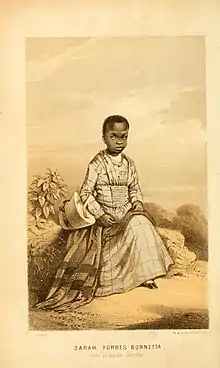

Sara Forbes Bonetta

Sara Forbes Bonetta, otherwise known as Sally Forbes Bonetta, (born Aina or Ina; 1843 – 15 August 1880),[2] was ward and goddaughter of Queen Victoria. She was a princess of the Egbado clan of the Yoruba people in West Africa, who was orphaned during a war with the nearby Kingdom of Dahomey as a child, and was later enslaved by King Ghezo of Dahomey. She was given as a "gift" to Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the British Royal Navy and became a goddaughter of Queen Victoria. She married Captain James Pinson Labulo Davies, a wealthy Lagos philanthropist.

Sara Forbes Bonetta | |

|---|---|

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Sara Forbes Bonetta photographed by Camille Silvy in 1862 | |

| Born | Aina (also Ina)[1] 1843 Oke Odan, Yorubaland |

| Died | 15 August 1880 (aged 36–37) Funchal, Madeira Island, Portugal |

| Cause of death | Tuberculosis |

| Resting place | Funchal, Madeira Island, Portugal |

| Other names | Sarah Forbes Bonetta Sally Forbes Bonetta |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Relatives | John Randle (physician) (son-in-law) Ameyo Adadevoh (great-great-granddaughter) |

Early life

Originally named Aina (or Ina),[3] she was born in 1843 in Oke-Odan, an Egbado Yoruba village in West Africa which recently became independent from the Oyo Empire (present-day southwestern Nigeria) after its collapse.[4] The Kingdom of Dahomey was under subjugation by Oyo, and it was a historical enemy of the Yoruba people. Oyo and Dahomey began to engage in a war in 1823 after Ghezo, the new King of Dahomey, refused to pay annual tributes to Oyo. During Oyo's war with Dahomey, Oyo was weakened and destabilised by the Islamic jihads launched by the growing Sokoto Caliphate.[5] The Oyo Empire began to disintegrate by the 1830s, fragmenting Yorubaland into various small states. Dahomey's army began to expand eastwards into Oyo's former and defenseless Egbado territory, capturing Egbado slaves in the process.[4]

In 1848, Oke-Odan was invaded and captured by the army of Dahomey. Aina's parents died during the attack and other residents were either killed or sold into the Atlantic slave trade. Aina ended up in the court of King Ghezo of Dahomey as a young child slave. Dahomey was a major West African power that immensely profited from the Atlantic slave trade. After the British abolition of slavery, King Ghezo fought against British attempts to curtail Dahomey's exportation of slaves. Biographer and historian of Africa Martin Meredith quotes King Ghezo telling the British, "The slave trade has been the ruling principle of my people. It is the source of their glory and wealth. Their songs celebrate their victories and the mother lulls the child to sleep with notes of triumph over an enemy reduced to slavery."[6]

In July 1850, Captain Frederick E. Forbes of the Royal Navy arrived to West Africa on a British diplomatic mission, where he unsuccessfully attempted to negotiate with King Ghezo to end Dahomey's participation in the Atlantic slave trade.[7] As was customary, Captain Forbes and King Ghezo exchanged gifts with each other. King Ghezo offered Forbes a footstool, rich country cloth, a keg of rum, ten heads of cowry shells, and a caboceers stool.[8] King Ghezo also offered him Aina, who was intended to be a gift for Queen Victoria. Forbes estimated that Aina was enslaved by King Ghezo for two years. Although her actual ancestry is unknown,[9] Forbes came to the conclusion that Aina was likely to have come from a high status background since she had not been sold to European slave traders.[8] Describing Aina in his journal, he wrote: "one of the captives of this dreadful slave-hunt was this interesting girl. It is usual to reserve the best born for the high behests of royalty and the immolation on the tombs of the deceased nobility…".[10]

Dahomey was notorious for mass executing its captives in spectacular human sacrifice rituals as part of the Annual Customs of Dahomey. Forbes was aware of Aina's potential deadly fate in Dahomey, and as he wrote in his journal, refusing Aina "would have been to have signed her death-warrant, which probably would have been carried into execution forthwith."[10][8] Captain Forbes accepted Aina on behalf of Queen Victoria and embarked on his journey back to Britain.[10]

