Burchardi flood

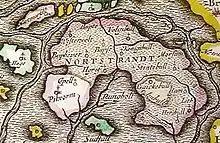

The Burchardi flood (also known as the second Grote Mandrenke) was a storm tide that struck the North Sea coast of North Frisia, Dithmarschen (in modern-day Germany) and southwest Jutland (in modern-day Denmark) on the night between 11 and 12 October 1634. Overrunning dikes, it shattered the coastline and caused thousands of deaths (8,000 to 15,000 people drowned) and catastrophic material damage. Much of the island of Strand washed away, forming the islands Nordstrand, Pellworm and several halligen.

.jpg.webp) Contemporary picture of the flood | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Duration | 11–12 October 1634 |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 8,000–15,000 |

| Areas affected | North Frisia, Dithmarschen, Hamburg area, southwest Jutland |

Background

The Burchardi flood hit Schleswig-Holstein during a period of economic weakness. In 1603 a plague epidemic spread across the land, killing many. The flooding occurred during the Thirty Years' War, which also did not spare Schleswig-Holstein. Fighting had occurred between locals and the troops of Frederick III, Duke of Holstein-Gottorp, especially on Strand Island. The people of Strand were resisting changes to their old defence treaties and the forced accommodation of troops. Supported by a Danish expeditionary fleet, they succeeded in repulsing first an imperial army and later the duke's men, but were eventually defeated in 1629. The island and subsequently also the means of coastal protection suffered from the strife.

The Burchardi flood was merely the last in a series of floods that hit the coastline of Schleswig-Holstein in that period. In 1625, great ice-floats had already caused major damage to the dikes.[1] Several storm floods are reported by the chronicles during the years prior to 1634; the fact that the dikes did not hold even during summer provides evidence for their insufficient maintenance.

Course of events

While the weather had been calm for weeks prior to the flood, a strong storm occurred from the east on the evening of 11 October 1634[2] which turned southwest during the evening and developed into a European windstorm from the northwest. The most comprehensive report is preserved from Dutch hydraulic engineer Jan Leeghwater who was tasked with land reclamation in a part of the Dagebüll bay. He writes:[3]

In the evening a great storm and bad weather rose from the southwest out of the sea. ... The wind began to blow so hard that no sleep could touch our eyes. When we had been lying in bed for about an hour my son said to me, 'Father, I feel water dripping into my face'. The waves were rising up at the sea dike and onto the roof of the house. It was a very frightening sound.

Leeghwater and his son fled over the dike towards a manor which was situated on higher terrain while the water had almost reached the top of the dike. At the time there were 38 persons in that manor, 20 of whom were refugees from lower lands. He continues:[4]

The wind turned somewhat to the northwest and blew plainly against the manor, so hard and stiff as I had never experienced in my life. On a strong door on the western side of the building the lock bars sprang out of the posts due to the sea waves, so that the water doused the [hearth] fire and ran into the corridors and over my knee boots, about 13 feet higher than the May floods of the old land. ... At the northern edge of the house which stood close to the tidal channel, the earth was washed away from underneath the house. ... Therefore the house, the hallway and the floor burst into pieces. ... It seemed that the manor and all those inside were doomed to be washed off the dike. In the morning, ... the tents and huts that had been standing all across the estate were washed away, thirty-six or thirty-seven in number, with all the people who had been inside. Great sea ships were standing high upon the dike as I have seen myself. In Husum, several ships were standing upon the highway. I have also ridden there along the beach and have seen wondrous things, many different dead beasts, beams of houses, smashed wagons and an awful lot of wood, straw and stubbles. And I have also seen many a human body who had drowned.

The witness Peter Sax from Koldenbüttel described the scenario as follows:[5]

...at six o'clock at night the Lord God began to fulminate with wind and rain from the east; at seven He turned the wind to the southwest and let it blow so strong that hardly any man could walk or stand; at eight and nine all dikes were already smitten... The Lord God [sent] thunder, rain, hail lightning and such a powerful wind that the Earth's foundation was shaken... at ten o'clock everything was over.

In combination with half a spring tide, the wind was pushing the water against the coastline with such a force that the first dike broke in the Stintebüll parish on Strand island at 10 p.m. About two hours past midnight the water had reached its peak level. Contemporary reports write of a water level on the mainland of ca. 4 metres (13 ft) above mean high tide, which is only slightly below the all-time highest flood level that was recorded at Husum during the 1976 flood with 4.11 metres (13 ft) above mean high tide.

