Bawean

Bawean (Indonesian: Pulau Bawean) is an island of Indonesia located approximately 150 kilometers (93 miles) north of Surabaya in the Java Sea, off the coast of Java. It is administered by Gresik Regency of East Java province. It is approximately 15 km (9.3 mi) in diameter and is circumnavigated by a single narrow road. Bawean is dominated by an extinct volcano at its center that rises to 655 meters (2,149 feet) above sea level. Its population as of the 2010 Census was about 70,000 people, but more than 26,000 of the total (that is about 70% of the male population) were temporarily living outside, working in other parts of Indonesia, Singapore and Malaysia.[5] As a result, females constituted about 77% of the actual population of the island, which is thus often referred to as "the Island of Women" (Indonesian: Pulau Putri).[6][7] The 2020 Census revealed a population of 80,289,[8] while the official estimate as at mid 2022 was 82,887 (comprising 41,574 males and 41,313 females).[4]

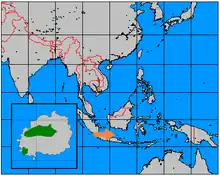

Bawean Location of Bawean (Indonesia) | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | South East Asia |

| Coordinates | 5°46′S 112°40′E |

| Archipelago | Greater Sunda Islands |

| Area | 196.97 km2 (76.05 sq mi)[1][2] |

| Highest elevation | 655 m (2149 ft)[3] |

| Highest point | unnamed |

| Administration | |

Indonesia | |

| Province | East Java |

| Largest town | Sangkapura |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 82,887[4] (mid 2022 estimate) |

| Additional information | |

| Time zone | |

The island territory is divided into two administrative districts, Sangkapura and Tambak. About 63.6% of the population (about 52,732 in 2022) live in the district of Sangkapura, centred on the town of that name located on the southern coast of the island.[1] The other 36.4% live in Tambak District, in the northern 40% of the island. The island has rich nature with many endemic species, such as Bawean deer which is only found on the island and is included to the IUCN Red List. There are several large underwater petroleum and gas fields around the island.

Etymology

The island's name is believed to originate from the Kawi (or Sanskrit) phrase ba (light) we (the sun) an (is) – thus: "having the sunlight". According to the legend, Javanese sailors wandering in the mist in 1350 named the island because they saw a glimpse of light around it; previously the island bore the Arabic name of Majidi.[9][10][11][12]

During the Dutch colonization in the 18th to the 20th centuries, the island was renamed Lubok, but the locals and even the Dutch continued to use the name Bawean.[13][14] The Dutch name fell out of use in the 1940s.

As a linguistic variation, the island is also called Boyan and its natives Boyanese. These names are also common in Malaysia and Singapore, being brought there by numerous visitors from Bawean.[11][12] Another popular appellation is the island of women (Indonesian: Pulau Putri). This originates from the predominance of the actual female population, as since the 19th century most males have taken part-time jobs outside Bawean. So whereas the nominal female population percentage amounted to about 52% in 2009, the actual fraction (corrected for residents abroad) approximated 77%. This imbalance has become the subject of national and international studies.[5][6]

History

Pre-colonial period

The name Bawean means "sunlight exists" in Sanskrit and was encountered by shipwrecked sailors in the 14th century, in reference to their excitement upon seeing clear skies after enduring fierce storms at sea.

The island endures in its indigenous practice of dukun, a shamanistic role of traditional society.

It is uncertain when humans first settled on Bawean. In the early Middle Ages ships sailing across the Java Sea often used the harbor on the island. The first records of permanent settlements on the island date to the 15th century.[15] Most of the references to Bawean in regional (mostly Javanese) sources of the 16–17th centuries are associated with visits to the island of Muslim preachers. Mass conversion of islanders to Islam began after the death in 1601 of the local Raja Bebileono who favored animism and the arrival from Java of the Muslim theologian Sheik Maulana Umar Mas'ud.[16][15] His dynasty became independent from the Javanese States, and his great-great-grandson Purbonegoro, who ruled the island between 1720 and 1747 visited Java as a sovereign ruler.[17] The graves of Maulana and Purbonegoro are revered on the island, they are visited by Muslim pilgrims from other parts of Indonesia and are the main historical attractions of Bawean.[18]

