Brucella ceti

Brucella ceti is a gram negative bacterial pathogen of the Brucellaceae family that causes brucellosis in cetaceans. Brucella ceti has been found in both classes of cetaceans, mysticetes and odontocetes.[1] Brucellosis in some dolphins and porpoises can result in serious clinical signs including fetal abortions, male infertility, neurobrucellosis, cardiopathies, bone and skin lesions, stranding events, and death.[1]

| Brucella ceti | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | |

| Phylum: | |

| Class: | |

| Order: | |

| Family: | |

| Genus: | |

| Species: | B. ceti Foster et al. 2007 |

| Binomial name | |

| Brucella ceti | |

Brucella ceti was first isolated in 1994 when an aborted dolphin fetus was discovered.[2] Only a small portion of those with Brucella ceti have overt clinical signs of brucellosis indicating that many have the bacteria and remain asymptomatic or overcome the pathogen. Serological surveys have shown that cetacean brucellosis may be distributed worldwide in the oceans. The likely transmission route for the bacterial pathogen in cetaceans is through mating or reproduction and lactation.[1] Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease: marine mammal brucellosis can infect other species, including human beings.

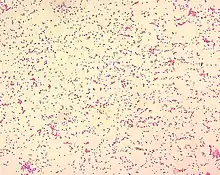

Bacterial Characteristics

B. ceti is a gram negative, non motile, aerobic bacteria. The cells are cocci, coccobacilli (short rods) with a diameter of 0.5–0.7 µm and a length of 0.6–1.5 µm. The arrangement of the cells are usually singular with occasional configurations in pairs or short chains. Cell growth occurs between 20 and 40 degrees celsius with the optimum temperature of 37 degrees celsius and is improved by the presence of blood or serum, supplemental CO2 is not required for cell growth. The ideal pH range is between 6.6 and 6.7.[3]

Host range

B. ceti has been found via PCR isolation in 4 out of 14 cetacean families but antibodies against the bacteria have been isolated in 7 families.[1] Within these families, B ceti has been cultured or found in Sowerby's beaked whales (Mesoploden bidens), longfinned pilot whales (Globicephala melas),[4] northern minke whales (Balaenoptera acutorostrata), Cuvier's beaked whale (Ziphius cavirostris), Atlantic white-sided dolphins (Lagenorhynchus acutus), harbor porpoises (Phocoena phocoena),[5] common dolphins (Delphinus delphis), white beaked dolphins (Lagenorhynchus albirostris), striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba), bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus)[6] Hector's dolphins (Cephalorhynchus hectori), Maui's dolphins (Cephalorhynchus hectori maui),[7] narwhales (Monodon monoceros), killer whales (Orcinus orca) and Southern right whales (Eubalaena australis)[8]

Clinical Signs

The most common symptoms include spontaneous abortions, fatigue, anorexia, seizures, fainting and neurobrucellosis, which can lead to disorientation and stranding events .[7] Other symptoms in dolphins from both the Pacific and Atlantic oceans include subcutaneous abscesses, endometritis, meningoencephalitis and discospondylitis.[9] Post mortem pathology studies on cetaceans also find inflammatory lesions, nodules of granulation tissues and necrosis in the heart, lungs and reproductive organs. In addition to this, it is common to find non lethal lesions in the bones and joints, which indicates a chronic presence of B. ceti in cetacean populations.[1] Only a small portion of infected individuals exhibit outwardly clinically or pathological signs.[1]

Diagnosis

Most cases of B. ceti have been isolated from stranded or dead cetaceans found on the coasts.[5] Diagnostic tests involve isolating the bacteria then completing direct identification methods to characterize the microorganism or indirect screening tests to find antibodies using serological tests.[1] In most cases B. ceti is detected by PCR amplification and DNA sequencing.[7]

Treatment

Captive dolphins with B. ceti have been treated with antibiotics, however, there has been no successful treatments for brucellosis documented in cetaceans.[8]

Transmission

B. ceti is a non-mobile bacteria, unable to withstand harsh conditions outside of a host.[5] It is shown to be transmitted both horizontally through social behavior and vertically from mother to fetus. It is passed through close contact between cetaceans through sexual intercourse, reproduction and aborted fetuses.[1] B. ceti has been found in reproductive organs and in milk produced by the host. Some cetaceans species assist others in giving birth and the bacteria could be contracted this way.[5] Transmission could also occur from feeding on fish infected with brucellosis through reservoirs that have the ability to replicate in cetaceans.[1]

Epidemiology

B. ceti has been found to be distributed worldwide, with the first case in the Mediterranean documented in 2012.[1] Brucellosis is a zoonotic disease that has many different strains pertaining to different host species.[5]

There have been four confirmed cases of humans becoming infected with marine mammal brucellosis. Cetacean specific brucellosis in humans may be underestimated in African, South American and Southeast Asian countries where humans frequently come in contact with dead cetaceans.[7]

History

Brucella ceti was first isolated in 1994 when an aborted dolphin fetus was discovered.[2] The first case of B. ceti infecting the reproductive organs was recorded in a California aquarium, where bottlenose dolphins experienced abortions. The bacteria was isolated from both the fetus and the placentas.[1]

References

- Guzmán-Verri C, González-Barrientos R, Hernández-Mora G, Morales JA, Baquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Moreno E (2012). "Brucella ceti and brucellosis in cetaceans". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 3. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00003. PMC 3417395. PMID 22919595.

