Burning of Wildgoose Lodge

53.9268793°N 6.6239075°W[nb 1]

The Burning of Wildgoose Lodge was an arson and murder attack on Wildgoose Lodge, County Louth, Ireland, on the night of 29–30 October 1816, in which eight occupants were killed, including an infant aged five months.[4] The house was near the County Monaghan border,[5] in the townland of Reaghstown, civil parish of Philipstown, barony of Ardee.[1][6] Eighteen men were executed for the crime, many of them innocent. The event inspired an 1830 short story by William Carleton (1794–1869) and the circumstances have been the subject of historical and political debate.

William Carleton's account

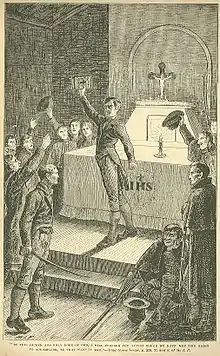

In 1817, William Carleton went to Killanny, Co. Louth, and for six months acted as tutor in the family of a farmer, Piers Murphy. He then stayed with a parish priest. During this period he came upon the gibbeted corpse of Patrick Devan, the leader of the murderers, a fact that so shocked him that he determined in later life to write an account of the Wildgoose Lodge murders.[7] William Carleton's account[8] of this incident is important in that it received widespread readership, having been published a number of times, and became the "standard" account of the affair, even among many of those living in the vicinity.[9] Many accepted it as being a true account of the atrocity, although Carleton wrote that it was fiction, based on a true event.[10]

In Carleton's account, the murders were perpetrated by an oath-bound rural secret society, the Ribbonmen, the leaders of which were portrayed as evil and demonic. The perpetrators were avenging the execution of three of their comrades hanged for an earlier raid on Wildgoose Lodge the previous April, following information given to the authorities by the owner of the house, Edward Lynch. According to Carleton's account, they showed no mercy in setting the house ablaze and preventing the inmates of the house from escaping the flames, and piked any would-be escapers, including a child, back into the flames.

Following some criticism of his account (for example, he had portrayed the family as being the only Protestant family in the parish, whereas in fact the victims at Wildgoose Lodge were all Catholics), Carleton made some changes to the next published version, in the Newry Advertiser in 1833.[11]

The social background

The land in this part of County Louth on the Monaghan border was good and well suited to tillage and grazing. Most of it belonged to the large Protestant landlords (Roden, Fortescue, Foster, Clermont, Filgate, and others) and it was farmed by tenant farmers, who might have farmed anything from a few acres to hundreds of acres. It should also be mentioned that the landlords were also the magistrates and members of the grand juries for the district, leaders of the yeomanry, and included the Governor and MPs of Louth among their ranks. There were also a number of flax growers and weavers in the area. Dependent upon all of these were the agricultural labourers.

During the Napoleonic wars the economy of the area did well, and exports to Britain steadily increased until 1815. However, from then on a recession set in, evictions and unemployment increased, prices rose and the number of poor in dire straits rose sharply. To add to the woes, the weather in 1816 was exceptionally bad, heavy rains prevented proper harvesting and the potato crop, upon which the poor in particular depended, was neither good nor plentiful. The ensuing poverty and unemployment led to disease and hunger. These factors added to the tensions that already existed between landlord and tenant with regard to grazing, rent disputes, evictions, land-grabbing, paying tithes and so on.[12] The vast majority of Catholics were still disenfranchised, so they could not try to solve their problems politically—even the (Protestant) Irish Parliament had been abolished in 1800.

The increasing poverty and desperation of the less-well-off in particular led to an increase in rural crime at this time. These included warnings to "land-grabbers", land-agents, informers and the like, while better-off farmers were burgled or attacked at night and money or arms stolen. Sometimes these crimes were the result of organised societies such as the Ribbonmen, but more often than not they were gangs composed of locals who saw no other way to protect their interests, or were done out of sheer desperation to avoid starvation.[13]

The increased lawlessness prompted the landlords in County Louth to take action, and most of the county came under a "Preservation Order" in 1816, which gave a free hand to magistrates and an influx of yeomanry to protect law and order. Meanwhile, the Governor, John Forster, and landlords such as Lord Roden put increasing pressure on the administration in Dublin Castle to take ever sterner measures to prevent the downfall of law and order and a repeat (as they saw it) of the events of 1798.

