probably represented his father Konrad I of Masovia at the funeral of Leszek I - advanced his father's claims over the custody of Bolesław V and his inheritance as his closest male relative.[5] Due to the lack of response, Konrad I came to Skaryszew to negotiate with Grzymisława and the local nobility in the first half of March 1228, with regard to assuming the guardianship of his nephew during his minority.[6] The nobility, especially the Gryfici family, preferred the rule of Władysław III Spindleshanks, but at that point he was in the midst of fighting with his nephew Władysław Odonic and was unable to claim his rights. Konrad I then appeared in the northern part of Kraków, but at his side were only the Topór and Sztarza families,[7] and so this attempt to take the Seniorate failed. According to Kazimierz Krotowski, the absence from Lesser Poland was the cause of the Prussian invasion to Masovia.[8]

Adoption by Władysław Spindleshanks

On 5 May 1228, a meeting was organized in Cienia between Władysław Spindleshanks and a delegation of Kraków nobles, which included Bishop Iwo Odrowąż; voivode Marek Gryfita; Pakosław Awdaniec the Old, voivode of Sandomierz; and Mściwój, castellan of Wiślica. Under the terms of the meeting, Władysław agreed to the adoption of Bolesław V, making him his successor over Kraków and Greater Poland. After the meeting, Władysław arrived in Kraków, where Grzymisława formally gave him the rule of the city. The dowager duchess and her son received the Duchy of Sandomierz, where she exercised the regency.

Shortly afterwards Władysław Odonic escaped from prison and the fight for Greater Poland was resumed. Władysław Spindleshanks was forced to leave Kraków. Then the local nobility, with the consent of Grzymisława, called Henry the Bearded to Kraków, but only to rule as a governor.[9] In the summer of 1228 Konrad I of Masovia attacked Kraków, but was defeated at the Battle of Skała by Henry I's son, Henry the Pious. However, a year later Konrad I captured Henry the Bearded and occupied Sieradz-Łęczyca and later Sandomierz, removing Grzymisława from power, despite resistance from the local nobility. In 1230 Władysław Spindleshanks, with the help of Henry I, made an unsuccessful attempt to recover his lands. Władysław died one year later in exile in Racibórz.

Władysław's will named Henry the Bearded heir to Kraków and Greater Poland. In 1231, with the support of the Gryfici family, Henry obtained the rule over Sandomierz, after Grzymisława (who feared for the future of the inheritance of her infant son) surrendered the regency. During 1231-1232 Henry fought against Konrad for Lesser Poland; by the autumn of 1232 Henry finally obtained control over Lesser Poland and Konrad could only keep Sieradz-Łęczyca.

Imprisonment by Konrad I of Masovia

In 1233 Konrad I of Masovia captured Grzymisława and her son after personally robbing and beating them, according to a bull of Pope Gregory IX. Bolesław V and his mother were imprisoned firstly in Czersk and then in Sieciechów. The humiliations to the dowager duchess continued there, including a slap in the face by Konrad I.

Henry the Bearded decided to rescue the imprisoned prince and his mother; shortly thereafter Bolesław and Grzymisława managed to escape from the monastery of Sieciechów with the help of Kraków voivode Klement of Ruszcza and Mikołaj Gall, who was in charge of the prisoners. Both Klement and Mikołaj bribed the guards, who were busy drinking, and did not pay attention to the prisoners, who left the monastery in disguise. Jan Długosz described the events as follows:

- When one night the guards after drink and feast forgot their duties, abandoned their posts and quietly during the night Duke Bolesław and his mother secretly left the monastery.

For safety reasons, Henry the Bearded hid Bolesław and his mother in the fortress of Skała near the valley of the Prądnik river. Then, on behalf of her son, Grzymisława renounced his rights over Kraków to Henry. In 1234 a war between Henry and Konrad for Lesser Poland broke out. Thanks to Archbishop Pełka, the Treaty of Luchani was signed in August of that year, under which Bolesław received Sandomierz and gave several castles to Henry. In June 1235, Pope Gregory IX approved the Treaty of Luchani; however, shortly afterwards Konrad invaded Sandomierz, and as a result of this invasion Bolesław lost the district of Radom.

