Bulldog

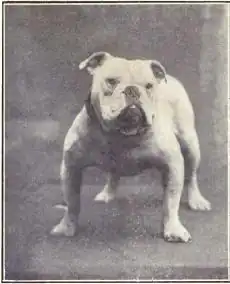

The Bulldog is a British breed of dog of mastiff type. It may also be known as the English Bulldog or British Bulldog. It is a medium-sized, muscular dog of around 40–55 lb (18–25 kg). They have large heads with thick folds of skin around the face and shoulders, and a relatively flat face with a protruding lower jaw. The breed has significant health issues as a consequence of breeding for its distinctive appearance, including brachycephalia, hip dysplasia, heat sensitivity, and skin infections. Due to concerns about their quality of life, breeding Bulldogs is illegal in Norway and the Netherlands.

| Bulldog | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other names | English Bulldog, British Bulldog | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Origin | England[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notes | National animal of United Kingdom | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Dog (domestic dog) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The modern Bulldog was bred as a companion dog from the Old English Bulldog, a now-extinct breed used for bull-baiting, when the sport was outlawed in England under the Cruelty to Animals Act. The Bulldog Club (In England) was formed in 1878, and the Bulldog Club of America was formed in 1890. While often used as a symbol of ferocity and courage, modern Bulldogs are generally friendly, amiable dogs. Bulldogs are now commonly kept as pets; in 2013 it was in twelfth place on a list of the breeds most frequently registered worldwide.[4]

History

The first reference to the word "Bulldog" is dated 1631 or 1632 in a letter by a man named Preswick Eaton where he writes: "procuer mee two good Bulldogs, and let them be sent by ye first shipp".[5] In 1666, English scientist Christopher Merret applied: "Canis pugnax, a Butchers Bull or Bear Dog", as an entry in his Pinax Rerum Naturalium Britannicarum.[6]

The designation "bull" was applied because of the dog's use in the sport of bull-baiting. This entailed the setting of dogs (after placing wagers on each dog) onto a tethered bull. The dog that grabbed the bull by the nose and pinned it to the ground would be the victor. It was common for a bull to maim or kill several dogs at such an event, either by goring, tossing, or trampling over them. Over the centuries, dogs used for bull-baiting developed the stocky bodies and massive heads and jaws that typify the breed, as well as a ferocious and savage temperament. Bull-baiting was made illegal in England by the Cruelty to Animals Act 1835.[7] Therefore, the Old English Bulldog had outlived its usefulness in England as a sporting animal and its "working" days were numbered. However, emigrants did have a use for such dogs in the New World. In mid-17th century New York, Bulldogs were used as a part of a citywide roundup effort led by Governor Richard Nicolls. Because cornering and leading wild bulls was dangerous, Bulldogs were trained to seize a bull by its nose long enough for a rope to be secured around its neck.[8]

Bulldogs as pets were continually promoted by dog dealer Bill George.[9]

In 1864, a group of Bulldog breeders under R. S. Rockstro founded the first Bulldog Club. Three years after its opening the Club ceased to exist, not having organized a single show. The main achievement of the Rockstro Bulldog Club was a detailed description of the Bulldog, known as the Philo-Kuan Standard. Samuel Wickens, treasurer of the club, published this description in 1865 under the pseudonym Philo-Kuan.[10]

On 4 April 1873, The Kennel Club was founded, the first dog breeding club dealing with the registration of purebred dogs and dog breeds.[11] Bulldogs were included in the first volume of the Kennel Club Stud Book, which was presented at the Birmingham Show on 1 December 1874. The first English Bulldog entered into the register was a male dog named Adam (Adamo), born in 1864.[12]