Colonial period

Dutch sailors first visited Bawean during their trading expedition to Java led by the explorer Cornelis de Houtman – on 11 January 1597, the badly damaged expedition ship Amsterdam was abandoned and set on fire off the Bawean coast.[19] In the 17–18th centuries, the island was regularly visited by ships of the Dutch East India Company, which was strengthening its position in this part of the Malayan archipelago, and in 1743 officially came under its control. The Island had little economic value and was used as a resting stop for ships sailing between Java and Borneo.[13][20]

After the bankruptcy and liquidation of the East India Company in 1798, Bawean and all its other possessions came under the direct control of the Netherlands Crown. Whereas the island was governed by an appointed Dutch official,[14] native nobility retained certain influence, and the Muslim institutions of justice settled local court matters. The Bawean religious court (Indonesian: Pengadilan Agama Bawean) was established in 1882.[16]

Since the end of 19th century, men of the island began to regularly travel to work in the British colonial possessions in the Malay Peninsula, especially in Singapore.[6] The Dutch authorities do not interfere with the activities of foreign recruiters who visited the island, as Bawean, with about 30,000 people and 66 settlements was overpopulated.[6][14] The island was then producing tobacco, Indigo, cotton fabrics and coal, and exported the Bawean deer and local breed of horse.[14] Large-scale planting of teak started in the 1930s and resulted in deforestation of most of the island.[21]

World War II

During World War II, large-scale battles between the Japanese and Allied navies occurred in the vicinity of Bawean island, especially during the Dutch East Indies campaign of 1941–1942. On 25 February 1942, the island was captured by the Japanese troops. On 28 February, in the first Battle of the Java Sea, the Japanese sunk several Allied ships, killing the commander of the East Indies Fleet, Rear Admiral Karel Doorman, on the light cruiser HNLMS De Ruyter. The Second Battle of the Java Sea, also known as the Battle off Bawean, was fought on 1 March 1942. It resulted in sinking of all the participating Allied ships, including the heavy cruiser HMS Exeter and effective termination of the Anglo-Dutch resistance in the region.[22][23] In August 1945, the Japanese garrison on the island surrendered to the Anglo-Dutch forces.

Post–World War II

After the proclamation of the independent Republic of Indonesia on 17 August 1945 the island formally became a part of the new state. However, it remained de facto under Dutch control, and in February 1948, together with Madura and several other islands, was included in the quasi-independent state Madura promoted by the Government of the Netherlands.[24][25] It joined the Republic of the United States of Indonesia (Indonesian: Republik Indonesia Serikat) in December 1949, and finally the Republic of Indonesia in March 1950.[25][26]

Geography

The island is located in the Java Sea about 150 km (93 mi) north of the larger island of Madura. It has a nearly round shape with the diameter varying between 11 and 18 km (6.8 and 11.2 mi) and giving an average value of 15 km (9.3 mi).[5][14] The shores are winding and contain many small bays; there are many small sandy islands (noko), rocks and coral reefs off the coast with the size up to 600 m (2,000 ft).[3] The largest inhabited satellite islands are Selayar, Selayar Noko, Noko Gili, Gili Timur and Nusa.[27]

Most of the island is hilly, except for the narrow coast and a plain in the southwestern part; it is therefore also called locally as "island of 99 hills".[6] The highest point (655 m; 2,149 ft) is at the hill Indonesian: Gunung Tinggi (that literally means "high mountain"). The greatest heights are in the central and eastern parts of the island.[3] Here are a few caldera lakes, the largest being the Lake Kastoba (Indonesian: Danau Kastoba). It has an area of about 0.3 km2 (0.12 sq mi), depth of 140 m (460 ft), and is located at an altitude of about 300 m (980 ft).[3][28] There are several small rivers and waterfalls, the highest being Laccar and Patar Selamat, as well as hot springs such as Kebun Daya and Taubat.[27]

Climate

The climate is tropical monsoonal, slightly less humid than the average in this part of Indonesia. Annual and daily temperature fluctuations are small, with the average maximum of 30 °C (86 °F) and the average minimum of 24.5 °C (76.1 °F).[29] Rainy season lasts from December to March, and the average monthly precipitation ranges from 402 millimetres (15.8 in) in December to 23 mm (0.91 in) in August. Northwesterly and easterly winds dominate the rainy and dry periods, respectively.[3][29]