Henry the Bearded died in 1238, and his son Henry the Pious succeeded him. Like his father, he took the regency of Bolesław and his Duchy of Sandomierz. In 1239 in Wojnicz, the 13-year-old Bolesław met his bride, the 15-year-old Kinga (also known as Kunigunda), daughter of King Béla IV of Hungary. The wedding was celebrated shortly thereafter. Kinga spent her first years in Sandomierz with her mother-in-law. On 9 July of that year, a meeting also took place in Przedbórz between Bolesław and Konrad, at which the Masovian ruler agreed to renounce his claims over Sandomierz. It was at this point that Bolesław began his personal government.

Fall of Kraków

In 1241 the first Mongol invasion of Poland occurred. In January the Mongols took Lublin and Zawichost. Bolesław, with his mother and wife, fled to Hungary at the side of his older sister Salomea, wife of the Hungarian prince Coloman, leaving his lands without his leadership. On 13 February the Mongols conquered and burned Sandomierz, and on 11 March he refused to participate in the Battle of Chmielnik. One month later, on 9 April, the Battle of Legnica took place, in which the army commanded by High Duke Henry II the Pious was defeated, and the duke himself was killed. After the defeat of the Hungarian army at the Battle of the Sajó River two days later (11 April) - where Prince Coloman was seriously injured and died shortly after - Bolesław V and his family (including Salomea, now a widow) fled to Moravia, and then eventually returned to Poland.

After the death of Henry the Pious, his eldest son, Bolesław the Bald, took the title of high duke; however, he did not appear in Kraków, where the government was exercised by Klement of Ruszcza on his behalf. Konrad I of Masovia took this opportunity, and despite the strong resistance of the knights and nobility, he finally entered Kraków on 10 July 1241. A few months later, the fortress of Skała, held by Klement of Ruszcza, capitulated. Despite his success, Konrad failed to gain the support of the local nobility, victims of Konrad's mercenaries (the Teutonic Order) themselves, who in 1243 appointed Bolesław the Chaste as their new ruler. On 25 May of that year the Battle of Suchodoły took place, in which the Lesser Poland and Hungarian (Sarmatian) troops, under the command of Klemens of Ruszcza, defeated the Masovian troops of Konrad. With this victory, Bolesław the Chaste regained the government over Kraków. Now at the age of 17, he was the high duke of Poland; however, he remained under the strong influence of his mother until her death. Later that year, Konrad tried to regain the control over Kraków and attacked Bolesław, but was again defeated.

Adulthood

Struggle with Konrad

Konrad I of Masovia until his death attempted to realize his ambition to become high duke and ruler of Kraków. In 1246, together with his son Casimir and supported by Lithuanian and Opole troops, he attacked Lesser Poland again. In the Battle of Zaryszów the troops of Bolesław were defeated. The duke of Kraków lost Lelów, but Kraków and Sandomierz managed to resist. The lack of funds for war forced Bolesław to take some properties of his wife, Kinga, which were paid only on 2 March 1257 during a meeting at Nowy Korczyn, when she received the district of Stary Sącz. In the autumn of 1246 was brought the final solution to the conflict when Bolesław retook Lelów. Konrad died on 31 August 1247, but his son Casimir continued the fight.

During 1254-1255 Bolesław sought the release of Siemowit I of Masovia and his wife, Pereyaslava, who were captured by his brother Casimir. They were finally released in the spring of 1255 after lengthy negotiations. In 1258 Bolesław the Pious started a long and destructive war against Casimir and his ally Świętopełk (Swantopolk) II for the castellany of Ląd. Bolesław the Chaste joined in the Greater Poland coalition against the duke of Kuyavia.

Between 29 September and 6 October 1259 Bolesław the Chaste, together with Bolesław the Pious, sacked Kujawy. A peace treaty was finally concluded on 29 November 1259. In 1260, Casimir I took over the fortress of Lelów. On 12 December during a meeting at Przedbórz, Bolesław the Chaste mediated the dispute between Casimir and Siemowit, which ended in a mutual treaty.

