Jack (playing card)

A Jack or Knave, in some games referred to as a bower, is a playing card which, in traditional French and English decks, pictures a man in the traditional or historic aristocratic or courtier dress, generally associated with Europe of the 16th or 17th century. The usual rank of a jack is between the ten and the queen.

History

The earliest predecessor of the knave was the thānī nā'ib (second or under-deputy) in the Mamluk card deck. This was the lowest of the three court cards and like all court cards was depicted through abstract art or calligraphy. When brought over to Italy and Spain, the thānī nā'ib was made into an infantry soldier or page ranking below the knight card. In France, where the card was called the valet, the queen was inserted between the king and knight. The knight was subsequently dropped out of non-Tarot decks leaving the valet directly under the queen. The king-queen-valet format then made its way into England.

As early as the mid-16th century the card was known in England as the knave which originally meant 'boy or young man', as its German equivalent, Knabe, still does. In the context of a royal household it meant a male servant without a specific role or skill; not a cook, gardener, coachman, etc. The French word valet means the same thing. Knave became a derogatory word because royal households had so many of these young men who went swaggering around the streets picking fights, molesting girls and generally making nuisances of themselves. It evolved to mean 'young manservant or henchman'.[1]

The word 'Jack' was in common usage in the 16th and 17th centuries to mean any generic man or fellow, as in Jack-of-all-trades (one who is good at many things), Jack-in-the-box (a child's toy), or Jack-in-the-Pulpit (a plant).

The term became more entrenched in card play when, in 1864,[2] American cardmaker Samuel Hart published a deck using "J" instead of "Kn" to designate the lowest-ranking court card. The knave card had been called a jack as part of the terminology of the game All Fours since the 17th century, but this usage was considered common or low class. However, because the card abbreviation for knave was so close to that of the king ("Kn" versus "K"), the two were easily confused. This confusion was even more pronounced after the markings indicating suits and rankings were moved to the corners of the card, a move which enabled players to "fan" a hand of cards without obscuring the individual suits and ranks. The earliest deck known of this type is from 1693, but such positioning did not become widespread until reintroduced by Hart in 1864, together with the knave-to-jack change. Books of card games published in the third quarter of the 19th century still referred to the "knave". Note the exclamation by Estella in Charles Dickens's novel Great Expectations: "He calls the knaves, jacks, this boy!" Nevertheless, in a few European countries, the equivalent of name 'knave' for this card continues to the present. For example, in Denmark, it is the Knægt, symbol B (for Bonde); in Sweden, the knekt, symbol Kn.

The German nickname of Bauer ("farmer" or "peasant") often used for the Jacks, appears in English as the loanword, Bower, used for the top trumps (usually Jacks) in games of the euchre family as well as some games of German origin where the Jacks play a significant role e.g. Reunion.

Representations

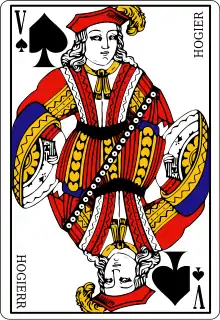

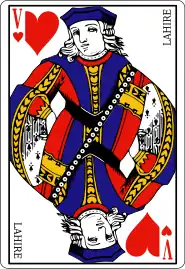

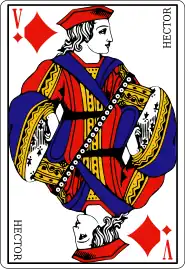

In the English pattern,[3] the jack and the other face cards represent no one in particular,[4] in contrast to the historical French practice, in which each court card is said to represent a particular historical or mythological personage. The valets in the Paris pattern have traditionally been associated with such figures as Ogier the Dane (a knight of Charlemagne and legendary hero of the chansons de geste) for the jack of spades;[5] La Hire (French warrior) for the Jack of Hearts; Hector (mythological hero of the Iliad) for the jack of diamonds; and Lancelot or Judas Maccabeus for the jack of clubs.[6][7]

In some southern Italian decks, there are androgynous knaves that are sometimes referred to as maids. In the Sicilian Tarot deck, the knaves are unambiguously female and are also known as maids.[8] As this deck also includes queens, it is the only traditional set to survive into modern times with two ranks of female face cards. This pack may have been influenced by the obsolete Portuguese deck which also had female knaves. The modern Mexican pattern also has female knaves.[9]

Poetry

The figure of the jack has been used in many literary works throughout history. Among these is one by 17th-century English writer Samuel Rowlands. The Four Knaves is a series of Satirical Tracts, with Introduction and Notes by E. F. Rimbault, upon the subject of playing cards. His "The Knave of Clubbs: Tis Merry When Knaves Meet" was first published in 1600, then again in 1609 and 1611. In accordance with a promise at the end of this book, Rowlands went on with his series of Knaves, and in 1612 wrote "The Knave of Harts: Haile Fellowe, Well Meet", where his "Supplication to Card-Makers" appears,[10] thought to have been written to the English manufacturers who copied to the English decks the court figures created by the French. The Knave of Hearts appears as a thieving antagonist in the traditional children's poem The Queen of Hearts

Example cards

The cards shown here are from a Paris pattern deck (where the rank is known as the "valet"), and include the historical and mythological names associated with them. The English pattern of jacks can be seen in the photo at the top of the article.

Trickster figure

The jack, traditionally the lowest face card, has often been promoted to a higher or the highest position in the traditional ranking of cards, where the ace or king generally occupied the first rank. This is seen in the earliest known European card games, such as Karnöffel, as well as in more recent ones such as Euchre. Games with such promotion include:

See also

- List of poker hand nicknames

- One-eyed jack

- "The Jack", a song by AC/DC, in which the playing card is a metaphor for an enthusiastic sexual partner with expertise-level "hand stuff" skills.

- The Knave of Hearts, a character in Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

- The Jack of Diamonds, a group of artists founded in 1909 in Moscow

- "Jack of Diamonds", a traditional folk song

- Jack of Diamonds, the title used by George de Sand in the 1994 anime Mobile Fighter G Gundam

- Knave of Hearts, a 1954 film directed by René Clément

- The Jack of Hearts (Jack Hart), a Marvel Comics superhero

- The Jack of Hearts, a 1919 short Western film

- "Lily, Rosemary and the Jack of Hearts", a song by Bob Dylan

- Pub (trans. The Jack), an album by Đorđe Balašević.

- King, Queen, Knave, a novel by Vladimir Nabokov first published in Russian under his pen name, V. Sirin

- "Jack of Speed", a song by Steely Dan, a group of musicians see Donald Fagen

References

- "Why is a jack part of the royal family in playing cards? Isn't he just a soldier?".

- Encyclopedia of Play in Today's Society, p. 290, Rodney P. Carlisle - Sage Publications INC 2009 ISBN 1-4129-6670-1

- English pattern at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Berry, John. (1998). "Frequently asked questions". The Playing-Card. Vol. 27-2. pp. 43-45.

- Games and Fun with Playing Cards by Joseph Leeming on Google Books

- The Four King Truth at the Urban Legends Reference Pages

- Courts on playing cards, by David Madore, with illustrations of the English and French court cards

- Tarocco Siciliano, early form at the International Playing-Card Society. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- Scotoni, Ralph. Mexican Pattern at Alta Carta. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- The Knave of Harts: Haile Fellowe, Well Meet, where his Supplication to Card-Makers by Samuel Rowlands (1600)

Good card-makers (if there be any goodness in you), Apparrell us with more respected care,

Put us in hats, our caps are worne thread-bare, Let us have standing collers, in the fashion;