Geology

The island originated from a volcano located near its center. Igneous rocks make about 85% of its surface with occasional limestone, sandstone and dolomite.[3][30] The soil in low-lying coastal areas is mainly alluvial, with a predominance of sand and gray clay. At altitudes of 10–30 meters above sea level, older alluvial accretions show up as horizontal layers of brown clay, and the higher areas are dominated by red-brown laterite.[3]

The area is considered seismically active, with frequent tremors which are companied by landslides.[30][31] The island has deposits of coal[14] and onyx which are being mined from the early 2000s.[32][33] There are oil and gas fields in the underwater shelf around the island, which are among the largest in Indonesia. Their development started in the 1960s and is being conducted now by the national company Pertamina and several foreign companies.[34][35]

Flora and fauna

Historically, most of the island was covered by virgin rainforest, but (as a result of human activity) the total area has rapidly declined; by the end of the 20th century, forests were covering less than 10% of the island. About 15% of the land is now claimed by the cultivated common teak (Tectona grandis).[3][29]

The local jungles are characterized by dense low understory growth, with a predominance of ferns, bryophytes and orchids.[3] The most common tree species are Ficus, Nauclea and Symplocos adenophylla. Some plant species do not occur on nearby Java Island, such as Canarium asperum, Pternandra coerulescens, Pternandra rostrata, Champera manilana, Ixora miquelii, Phanera lingua and Irvingia malayana.[3][29] Mangrove bushes occur in some coastal areas on the island, with the main species being Sonneratia alba, Rhizophora mucronata, Bruguiera cylindrica and Lumnitzera racemosa.[3][29]

The fauna of Bawean Island are generally quite similar to the species found on Java. The most unique of the island's endemic local fauna is a diminutive species of deer, simply known as the Bawean deer (Hyelaphus kuhlii), which is also referred to as Kuhl's deer or the Bawean hog deer. It is considered a symbol of Bawean, and is protected by Indonesian law. Unfortunately, there are less than 250 individuals, of which more than 90% belong to a single population. With lower numbers, the deer population's genetic variability is at risk of “bottlenecking” (I.e., low population leading to inbreeding), thus, they are listed as "critically endangered" on the IUCN Red List.[21][36]

Bawean hosts other unique mammals, such as the crab-eating macaque (Macaca fascicularis), Sunda porcupine (Hystrix javanica), small Indian civet (Viverricula indica), and the Asian palm civet (Paradoxurus hermaphroditus). The most common birds are the black-crowned night heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), purple heron (Ardea purpurea), great frigatebird (Fregata minor) and the gull-billed tern (Gelochelidon nilotica). Reptiles are represented by various kinds of monitor lizard (Varanus sp.), as well as the giant reticulated python (Python reticulatus) and the fearsome saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus), the latter sometimes (rarely) swimming inland, upstream from the coast, albeit for short periods.[3][37]

Nature conservation measures were first taken when Bawean was under colonial administration of the Netherlands. In 1932, five forests with a total area of 4,556 hectares (11,260 acres) were declared natural reserves.[21] In 1979, two national (Indonesian) nature reserves were created, with areas of 3,832 and 725 hectares (9,470 and 1,790 acres), primarily to protect the density of forests, the main habitat of the Bawean deer.[3]

Administration

Bawean belongs to the province of East Java (Indonesian: Provinsi Jawa Timur). In 1975 it became a part of the Regency (kabupaten) of Gresik. The island is divided into two administrative districts (kecamatan): Sangkapura and Tambak; each district is based around the towns of the same names. Sangkapura District includes 17 villages,[27] and is headed by M. Suhami.[38] Tambak District contains 13 villages,[27] and is headed by B.S. Sofyan.[38] Their areas and populations at the 2010 Census[39] and the 2020 Census,[8] together with the official estimates as at mid 2022,[4] were as follows:

| Name of District (kecamatan) | Area in km2[27] | Pop'n Census 2010 | Pop'n Census 2020 | Pop'n Estimate mid 2022 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sangkapura | 118.27 | 45,755 | 50,612 | 52,732 |

| Tambak | 78.70 | 24,475 | 29,677 | 30,155 |

| Totals | 196.97 | 70,230 | 80,289 | 82,887 |

The two districts include 12 small offshore islands.

