Bonaventure Giffard

Bonaventure Giffard (1642–1734) was a Roman Catholic bishop who served as the Vicar Apostolic of the Midland District of England from 1687 to 1703 and Vicar Apostolic of the London District of England from 1703 to 1734.

The Right Reverend Bonaventure Giffard | |

|---|---|

| Vicar Apostolic of the London District | |

| |

| Appointed | 14 March 1703 |

| Term ended | 12 March 1734 |

| Predecessor | John Leyburn |

| Successor | Benjamin Petre |

| Other post(s) | Titular Bishop of Madaurus |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 22 April 1688 by Ferdinando d’Adda |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1642 |

| Died | 12 March 1734 (aged 91–92) |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Roman Catholic |

| Previous post(s) | |

Life

He was the second son of Andrew Giffard of Chillington, in the parish of Brewood, Staffordshire, by Catherine, daughter of Sir Walter Leveson, born at Wolverhampton in 1642. His father was slain in a skirmish near Wolverhampton early in the Civil War. The family still exists, and traces a pedigree without failure of heirs male from before the Conquest.[1]

Bonaventure was educated in the English College, Douai, and thence proceeded on 23 October 1667 to complete his ecclesiastical studies in Paris. He received the degree of D.D. in 1677 from the Sorbonne, having previously been ordained as a secular priest for the English mission. King James II soon after his accession made Giffard one of his chaplains and preachers.[2]

He showed his moral courage by urging the King to put away his mistress, Catherine Sedley, Countess of Dorchester, a demand echoed by most of the King's councillors.[3] The King was in no way offended by Giffard's request which he took "very kindly, he (Giffard) being a very religious man", and complied with it in the short term at least, although the Council were told sharply to mind their own business. The King, with a rare touch of humour, said sarcastically that he had not realised they had all become priests too.[4]

On 30 November 1686, he and Dr. Thomas Godden disputed with Dr. William Jane and Dr. Simon Patrick before the king and the Earl of Rochester concerning the real presence. In 1687, Pope Innocent XI divided England into four ecclesiastical districts, and allowed James to nominate persons to govern them. Accordingly, Giffard was appointed the first vicar-apostolic of the midland district by propaganda election on 12 Jan (N.S.) 1687-8. His briefs for the vicariate and the see of Madaura, in partibus, were dated 30 Jan 1687-8, and he was consecrated in the banqueting hall at Whitehall on Low Sunday, 22 April (O.S.) 1688, by Ferdinando d'Adda, Archbishop of Amasia, in partibus, and nuncio apostolic in England. Some writers say, however, that Bishop John Leyburn was the consecrator. Giffard's name is attached to the pastoral letter from the four catholic bishops which was addressed to the lay Catholics of England in 1688.[1]

On the death of Samuel Parker, Bishop of Oxford, who had been appointed president of Magdalen College by the king in spite of the election of John Hough by the fellows, Bishop Giffard, by royal letters mandatory, was appointed president. He was installed by proxy on 31 March 1688, and on 15 June took possession of his seat in the chapel, and lodgings belonging to him as president. His brother, Andrew Giffard, a secular priest, and eleven other members of the church of Rome were then elected fellows. The college was practically converted into a Roman Catholic establishment, and mass was celebrated in the chapel. By virtue of special authority from the king, Giffard on 7 August expelled several fellows who had refused to acknowledge him as their lawful president. On 3 October, William Sancroft, Archbishop of Canterbury, with other bishops then in London, advised the king to restore the president (Hough) and fellows. James, according to Macaulay, did not yield till the vicar-apostolic Leyburn declared that in his judgment the ejected president and fellows had been wronged. Giffard and the other intruders were in their turn ejected by Peter Mews, Bishop of Winchester, visitor of the college, on 25 October 1688.[2] Luttrell relates that the Catholic fellows and scholars embezzled much of the college plate; but Bloxam remarks that it is only due to them to say that a diligent inspection completely disproved the charge.