Cooperation with Hungary

Bolesław the Chaste and Bolesław the Pious were both allies of the Kingdom of Hungary. Their links with the Hungarians probably resulted from their family relationships, as both of their wives were daughters of King Béla IV and most of their Polish and Hungarian knights were descendants of the Sarmatian Iazyges, Siraces and Serboi. In 1245 both rulers supported the expedition of Rostislav Mikhailovich, who was the Hungarian candidate for the throne of Halych. On 17 August the Battle of Jarosław took place, where the Polish and Hungarian troops were defeated. Finally, a peace treaty was signed at Łęczyca.

In June and July 1253 Polish-Russian forces, including the army of Bolesław the Chaste, rushed to Moravia in support of the Hungarian expedition to Vindelicia (Austria), which was under the rule of King Ottokar II of Bohemia. The war failed to achieve a settlement, despite the Polish-Russian army looting several villages. The conflict ended with a treaty; at this time, Ottokar (with the help of Bishop Paweł of Kraków) tried to persuade Bolesław the Chaste to join at his side.

In 1260 another conflict erupted between Hungary and Bohemia, when the Hungarian prince Stephen organized a marauding expedition to the Duchy of Carinthia. From June to July 1260 Bolesław, with Leszek the Black, helped the Hungarians with troops in their fight against Bohemia. On 12 July the Battle of Kressenbrunn took place, which ended with the defeat of the Hungarian army.

On 29 January 1262 during a meeting at Iwanowice, Bolesław the Chaste promised to give military support to Bolesław the Pious in his conflict with Henry the White, who was a supporter of the Kingdom of Bohemia. On 7 June a second meeting took place at Danków, where peace negotiations with Henry took place. At this opportunity, Władysław Opolski tried unsuccessfully to make a quadruple alliance with the Bohemian king, Bolesław the Chaste, and Bolesław the Pious.

King Béla IV came into conflict with his son Stephen, which caused a civil war in Hungary. In March 1266 Bolesław and his wife Kinga arranged a meeting at Buda, at which Stephen was committed to maintain peaceful relations with his father, Ottokar II, Bolesław the Chaste, Leszek the Black, and Bolesław the Pious.

In 1270 the new King Stephen V of Hungary visited Bolesław the Chaste in Kraków, where they signed an eternal peace. In the same year, Stephen V renewed the war against Bohemia for the Babenberg inheritance, which ended in the defeat of Hungary. In 1271 Bolesław, with the help of Rurikid princes, organized an expedition to the Duchy of Wrocław, because Henry the White was an ally of Bohemia.

King Stephen V died on 6 August 1272, and after this the alliance between Bolesław the Chaste and the Kingdom of Hungary was completely broken. In 1277 Bolesław finally made a peace treaty with Bohemia at Opava. With the new king of Hungary, Ladislaus IV, a minor, Bolesław became an ally of the Kingdom of Bohemia; however, during the conflict between Ottokar and King Rudolph I of Germany, he opted for the Hungarian side. On 26 August 1278 Bolesław was present in the decisive Battle on the Marchfeld, where Ottokar was defeated and killed.

Christianization of the Yotvingians

One of the aims of Bolesław's foreign policy was the Christianization of the Yotvingians. During 1248-1249 he organized an expedition against them, supported by Siemowit I. However, the expedition ended in failure.

Between 1256-1264 the Yotvingians invaded and plundered Lesser Poland. In the spring of 1264, Bolesław organized a retaliatory expedition against them, which ended with a victory of the Kraków-Sandomierz troops and the death of the Yotvingian prince Komata. For the Christianization of this tribe, Bolesław created a bishopric in Łuków on the northeastern border of Lesser Poland. In this cause he counted on the support of his sister Salomea and Pope Innocent IV, who in 1254 issued a special document. In the end the mission failed.

Second Mongol invasion

Prince Daniel of Galicia was at the side of Bolesław as an ally of Hungary in the conflict with the Kingdom of Bohemia. In 1253 after the war with Bohemia, the relation between Bolesław and Daniel was good. Daniel visited Kraków, where he met the papal legate Opizo, who wanted to crown him. The coronation finally took place at Drohiczyn on the Bug River. Bolesław and his sister Salomea supported this event, because they wanted Daniel and his principality to acquire the Latin rite. The second Mongol invasion of Poland shattered those plans.