Economy and social activities

The main source of income for the majority of the Bawean population is money earned by relatives working abroad.[5][6] The islanders are mainly engaged in growth of rice, maize, potato and coconuts.[6] Yields are lower than in Java because of significantly lower levels of agricultural mechanization and more frequent droughts.[1] Other common economical activities include fishing and growth of teak.[6] The industry is represented by a few handicraft workshops. From 2006 onyx is being mined and in the central part of the island by several Taiwanese companies.[32]

In 2009, the island had about 30 schools. Many young people go for their studies to Java and rarely return to the island.[6] The island has several pharmacies and small clinics, but no hospital.[40] Despite lack of equipment, local athletes are among the best in the county, especially in table tennis and a popular in Southeast Asia ball game sepak takraw (wherein a liana-woven ball is kicked over the net).[41] Volleyball became popular in the 2000s with about 80 officially registered teams on the island.[41]

The main ring road runs along the coast of the island; it has a length of about 55 km and 33 km of it are in poor condition. There are motorised vehicles, but most travel is done by bicycle, horse and cart, or becak.[42] The main port of the island, Sangkapura, is connected with the settlements of northern coast of East Java and Madura. The busiest shipping route is Sangkapura – Gresik.

Tourism and attractions

Governments – both local and of Gresik – are attempting to appeal Bawean for tourists by advertising local natural attractions, which include the Lake Kastoba, hot springs Kebundaya and Taubat, waterfalls Lachchar and Patar Selamat, the caves in the central part of the island, sandy beaches and coral reefs on the coast. However, poor infrastructural development of the island, combined with its remoteness from Java, hinders the development of tourism here. In addition, some locals regard Kastoba as a sacred lake and protest visiting it by tourists.[43][44]

Bawean Airport

In early 2013, Bawean Airport had a runway of 800 m (2,600 ft) length, and at least two aviation companies made proposals to the local authority to fly to and from Bawean. The runway has since been extended to 1,200 m (3,900 ft) length and it can accommodate 50-seater aircraft.[45][46] As the local authority was not ready to operate the airport, they handed control of the airport over to the central government. It was predicted to operate in May 2015;[47] however, operations at the Harun Thohir Airport were officially begun in January 2016.

Demographics

The high migration hinders accurate count of the number of people living on the island. In 2009, the number of residents was 74,319, of which at least 26,000 were living abroad – in Malaysia, Singapore and, to a lesser extent, in Java and other areas in Indonesia.[6] The southern coast of the island is most densely populated with more than half of the islanders living in the city of Sangkapura.[3][6]

Between about 1900 and 1930, the population was stable at the level of 30,000. It then rose, from 29,860 in 1930 to 59,525 in 1964, owing to the improving living conditions and arrival of new settlers from Madura. The growth rate then decreased and remains at 1% or higher per year,[5] with the total population reaching just over 80,000 in 2020.[48]

Most people inhabiting the island in the 15–16th centuries were from Madura and, to a lesser extent, from Java islands. They were gradually mixed with traders, fishermen and pirates of Bugis and Malayan ethnicities coming from other parts of the Malay Archipelago.[5] They were later joined by migrants from the Sumatran city of Palembang, who formed a community and took a dominant position in trade. By the beginning of the 20th century Baweans represented a fairly homogeneous ethnic community, and while living abroad formed compact communities and identified themselves as Baweans rather than other Indonesian groups.[5][11]

Recent migrations to the island are small[5][6] and are mostly composed of Javanese people who have certain interests on the island. Several hundred Javanese live on the island of Gili Barat which is connected to Bawean with a dam. They are engaged in growing coconut palms (Cocos nucifera). Newcoming Javanese are distinguished from the old Javanese settlers who live in the village Diponggo and speak an old-Javanese dialect.[5]

A small Chinese community has existed on the island since at least the late 19th century. It is increasing both by natural growth and via mixed marriages of Baweans and Singaporeans.[5]