In March 1875, the third Bulldog Club was founded, which still exists today.[13][14] Members of this club met frequently at the Blue Post pub on Oxford Street in London. The founders of the club collected all available information about the breed and its best representatives and developed a new standard for the English Bulldog, which was published on 27 May 1875, the same year they held the first breed show. Since 1878, exhibitions of the club were held annually, except during the Second World War. On 17 May 1894, the Bulldog Club was granted the status of a corporation and since then has carried the official name "The Bulldog Club, Inc.". It is the oldest mono-breed dog kennel club in the world.[15]

The Bulldog was officially recognized by the American Kennel Club in 1886.[16]

In 1894 the two top Bulldogs, King Orry and Dock Leaf, competed in a contest to see which dog could walk 20 miles (32 km). King Orry was reminiscent of the original Bulldogs, lighter boned and very athletic. Dock Leaf was smaller and heavier set, more like modern Bulldogs. King Orry was declared the winner that year, finishing the 20-mile (32 km) walk while Dock Leaf collapsed and expired.[17] Though today Bulldogs look tough, they cannot perform the job they were originally bred for, as they cannot withstand the rigors of running after and being thrown by a bull, and also cannot grip with such a short muzzle. Although not as physically capable as their ancestors, modern Bulldogs are much calmer and less aggressive.[18]

Description

Appearance

Bulldogs have characteristically wide heads and shoulders along with a pronounced mandibular prognathism. There are generally thick folds of skin on the brow; round, black, wide-set eyes; a short muzzle with characteristic folds called a rope or nose roll above the nose; hanging skin under the neck; drooping lips and pointed teeth, and an underbite with an upturned jaw. The coat is short, flat, and sleek with colours of red, fawn, white, brindle, and piebald.[16] They have short tails that can either hang down straight or be tucked in a coiled "corkscrew" into a tail pocket.

In the United Kingdom, the breed standards are 55 lb (25 kg) for a male and 50 lb (23 kg) for a female.[19] In the United States, the standard calls for a smaller dog — a typical mature male weighs 50 lb (23 kg), while mature females weigh about 40 lb (18 kg).[20]

Temperament

According to the American Kennel Club (AKC), a Bulldog's disposition should be "equable and kind, resolute, and courageous (not vicious or aggressive), and demeanor should be pacifist and dignified. These attributes should be countenanced by the expression and behavior".[21]

Breeders have worked to remove aggression from the breed.[16] Most have a friendly, patient, but stubborn nature. Bulldogs are recognized as excellent family pets because of their tendency to form strong bonds with children.[16] Generally, Bulldogs are known for getting along well with children, other dogs, and other pets.[22][23]

Health

Lifespan

Despite slow maturation so that growing up is rarely achieved by two and a half years, Bulldogs' lives are relatively short. At five to six years old, they start to show signs of aging. A 2004 UK survey of 180 Bulldog deaths puts the median age at death at 6 years 3 months. The leading cause of death of Bulldogs in the survey was cardiac related (20%), cancer (18%), and old age (9%). Those that died of old age had an average lifespan of 10 to 11 years.[2] A 2013 UK vet clinic survey of 26 Bulldogs puts the median lifespan at 8.4 years with an interquartile range of 3.2–11.3 years.[3] The UK Bulldog Breed Council website lists the average life span of the breed as 8–10 years.[24]

Breed-linked disorders

A study by the Royal Veterinary College found that Bulldogs are a much less healthy breed than average, with over twice the odds of being diagnosed with at least one of the common dog disorders investigated in the study.[25]