In November 1259 the Mongols and Ruthenians invaded and destroyed Sandomierz, Lublin and Kraków; Bolesław fled to either Hungary or Sieradz, ruled by Leszek the Black. In February 1260 the Mongols left Lesser Poland, and Bolesław then returned to his lands. At this point his relations with Daniel of Galicia improved; in 1262 they signed a treaty in Tarnawa.

After Daniel's death in 1265 a Lithuanian-Russian army invaded and ravaged the Lesser Poland districts of Skaryszew, Tarczek, and Wiślica. During 1265−66 Bolesław fought against Daniel's son Shvarn and brother Vasilko Romanovich, who helped the Lithuanians in their invasion into Lesser Poland. On 19 June 1266 Shvarn was defeated at the Battle of Wrota. The conflict ended in 1266, when Bolesław abandoned his expeditions to Yotvingia.

In July 1273 the Lithuanians invaded Lublin. In retaliation, Leszek the Black organized an expedition to Yotvingia in December of that year. In 1278 the Lithuanians again invaded Lublin, and they clashed with Leszek's army at the Battle of Łuków.

Adoption of Leszek the Black

Because Bolesław and his wife Kinga made a vow of chastity, their marriage was childless. In 1265 Bolesław adopted Leszek the Black as his heir. In 1273 Władysław Opolski organized a military expedition to Kraków, because he refused to accept the adoption. On 4 June the Battle of Bogucin Mały took place, where the army from Opole-Racibórz was defeated. At the end of October, Bolesław made a retaliatory expedition against Opole-Racibórz; however, the forces were limited only to destroy specific areas of the duchy. In 1274 Władysław and Bolesław V the Chaste decided to conclude a peace, under which the Duke of Opole-Racibórz gave up his claims to the throne of Kraków.

Internal policies

Bolesław V paid particular attention to urban development. On 27 February 1253 he granted privileges to the city of Bochnia. On 5 June 1257 during a meeting at Kopernia near Pińczów, he granted the Magdeburg rights to the district of Kraków, and a year later to the city of Nowy Korczyn. In 1264, the city of Skaryszew also received the rights, and in 1271 during a meeting at Kraków, the city of Jędrzejów also obtained the rights. The implementation of the German-styled law led to the rapid economic development in the principality, which experienced losses, up to 75% in population alone, due to Mongol raids.

In addition, the reform in the administration of the salt mines of Bochnia and Wieliczka was noteworthy. In 1251 deposits of halite were discovered in Bochnia; previously, only brine had been found there. Bolesław V prompted the district to mine the salt, which became a source of regular income.

During his reign, Bolesław took special care of the church, and above all, to the Bishopric of Kraków. In 1245, thanks to the efforts of Bolesław's sister Salomea, a Poor Clare monastery was founded in Zawichost. On 28 August 1252 during a meeting at Oględów, the Duke and his mother Grzymisława granted an immunity privilege to the Bishopric, which guaranteed to the local clergy greater autonomy in economic and judicial matters. On 17 September 1253, thanks to the joint efforts of Bolesław and the bishop of Kraków, Pope Innocent IV canonized Stanisław (Stanislaus) of Szczepanów. On 8 May 1254 celebrations were held in Kraków to honour Saint Stanislaus, including a meeting of the Piast princes. On 18 June another meeting took place at Chroberz, where Bolesław confirmed the privileges granted to the Bishopric of Kraków at Oględów. In 1257 a synod was held in Łęczyca, where it was established that any ruler who kidnapped a bishop would be automatically excommunicated, and his domains placed under the interdict. Between 11–12 June 1258 a meeting was held at Sandomierz, at which Bolesław approved further privileges for the Church in Lesser Poland. At the invitation of Bolesław V and his wife Kinga, the Franciscans came to Kraków around 1258.