- Garofolo G, Zilli K, Troiano P, Petrella A, Marotta F, Di Serafino G, Ancora M, Di Giannatale E (February 2014). "Brucella ceti from two striped dolphins stranded on the Apulia coastline, Italy". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 63 (Pt 2): 325–9. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.065672-0. PMID 24324028.

- Foster G, Osterman BS, Godfroid J, Jacques I, Cloeckaert A (November 2007). "Brucella ceti sp. nov. and Brucella pinnipedialis sp. nov. for Brucella strains with cetaceans and seals as their preferred hosts". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 57 (Pt 11): 2688–93. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.65269-0. PMID 17978241.

- Foster G, Whatmore AM, Dagleish MP, Baily JL, Deaville R, Davison NJ, Koylass MS, Perrett LL, Stubberfield EJ, Reid RJ, Brownlow AC (October 2015). "Isolation of Brucella ceti from a Long-finned Pilot Whale (Globicephala melas) and a Sowerby's Beaked Whale (Mesoploden bidens)". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 51 (4): 868–71. doi:10.7589/2014-04-112. PMID 26285099. S2CID 23666558.

- Guzmán-Verri C, González-Barrientos R, Hernández-Mora G, Morales JA, Baquero-Calvo E, Chaves-Olarte E, Moreno E (2012). "Brucella ceti and brucellosis in cetaceans". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 2: 3. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2012.00003. PMC 3417395. PMID 22919595.

- Maquart M, Le Flèche P, Foster G, Tryland M, Ramisse F, Djønne B, Al Dahouk S, Jacques I, Neubauer H, Walravens K, Godfroid J, Cloeckaert A, Vergnaud G (July 2009). "MLVA-16 typing of 295 marine mammal Brucella isolates from different animal and geographic origins identifies 7 major groups within Brucella ceti and Brucella pinnipedialis". BMC Microbiology. 9 (1): 145. doi:10.1186/1471-2180-9-145. PMC 2719651. PMID 19619320.

- Van Bressem MF, Raga JA, Di Guardo G, Jepson PD, Duignan PJ, Siebert U, Barrett T, Santos MC, Moreno IB, Siciliano S, Aguilar A, Van Waerebeek K (September 2009). "Emerging infectious diseases in cetaceans worldwide and the possible role of environmental stressors". Diseases of Aquatic Organisms. 86 (2): 143–57. doi:10.3354/dao02101. PMID 19902843.

- Hernández-Mora G, Palacios-Alfaro JD, González-Barrientos R (April 2013). "Wildlife reservoirs of brucellosis: Brucella in aquatic environments". Revue Scientifique et Technique. 32 (1): 89–103. doi:10.20506/rst.32.1.2194. PMID 23837368. S2CID 9883215.

- Isidoro-Ayza M, Ruiz-Villalobos N, Pérez L, Guzmán-Verri C, Muñoz PM, Alegre F, Barberán M, Chacón-Díaz C, Chaves-Olarte E, González-Barrientos R, Moreno E, Blasco JM, Domingo M (September 2014). "Brucella ceti infection in dolphins from the Western Mediterranean sea". BMC Veterinary Research. 10: 206. doi:10.1186/s12917-014-0206-7. PMC 4180538. PMID 25224818.

Further reading

- Hernández-Mora G, Manire CA, González-Barrientos R, Barquero-Calvo E, Guzmán-Verri C, Staggs L, Thompson R, Chaves-Olarte E, Moreno E (June 2009). "Serological diagnosis of Brucella infections in odontocetes". Clinical and Vaccine Immunology. 16 (6): 906–15. doi:10.1128/CVI.00413-08. PMC 2691062. PMID 19386800.

- Davison NJ, Barnett JE, Perrett LL, Dawson CE, Perkins MW, Deaville RC, Jepson PD (July 2013). "Meningoencephalitis and arthritis associated with Brucella ceti in a short-beaked common dolphin (Delphinus delphis)". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 49 (3): 632–6. doi:10.7589/2012-06-165. PMID 23778612. S2CID 5221789.

- Davison NJ, Perrett LL, Law RJ, Dawson CE, Stubberfield EJ, Monies RJ, Deaville R, Jepson PD (July 2011). "Infection with Brucella ceti and high levels of polychlorinated biphenyls in bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) stranded in south-west England". The Veterinary Record. 169 (1): 14. doi:10.1136/vr.d2714. PMID 21676987. S2CID 207041816.

- González-Barrientos R, Morales JA, Hernández-Mora G, Barquero-Calvo E, Guzmán-Verri C, Chaves-Olarte E, Moreno E (May 2010). "Pathology of striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) infected with Brucella ceti". Journal of Comparative Pathology. 142 (4): 347–52. doi:10.1016/j.jcpa.2009.10.017. hdl:11056/18359. PMID 19954790.