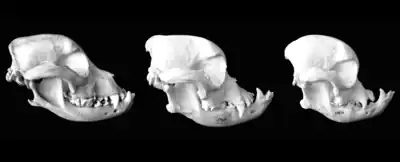

The English Bulldog is among the breeds that are most severely affected by brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome, due to extreme brachycephalia (shortened snout), a large tongue and palate, and other morphological issues.[26][27] Like all brachycephalic dogs, bully breeds often suffer from brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome (BAOS). A degree of BOAS has been normalized in the breed, as an inevitable consequence of their distinctive face.[26] The condition manifests in a variety of ways, often in the form of intolerance to heat and physical exertion. Since dogs regulate heat primarily by panting, Bulldogs are very sensitive to heat; they may actually gain rather than lose heat due to their inefficient breathing, leading to a vicious cycle. Bulldogs must be given plenty of shade and water, and must be kept out of standing heat.[16][28] They can even die from hyperthermia.[16] Bulldogs can be heavy breathers and tend to be loud snorers with interrupted sleep; another indicator of brachycephalic airway obstructive syndrome.[29] Many airlines ban the breed from flying in the cargo hold due to a high rate of deaths from air pressure interacting poorly with their breathing problems.[30]

Statistics from the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals indicate that of the 467 Bulldogs tested between 1979 and 2009 (30 years), 73.9% were affected by hip dysplasia, the highest amongst all breeds.[31] Similarly, the breed has the worst score in the British Veterinary Association/Kennel Club Hip Dysplasia scoring scheme, although only 22 Bulldogs were tested in the scheme.[32] Patellar luxation affects 2.9% of Bulldogs.[33]

Like all dogs, Bulldogs require daily exercise, which is often made difficult due to their breathing problems, hip dysplasia, and other health issues. If not properly exercised it is possible for a Bulldog to become overweight, which could lead to heart and lung problems, as well as stress on the joints.[34]

Some individuals of this breed are prone to interdigital cysts—cysts that form between the toes. These cause the dog some discomfort, but are treatable either by vet or an experienced owner. Other problems can include cherry eye, a protrusion of the inner eyelid (which can be corrected by a veterinarian), allergies, and hip issues in older Bulldogs. The folds, or "rope", on a Bulldog's face should be cleaned daily to avoid infections caused by moisture accumulation.[35] Some Bulldogs' naturally curling tails can be so tight to the body as to require regular cleaning and ointment. Due to the high volume of skin folds on the Bulldog's body, they have high prevalence of skin-fold dermatitis.[36]

Over 80% of Bulldog litters are delivered by Caesarean section because their characteristically large heads can become lodged in the mother's birth canal and to avoid potential breathing problems for the mother during labor.[37][38]

Controversies and legal status

In January 2009, after the BBC documentary Pedigree Dogs Exposed, The Kennel Club introduced revised breed standards for the British Bulldog, along with 209 other breeds, to address health concerns. Opposed by the British Bulldog Breed Council, it was speculated by the press that the changes would lead to a smaller head, fewer skin folds, a longer muzzle, and a taller thinner posture, in order to combat problems with respiration and breeding due to head size and width of shoulders.[39] In 2019 the Dutch Kennel Club implemented some breeding rules to improve the health of the Bulldog. Among these is a fitness test where the dog has to walk 1 km (0.62 miles) in 12 minutes. Its temperature and heart rate has to recover after 15 minutes.[40]

In 2014, the Dutch government forbade breeding of dogs with a snout shorter than a third of the skull, including Bulldogs, a law which it began enforcing in 2019.[41] In 2022, the Oslo District Court made a ruling that banned the breeding of Bulldogs in Norway due to their propensity for developing health problems. In its verdict the court judged that no dog of this breed could be considered healthy, therefore using them for breeding would be a violation of Norway’s Animal Welfare Act.[42][43]

Cultural significance

Bulldogs are often associated with determination, strength, and courage due to their historical occupation, though the modern-day dog is bred for appearance and friendliness and not suited for significant physical exertion. They are often used as mascots by universities, sports team, and other organizations. Some of the better known Bulldog mascots include Butler's Blue IV, Yale's Handsome Dan, the University of Georgia's Uga, Mississippi State's Bully, and United States Marine Corps' Chesty.[34][44]

The Bulldog originated in England and has a longstanding association with British culture; the BBC wrote: "to many the Bulldog is a national icon, symbolising pluck and determination".[45] During the Second World War, the Prime Minister Winston Churchill was likened to a Bulldog for his defiance of Nazi Germany.[46]

References

- Wilcox, Charlotte (1999). The Bulldog. Capstone Press. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7368-0004-4.