Baweans, working abroad form compact communities, some of which are known for over 150 years.[5][6] For example, there were at least 763 Baweans in Singapore in 1849, most of whom lived in the area known as Malay: Kampung Boyan (Bawean village). Later, districts with the same name appeared in several parts of Malaysia.[5] The largest migrations from the island occurred in the later 1940s – early 1950s, during the formation of Indonesia as an independent state and the associated political instability and economic difficulties. So in 1950, there were 24,000 Baweans in Singapore alone.[5] Most Baweans living abroad keep close ties with their relatives on the island, regularly visit them, and often return after several years of absence.[6]

The migrations from the island are mostly caused by lack of jobs in a small densely populated island and low incomes.[6] There are generations of recruitment agents in Singapore and Malaysia specializing on employment of Baweans, mainly as construction workers and sailors. This migration also became a part of life, it is believed on the island that a man is not mature enough until he spends several years abroad. So a poll in the 2008–2009 revealed that only 55% of the locals justified the departure by economic reasons, while 35% associated it with the traditions or a desire to gain life experience.[6]

Language and religion

Most population speaks a Bawean dialect, which is regarded as the most lexically and phonetically peculiar dialect of the Madurese language;[49] Baweans living in Singapore and Malaysia speak its slight variation called Indonesian: boyan selat.[11] Virtually the entire population knows, to a various degree, the official language of the country – Indonesian.[6] The predominant religion on the island is Sunni Islam, with some remnants of the traditional local beliefs.[5][31]

Lifestyle

Traditional dwellings are quite similar on the Madura and Bawean islands. They have a bamboo frame, with porch, often on low poles. The roof is traditionally covered with palm leaves or reeds, but tile is becoming increasingly popular.[43]

Local costume is closer to that of Java than Madura. Men wear sarong (a kind of kilt) and a long-skirted tunic, and women are dressed in sarong and a shorter jacket. There are Malayan and Bugis varieties of dress.[43] The Malayan influence is more noticeable in the customs, ceremonies and folk dances, where the Madura heritage is weak. Also absent on the island are such traditional Madura elements as bull races and sickle-shaped knives.[43]

The local cuisine is diverse and borrows from all local ethnicities. The traditional local pie stuffed with vegetables (usually potatoes) is popular in Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore under the name Indonesian: roti Boyan (Bawean bread).[50][51]

See also

References

- "Pertanian di Bawean Terancam Puso" (in Indonesian). Media Bawean. 21 March 2010. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Bab II: Analisa dan Situasi" (in Indonesian). Pemerintahan Kabupaten Gresik.

- "Cagar Alam Pulau Bawean (Bawean Island Nature Reserve), Suaka Margasatwa". UNEP—WCMC. Archived from the original on 15 September 2003.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, 2023.

- Ida Bagoes Mantra (12 March 2020). "Indonesian Labour Mobility to Malaysia (A Case Study: East Flores, West Lombok, And The Island Of Bawean)". Archived from the original on 9 July 2011. Retrieved 29 June 2005.

- Rebecca Soraya Leake (July 2009). "Pulau Putri: Kebudayaan Migrasi dan Dampaknya di Pulau Bawean" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Pertanian di Bawean Terancam Puso" (in Indonesian). Media Bawean. 11 March 2010. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, 2021.

- "Bawean". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Airport to be Built on Bawean Island". Indonesia Tourism News. 29 July 2006. Archived from the original on 7 June 2015. mirror Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Persatuan Bawean Singapura" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 25 July 2011.

- "Orang Bawean di Singapura" (in Indonesian). 20 April 2010. Archived from the original on 11 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Bawean". Archived from the original on 11 January 2005. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Bawean" (in Russian). Brockhaus and Efron Encyclopedic Dictionary. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Pulau Bawean".

- "Sejarah Pengadilan Agama Bawean" (in Indonesian). Media Bawean. 7 July 2008.

- "Antara Surakarta dan Pulau Bawean" (in Indonesian).

- "Kubur Syech Maulana Umar Mas'ud" (in Indonesian). 1 June 2008. Archived from the original on 5 November 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "The First Fleet of the Dutch". Archived from the original on 13 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "1670 to 1800: Court Intrigues and the Dutch". Archived from the original on 15 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Sejarah Hutan Lindung Bawean" (in Indonesian). 27 October 2008. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "World War II Pacific". Archived from the original on 8 September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "U.S.S. John D. Edwards (216)". Archived from the original on 19 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Indonesian States 1946–1950". Ben Cahoon. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Всемирная история (in Russian). Vol. 12. M.: Мысль. 1979. pp. 356–359.

