Bromyard

Bromyard is a town in the parish of Bromyard and Winslow, in Herefordshire, England, in the valley of the River Frome.[2] It is near the county border with Worcestershire on the A44 between Leominster and Worcester. Bromyard has a number of traditional half-timbered buildings, including some of the pubs; the parish church is Norman. For centuries, there was a livestock market in the town.

| Bromyard | |

|---|---|

View of Bromyard from Bromyard Downs | |

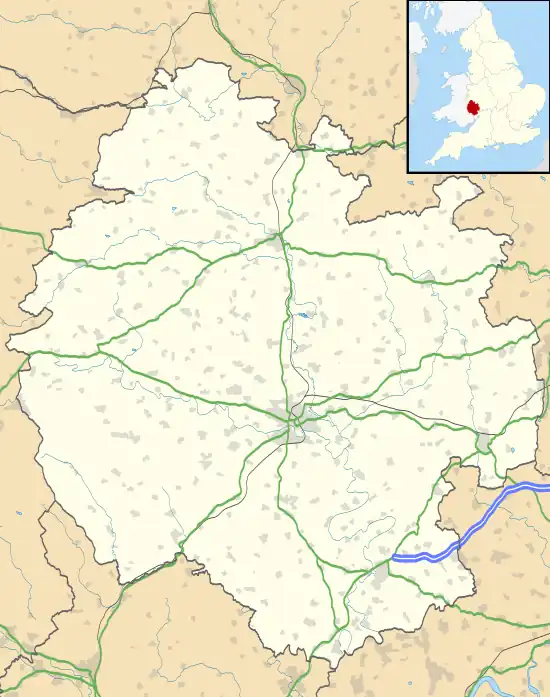

Bromyard Location within Herefordshire | |

| Population | 4,500 [1] |

| OS grid reference | SO654548 |

| Civil parish |

|

| Unitary authority | |

| Ceremonial county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | BROMYARD |

| Postcode district | HR7 |

| Dialling code | 01885 |

| Police | West Mercia |

| Fire | Hereford and Worcester |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

History

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Bromyard is mentioned in Bishop Cuthwulf's charter of c. 840.[3] Cudwulf established a monasterium at Bromgeard behind a 'thorny enclosure' with the permission of King Behrtwulf, King of the Mercians. Ealdorman Aelfstan, the local magnate, was granted between 500 and 600 acres of land for a villa beside the River Frome.[4] The settlement in the Plegelgate Hundred was allocated 30 hides for 'the gap [in the forest] where the deer play.' The county court assembly was on Flaggoner's Green, now a hill in the modern borough and where the cricket club is situated.[5] 42 villani (villeins, villagers), 9 bordars (smallholders), and 8 slaves were recorded in the Domesday Book entry in 1086, one of the largest communities in Herefordshire.[6]

The first mention of the spelling "Bromyard" was in Edward I's Taxatio Ecclesiasticus on the occasion of a perambulation of the forest boundaries to set up a model for Parlements in 1291. It began to appear regularly in the church and court records of the 14th century.[7]

Like Leominster, Ledbury, and Ross-on-Wye, the town and fair at the manor of Bromyard was probably founded in c1125 during the episcopate of Richard de Capella (1121–1127).[8] As with those other three towns, the bishops of Hereford had had a manor and minster there since Anglo-Saxon times. As at Ledbury the church was collegiate, with an establishment of clergy known as "portioners", but without a master and common seal.[9] Surveys for the bishop made c. 1285 and 1575-80 give valuable information about the town's first few centuries.[10] Bromyard contained 255 burgage and landowner tenancies in the 1280s which paid a total rent of £23 10s 7 1/2d to the bishop. A Toll Shop at Schallenge House ("Pie Powder" from pieds a poudre) was where market tolls were paid and summary jurisdiction dealt out.[11]

After the Reformation (1545) there were 800 communicants making Bromyard then "a markett toune...greately Replenyshed with People", the third town in the county with a population of about 1200 souls.[12] By 1664 Bromyard had fallen behind Leominster, Ledbury and Ross in population.[13] Besides the central town area, the large parish used to consist of the three townships of Winslow, Linton, and Norton; these areas were civil parishes in the 20th century.[14]