Death

Bolesław the Chaste died on 7 December 1279.[10] Jan Długosz recorded the event as follows:

- He was deeply grieved not only by his own people, but also by the neighboring nations because of the modesty and majesty that he showed.

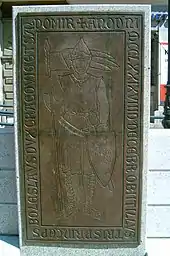

His funeral took place three days later, on 10 December.[11] He was buried in the Church of St. Francis of Assisi in Kraków. There is a gravestone with the inscription:

- Anno Domini MCCLXX obiit ilustrissimus princeps et dnus, Vladislaus dictus pius dux Cracov.

Kazimierz Stronczyński[12] alleged that the gravestone was false, but the fact that contemporary sources established that Bolesław's body was placed in the church, does not raise any objections.[13]

After the death of her husband, Kinga entered the Poor Clares convent in Stary Sącz. By virtue of the previous agreement, Leszek II the Black inherited Kraków and Sandomierz.

Church foundations

In 1263 Bolesław founded a church dedicated to Mark the Evangelist in Kraków (pl: Kościół św. Marka w Krakowie) built in the Gothic style.

Notes

- Date provided by the Rocznik kapituły krakowskiej and Rocznik Traski. See: K. Jasiński: Rodowód Piastów małopolskich i kujawskich, Poznań – Wrocław 2001, p. 44.

- August Bielowski: Pomniki dziejowe Polski, vol. 3, Lwów 1878, p. 294; K. Jasiński: Rodowód Piastów małopolskich i kujawskich, Poznań – Wrocław 2001, p. 44.

- According to Aleksander Krawczuk the proper translation was "modest". See: Skromne jak dzieciątko in: wyborcza.pl [retrieved 11 February 2015].

- Rocznik franciszkański krakowski, p. 46: "Lestko genuit [...] dueem Bolezlaum Pudicum". See. K. Jasiński: Rodowód Piastów małopolskich i kujawskich, Poznań – Wrocław 2001, p. 44.

- J. Szymczak: Udział synów Konrada I Mazowieckiego w realizacji jego planów politycznych, "Rocznik Łódzki" 29, 1980, p. 9.

- Benedykt Zientara: Henryk Brodaty i jego czasy, ed. TRIO, Warsaw 2006, p. 292

- W. Semkowicz: Ród Awdańców w wiekach średnich, vol. 3, p. 163

- Kazimierz Krotoski: Walka o tron krakowski w roku 1228, ed. W. L. Anczyc i Sp., 1895, p. 348.

- Władysław Spindleshanks formally retained the rights of high duke, and in 1228 Henry I the Bearded did not accept the title of Duke of Kraków.

- Kalendarz katedry krakowskiej, p. 190 (under 7 December entry): "Dux Bolezlaus Pudicus filius Lestkonis obiit".

- Rocznik franciszkański krakowski, p. 50.

- Kazimierz Stronczyński: Mniemany grobowiec Bolesława Wstydliwego w Krakowie, "Biblioteka Warszawska" 24, 1849, p. 502.

- Latopis hipacki, p. 880; Udział Rusi, p. 175, footnote 25.

Bibliography

- Tomasz Biber, Anna Leszczyńska, Maciej Leszczyński: Poczet Władców Polski. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Podsiedlik-Raniowski i Spółka, 2003, pp. 73–78.

- Kazimierz Jasiński: Rodowód Piastów małopolskich i kujawskich. Poznań – Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Historyczne, 2001, pp. 43–49.

- Andrzej Marzec: Bolesław V Wstydliwy [in:] Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999, pp. 191–197.

- Andrzej Marzec: Henryk I Brodaty [in:] Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999, pp. 380–382.

- Krzysztof Ożóg: Władysław III Laskonogi [in:] Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999, pp. 125–127.

- Stanisław Andrzej Sroka: Leszek Czarny [in:] Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999, p. 204.

- Maciej Wilamowski: Konrad I Mazowiecki [in:] Piastowie. Leksykon biograficzny. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999, pp. 261–263.

- Jerzy Wyrozumski: Historia Polski do roku 1505. Warszawa: Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe, 1984, pp. 130–132.