- K. Pimanov. "Indonesia" (in Russian). Encyclopedia Кругосвет. Archived from the original on 6 February 2009. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Peta Wisata Gresik" (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 12 January 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Lake Kastoba". Archived from the original on 13 July 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- Blouch, R. & Sumaryoto, A. (1979). Proposed Bawean Island Wildlife Reserve management plan. Bogor: WWF-Indonesia. p. 63.

- "Tanggapan Bencana Gerakan Tanah di Puiau Bawean, Kab. Gresik, Jawa Timur" (in Indonesian). 13 March 2008. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011.

- "Warga Bawean Shalat Menghadap ke Afrika" (in Indonesian). 26 July 2010. Archived from the original on 7 July 2011.

- "Bintang Putih Membuat Bawean Terkenal" (in Indonesian). 16 August 2010. Archived from the original on 14 March 2012. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Gresik Selayang Pandang" (in Indonesian). 16 November 2009. Archived from the original on 28 August 2010. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Indonesia launches tender for 26 oil and gas blocks". Thomson Financial. 30 October 2007. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015 – via MarineLink.com.

- "East Java HD-MC3D Seismic Survey" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Axis kuhlii". IUCN.

- Taufik, A.W. (1989). Pulau Bawean, Indonesia. In: Scott, D.A. (Ed.), A directory of Asian wetlands. Bogor: IUCN, The World Conservation Union. pp. 1024–1025. ISBN 2-88032-984-1.

- "Kecamatan" (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kabupaten Gresik. Archived from the original on 27 October 2010.

- Biro Pusat Statistik, 2011.

- "Pulau Bawean Belum Bisa Memiliki Rumah Sakit" (in Indonesian). Media Bawean. 22 December 2009. Archived from the original on 12 May 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "KONI Gresik Melantik Pengurus KONI Sangkapura" (in Indonesian). Media Bawean. 13 May 2010. Archived from the original on 16 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Kondisi Jalan Lingkar Pulau Bawean Bagian Barat" (in Indonesian). Media Bawean. 23 January 2010. Archived from the original on 5 September 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Bawean, Pulau Berselimut Damai" (in Indonesian). 21 May 2010. Archived from the original on 26 November 2010.

- "Gambaran Umum Kondisi dan Permasalahan" (in Indonesian). Pemerintah Kabupaten Gresik. Archived from the original on 11 January 2011.

- "Two Airlines ready to serve to/from Bawean Airport". 10 February 2013. Archived from the original on 28 December 2014. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- Abd Aziz (27 January 2014). "Lapangan terbang Bawean siap dioperasikan Juni 2014". Archived from the original on 31 January 2014. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "Lapangan Terbang Bawean Dijadwalkan Tahun Ini Beroperasi". 27 January 2015. Archived from the original on 29 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Badan Pusat Statistik, Jakarta, 2021.

- Madura: A language of Indonesia (Java and Bali) Archived 22 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Ethnologue

- "Roti Boyan (Bawean)" (in Indonesian). 2 May 2009. Archived from the original on 23 August 2011. Retrieved 24 October 2010.

- "Roti Boyan" (in Indonesian). 26 August 2008. Archived from the original on 15 July 2011.

Further reading

- Blouch, R. & Sumaryoto, A. (1978). Preliminary report of the status of the Bawean deer Axis kuhli. In: Threatened deer, proceedings of a working meeting of the Deer Specialist Group. IUCN, Morges.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Blouch, R. & Sumaryoto, A. (1979). Proposed Bawean Island Wildlife Reserve management plan. WWF-Indonesia, Bogor.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Blower, J.H. (1975). Report on a visit to Pulau Bawean. UNDP/FAO Nature Conservation and Wildlife Management Project INS/73/013. Field Report. FAO, Bogor.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hoogerwerf, A. (1966). Notes on the island of Bawean, with special reference to the birds. Natural History Bulletin of the Siam Society, Vol. 21. Bangkok.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)