During the civil wars, Prince Rupert's troops in March 1645 "brought all their [power] on Bromyard and Ledbury side, fell on, plundered every parish and house, poor as well as others, leaving neither clothes nor provision, killed all the young lambs in the country, though not above a week old.[15] Charles I stayed the night in Bromyard at Mrs Baynham's house (now Tower House) on 3 September 1645 on his way to Hereford[16] In 1648, Parliament ordered the sale of the cathedral's property in Bromyard Forrens (i.e. outside the borough) for £594 9s 2d.[17]

Bromyard Grammar School was re-founded in 1566 after the original chantry endowments had been nationalised. In 1656, the City of London Alderman John Perrin, from Bromyard, left the school £20 per annum, to be paid through the Goldsmiths Company. The company improved the school buildings in 1835. The building still stands in Church Street, but the school became part of the first comprehensive school in Herefordshire in 1969, now known as Queen Elizabeth High School.[18] A Congregational Chapel was built in 1701.[19]

Commercial centre

For centuries, market day was always held on a Monday at Bromyard.[20] The market town was a centre for agriculture with a fair for selling produce grown locally; as well as beef, there were hops, apples and pears, and soft fruit remained vital late into the post-war era.[21] Some farms remained in the church's hands until the late 20th century.[22] The carrier system also operated in Bromyard, within a given radius of the Teme to the north, Frome Hill to the east, and Lugg to the south. The dealers brought supplies to the many outlets, pubs, inns, traders and by the 19th century the shops.[23]

In 1751, Bromyard obtained a Turnpike Trust that established a toll road as far as Canon Frome, with some minor roads turnpiked to prevent tax evasion. By 1830 town's fortunes had flagged down to only fifth in the county from second 300 years before; its stage wagons visited only 15 times per week. This reflected its place in the Industrial Revolution which came very late to Bromyard, partly because it took so long to connect the town to the railway system. A sandstone quarry was opened at Linton, just east of the town, in the 1870s, but the hopes for extensive sales of good quality building stone were disappointed and by 1879 it was producing bricks and tiles from the Old Red Sandstone marls. This business continued until the 1970s.[24]

The town's water supply and sanitation was very poor until late in the 19th century; Benjamin Herschel Babbage conducted an inspection in 1850 (as he had the same year for the West Yorkshire town of Haworth). Babbage was horrified by the unsanitary conditions in the town, and reported to the General Board of Health into the town's water supply and lack of a sewerage system. He said that he had "met with considerable opposition to the application of the Public Health Act to this town, from a large number of the inhabitants, upon the ground of the supposed expense of carrying out the sanitary reforms which I found to be so much needed." No action was taken by the town vestry for over twenty years. The town belatedly acquired a piped water supply in 1900.[25]

During World War I, Bromyard was the site of an internment camp, where the Irish nationalist Terence MacSwiney (future Lord Mayor of Cork who would die on hunger strike), was both interned and married.[26]

In World War II, between autumn 1940 and 1945, Westminster School was temporarily relocated to a variety of buildings on the outskirts of the town, principally Buckenhill, and including, for various purposes, Brockhampton, Clater Park, Whitbourne Rectory and Saltmarshe Castle.[27]

From the 1950-60s, the town underwent substantial housing development, including both private and council housing, and shops along the high street flourished serving both Bromyard and surrounding rural communities. A bypass was built and completed in the 1970s to stop traffic along the A44 between Worcester and Leominster having to pass through the town. A community centre, including a public library and leisure centre was opened in the 1990s.

Governance

There are two electoral wards, Bromyard West and Bromyard Bringsty. The latter includes several villages to the north east. Bromyard borough has a town council. Herefordshire Council is a unitary authority.

| General Election 2015 : North Herefordshire Constituency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Liberal Democrats | Labour | UKIP | Green | Maj. | Turnout | |

| 26,716 55.6% |

6,720 14.0% |

5,768 12.0% |

5,478 11.4% |

3,341 7.0% |

19,996 41.0% |

42,545 72.0% | |

| General Election 2017 : North Herefordshire Constituency | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative | Labour | Liberal Democrats | Green | Maj. | Turnout | ||

| 31097 62.0% |

9495 18.9% |

5874 11.7% |

2771 5.5% |

21602 43.1% |

50293 74.1% | ||

Bromyard is one of three market towns (Leominster, Bromyard and Ledbury) in the parliamentary constituency of North Herefordshire. The current member as of the snap general election of 2017 is Conservative Bill Wiggin MP.

