Brussels City Museum

The Brussels City Museum (French: Musée de la ville de Bruxelles, Dutch: Museum van de Stad Brussel) is a municipal museum on the Grand-Place/Grote Markt of Brussels, Belgium. Conceived in 1860 and inaugurated in 1887, it is dedicated to the history and folklore of the City of Brussels from its foundation into modern times, which it presents through paintings, sculptures, tapestries, engravings, photos and models, including a notable scale-representation of the town during the Middle Ages.[1]

.jpg.webp) The Maison du Roi/Broodhuis building housing the Brussels City Museum | |

Interactive fullscreen map | |

| Established | 1887 |

|---|---|

| Location | Grand-Place/Grote Markt, B-1000 City of Brussels, Brussels-Capital Region, Belgium |

| Coordinates | 50°50′49″N 4°21′10″E |

| Type | History museum |

| Owner | City of Brussels |

| Website | Official website |

| Part of | La Grand-Place, Brussels |

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iv |

| Reference | 857 |

| Inscription | 1998 (22nd Session) |

The museum is situated on the north side of the square, opposite Brussels' Town Hall, in the Maison du Roi ("King's House") or Broodhuis ("Bread House" or "Bread Hall").[2][3][4] This building, erected between 1504 and 1536, was rebuilt in the 19th century in its current neo-Gothic style by the architect Victor Jamaer. Since 1998, is also listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, as part of the square.[5][6] It can be accessed from the premetro (underground tram) station Bourse/Beurs (on lines 3 and 4), as well as the bus stop Grand-Place/Grote Markt (on line 95).[7]

History

Medieval structures

Brussels' Town Hall was erected in stages, between 1401 and 1455, on the south side of the Grand-Place/Grote Markt, transforming the square into the seat of municipal power.[3] To counter this, from 1504 to 1536, the Duke of Brabant ordered the construction of a large Flamboyant edifice across from the city hall to house his administrative services.[8] It was erected on the site of the first cloth and bread markets, which were no longer in use.[9]

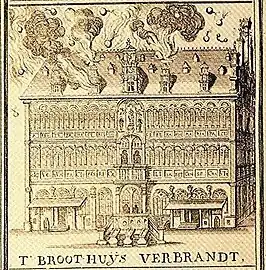

The building was first called the Duke's House (Middle Dutch: 's Hertogenhuys), but when Charles V, Duke of Brabant since 1506, was crowned King of Spain in 1516, it became known as the King's House (Middle Dutch: 's Conincxhuys). It is currently known as the Maison du Roi ("King's House") in French, although no king has ever lived there, though in Dutch it continues to be called the Broodhuis ("Bread House"), after the market whose place it took.[9] During Charles' reign, the building was completely redone by his court architect Antoon II Keldermans in a late Gothic style very similar to the contemporary design, although without towers or galleries. The projects were presented in 1514 and the construction took place between 1515 and 1536.[10]

In 1568, two statesmen, Lamoral, Count of Egmont and Philip de Montmorency, Count of Horn, who had spoken out against the policies of King Philip II in the Spanish Netherlands, were beheaded in front of the King's House.[11][12][13] This triggered the beginning of the armed revolt against Spanish rule, of which William of Orange took the lead.

![The King's House in Brussels, designed by Antoon II Keldermans [nl] in 1514](../I/Broodhuis_1640.jpg.webp) The King's House in Brussels, designed by Antoon II Keldermans in 1514

The King's House in Brussels, designed by Antoon II Keldermans in 1514

Carousel in front of the King's House in 1565 to mark the wedding of the Duke of Parma and Maria of Portugal

Carousel in front of the King's House in 1565 to mark the wedding of the Duke of Parma and Maria of Portugal