The water rose so high that not only were the dikes destroyed but also houses in the shallow marshlands and even those on artificial dwelling hills were flooded. Some houses collapsed while others were set on fire due to unattended fireplaces.

Direct consequences

In this night the dikes broke at several hundred locations along the North Sea coastline of Schleswig-Holstein and southwestern Jutland. Estimations of fatalities range from 8,000 to 15,000. 8,000 local victims are counted by contemporary sources and from comparisons of parish registers. The actual number is might be much higher, though, because according to Anton Heimreich's Nordfriesische Chronik "many alien threshers and working people had been in the land whose number could just not be accounted for with certainty."[6]

On Strand alone at least 6,123 people (or 2/3 of the entire population of the island) and 50,000 livestock lost their lives due to 44 dike breaches. The water destroyed 1,300 houses and 30 mills. All 21 churches on Strand were heavily damaged, 17 of which were completely destroyed. Almost the entire new harvest was lost. And the island of Strand was torn apart, forming the smaller islands Nordstrand and Pellworm and the halligen Südfall and Nordstrandischmoor. The Nübbel and Nieland halligen were submerged in the sea.

On the Eiderstedt peninsula, 2,107 people and 12,802 livestock drowned and 664 houses were destroyed by the flood according to Heimreich's chronicle. Heimreich counts 383 dead in Dithmarschen. 168 people died, 1,360 livestock were lost, and 102 houses "drifted away" died in Busen parish (today's Büsum) and the areas along the mouth of the river Eider. Numerous people were killed in the coastal marshlands and victims were recorded even in settlements in the back-country like Bargum, Breklum, Almdorf or Bohmstedt. Even in Hamburg dikes broke in the Hammerbrook and Wilhelmsburg quarters. In Lower-Saxony, the dike of Hove broke at a length of 900 m.

The ambitious project by the Dukes of Gottorp to shut off the bay of Dagebüll, today's Bökingharde, with one single, large dike, which had been progressing after ten years of hard work, was now finally destroyed by the flood. Fagebüll and Fahretoft (which were still halligen back then) suffered great losses of land and lives. The church of Ockholm was destroyed and the sea dike had to be relocated landwards.

In southwestern Jutland, the Danish town of Ribe (a historically very important location and the main and largest town in that region) was entirely flooded and all dikes were penetrated. The Ribe Cathedral, which is located at a high point in the town that is c. 4 m (13 ft) above normal sea level, was flooded by 1.6–1.8 m (5–6 ft) of water.[7] Although southwestern Jutland has experienced several severe floods, this is the highest ever recorded (also exceeding the historical Saint Marcellus's flood and the modern Cyclone Anatol flood) and today it is marked as the top point on a flood pillar in Ribe. Markings after the flood can also still be seen on the cathedral's walls.[8][9] Limited data is available on the number of fatalities, but in Nørre Farup parish (just north of Ribe) about half the population drowned and there were records of people drowning as far as inland as Seem, normally located 14 km (8.7 mi) from the sea.[7]

Long-term effects

The Burchardi flood had especially severe consequences for Strand island where large parts of the land were lying below sea level. For weeks and months after the flood the water did not run off. Due to tidal currents the size of the dike breaches increased and several dike lines were eventually completely washed into the sea. This meant that a lot of arable land which had still been worked on directly after the flood had to be abandoned in later times because it could not be kept against the intruding sea. Saline sea water frequently submerged the fields of Strand so that they could no longer be used for agriculture.

M. Löbedanz, the preacher of Gaikebüll, describes the situation on Nordstrand after the flood:[10]

More than half of the dwelling places have been wasted and the houses have been washed away. Wasted are the other houses and windows, doors and walls are broken: wasted are entire parishes and in many of those only few houseowners are left: wasted are the Lord's houses, and neither preachers nor houseowners are left in numbers to frequent them.

In cultural terms, the Old Nordstrand variety of the North Frisian language was lost. The number of victims who spoke the idiom was too high and moreover many islanders moved their homes to the mainland or the higher hallig Nordstrandischmoor – against the order of Duke Frederick III.