Bromyard is served by the Bromyard and Winslow Town Council which has three clerks and a Mayor. It has 18 councillors who are predominately independent[29]

Bromyard and Winslow is a civil parish in Herefordshire.[30] According to the 2001 census it had a population of 4,144, increasing to 4,236 at the 2011 census.[31] The parish contains the town of Bromyard, and Winslow which is a sparsely populated rural area to the west.[32] In 2014 the population was estimated to have risen to 4,600, and increase of about 200 or 4.5%, and 2% higher than the county's average.[33] In 2015 a national influenza and pneumonia epidemic meant that the birth and death rate almost reached parity causing a slow down in the town's population growth.[34] The town centre is considered among the 25% most deprived in the country for older people, irrespective of its relatively low population density.[35]

Bromyard is a former civil parish. In 1961 the parish of Bromyard had a population of 1680.[36] On 1 April 1986 the parish was abolished and merged with Winslow to form "Bromyard & Winslow".[37]

Culture

The Bromyard & District Local History Society was founded in 1966, with a centre open three days a week which contains an archive, library and an exhibition room.[38]

The Conquest Theatre (run by volunteers) provides a programme of plays, films, variety, musicals, operettas, ballet, pantomime and concerts in a purpose-built centre constructed in 1991.[39]

The Time Museum of Science Fiction is in the centre of Bromyard, housing exhibits from TV programmes including Dr Who, Red Dwarf and Thunderbirds, as well as props from the Star Wars films.[40]

Bromyard Arts is a not-for-profit enterprise with facilities for artists, craft makers, writers, musicians and performers.[41]

At Christmas time, volunteers known as the Bromyard Light Brigade organise a display of Christmas lights which are put up in October and switched on the last Saturday of November, running for the five weeks up to Christmas until after the New Year. The group established links with Blackpool Illuminations in 2010, and Blackpool's director Richard Ryan performed the switching-on ceremony in the same year; the volunteers were awarded The Queen's Award for Voluntary Services that same year.

Bromyard is the home of "Nozstock: The Hidden Valley Festival", which attracts around 5,000 visitors at the end of July every year. This three-day event showcases bands from around the country across nine stages, alongside dance arenas, a cinema, a theatre and comedy stage, circus, and a vintage tractor arena.[42]

The Bromyard Gala, an annual weekend festival of country sports, vintage vehicles and displays of various kinds, is held in July.[43]

Bromyard holds a three-day folk festival each year in September, which particularly concentrates on English traditional music.[44]

Sports

Sports clubs in Bromyard include Bromyard Town F.C. who are currently members of the West Midlands (Regional) League Division One and play at Delahay Meadow; Bromyard Cricket Club that play at Flaggoners Green, whose three senior sides play in the Worcestershire County Cricket League (WCL). Their 1sts are in the Worcestershire Premier Division which acts as a feeder into the Birmingham League; and Bromyard Rugby Club based at the Clive Richards Sports Ground, with senior men's and ladies teams, and junior teams.

Transport

.jpg.webp)

The Worcester, Bromyard and Leominster Railway, now dismantled, was first proposed in 1845, and an Act of Parliament to build it obtained in 1861. Estimated to cost £20,000, that number of £10 shares were issued. When sold to the Great Western Railway in 1887, the shares were only worth ten shillings.[45] The line had only arrived from Worcester in 1877, but it was already 3.5 miles to the east at Yearsett. It was not until 1897 that an onward connection was made to Leominster.[46] It was a common destination for 'hop-pickers' specials' from the Black Country.[47] There were five trains a day in each direction. The line to Leominster was closed in 1952, the last train ran in 1958, and the line, closed due to financial instability, became a victim of the Beeching cuts in 1963–4.[48] For a short time the section between Bromyard and Linton was run as a private light railway – the Bromyard and Linton Light Railway – which still exists, albeit now disused.[49]

Bromyard is the starting place of the A465 road which terminates at junction 43 of the M4 motorway at Llandarcy in South Wales. The town centre is bypassed by the A44 road that connects Aberystwyth to Oxford. Bromyard is notable for its many old and historically interesting buildings that are designated blue plaque buildings, especially in High Street, Broad Street, Market Square, Sherford Street and Rowberry Street, including a number of half-timbered public-houses and dwelling houses.