Captain Forbes renamed her Sara Forbes Bonetta, after himself and his ship HMS Bonetta. Forbes initially intended to raise her himself. However, Queen Victoria was impressed by the young princess's "exceptional intelligence", and had the girl, whom she called Sally,[11] raised as her goddaughter in the British middle class.[11][12][13] In 1851, Sara developed a chronic cough, which was attributed to the climate of Great Britain. Her guardians sent her to school in Africa in May of that year, when she was aged eight.[11] She attended the Annie Walsh Memorial School (AWMS) in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The school was founded by the Church Missionary Society (CMS) in January 1849 as an institution for young women and girls who were relatives of the boys in the Sierra Leone Grammar School founded in 1845 (at first named CMS Grammar School). In the school register, her name appears only as Sally Bonetta, pupil number 24, June 1851, who married Captain Davies in England in 1862 and was the ward of Queen Victoria. She returned to England in 1855, when she was 12. She was entrusted to the care of Rev Frederick Scheon and his wife, who lived at Palm Cottage, Canterbury Street Gillingham. The house survives.[14] In January 1862, she was invited to and attended the wedding of Queen Victoria's daughter Princess Alice.[15]

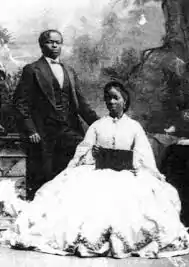

Marriage and children

She was later commanded by the Queen to marry Captain James Pinson Labulo Davies at St Nicholas' Church in Brighton, East Sussex, in August 1862, after a period spent in the town preparing for the wedding. During her subsequent time in Brighton, she lived at 17 Clifton Hill in the Montpelier area.[16]

Captain Davies was a Yoruba businessman of considerable wealth, and after their wedding the couple moved back to their native Africa, where they had three children: Victoria Davies (1863), Arthur Davies (1871), and Stella Davies (1873).[17] Sara Forbes Bonetta continued to enjoy such a close relationship with Queen Victoria that she and Bishop Samuel Ajayi Crowther were the only Lagos indigènes the Royal Navy had standing orders to evacuate in the event of an uprising in Lagos. Victoria Matilda Davies, Bonetta's first daughter, was named after Queen Victoria, who was also her godmother.[18] She married the successful Lagos doctor Dr. John Randle, becoming the stepmother of his son, Nigerian businessman and socialite J. K. Randle.[19] Bonetta's second daughter Stella Davies and Herbert Macaulay, the grandson of Samuel Ajayi Crowther, had a daughter together: Sarah Abigail Idowu Macaulay Adadevoh, named after her maternal grandmother Sara and her paternal grandmother Abigail.[17] A descendant of Sara's through her line was the Ebola heroine Ameyo Adadevoh. Many of Sara's other descendants now live in either Britain or Sierra Leone; a separate branch, the Randle family of Lagos, remains prominent in contemporary Nigeria.[18][20][21]

Death and legacy

Sara Forbes Bonetta died of tuberculosis on 15 August 1880[2] in the city of Funchal, the capital of Madeira Island, a Portuguese island in the Atlantic Ocean. In her memory, her husband erected an over-eight-foot granite obelisk-shaped monument at Ijon in Western Lagos, where he had started a cocoa farm.[22] The inscription on the obelisk reads:[2]

IN MEMORY OF PRINCESS SARAH FORBES BONETTA

WIFE OF THE HON J.P.L. DAVIES WHO DEPARTED THIS LIFE AT MADEIRA AUGUST 15TH 1880

AGED 37 YEARS

Her grave is number 206 in the British Cemetery of Funchal near the Anglican Holy Trinity Church, Rua Quebra Costas Funchal, Madeira.[23]

A plaque commemorating Forbes Bonetta was placed on Palm Cottage in 2016, as part of the television series Black and British: A Forgotten History.[24]

A newly commissioned portrait of Forbes Bonetta by artist Hannah Uzor went on display at Osborne House on the Isle of Wight in October 2020 as part of an effort by English Heritage to recognise black history in England.[25][26]

Forbes Bonetta was portrayed by Zaris-Angel Hator in the 2017 British ITV television series Victoria.[27]

Forbes Bonetta's life and story formed the basis for the novel Breaking the Maafa Chain by Anni Domingo, published by Jacaranda Books in 2021.

Gallery

.jpg.webp) Sara Forbes Bonetta by Camille Silvy

Sara Forbes Bonetta by Camille Silvy The English Cemetery in Funchal, Madeira

The English Cemetery in Funchal, Madeira Sarah Forbes Bonetta's gravestone, Madeira

Sarah Forbes Bonetta's gravestone, Madeira

See also

- Black British elite, the class that Forbes Bonetta belonged to

- Nigerian aristocracy, the class that Forbes Bonetta belonged to

- Nigerian bourgeoisie, the class that Forbes Bonetta married into

References

- Anim-Addo, Joan (2015). "Bonetta [married name Davies], (Ina) Sarah Forbes [Sally] (C. 1843–1880), Queen Victoria's ward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75453. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Elebute, Adeyemo (2013). The Life of James Pinson Labulo Davies: A Colossus of Victorian Lagos. Kachifo Limited/Prestige. p. 138. ISBN 9789785205763.