At the revolution Giffard and Bishop Leyburn were seized at Faversham, on their way to Dover, and were actually under arrest when James II was brought into that town. Both prelates were committed to prison, Leyburn being sent to the Tower of London, and Giffard to Newgate. They were both liberated on bail by the Court of King's Bench on 9 July 1690, on condition that they would transport themselves beyond sea before the end of the following month.[1]

In 1703, Giffard was transferred from the Midland to the London district, on the death of Leyburn. He also took charge of the western district from 1708 to 1713, in the absence of Bishop Michael Ellis. In this he was aided by his brother Andrew, his vicar-general, till the latter died, 14 September 1714.[2] Dodd says he lived privately in London, under the connivance of the government, who gave him very little disturbance, being fully satisfied with the inoffensiveness of his behaviour. It is certain, however, that he was exposed to constant danger. He told Cardinal Sacripanti in 1706 that for sixteen years he had scarcely found anywhere a place to rest with safety. For above a year he found a refuge in the house of the Venetian ambassador. Afterwards, he again lived in continual fear and alarm. In 1714, he wrote that between 4 May and 7 October, he had had to change his lodgings fourteen times, and had but once slept in his own lodging. He added: 'I may say with the apostle, in carceribus abundantius. In one I lay on the floor a considerable time, in Newgate almost two years, afterwards in Hertford gaol, and now daily expect a fourth prison to end my life in'.[1]

In 1720, he applied to the holy see for a coadjutor. Henry Howard, brother to the Duke of Norfolk, was accordingly created bishop of Utica, in partibus, and nominated to the coadjutorship, cum jure successionis, on 2 October 1720, but he died before the end of the year, and in March 1720–1 the propaganda appointed Benjamin Petre coadjutor in his stead.

Death

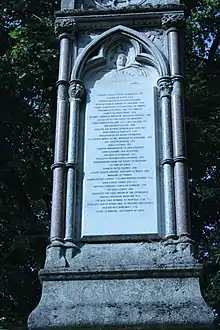

Giffard died at Hammersmith on 12 March 1733–4, in his ninety-second year, and was buried in the churchyard of Old St. Pancras. The tomb disappeared when part of the graveyard was being cleared to enable the expansion of the Midland Railway, but the inscription upon it is printed in ‘Notes and Queries,’ 3rd ser. xii. 191. His name is listed on the Burdett-Coutts Memorial to the important lost graves in the graveyard.

In 1907 his remains, together with those of his brother Andrew and sister Anne, were re-interred at St Edmund's College, Ware.[5]

Giffard bequeathed his heart to Douay College, and it was buried in the chapel, where a monument with an epitaph in Latin was erected to his memory.[1]

Dodd highly commends Giffard for his charity to the poor, and Granger says he was much esteemed by men of different religions. He procured many large benefactions for the advancement of the catholic religion and the benefit of the clergy, and at his death left about 3,000 shillings for the same ends.[1]

Two of his sermons preached at court were published separately in 1687, and are reprinted in ‘Catholic Sermons,’ 2 vols. Lond. 1741 and 1772. Many interesting letters written by him are printed in the ‘Catholic Miscellany’ for 1826 and 1827. There is a fine picture of him at Chillington, a life-size, half-length. His portrait has been engraved by Claude du Bosc, from a painting by H. Hysing.[1]

Further reading

References

- Cooper 1890.

- MacErlean, Andrew. "Bonaventure Giffard." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 12 January 2019

- Kenyon, J.P. Robert Spencer, 2nd Earl of Sunderland 1641-1702 Gregg Revivals 1992 p.129

- Kenyon p.129

- Nicholas Schofield The History of St Edmund's College (2014) p.104

Sources

- Cooper, Thompson (1890). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 21. London: Smith, Elder & Co. pp. 291–292.

- MacErlean, Andrew Alphonsus (1909). . In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company.