Architecture

St Peter's, Bromyard

_(19144499556).jpg.webp)

_(19144496636).jpg.webp)

_(18550027553).jpg.webp)

_(19170646955).jpg.webp)

_(18982976400).jpg.webp)

St Peter's Church is a large cruciform building described in 1574 "with many cathedral churches no fairer" with parts dating back to Norman times, including an effigy of St. Peter, with two keys, over the main (reset) Norman south doorway.[lower-alpha 1] Most of the exterior is early 14th century.[50] An Anglo-Saxon minster church existed before the present St Peter's Church. No physical remains survive, but the minster and manor are mentioned in a document of 840 AD.[51] Inside the largely 14th century church lies a Norman font. The common element to the design was Y-shaped tracery throughout, chamfered roof beams of timber. The Norman nave was marked by capitals in the Decorated Style with lozenges, rosette and chevron. There was a genuine Tympanum in the north transept. The chancel was restored in the 14th century with ubiquitous window tracery. The oldest part of the church, the south arcade may have been built in the reign of Richard the Lion Heart, when Norman knights began to build churches in the county.[lower-alpha 2] The columnaded north arcade was built under King John characterised by leaf crockets, quatrefoils, and double-chamfered beams.

Bromyard church was early favoured by generous benefactors, as the Hereford Red Book of the Exchequer testified in 1277. The Lancastrian knights Sir John Baskerville and Sir Hugh Watcham donated two chantry chapels; with an unusual lavacrum in the south transept. At about the same time a Ricardian founded a chantry school for the parish, which was saved at the reformation on appeal in 1547 after 150 years of existence. Of the 17 grammar schools in the county only four survived the suppression of the monasteries, reflecting directly future development of the towns.[52] Bromyard borough was the second town in Herefordshire owing to the woollen trade, but was taxed and chantries confiscated by the Crown under Queen Elizabeth I.[53]

After the English Civil Wars the church fell into near fatal dilapidation for about a century. Much of the church was substantially restored by the Victorian architect Nicholson and Sons to the transepts in 1887, and the stalls beneath the tower, revealing the roof clerestory. A war memorial was added in 1919. Thus was followed by extensive repairs to the stained glass in the 1930s by A J Davies and later by A K Nicholson. Inside the church monumental slabs litter the chancel walls with worthies of Bromyard: John Baynham (1636), Thomas Fox (1728), Laetitia Pauncefoot (1753), Roger Sale (1766), Joseph Sterling (1781), Bartholomew Barneby (1783), James Dansie (1784), Roger Sale (1786), Abigail Barneby (1805), Edward Moxam (1805). At the Millennium the churchyard was cleared of monumental inscriptions.[54]

Winslow

The civil parish of Winslow was a total 2,854 acres (1,155 ha) in the original township devolved from the Saxon parochia.[55] To the west stands two outstanding Georgian properties. The Green was a large farm on which a big house was built in 1770 for Thomas Colley owned the smart three-storey house with a brick facade in 1771 two miles west of Winslow Township. A plan was drafted by 1780, owned 114 acres (46 ha) of which nearly half was meadow. It consisted of 5 bays with pedimnented centre and doorways of tripartite Doric columns. Typical of the Decorated Style, the blank sections on the wall offset the elaborations. Colley also installed Venetian windows and a baluster staircase. Obvious bays contrasted with fronted ornate pedimented doric columns at the entrance. Venetian windows hint at the Georgian Grand Tour and the ornate style architecture typical of the county. It also contains a remarkable baluster staircase. In horse country it was usual to have outbuildings and stables made of stone.[56] There was a blacksmith's smithy nearby next to 21 acres (8 ha) of woodland.

A farm of 110 acres existed at Hardwick Manor. This was named for Anthony Hardwick in 1575 when he purchased the freehold. His descendant, John, fell into debt and in 1755 was forced to sell Hardwick Hall, which was demolished, and the rest of the estate was sold to Thomas Griffiths of Stoke Lacy. The manor house was rebuilt on the site.[57]

Medieval Munderfield was settled by a lesser Norman gentry family named D'Abitot.[58] Mundersfield Harold is an even earlier Augustan era mansion made of brick on an H-Plan with typical bays and hipped roofs. There is a Venetian staircase, plaster mouldings, and a glazed porch. In the Victorian period a south wing with a terracotta balustrade was added. The estate had extensive farm buildings to the north-west, these were laid out, which was then followed by a large landscaped park. The house acquired a lodge in the 1880s facing a main road. There were three well-appointed farmhouses in the Norton area by 2000. The Lower Norton property of Hill Farm was built in the late 18th century with a barn of timber-framing alongside.