- Anim-Addo, Joan (2015). "Bonetta [married name Davies], (Ina) Sarah Forbes [Sally] (C. 1843–1880), Queen Victoria's ward". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/75453. ISBN 978-0-19-861412-8. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Elebute (2013), pp. 41–42

- Akinjogbin, I.A. (1967). Dahomey and Its Neighbors: 1708-1818. Cambridge University Press.

- Meredith, Martin (2014). The Fortunes of Africa. New York: PublicAffairs. p. 193. ISBN 9781610396356.

- "Black and Asian History and Victorian Britain / Sarah Forbes Bonetta and Family". Royal Collection Trust. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 9 October 2020.

- "Sarah Forbes Bonetta, Queen Victoria's African Protégée". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Picture World: Image, Aesthetics, and Victorian New Media, Rachel Teutolsky, Oxford University Press, 2020, p. 267

- Chiba, Akira. "Queen Victoria and the African Princess | MUSEYON BOOKS". Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- Rappaport, Helen (2003). Queen Victoria: A Biographical Companion. ABC-CLIO Biographical Companions. p. 307. ISBN 9781851093557.

- Wasson, Ellis (2009). A History of Modern Britain: 1714 to the Present. John Wiley & Sons. p. 235. ISBN 9781405139359.

- Marsh, Jan (19 November 2009). Black Victorians: Black People in British Art 1800–1900. Lund Humphries, University of Michigan. pp. 62, 86. ISBN 9780853319306. Archived from the original on 23 April 2022. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- Jordan, Nicola (16 October 2016). "Queen Victoria adopted my great-great grandma". Kent Online. Archived from the original on 29 May 2018. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- Higgen, Annie C. (1881). "Queen Victoria's African Protégée". Church Missionary Quarterly Token. Church Missionary Society. p. 6. Archived from the original on 19 September 2023. Retrieved 10 October 2020 – via Google Books.

- Collis, Rose (2010). The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton: (based on the original by Tim Carder) (1st ed.). Brighton: Brighton & Hove Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9564664-0-2.

- Elebute (2013), pp. 77–79

- Braimah, Ayodale (5 June 2014). "Bonetta, Sarah Forbes (1843–1880)". BlackPast. Archived from the original on 19 August 2014. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Adeloye, Adelola (1974). "Some early Nigerian doctors and their contribution to modern medicine in West Africa". Medical History. 18 (3): 275–93. doi:10.1017/s0025727300019621. PMC 1081580. PMID 4618303. Archived from the original on 21 June 2019. Retrieved 23 May 2015.

- "The Nineteenth Century: 1862 - Sarah Forbes Bonetta - The African Princess in Brighton". Brighton and Hove Black History. Brighton and Hove Black History Project. Archived from the original on 8 May 2003.

- "Sarah Forbes Bonetta (Sarah Davies) (1843-1880), Goddaughter of Queen Victoria:Image archive". London: National Portrait Gallery. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 30 September 2006.

- Elebute (2013), pp. 111–119

- Register of Burials, Church Archives, Holy Trinity Church, Funchal

- "Plaque commemorating Sarah Forbes Bonetta who was under the protection of Queen Victoria - BBC". Google Arts & Culture. Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- "Sarah Forbes Bonetta: Portrait of Queen Victoria's goddaughter on show". BBC News. 7 October 2020. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Brown, Mark (6 October 2020). "New portrait of Queen Victoria's African goddaughter unveiled". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

- Gordon, Naomi (20 December 2017). "Victoria creator "challenging" perspectives of the era". Digital Spy. Archived from the original on 26 February 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2020.

Further reading

- Walter Dean Myers (1999). At Her Majesty's Request: An African Princess in Victorian England. Scholastic Press. ISBN 978-0590486699.

- Kemi Morgan and Christine Bullock, eds, The making of Good Wives, Good Mothers, Leading Lights of Society. The Story of St Anne's School Ibadan. Y Books & Associated Bookmakers of Nigeria Ltd, 1989. ISBN 9783453246

- Oyinkan Ade-Ajayi, Heritage Schools Nigeria. Phoenix Visions World Limited, 2020. ISBN 1916032826

- John Van der Kiste, Sarah Forbes Bonetta: Queen Victoria's African Princess. A & F, 2018. ISBN 978-1719186377 1

The books state that she was the Acting Principal of CMS Female Institution in 1870, the school was founded in 1869, the first principal was Mrs Annie Roper wife of Reverend Roper of CMS Mission Ijaiye, Mrs Forbes Davies was succeeded by Rev & Mrs Henry Townsend

External links

- "In focus: Sarah Forbes Bonetta". Kamal Simpson talks to Clare Gittings about Sarah Forbes Bonetta, who was photographed by Camille Silvy and featured in the National Portrait Gallery, London. YouTube.

- The Lost Child (BBC documentary)