By 1637 dikes on Pellworm were restored for 1,800 hectares of land. On Nordstrand however, the remaining farmers lived on dwelling hills like the hallig people and were hardly able to cultivate their fields. Despite several orders by the Duke, they failed in restoring the dikes. According to the Nordstrand dike law, those who could not secure land against the sea with dikes forfeit it. Finally the Duke enforced the Frisian law of De nich will dieken, de mutt wieken (Low German:"Who does not want to build a dike, shall lose ground"), expropriated the locals and attracted foreign settlers with a charter that promised land and considerable privileges to investors in dikes, like the sovereignty of policing and justice. One such investor was the Dutch entrepreneur Quirinus Indervelden who managed to create the first new polder in 1654 with Dutch money and expert workers from Brabant. Other polders followed in 1657 and 1663. This Dutch settlement is still present today in form of an Old Catholic churchhouse. The Old Catholic Dutchmen had been allowed to practise their religion in Lutheran Denmark and to erect their own church. Until 1870 the preacher there used to hold the sermon in Dutch.

In the course of further land reclamation, both islands Pellworm and Nordstrand today have a total area of ca. 9,000 hectares which is one third of old Strand island. Between the islands, the Norderhever tidal channel was formed which has gained up to 30 m of depth during the last 370 years. It has frequently been a threat to the geological foundations of Pellworm.[11]

Contemporary reaction

The people of the time could only imagine such a flood as a divine punishment from God. The evangelical enthusiast and poet Anna Ovena Hoyer interpreted the Burchardi Flood as the beginning of the apocalypse.[12]

References

- Citations

- Zitscher, Fritz-Ferdinand. "Der Einfluß der Sturmfluten auf die historische Entwicklung des nordfriesischen Lebensraumes", p. 169. In Reinhardt, Die erschreckliche Wasser-Fluth 1634

- Panten, Albert. "Der Chronist Hans Detleff aus Windbergen zur Flut von 1634", p. 8. In Reinhardt, Die erschreckliche Wasser-Fluth 1634, citing: Hans Detleff, Dithmarsische Historische Relation.

- cited after Riecken, p. 11 ff.: "gegen den Abend [hat] sich ein großer Sturm und Unwetter von Südwest her aus der See erhoben […] Da begann der Wind aus dem Westen so heftig zu wehen, daß kein Schlaf in unsere Augen kam. Als wir ungefähr eine Stunde auf dem Bett gelegen hatten, sagte mein Sohn zu mir „Vater, ich fühle das Wasser auf mein Angesicht tropfen“. Die Wogen sprangen am Seedeich in die Höhe auf das Dach des Hauses. Es war ganz gefährlich anzuhören."

- cited after Riecken, p. 11 ff.: "Der Wind drehte sich ein wenig nach Nordwesten und wehte platt gegen das Herrenhaus, so hart und steif, wie ich's in meinem Leben nicht gesehen habe. An einer starken Tür, die an der Westseite stand, sprangen die Riegel aus dem Pfosten von den Meereswogen, so daß das Wasser das Feuer auslöschte und so hoch auf den Flur kam, daß es über meine Kniestiefel hinweglief, ungefähr 13 Fuß höher als das Maifeld des alten Landes […] Am Nordende des Herrenhauses, welches dicht am Seetief stand, spülte die Erde unter dem Haus weg […] Infolgedessen barst das Haus, die Diele und der Boden auseinander […] Es schien nicht anders als solle das Herrenhaus mit allen, die darin waren, vom Deich abspülen. Des Morgens […] da waren alle Zelte und Hütten weggespült, die auf dem ganzen Werk waren, sechs- oder siebenunddreißig an der Zahl, mit allen Menschen, die darin waren. […] Große Seeschiffe waren auf dem hohen Deich stehengeblieben, wie ich selber gesehen habe. Mehrere Schiffe standen in Husum auf der hohen Straße. Ich bin auch den Strand allda geritten, da hab ich wunderliche Dinge gesehen, viele verschiedene tote Tiere, Balken von Häusern, zertrümmerte Wagen und eine ganze Menge Holz, Heu, Stroh und Stoppeln. Auch habe ich dabei so manche Menschen gesehen, die ertrunken waren."

- cited after Riecken, p. 35 ff.: ...um sechs Uhr am abend fing Gott der Herr aus dem Osten mit Wind und Regen zu wettern, um sieben wendete er den Wind nach dem Südwesten und ließ ihn so stark wehen, daß fast kein Menschen gehen oder stehen konnte, um acht und neun waren alle Deiche schon zerschlagen […] Gott der Herr ließ donnern, regnen, hageln, blitzen und den Wind so kräftig wehen, daß die Grundfeste der Erde sich bewegten […] um zehn Uhr war alles geschehen.

- cited after Riecken, p. 42: "viele fremde Drescher und Arbeitsleute im Lande gewesen, von deren Anzahl man so eben keine Gewissheit hat haben können."