In the 21st century Winslow parish was once again merged into Bromyard Town borough due to urban developments.[59]

Bredenbury

Although Wacton Court no longer exists, Wacton Farm was part of the same estate. It was purchased by Richard Hardwick in 1720, and two houses in Bromyard, which were let. A hall was founded at Lower Hardwick in the Tudor period with bays, studding, and diagonal cross-bracing. A new wing was added on the north-western side in the Jacobean era. Gabled windows are distinguished by the lozenges with elaborate carved mouldings on diagonal wooden dragon-beams in the roof with supporting columns. There was a hop farm at Wicton with three large square kilns.[60]

The main building was a stone house, Bredenbury Court built for William West in 1809 and then remodelled for the Barnebys by A.T.Wyatt in 1873–4. The red-rock faced Italianate Neo-Elizabethan mansion had a number of bays before additions in 1898 by a new owner Francis Greswolde-Williams. The architect Guy Dawber was instrumental in much of the current improvements: a west end extension, rusticated corner pilasters, and open pediments. The east wing dated after the 18th century architect James Gibbs with fine plaster work and a Wyatt staircase with twisted balusters. St Richards Prep School added a north-west brick classroom in 1924. The lodges belonged to Wyatt in picturesque gabled Gothic; but the stables were Dawber's work in 1902. William Harington Barneby laid out the grounds with formal gardens and shrubberies to a design by Edward Milner of Sydenham, Kent.[61]

The medieval parish church was rebuilt by the High Victorian W.H. Knight in 1861–2, only to be demolished a decade later. A new church on a new site was built to T H Wyatt's design in 1876–7 to replace Wacton Church and Old Bredenbury. The font was imported from Wacton, as was some of the stained glass windows. Ashlar dressings and fish-scale tiles were decorated in the 14th century new-medieval style. The beautiful interior was sumptuously appointed with marble alabaster tombs, fittings and reredos. A chancel was added in 1880 and a pulpit two years later. Ornate carving from R.L. Boulton was matched by Lavers stained glass which took ten years (1877–87) to complete.

Rowden

The 465 acres of land area in Rowden (meaning a rough hill) was occupied by Sir John la Moigne in 1300 when he built the first chapel there. The house was named after the ancient Rowdon family of Burley Gate, who occupied it during the English Civil Wars. Edward Rowden built a new house in 1651 on the ruins of the medieval buildings; its dovecote was a local landmark of "circular stone". It was unoccupied by 1721.

Rowden House was formerly known as Rowden Barn in the 1830s. It was a large stone building erected by judicious marriage into the family of Warren Hastings, the Governor-General of India. Rowden House was rebuilt in 1883, for a son of Lord St John cut out of stone after the Queen Anne-style, with a hipped roof and noteworthy pedimented dormer window.[62] The brick chimneys, medallion cornices, and keystoned arches are from an earlier era. Like other Grade 1 listed buildings in the district it is busied by ornate carving, lozenges, and carved roof-beams. The estate was owned by the industrialist John Arkwright who was responsible for the addition of unusually decorated farm cottages built in 1867. Rev W N Berkeley the local rector resided there in 1891, but it was sold to Rear-Admiral J Alleyne Baker in 1909. The owners sported a fine ballroom popular with local people.

The original medieval moated abbey beside the River Frome was demolished in about 1790. The present Rowden Abbey was rebuilt in 1881 as a half-timbered mansion for landowner Henry J Bailey.[63] Similar to the above houses in style and decoration, it also exhibited fine gabled porch entrances. The interior had panelling and ribbed ceilings, with delightful bay windows in the reception rooms.

Rowden Mill was a late Elizabethan/early Jacobean converted stone and timber house along the banks of the River Frome. The mill was a three-storey working building with a timber-framed dwelling house attached. On one side of it stood the mill and on the other a bakery and house, which continued as a Master Bakery until 1945. It was for centuries a working corn mill grinding the grain on the Rowden estates. However, by the 20th century it faced economic decline; yet E Powell Tuck still made it a commercial operation during World War Two.

The Tack was probably a successful medieval sheep farm since the name is derived from the Anglo-Saxon tacca. A farmhouse stood on the Tenbury Road; built of stone in 1838 it contained a large hop kiln and granary in a complex of buildings, now part of the dwelling. Among its quirky features included two bays in a stable block once used as servants quarters that were built circa 1800.

