Brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome

Brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome (BAOS) is a pathological condition affecting short nosed dogs and cats which can lead to severe respiratory distress. There are four different anatomical abnormalities that contribute to the disease, all of which occur more commonly in brachycephalic breeds: an elongated soft palate, stenotic nares, a hypoplastic trachea, and everted laryngeal saccules (a condition which occurs secondary to the other abnormalities). Because all of these components make it more difficult to breathe in situations of exercise, stress, or heat, an animal with these abnormalities may be unable to take deep or fast enough breaths to blow off carbon dioxide. This leads to distress and further increases respiratory rate and heart rate, creating a vicious cycle that can quickly lead to a life-threatening situation.

Brachycephalic dogs have a higher risk of dying during air travel and many commercial airlines refuse to transport them.[1][2]

Dogs experiencing a crisis situation due to brachycephalic syndrome typically benefit from oxygen, cool temperatures, sedatives, and in some cases more advanced medical intervention, including intubation.

BAOS is also referred to as Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome (BAS), Brachycephalic Syndrome (BS),[3] and in the UK as Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS).[4]

Causes and risk factors

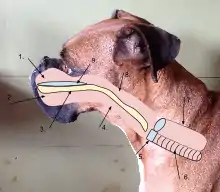

1. Nasal cavity 2. Oral cavity 3. Soft palate 4. Pharynx 5. Larynx 6. Trachea 7. Esophagus 8. Nasopharynx 9. Hard palate

The brachycephalic dog has a shorter snout which causes the airway to be shorter, that means all the parts that make up the airway get pushed closer together. Due to this phenomenon, a brachycephalic dog has an elongated soft palate which can cause most of the problems with the dog's breathing. They can also have problems getting enough air in because of their elongated soft palate and shorter airway.

The primary anatomic components of BAOS include stenotic nares (pinched or narrowed nostrils), and elongated soft palate, tracheal hypoplasia (reduced trachea size), and nasopharyngeal turbinates.[3]

Other risk factors for BAOS include a lower craniofacial ratio (shorter muzzle in comparison to the overall head length), a higher neck girth, a higher body condition score, and neuter status.[5]

Recent studies led by the Roslin Institute at the University of Edinburgh's Royal School of Veterinary Studies has found that a DNA mutation in a gene called ADAMTS3 that is not dependent on skull shape is linked to upper airway syndrome in Norwich Terriers and is also common in French and English bulldogs. This is yet another indication that at least some of what is being called brachycephalic airway syndrome is not linked to skull shape and has previously been found to cause fluid retention and swelling [6]

Signs and symptoms

%252C_February_2010.JPG.webp)

- Dyspnea (breathing difficulty)

- Noisy/labored breathing

- Stridor (high pitched wheezing)

- Continued open-mouth breathing

- Extending of head and neck to keep airway open

- Sitting up or keeping chin in an elevated position when sleeping

- Sleeping with toy between teeth to keep mouth open to compensate for nasal obstruction[7]

- Cyanosis (blue/purple discoloration of the skin, due to poor blood oxygenation in the lungs )

- Sleep apnea

- Stress and heat intolerance during exercise.

- Snoring, gagging, choking, regurgitation, vomiting

- Collapse

Symptoms progress with age and typically become severe by 12 months.[7]

Despite observing clinical signs of airway obstructions, some owners of brachycephalic breeds may perceive them as normal for the breed, and may not seek veterinary intervention until a particularly severe attack happens.[8][9]

After waking from surgery, most dogs that are intubated will try to claw out their tracheal tube. In contrast, brachycephalic dogs often seem quite happy to leave it in place as it opens the airway, making it easier to breathe.[10]

Secondary conditions

Other conditions may be observed concurrently. These include swollen/everted laryngeal saccules, which further reduce the airway, collapsed larynx, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease caused by the increased lung workload.

Brachycephalic syndrome has been linked to changes in the lungs, as well as the gastrointestinal tract including bronchial collapse, gastroesophageal reflux, and chronic gastritis.[11]

Diagnosis

This syndrome is diagnosed on the basis of the dog's breed, clinical signs, and results of a physical examination by a veterinarian. Stenotic nares can usually be diagnosed on visual inspection. Diagnosis of an elongated soft palate, everted laryngeal saccules, or other associated anatomical changes in the mouth will require heavy sedation or full general anesthesia.[11]

Treatment

Treatment consists of surgery for widening the nostrils, removing the excess tissue of an elongated soft palate, or removing everted laryngeal saccules. Early treatment prevents secondary conditions from developing.

Potential complications include hemorrhages, pain, and inflammation during and after surgery. Some veterinarians are hesitant to perform soft palate correction surgery. With CO2 surgical lasers, these complications are greatly diminished.[12]

Prevention

Avoiding stress, high temperatures, and overfeeding can reduce the risk. Using harnesses instead of collars can avoid pressure on the trachea.