- "2004 Purebred Dog Health Survey" (PDF). Kennel Club/British Small Animal Veterinary Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 February 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- O’Neill, D. G.; Church, D. B.; McGreevy, P. D.; Thomson, P. C.; Brodbelt, D. C. (2013). "Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England" (PDF). The Veterinary Journal. 198 (3): 638–43. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020. PMID 24206631. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 May 2018. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- [Svenska Kennelklubben] (2013). Registration figures worldwide – from top thirty to endangered breeds Archived 23 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine. FCI Newsletter 15. Fédération Cynologique Internationale. Accessed March 2022.

- Jesse, George R. (1866). Researches into the history of the British Dog, from ancient laws, charters, and historical records: With original anecdotes, and illustrations of the nature and attributes of the dog, from the poets and prose writers of ancient, mediaeval, and modern times. With engravings designed and etched by the author. Rob. Hardwicke. p. 306. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 17 November 2015.

- Merret, Christopher (1666). Pinax Rerum Naturalium Britannicarum, continens Vegetabilia, Animalia, et Fossilia. p. 169. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- Curnutt, Jordan (2001). Animals and the Law: A Sourcebook. ABC-CLIO. p. 284. ISBN 9781576071472. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 13 September 2020.

- Ellis, Edward Robb (2005). The Epic of New York City – A Narrative History. Basic Books, New York. ISBN 978-0-7867-1436-0

- Oliff, D. B. (1988) The Mastiff and Bullmastiff Handbook, The Boswell Press ISBN 0-85115-485-9.

- "The Origin of the English Bulldog Standard". Bulldog Information. Archived from the original on 12 March 2004. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "History of the Kennel Club". The Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 18 September 2020. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "The History of the English Bulldog". Ready Set Puppy. Archived from the original on 6 March 2021. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "History of the English Bulldog". Bulldog Information. Archived from the original on 29 October 2005. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "Origins of the English Bulldog". Bulldog Club do Brasil. Archived from the original on 12 January 2002. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "The first Bulldog breed Clubs and first Bulldog Champions". Bulldog Information. Archived from the original on 4 January 2006. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- "Get to Know the Bulldog" Archived 22 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine, 'The American Kennel Club'. Retrieved 29 May 2014

- The sun., 11 September 1894, Page 4, Image 4 Archived 4 September 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- Thomson, K.S. (1996). "The Fall and Rise of the English Bulldog". American Scientist. 84 (3): 220. Bibcode:1996AmSci..84..220T. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- "Bulldog breed standard". The Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 23 August 2020. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- "Home of the Official AKC Bulldog Breed Club". The Bulldog Club of America. Archived from the original on 25 September 2021. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- American Kennel Club – Bulldog Archived 13 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Akc.org. Retrieved 9 June 2012.

- Ewing, Susan (2006). Bulldogs for dummies. Indiana: Wiley Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7645-9979-8. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 9 November 2020.

- "Bulldog - Did You Know?". Animal On Planet. 12 May 2021. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- Frequently asked questions on The Bulldog, 'Britain's National Breed' Archived 18 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine Bulldog Breed Council

- O'Neill, Dan G.; Skipper, Alison; Packer, Rowena M. A.; Lacey, Caitriona; Brodbelt, Dave C.; Church, David B.; Pegram, Camilla (15 June 2022). "English Bulldogs in the UK: a VetCompass study of their disorder predispositions and protections". Canine Medicine and Genetics. 9 (1): 5. doi:10.1186/s40575-022-00118-5. ISSN 2662-9380. PMC 9199211. PMID 35701824.