Norton

The medieval manor of Norton in the Broxash Hundred, today in the adjacent parish of Norton at the north-east, was constrained by extensive parkland and hunting-grounds amounting a total of 3,183 acres.[64]

Peter de Newebond took occupation of Newbarns in about 1285 on half virgate of land at the same time that the Welsh Wars began. By the 16th century a fish pool had been established to provide food. During 1720s William Tarbox sold the properties to Packington Tomkins, who let it to tenant farmers. By 1850 it was a large three-storey house, a two bay wing, contained a household of 20 family and servants. The house had been brick rebuilt in 1800 incorporating some timber-framing. Both Tomkins and Higginson extended the house in the Victorian era before it changed hands again to a farmer in 1922.

The apple tree enclosure was the cultivated nature of Mapleton Barn when first settled in the late 13th century. A yeoman farmer took on the orchards, livestock in Jacobean period, but was merged by tenant farmer John Smith with Newbarns in 1777.

Three large blocks comprised The Rhea in 1838, the forerunner of a much larger complex in the late 20th century. In 1851 Thomas Gardiner farmed the land of 220 acres with 7 labourers. A brick house was built in 1900, with several 19th century workers stone cottages. A timber-framed stone barn was erected in the 18th century for a cow byre and stone stables.

On 'beech hill' in Elizabethan times Buckenhill Manor was recorded as two virgates. But during the early modern period a succession of different owners added farms and acreage to the estate. A Jacobean farmhouse was remodelled: the fine Georgian mansion at Buckenhill was inherited by Mrs Elizabeth Barneby, which unusually she passed to her daughter, Mrs Phillips. The house itself possessed 15 fireplaces, for the duration that royalist Barnebys owned it, but was later altered by an influential Bromyard propertied man Packington Tomkins.[65] Made of mellow brick and constructed in 1730, a 9 bay wing was added to face south; a string course on the first floor. The matching brick style encasing the older house of plasterwork and panelling meant the new and principal wing of the house would have pedimented gables, attics and cellars. The Victorian clock tower to the rear was erected in 1840 by Edmund Higginson. The landscape park was dug with a lake in place, damming the River Frome to create a garden oasis. Towards the Tenbury Road three attractive lodges were built in the late 19th century.[66]

Corinthian capitals atop decorated columns were in the same school as Inkberrow and Bromsberrow Place in the neighbouring county. The older east and front wings were made of stone; bent or chamfered roof beams vacated space in loft for living. Amongst the extensive stabling and outbuildings were hop kilns, a brewhouse, bakehouse and cider house, and octagonal dove cote. But the house was dilapidated by 1939 when occupied by the evacuated Westminster School.

Buckenhill Grange was a L-shaped 1750 farmhouse built in the Dutch style with gables out of coarse-hewn stone. On the west gable of this home farm was added a modelled barn with strong diagonal bracings. It had a granary below which was a cobble-stone farm yard for free-range hens. The Buckenhill Mill was acquired by purchase by Thomas Tomkins, son of Packington in 1728.

Brockhampton-by-Bromyard

Richard, son of Robert de Brockhampton was the first holder of the advowson of the chapelry in 1283. The main effect of the Black Death and end of serfdom was for the church to abandon the bishop's palace in the town, reaffirming the independency of the town's trading burgesses.[67] At the height of the town's influence, Dr Richard Pede DCL was a portionist at Bromyard. Becoming embroiled in national politics he joined the Yorkist rising at Hereford, being later appointed Vicar-general to the royal council at Ludlow Castle.[68]

Ownership passed thence to Thomas Solers, to Sir Thomas le Moigne, to the Rowdons of Burley Gate, the Habingtons, and by the Mid-Tudor era the Barnebys of Acton, County Wigorn (now modern Birmingham). The Barnebys remained one of the most influential families for the next 400 years in the district's development as a wool market, and significant centre of the wool trade for the Midlands. Richard Habington had acquired the lease of the manor of Bromyard in 1444.[69] Thomas Barneby was slain at Towton in 1461, and the family, firm Royalists were compounded by parliament after the Civil wars. One of the Barnebys, Edmund changed his name to Higginson to acquire Saltmarshe Castle, long associated with the Coningsbys of Hampton Court. The two families were closely inter-related by marriage. In 1872 the castle came down to Barneby-Lutley, another branch of the same medieval family.

