Borvo

Borvo or Bormo (Gaulish: *Borwō, Bormō) was an ancient Celtic god of healing springs worshipped in Gauls and Gallaecia.[1][2] He was sometimes identified with the Graeco-Roman god Apollo, although his cult had preserved a high degree of autonomy during the Roman period.[3]

Name

The Gaulish theonym Boruō means 'hot spring', 'warm source'. It stems from the Proto-Celtic verbal root *berw- ('boil, brew'; cf. Old Irish berbaid, Middle Welsh berwi), itself from Proto-Indo-European *bʰerw- ('boil, brew'; cf. Latin ferueō 'to be intensely hot, boil', Sanskrit bhurváni 'agitated, wild').[4][5] The Bhearú river (River Barrow) in Ireland has also been linked to this Celtic root.[6]

The variant Bormō could have emerged from a difference in suffixes or from dissimilation.[4][2] Known derivates include Bormanicus (Caldas de Vizela), from an earlier *Borwānicos, and Bormanus or Borbanus (Aix-en-Diois, Aix-en-Provence), from an earlier *Borwānos.[7][8] A goddess named Boruoboendoa, perhaps reflecting the Gaulish theonym *Buruo-bouinduā or *Buruo-bō-uinduā, has also been found in Utrecht.[9]

The toponyms Bourbon-l'Archambault, Bourbon-Lancy, Bourbonne-les-Bains, Boulbon, Bormes, Bourbriac, La Bourboule and Worms are derived from Borvo or from its variant Bormo.[4][2][7] The names of various small rivers in France, such as Bourbouillon, Bourban, and Bourbière, also stem from the theonym.[7]

Centres of worship

In Gaul, he was particularly worshipped at Bourbonne-les-Bains, in the territory of the Lingones, where ten inscriptions are recorded. Two other inscriptions are recorded, one (CIL 13, 02901) from Entrains-sur-Nohain[10] and the other (CIL 12, 02443) from Aix-en-Savoie in Gallia Narbonensis.[11] Votive tablets inscribed ‘Borvo’ show that the offerers desired healing for themselves or others.[12] Many of the sites where offerings to Borvo have been found are in Gaul: inscriptions to him have been found in Drôme at Aix-en-Diois, Bouches-du-Rhône at Aix-en-Provence, Gers at Auch, Allier at Bourbon-l'Archambault, Savoie at Aix-les-Bains, Saône-et-Loire at Bourbon-Lancy, in Savoie at Aix-les-Bains, Haute-Marne at Bourbonne-les-Bains and in Nièvre at Entrains-sur-Nohain.[13]

Findings have also been uncovered in the Netherlands at Utrecht,[14] where he is called Boruoboendua Vabusoa Labbonus, and in Portugal at Vizela and at Idanha-a-Velha, where he is called Borus and identified with Mars.[13] At Aix-en-Provence, he was referred to as Borbanus and Bormanus but at Vizela in Portugal, he was hailed as Bormanicus,[13] and at Burtscheid and at Worms in Germany as Borbetomagus.

Divine entourage

Borvo was frequently associated with a divine consort, usually Damona (Bourbonne, Bourbon-Lancy), but sometimes also Bormana when he was worshipped by the name Bormanus (Die, Aix-en-Diois).[15][2] Bormana was in some areas worshipped independently of her male counterpart, such as at Saint-Vulbas.[16][2]

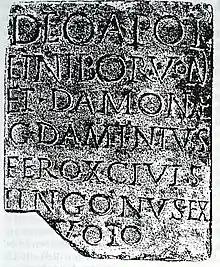

Deo Apol/lini Borvoni / et Damonae / C(aius) Daminius / Ferox civis / Lingonus ex / voto

— Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), 13: 05911. Bourbonne-les-Bains.

Bormano / et Borman[ae] / P(ublius) Sappinius / Eusebes v(otum) s(olvit) / l(ibens) m(erito)

— Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), 12: 01561. Boubon-Lancy.

Borvo bore similarities to the goddess Sirona, who was also a healing deity associated with mineral springs.[17] According to some scholars, Sirona may have been his mother.[15]

In other areas, Borvo's partner is the goddess Bormana. Bormana was, in some areas, worshipped independently of her male counterpart.[18] Gods like Borvo, and others, equated with Apollo, presided over healing springs, and they are usually associated with goddesses, as their husbands or sons.[19] He is found in Drôme at Aix-en-Diois with Bormana and in Saône-et-Loire at Bourbon-Lancy and in Haute-Marne at Bourbonne-les-Bains with Damona but he is accompanied by the ‘candid spirit’ Candidus in Nièvre at Entrains-sur-Nohain.[13] In the Netherlands at Utrecht as Boruoboendua Vabusoa Lobbonus, he is found in the company of a Celtic Hercules, Macusanus and Baldruus.[13]

References

- MacKillop 2004, s.v. Borvo.

- Busse & vaan de Weil 2006, pp. 230–231.

- Green 1986, p. 162: "Borvo, like Belenus, appears more often by himself than linked with Apollo, emphasising the essentially Celtic nature of the cult."

- Delamarre 2003, p. 83.

- Matasović 2009, p. 63.

- Monnier, Nolwena (2019). "Nommer la nature : toponymie de la nature dans la Topographia Hibernica de Gerald of Wales". Études irlandaises (44–1): 31–46. doi:10.4000/etudesirlandaises.6884. ISSN 0183-973X.

- Charrière 1975, pp. 130–131.

- Quintela, Marco (2005). "Celtic Elements in Northwestern Spain in Pre-Roman times". e-Keltoi: Journal of Interdisciplinary Celtic Studies. 6 (1). ISSN 1540-4889.

- Delamarre 2003, pp. 79, 83.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), 13: Tres Galliae et Germanae.

- Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum (CIL), 12: Gallia Narbonensis.

- MacCulloch, J. A. (1911). The Religion of the Ancient Celts.

- "Société de Mythologie Française (SMF)". Archived from the original on 2003-02-07. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- Garrett S. Olmsted, "The gods of the Celts and the Indo-Europeans", page 427

- MacKillop 2004, s.v. Borvo.

- Miranda Green. Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend. Thames and Hudson Ltd. London. 1997

- Paul-Marie Duval. 1957-1993. Les dieux de la Gaule. Presses Universitaires de France / Éditions Payot. Paris.

- Miranda Green. Dictionary of Celtic Myth and Legend. Thames and Hudson Ltd. London. 1997

- The Religion of the Ancient Celts: Chapter XII. River and Well Worship

Bibliography

- Busse, Peter E.; vaan de Weil, Caroline (2006). "Borvo/Bormo/Bormanus". In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. pp. 195–200. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Charrière, Georges (1975). "La femme et l'équidé dans la mythologie française". Revue de l'histoire des religions. 188 (2): 129–188. ISSN 0035-1423. JSTOR 23668651.

- Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionnaire de la langue gauloise: Une approche linguistique du vieux-celtique continental. Errance. ISBN 9782877723695.

- Green, Miranda J. (1986). The Gods of the Celts. A. Sutton. ISBN 978-0-389-20672-9.

- MacKillop, James (2004). A dictionary of Celtic mythology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860967-1.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.