- "Brachycephalic Airway Obstruction Syndrome and the English Bulldog". Universities Federation for Animal Welfare. The International Animal Welfare Science Society. 2011. Archived from the original on 13 February 2020. Retrieved 13 February 2020.

- Pedersen, Niels C.; Pooch, Ashley S.; Liu, Hongwei (29 July 2016). "A genetic assessment of the English bulldog". Canine Genetics and Epidemiology. 3 (1): 6. doi:10.1186/s40575-016-0036-y. ISSN 2052-6687. PMC 4965900. PMID 27478618. Archived from the original on 21 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- "Heatstroke warning for bulldogs and pugs". BBC News. 18 June 2020. Archived from the original on 22 February 2022. Retrieved 22 February 2022.

It's likely that brachycephalic [flat-faced] dogs overheat due to their intrinsically ineffective cooling mechanisms. Dogs pant to cool down - without a nose, panting is simply less effective. In fact, brachycephalic dogs may even generate more heat simply gasping to breathe than they lose by panting.

- "English Bulldog - Brachycephalic Airway Obstruction Syndrome (BAOS)". www.ufaw.org.uk. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- Haughney, Christine (7 October 2011). "Banned by Many Airlines, These Bulldogs Fly Private". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 7 October 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- "Hip Dysplasia Statistics: Hip Dysplasia by Breed". Orthopedic Foundation for Animals. Archived from the original on 19 October 2010. Retrieved 10 February 2010.

- "British Veterinary Association/Kennel Club Hip Dysplasia Scheme – Breed Mean Scores at 01/11/2009" (PDF). British Veterinary Association. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 27 February 2010.

- Patellar Luxation Statistics Archived 25 December 2022 at the Wayback Machine. blueeyesbulldogs.com

- Denizet-Lewis, Benoit (22 November 2011) Can the Bulldog be Saved? Archived 13 March 2021 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times.

- Paretts, Susan (20 August 2020). "Bulldog Puppy Training Timeline: What to Expect and When to Expect It". American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 19 January 2023. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- Asher, Lucy; Diesel, Gillian; Summers, Jennifer F.; McGreevy, Paul D.; Collins, Lisa M. (December 2009). "Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 1: Disorders related to breed standards". The Veterinary Journal. 182 (3): 402–411. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.08.033. PMID 19836981.

- "English Bulldog - Dystocia". www.ufaw.org.uk. Retrieved 30 January 2023.

- Evans, K.; Adams, V. (2010). "Proportion of litters of purebred dogs born by caesarean section" (PDF). The Journal of Small Animal Practice. 51 (2): 113–118. doi:10.1111/j.1748-5827.2009.00902.x. PMID 20136998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 April 2016.

- Elliott, Valerie (14 January 2009). "Healthier new Bulldog will lose its Churchillian jowl". The Times. London. Archived from the original on 16 January 2009. Retrieved 14 January 2009.

- "Convenant Bulldog, breeding rules" (PDF). Raad van Beheer (Dutch Kennel Club). Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- "Dutch to crack down on breeding of dogs with too short snouts | Vet Times". vettimes.co.uk. 31 May 2019. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- "Norway bans breeding of British Bulldogs and Cavalier King Charles spaniels". The Independent. 2 February 2022. Archived from the original on 10 February 2022. Retrieved 11 February 2022.

- "Breeding ban for bulldogs and cavaliers in Norway". France 24. 22 February 2022. Archived from the original on 28 March 2022. Retrieved 28 March 2022.

- Burke, Anna (25 May 2018). "The Legacy of Chesty: How a Bulldog Became the United States Marine Corps Mascot". American Kennel Club. Archived from the original on 18 January 2023. Retrieved 18 January 2023.

- "English Bulldog health problems prompt cross-breeding call". BBC. 12 December 2016. Archived from the original on 8 November 2020. Retrieved 21 June 2018.

- Baker, Steve (2001). Picturing the Beast. University of Illinois Press. p. 52. ISBN 0-252-07030-5.