Ox-wagon

An ox-wagon or bullock wagon is a four-wheeled vehicle pulled by oxen (draught cattle). It was a traditional form of transport, especially in Southern Africa but also in New Zealand and Australia. Ox-wagons were also used in the United States. The first recorded use of an ox-wagon was around 1670, but they continue to be used in some areas up to modern times.

Design

Ox-wagons are typically drawn by teams of oxen, harnessed in pairs. This gave them a very wide turning circle, the legacy of which are the broad, pleasant boulevards of cities such as Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, which are 120 feet (37 m) wide,[1] and Grahamstown, South Africa, which are "wide enough to turn an ox-wagon".

The wagon itself is made of various kinds of wood, with the rims of the wheels being covered with tyres of iron, and since the middle of the 19th century the axles have also been made of iron. The back wheels are usually substantially larger than the front ones and rigidly connected to the tray of the vehicle. The front wheels are usually greater in diameter than the clearance under the tray of the vehicle so that the steering axle could not turn far under the tray. This makes little difference to the turning circle of the wagon because of the oxen drawing it (see above) and it makes the front of the wagon much more stable because the track is never much less than the width of the tray. It also allowed a much more robust connection between the hauling traces of the oxen and the rear axle of the wagon (usually iron chain or rods) that is necessary for heavy haulage.

Most of the load-carrying area was covered in canvas supported by wooden arches; the driver sat in the open on a wooden chest (Afrikaans: wakis).

- Examples of ox-wagons

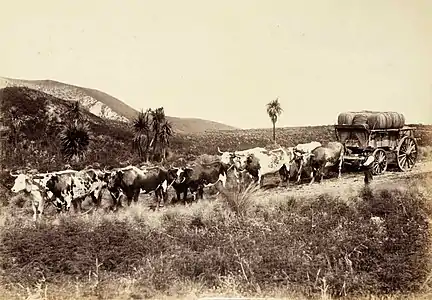

Bullock wagon carrying wool in New Zealand, c1880.

Bullock wagon carrying wool in New Zealand, c1880. Bullock Team drawing II Ton Marshall Engine (Australia early 20th century)

Bullock Team drawing II Ton Marshall Engine (Australia early 20th century) Ox-wagon with four wagon wheels.

Ox-wagon with four wagon wheels. Ox-wagon front axle assembly.

Ox-wagon front axle assembly.

Australia

Bullock wagons were important in the colonial history of Australia.[2] Olaf Ruhen, in his book Bullock Teams remarks on how bullock teams "shaped and built the colony. They carved the roads and built the rail; their tractive power made populating the interior possible; their contributions to the harvesting of timber opened the bush; they offered a start in life to the enterprising youngster". Bullocks were preferred by many explorers and teamsters because they were cheaper, quieter, tougher and more easily maintained than horses therefore making them more popular for draught work.[3] Frequently comprising long trains of bullocks, yoked in pairs, they were used for hauling drays, wagon or jinker loads of goods and lumber prior to the construction of railways and the formation of roads. In early days the flexible two-wheeled dray, with a centre pole and narrow 3-inch (8 cm) iron tyres was commonly used. The four-wheeled dray or box wagon came into use after about 1860 for loads of 6 to 8 long tons (6.7 to 9.0 short tons; 6.1 to 8.1 t) and was drawn by 16 to 18 bullocks. A bullock team was led by a pair of well trained leaders who responded to verbal commands as they did not have reins or a bridle.[4] The bullock team driver was called a bullocky, bullock puncher or teamster.

Many Australian country towns owe their origin to the bullock teams, having grown from a store or shanty where teams rested or crossed a stream. These shanties were spaced at about 12-mile (19 km) intervals, which was the usual distance for a team to travel in a day.[5]

South Africa

The Voortrekkers used ox-wagons (Afrikaans: Ossewa) during the Great Trek north and north-east from the Cape Colony in the 1830s and 1840s. An ox-wagon traditionally made with the sides rising toward the rear of the wagon to resemble the lower jaw-bone of an animal is also known as a kakebeenwa (jaw-bone wagon). South Africa has 800 varieties of wood of which 17 varieties were used for wagon building. South African wood varieties are regarded as the best for wagon building. Wood varieties used for wagon making ranged from hard yellowwood to Boekenhout, is a softer wood and was used as a shock absorber but still stayed firmly in place. The iron rim around the wheel was burnt onto the wheel, the charcoal would protect the iron rim from rust and rot, making it easy to cross rivers. The ox-wagon could be pulled by 12-16 oxen.[6]

The ox-wagon could also be disassembled in five minutes by hitting out four pegs on the wheels, then lifting the top of the wagon in seven pieces and carried by four people over rough terrain or across rivers. The ox-wagon could also twist 40 degrees which made it ideal for traversing difficult surface areas. The wheels of the ox-wagon were painted in red lead paint which acted as an excellent water repellant. Various flower and ornament designs were also painted on the wagons and the chests the wagons carried, making them look very colourful.[7]

Often the wagons where employed as a mobile fortification called a laager, such as was the case at the Battle of Blood River.

After the discovery of gold in the Barberton area in 1881, ox-wagons were used to bring in supplies from former Lourenço Marques. James Percy FitzPatrick worked on those ox-wagons and described them in his famous 1907 book Jock of the Bushveld.

Afrikaner symbolism

In South Africa, the ox-wagon was adopted as an Afrikaner cultural icon. The ossewa is mentioned in the first verse of "Die Stem", the Afrikaans poem which became South Africa's national anthem from 1957 to 1994. When a pro-German Afrikaner nationalist organisation formed in 1939, to oppose South Africa's entry into World War II on the British side, it called itself the Ossewabrandwag (Ox-wagon Sentinel).[8]

Gallery

- South African cultural heritage

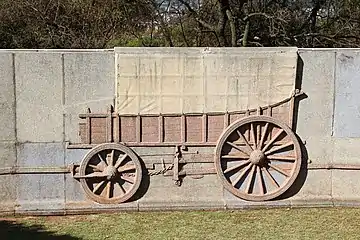

Relief of an ox-wagon on the laager wall

Relief of an ox-wagon on the laager wall A replica kakebeenwa located in the Kruger Museum

A replica kakebeenwa located in the Kruger Museum The Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria is encircled by a wall depicting Ox-wagons

The Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria is encircled by a wall depicting Ox-wagons

See also

- Bullock cart (ox-cart)

- Bullocky

- Carriage

- Chuckwagon

- Conestoga wagon

- Oxbow

- Wagon

References

- Pakenham, Thomas (1992) [1991]. "Chap. 27 Rhodes, Raiders and Rebels". The Scramble for Africa. London: Abacus. pp. 496–497. ISBN 0-349-10449-2.

- The Australian Encyclopaedia. The Grolier Society. Halstead Press, Sydney.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - "Annual Berry Show". webcache.googleusercontent.com. Archived from the original on 9 December 2012. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Beattie, William A. (1990). Beef Cattle Breeding & Management. Popular Books, Frenchs Forest. ISBN 0-7301-0040-5.

- "Chisholm, Alec H.". The Australian Encyclopaedia. Vol. 2. Sydney: Halstead Press. 1963. p. 181. Bullock-driving.

- Davie, Lucille. "Step into a wagon and go back 200 years". The Heritage Portal. Retrieved 9 October 2018.

- Davie, Lucille. "Step into a wagon and go back 200 years". The Heritage Portal.

- Williams, Basil (1946). Botha Smuts And South Africa. London: Hodder And Stoughton. pp. 160–161.