Lower Brockhampton, a moated farmhouse on an extensive National Trust property, lies a short distance to the east, beyond Bromyard Downs. This is an area of common land lying to the northeast which offers many walks, with extensive views over the town, the Malvern Hills, the Clee Hills, and the Welsh borders, with the Black Mountains and other hills beyond. An attempt by local landowners in 1866 to enclose the Downs was strongly opposed by townsfolk and failed, not least because it was an area of recreation including rifle butts and an annual race meeting.[70]

Twin towns

Notable people

- Michael Cronin, cricketer

- Zahid Saeed, cricketer

- Garry Roberts, pop singer

- Thomas Winwood, cricketer

- Tommy Green, footballer

- Richard Pearsall, a churchman

- Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, royal favourite

- George Henry Evans, a radical

- Ronald Adam, actor

See also

Notes

- the St Peter's College, Oxford and St Peter's College, Radley include the important heraldry motif of St Peter's keys.

- see Brinsop Court

References

- "The Population of Herefordshire 2009" (PDF). Herefordshire Council. Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- "Census 2011". Archived from the original on 30 July 2012.

- HD and CM 4067; Hillaby & Pearson, Bromyard: A Local History, pl.1; Williams, Bromyard: minster, pl. 1

- OED: Brommgeard – "enclosure where broom or gorse grew" or perhaps "fenced in by gorse"; and in Domesday Book as Bromgerde, E. Ekwall, Oxford Dictionary of English Place-names; alternative local folklore tradition has it that Brom was synonymous with Frome.

- Williams, pg. 9

- "Domesday Book of William the Conqueror". Domesdaymap.co.uk. Retrieved 30 March 2020.

- Episcopei Registri (1363)

- Joe Hillaby, A Mediaeval Borough, (1997), pp.12–13

- Williams, Bromyard: Minster, Manor and Town, pg. 19

- A transcript of "The red book", a detailed account of the Hereford bishopric estates in the thirteenth century edited by A.T. Bannister, 1929; Swithun Butterfield's survey of the same in 1575-80 in Herefordshire archives

- Williams, op. cit. pg. 19

- chantry certificates, Hillaby, Ledbury, pg. 85

- Hearth Tax Returns 1664; Hillaby, Ledbury, pg. 90

- P. Williams, Bromyard: Minster, Manor and Town (1987)

- BL Harleian MS 1789; 'Certain Observations', f247r; David Ross, Royalist, But..., pg. 94

- HCRO, BC63/1;Ross, pg. 111

- Ross, pp. 158-159.

- Bromyard: A Local History, pp. 62-71

- Alan Brooks and Nikolaus Pevsner. Herefordshire (London 1938), pg. 36

- Pinches, pg. 44

- A Pocket Full of Hops, 1988, revised edition 2007, Bromyard & District Local History Society.

- Hillaby, Medieval Borough, pg. 32

- Pinches, pp. 55-59

- "Herefordshire through time". Archived from the original on 5 May 2015.

- "Joan Leese in Bromyard – a Local History", Bromyard and District Local History Society, (1970); Hillaby, Ledbury, pg. 127

- Journal of Bromyard and District LHS, no. 19, 1996/97.

- Journal of Bromyard & District LHS, no. 8 (1985).

- "Herefordshire North parliamentary constituency – Election 2019" – via www.bbc.co.uk.

- "Home". bromyardandwinslow-tc.gov.uk.

- Ordnance Survey: Landranger map sheet 149 Hereford & Leominster (Bromyard & Ledbury) (Map). Ordnance Survey. 2009. ISBN 9780319229538.

- "Civil Parish population 2011". Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- The Herefordshire Council have recently revised the 2011 Census totals to 4461 persons. Review the website: https://www.herefordshire.gov.uk/leisure-and-culture/local-history-and-heritage/archives-collections/herefordshire-population/#Hereford Archived 5 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- This was designated to be the parishes of Bromyard & Winslow and Avenbury. https://factsandfigures.herefordshire.gov.uk/media/48832/population-of-herefordshire-2016-v20.pdf

- "Home – Understanding Herefordshire". understanding.herefordshire.gov.uk.

- "2015 English Indices of Deprivation, Department of Communities and Local Government" (PDF). Retrieved 4 March 2019.

- "Population statistics Bromyard CP/AP through time". A Vision of Britain through Time. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- "Bromyard Registration District". UKBMD. Retrieved 23 August 2023.