- "Stormflod". Grænseforeningen. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- "De 5 største stormfloder i Vadehavet". Naturstyrelsen (Denmark's Ministry of Environment). 3 July 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- "Historiske stormfloder i Nordsøen og Danmark". Danish Meteorological Institute. 3 July 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2023.

- Kuschert, Rolf (1995). "Die frühe Neuzeit". In Nordfriisk Instituut (ed.). Geschichte Nordfrieslands (in German) (2nd ed.). Heide: Boyens & Co. ISBN 3-8042-0759-6.

Wüste liegen mehr denn die halben Wohnstädte, unnd sind die Häuser weggeschölet (weggespült); Wüste stehen die übrigen Häuser, unnd sind Fenstere, Thüren und Wende zerbrochen: Wüste stehen ganze Kirchspielen, unnd sind in etlichen wenig Haußwirthe mehr übrigen: Wüste stehen die Gotteshäuser, unnd sind weder Prediger noch Haußwirthe viel vorhanden, die diesselben Besuchen.

- Witez, Petra (2002). GIS-gestützte Analysen und dynamische 3D-Visualisierungen der morphologischen Entwicklung schleswig-holsteinischer Tidebecken (PDF) (in German). University of Kiel. p. 46. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2011-05-14.

- Hinrichs, Boy (1985). "Anna Ovena Hoyer und ihre beiden Sturmflutlieder". Nordfriesisches Jahrbuch (in German). 21: 195–221.

- Works cited

- Reinhardt, Andreas, ed. (1984). Die erschreckliche Wasser-Fluth 1634 (in German). Husum: Husum Druck- und Verlagsgesellschaft. ISBN 3-88042-257-5.

- Riecken, Guntram (1991). "Die Flutkatastrophe am 11. Oktober 1634 − Ursachen, Schäden und Auswirkungen auf die Küstengestalt Nordfrieslands". In Hinrichs, Boy; Panten, Albert; Riecken, Guntram (eds.). Flutkatastrophe 1634: Natur, Geschichte, Dichtung (in German) (2nd ed.). Neumünster: Wachholtz. pp. 11–64. ISBN 978-3-529-06185-1.

- General references

- Allemeyer, Marie Luisa (2009). "„In diesser erschrecklichen unerhörten Wasserfluth, kan man keine naturlichen Ursachen suchen". Die Burchardi-Flut des Jahres 1634 an der Nordseeküste". In Schenk, Gerrit Jasper (ed.). Katastrophen. Vom Untergang Pompejis bis zum Klimawandel (in German). Ostfildern: Thorbecke. pp. 93–108. ISBN 978-3-7995-0844-5.

- Hinrichs, Boy (1991). "Die Landverderbliche Sündenflut. Erlebnis und Darstellung einer Katastrophe". In Hinrichs, Boy; Panten, Albert; Riecken, Guntram (eds.). Flutkatastrophe 1634: Natur, Geschichte, Dichtung (in German) (2nd ed.). Neumünster: Wachholtz. ISBN 978-3-529-06185-1.

- Hinrichs, Boy; Panten, Albert; Riecken, Guntram, eds. (1991). Flutkatastrophe 1634: Natur, Geschichte, Dichtung (in German) (2nd ed.). Neumünster: Wachholtz. ISBN 978-3-529-06185-1.

- Jakubowski-Tiessen, Manfred (2003). "„Erschreckliche und unerhörte Wasserflut" Wahrnehmung und Deutung der Flutkatastrophe von 1634". In Jakubowski-Tiessen, Manfred; Lehmann, Hartmut (eds.). Um Himmels Willen. Religion in Katastrophenzeiten (in German). Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. pp. 179–200. ISBN 978-3-525-36271-6.

- Panten, Albert (1991). "Das Leben in Nordfriesland um 1600 am Beispiel Nordstrands". In Hinrichs, Boy; Panten, Albert; Riecken, Guntram (eds.). Flutkatastrophe 1634: Natur, Geschichte, Dichtung (in German) (2nd ed.). Neumünster: Wachholtz. pp. 65–80. ISBN 978-3-529-06185-1.

External links

- Changing coastline of Nordfriesland (Page in German). Shows maps of the coastline as changed during the last 1000 years

- Cor Snabel's "Flood of the Nordstrand Island, 1634" Archived 2011-07-24 at the Wayback Machine A rich resource including the eyewitness account of the hydraulic engineer Jan Leeghwater.