Destruction and rebuilding

The King's House suffered extensive damage in 1695 from the bombardment of Brussels by a French army under Marshal François de Neufville, duc de Villeroy.[8] The building was then roughly restored by the architect Jean Cosyn in 1697.[14] A second more thorough restoration followed in 1767 when it received a neoclassical portal and a large roof pierced with three oeil-de-boeuf windows. The statues of saints accompanying the Virgin Mary were replaced by those of an imperial eagle and a heraldic lion. This also led to the disappearance of the fountain from the portal.[2]

In the late 18th century, the building served as a Maison du Peuple/Volkshuis ("House of the People") during the occupation of Brussels by French Revolutionaries.[14] Having become national property, it was ceded to the City of Brussels, which sold it in 1811 to the Marquis Paul Arconati-Visconti. The latter did not keep it long; he resold it in 1817. The new owner rented it for the most diverse uses: from a court, to a temporary prison, a storage space for the British cavalry after the Battle of Waterloo, a rehearsal room of the School of Dance of the Theatre of La Monnaie, and a library.

In 1864, a new fountain made by the sculptor Charles-Auguste Fraikin was installed, topped with statues of the Counts of Egmont and Horn, on the site of their execution.[15]

The Grand-Place in flames during the bombardment of Brussels in 1695. The King's House is on the right.

The Grand-Place in flames during the bombardment of Brussels in 1695. The King's House is on the right. The King's House burning during the bombardment

The King's House burning during the bombardment%252C_Augustin_Coppens_-_Ruins_on_part_of_the_Grand_Place_from_the_corner_of_the_Heuvelstraat_to_St_Nicholas.jpg.webp) The surroundings of the King's House after the bombardment

The surroundings of the King's House after the bombardment The building following the neoclassical restoration

The building following the neoclassical restoration

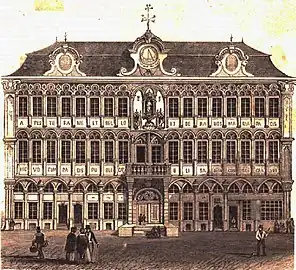

Neo-Gothic building

By the mid-19th century, the state of the building had deteriorated and a comprehensive renovation was sorely needed. Under the impulse of the city's then-mayor, Charles Buls, it was reconstructed once again between 1874 and 1896, in its current neo-Gothic form, by the architect Victor Jamaer, in the style of his mentor Eugène Viollet-le-Duc.[5] On that occasion, Jamaer built two galleries and a central tower. He also adorned the facade with statues and other decorations. At the rear, he added a new, much more sober wing in Flemish neo-Renaissance style. The new King's House was officially inaugurated in 1896.

During the works, the fountain-sculpture of the Counts of Egmont and Horn was moved to the Square du Petit Sablon/Kleine Zavelsquare, where it now has its back to the Egmont Palace.[15] Despite the fountain's move, the memory of the martyrs is still present at the site of their execution through commemorative plaques in French and Dutch, present since 1911 on either side of the entrance to the building, and replacing a previous plaque written only in French and sealed in the sidewalk.

The current building, whose interior was renovated in 1985, has housed the Brussels City Museum since 1887.[3][4] From 1928, the entire building was assigned to the museum's collections. After transformations, it reopened its doors in 1935 on the occasion of the Brussels International Exposition. On 9 March 1936, it was designated a historic monument, at the same time as the Town Hall.[16] It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1998 as part of the registration of the Grand-Place.[6]

The building before the neo-Gothic reconstruction campaign

The building before the neo-Gothic reconstruction campaign The building in the late 19th century, after reconstruction

The building in the late 19th century, after reconstruction_Brussels_City_Museum_Aug_2009_(crop).jpg.webp) The building as it appears today

The building as it appears today

Highlights

The Brussels City Museum features more than 7,000 items, including artefacts, paintings and tapestries from Brussels' history, such as the Town Hall's original sculptures.[2][17] There are two dioramas of the city of Brussels in its early days and as it began to flourish in the 1500s. The museum's painting collections include works by the Flemish Primitive Aert van den Bossche (15th century) and the French historical painter Charles Meynier (18th century).