- "Bromyard History Society".

- Conquest Theatre, conquest-theatre.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- "The time machine museum of Science Fiction". timemachineuk.com.

- "Bromyard Arts, Crafts, Music and Performing Arts". Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2020.

- "Nozstock: The Hidden Valley – Festival". Nozstock: The Hidden Valley Festival. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- Williams, pg. 59

- Bromyard Folk Festival, bromyard-folk-festival.org.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2009.

- Phyllis Williams, Bromyard, Minster, Manor, and Town

- R.Littlebury, Directory of Herefordshire (1877)

- Anthony J. Lambert, West Midland Branch Line Album, 1978; Keith M. Beck, The West Midland Lines of the G.W.R., 1983

- "Beeching Axe". Archived from the original on 27 January 2013.

- P.Crosskey, 'Roads and Railways', Bromyard: A Local History; Williams, p.58

- N. Pevsner, Herefordshire, Buildings of England, 1963; 2012, p.142-3

- Bromyard: Minster, Manor and Town, Phyllis Williams 1987;The Buildings of England, Herefordshire, Alan Brooks and Nicholas Pevsner, Yale, 2012

- Williams, p.62

- Swithun Butterfield Survey 1575–80; Williams, p.62

- Brooks & Pevsner, p.142-3

- Tithe Commissioners Report 1838; Williams, p.158-9

- Pevsner & Brooks, p.150

- Williams, p.138

- Robinson, p.57

- Brooks & Pevsner, p.151

- HCRO Title Deeds, Wicton Farm; Williams, 151; Brooks, p.151

- Brooks & Pevsner, p.123-4

- Pevsner & Brooks, Buildings Herefs, 2010

- Williams, p.163

- 1838, Tithe Map Survey; Williams, p.103

- Hearth Tax 1665

- Brooks & Pevsner, p.152

- Bannister, n137, p.156-7; Capes, n1, p.226-9; Hillaby (2003), p.98; Hillaby (1997), p.74

- Hillaby (2003), p.119

- Nashe, Worcestershire, vol.1, p.584; Robinson, p.52

- Berrow's Worcester Journal, 26 May and 6 October 1866

- "Mairie d'Athis-Val de Rouvre et sa commune (61430)". Annuaire-Mairie. 27 April 2023.

- Primary Sources

- HD and CM Hereford Dean and Chapter Muniments 4067

- BL Harleian MSS

- Collectanea Curiosa

- Certain Observations

- Secondary Sources

- Bannister, A.T. (1923). "A Descriptive catalogue of Manuscripts of St Katherine's, Ledbury". Transactions of Woolhope Naturalists Field Club.

- Brooks, Alan; Pevsner, Nikolaus (2012). The Buildings of Hereford: Herefordshire. New Haven and London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Eisel, J.; Shoesmith, R. (2003). Pubs of Bromyard, Ledbury and East Herefordshire.

- Hillaby, Joe; Pearson, E. (1970). Bromyard: A Local History.

- Hillaby, Joe (2003). St Katherine's Hospital, Ledbury. Ledbury.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Hillaby, Joe (1997). Ledbury: A Medieval Borough.

- Hopkinson, Charles (1985). Herefordshire Under Arms: A Military History of the County. Bromyard and District Local History Society.

- Kelly, Cherry (2005). Bromyard's Victorian Heritage. Bromyard and District Local History Society.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Leese, Joan (1970). "Bromyard – a Local History". Bromyard and District Local History Society.

- Pearson, E.D. (1993). Two Churches: Two Communities, St Peter's Bromyard and St James Stanford Bishop. The Bromyard & District Local History Society.

- Pinches, Sylvia (2009). Ledbury: a market town and its Tudor Heritage. London. pp. 55–59, 68, 88, 107, 112–3, 116–7, 120, 126, 156, 162.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Robinson, Rev.Charles J. (2001) [1872]. A History of the Mansions & Manors of Herefordshire. Hereford and London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Ross, David (2012). Royalist but...Herefordshire in the English Civil War 1640–51. Logaston. pp. 50, 94, 111–3, 158.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Frank Thorn; Caroline Thorn, eds. (1983). Domesday Book: Herefordshire. Chichester.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Williams, P. (1987). Bromyard: Minster, Manor and Town.

- Bromyard & District Local History Society (2007) [1988]. A Pocket Full of Hops. Bromyard.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)