The risk of brachycephalic syndrome increases as the muzzle becomes shorter.[5] To avoid producing affected dogs, breeders may choose to breed for more moderate features rather than for extremely short or flat faces. Dogs with breathing difficulties, or at least those serious enough to require surgery, should not be used for breeding.[13] Removing all affected animals from the breeding pool may cause some breeds to be unsustainable and outcrossing to non-brachycephalic breeds might be necessary.[14]

Although outcrossing can attempt to lengthen the average snout length within a breed over time and reduce BAOS, it is not popular with established breed registries who record pedigrees of purebred dogs. In 2014, the Dutch government passed the Animals Act and the Animal Keepers Act, and subsequent enforcement caused the Dutch Kennel Club (Raad van Beheer) in 2020 to announce they were restricting registrations within 12 dog breeds based on snout length, and encouraging outcrosses to other breeds, while promising that future generations may be eligible for registration as purebreds. This caused concern with the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI), of which RvB is a member, and with the American Kennel Club, both of which expressed concerns about governments legislating such matters.[15][16][17]

Other health problems

Non-airway problems associated with brachycephalia may include:

- Inflammation in skin folds

- Mating and birthing problems

- Malocclusion – misalignment of the teeth.

- Dental crowding

- Brachycephalic ocular syndrome[14]

- Ectropion/entropion – inward/outward rolling of eyelid

- Macropalpebral fissure

- Lagophthalmia – inability to close eyelids fully

- Exophthalmos/eye proptosis – abnormal protrusion of the eye

- Nasal fold trichiasis – fur around the nose fold rubs against the eye.

- Distichiasis – abnormally placed eyelashes rub against the eye.

- Poor tear production

- Gastrointestinal problems[18]

See also

- Cephalic index – for lists of affected dog, cat, and other animal breeds

References

- Gay, Lisa (April 24, 2019). "Taking Your Dog on a Plane Just Got Harder". New York Times. Archived from the original on April 24, 2019.

- "Air travel and short-nosed dogs FAQ". American Veterinary Medical Association.

- "Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome (BAS)" (PDF). University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine. October 4, 2017.

- "About BOAS". Cambridge Veterinary School. February 16, 2016.

- Packer, RMA; Tivers, MS; Hendricks, A; Burn, CC (2013). Short Muzzle; Short Of Breath? An Investigation Of The Effect Of Conformation On The Risk Of Brachycephalic Obstructive Airway Syndrome (BOAS) In Domestic Dogs (PDF). UFAW Symposium, Barcelona. Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. Retrieved 21 January 2018.

- "Dog DNA find could aid breathing problems".

- Roedler FS, Pohl S, Oechtering GU (December 2013). "How does severe brachycephaly affect dog's lives? Results of a structured preoperative owner questionnaire". Veterinary Journal. 198 (3): 606–10. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.009. PMID 24176279.

- "Worrying numbers of "short-nosed" dog owners do not believe their pets to have breathing problems, despite observing severe clinical signs". The Royal Veterinary College. 10 May 2012. Retrieved 29 June 2013.

- Packer RM, Hendricks A, Burn CC (2012). "Do dog owners perceive the clinical signs related to conformational inherited disorders as 'normal' for the breed? A potential constraint to improving canine welfare". Animal Welfare. 21: 81–93. doi:10.7120/096272812X13345905673809.

- Johnson T. "Breathless: Bulldogs, pugs need protection from the heat". Veterinary Information Network. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Brachycephalic Airway Syndrome in Dogs". vca_corporate. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- Arza R (2016-09-29). "Elongated soft palate resection with a CO2 surgical laser". Aesculight. Retrieved 2017-02-06.

- "Brachycephalic syndrome". Canine Inherited Disorders Database. Archived from the original on 7 September 2013. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- "Shih Tzu: Brachycephalic Ocular Syndrome". Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. 2011. Retrieved 2017-11-25.

- Jakkel, Dr. Tamás (May 20, 2020). "Open letter from the FCI President about the matter of the registration of brachycephalic breeds in the Netherlands". Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- "The current position of the short-muzzled dog breeds in the Netherlands and what preceded it" (PDF). Dutch Kennel Club Raad van Beheer. 25 May 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- AKC Government Relations Department (June 5, 2020). "AKC Statement on Dutch Kennel Club 'Brachycephalic Decision: Context and a Cautionary Tale". American Kennel Club. Retrieved August 27, 2021.

- Poncet CM, Dupre GP, Freiche VG, Estrada MM, Poubanne YA, Bouvy BM (June 2005). "Prevalence of gastrointestinal tract lesions in 73 brachycephalic dogs with upper respiratory syndrome". The Journal of Small Animal Practice. 46 (6): 273–279. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2005.tb00320.x. PMID 15971897.