The original statue of Manneken Pis is on view on the top floor. Many items of the statue's wardrobe, consisting of around one thousand different costumes, could also be viewed in a permanent exhibition inside the museum until February 2017, when a specially designed museum, called Garderobe MannekenPis, opened its doors nearby at 19, rue du Chêne/Eikstraat.[18]

The City Museum is open every day except Mondays from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. On the first Sunday of every month, admission to the museum is free.[4]

(2).jpg.webp) Martyrdom of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Aert van den Bossche, 1490

Martyrdom of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Aert van den Bossche, 1490.jpg.webp) Martyrdom of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Van den Bossche, 1490

Martyrdom of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Van den Bossche, 1490 The Grand-Place on fire during the night of 13th to 14th August 1695, Anonymous; 146 x 180 cm

The Grand-Place on fire during the night of 13th to 14th August 1695, Anonymous; 146 x 180 cm Heraldic lion, end of the 18th century

Heraldic lion, end of the 18th century Bonaparte first consul, Charles Meynier, 1804

Bonaparte first consul, Charles Meynier, 1804 The Botanical Garden, Paul Vitzthumb, 1828

The Botanical Garden, Paul Vitzthumb, 1828 Brussels' Town Hall and the Sunday market, Cornelis Christiaan Dommersen, 1887

Brussels' Town Hall and the Sunday market, Cornelis Christiaan Dommersen, 1887

See also

References

Notes

- Staff writer (2013). "Museum of the City of Brussels". Museums of the City. City of Brussels. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Hennaut 2000, p. 44–45.

- State 2004, p. 147.

- "Présentation - Brussels City Museum". www.brusselscitymuseum.brussels (in French). Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Staff writer (2011). "Museum of Brussels City (Musée de la Ville de Bruxelles)". Museums. Brussels.info. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- "La Grand-Place, Brussels". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "Ligne 95 vers GRAND-PLACE - STIB Mobile". m.stib.be. Retrieved 7 November 2021.

- "History of the Grand Place of Brussels". Commune Libre de l'Îlot Sacré. Retrieved 25 August 2009.

- Hennaut 2000, p. 19.

- Hennaut 2000, p. 17.

- Mardaga 1993, p. 122–123.

- De Vries 2003, p. 36.

- Heymans 2011, p. 16.

- Des Marez 1918, p. 34.

- Mardaga 1993, p. 123.

- "Bruxelles Pentagone - Maison du Roi - Grand-Place 29". www.irismonument.be. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- Fun, Everything is (10 March 2017). "Brussels City Museum". Brussels Museums. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- "New Brussels museum displays costumes of Manneken Pis statue". Reuters. 3 February 2017. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

Bibliography

- Culot, Maurice; Hennaut, Eric; Demanet, Marie; Mierop, Caroline (1992). Le bombardement de Bruxelles par Louis XIV et la reconstruction qui s'ensuivit, 1695–1700 (in French). Brussels: AAM éditions. ISBN 978-2-87143-079-7.

- De Vries, André (2003). Brussels: A Cultural and Literary History. Oxford: Signal Books. ISBN 978-1-902669-46-5.

- Des Marez, Guillaume (1918). Guide illustré de Bruxelles (in French). Vol. 1. Brussels: Touring Club Royal de Belgique.

- Hennaut, Eric (2000). La Grand-Place de Bruxelles. Bruxelles, ville d'Art et d'Histoire (in French). Vol. 3. Brussels: Éditions de la Région de Bruxelles-Capitale.

- Heymans, Vincent (2011). Les maisons de la Grand-Place de Bruxelles (in French). Brussels: CFC Éditions. ISBN 978-2-930018-89-8.

- State, Paul F. (2004). Historical dictionary of Brussels. Historical dictionaries of cities of the world. Vol. 14. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5075-0.

- Le Patrimoine monumental de la Belgique: Bruxelles (PDF) (in French). Vol. 1B: Pentagone E-M. Liège: Pierre Mardaga. 1993.