The prelude to the burning of Wildgoose Lodge was an attempted robbery that occurred there in April 1816. A group of men burst into the house, which was occupied by Edward Lynch and his son-in-law Rooney. They were looking for money and arms, which Lynch denied he had, and broke a loom. A fight started, during which Lynch and Rooney escaped to the loft, and the intruders departed. The following day Edward Lynch decided to report the crime, although according to a report from a parish priest, an apology and payment for the broken loom had been offered to him. Several men were arrested, of whom three were recognised by Lynch or Rooney as perpetrators (despite the darkness of the interior of the house). All had alibis given by family members, but were found guilty and hanged.

The following 29 October, Wildgoose Lodge was surrounded by about 100 men and set ablaze. The inmates, the Lynch and Rooney family members, and their three servants, died in the blaze. Following this unexpected event, the local community closed ranks. However, one witness was found who said she could identify some of those present – a Mrs. Risly, mother of one of the deceased servants. There was massive collusion between Dublin Castle administrators, a corrupt chief police magistrate, lawyers and landlords in Louth, to bring suspects to trial and prosecution. Although they had suspicions of other perpetrators, to make a case the investigating magistrates needed further witnesses. They found them in the form of two criminals, who, in return for payment, were prepared to swear that they could identify many of those present on the night of the burning.

The first trial to take place was of the alleged leader, a hedge-schoolteacher named Patrick Devan. He had fled to Dublin, where he was arrested. Despite promises of money and freedom from prosecution, he did not co-operate with the authorities. He pleaded not guilty and conducted his own defence, but the result was always a foregone conclusion, and he was found guilty, hanged and gibbeted.

The investigation ended with the trial and execution of a total of 18 men.

Remembrance

The Wildgoose Lodge Murders remains in the local folk memory. The lane rumoured to be the route taken by the attackers was known as "Hell Street" until well into the 20th century.[5] A play by Paul Macardle was staged in Dundalk in 1996 and 2011.[14] "Remembering Wildgoose Lodge" is a 2013–16 project by artist collective Gothicise working with locals in Reaghstown.[15] This play was later made into a film that was premiered in Dublin's Savoy Theatre in 2016.[16]

References and sources

- Notes

- Cross-reference 1909 Ordnance Survey map[1] with Google Maps.[2]

- Cross-reference 1909 Ordnance Survey map[1] with Google Maps.[3]

- Citations

- "25-inch map centred on (ruins of) Wildgoose Lodge". Mapviewer. Ordnance Survey Ireland. 1 June 1909. pp. Louth sheet 10–16+15. Archived from the original on 29 August 2012. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Aerial view centred on 53°55'36.8"N , 6°37'26.1"W". Google Maps. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Aerial view centred on 53°55'36.8"N , 6°37'26.1"W". Google Maps. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Murray (2005)

- McNally, Frank (10 January 2009). "An Irishman's Diary". The Irish Times. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Baile an Riabhaigh/Reaghstown". Placenames Database of Ireland. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Dooley (2007), p. 28

- Carleton (1830)

- Dooley (2007), p. 17

- Dooley (2007), p. 30-33

- Dooley (2007), p. 26

- Dooley (2007), p. 80-88

- Dooley (2007), p. 88-105

- Roddy, Margaret (12 January 2011). "Wild Goose Lodge events revisited". The Argus. Dundalk. Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- Fahey, Tracy. "Remembering Wildgoose Lodge: Gothic Trauma Recalled and Retold'". Retrieved 15 August 2015.

- "Wild Goose Lodge premiere". independent. Retrieved 28 July 2021.

- Sources

- Carleton, William (23 January 1830). "Confessions of a Reformed Ribbonman". Dublin Literary Gazette. Dublin (4–5): 49–50, 66–68. ISSN 2009-1648. Retrieved 15 August 2015. Reprinted as

- Carleton, William (1844). "Wildgoose Lodge". Traits and Stories of the Irish Peasantry. Vol. 2 (2nd ed.). pp. 349–362.

- Casey, Daniel J. (1974). "Wildgoose Lodge: The Evidence and the Lore". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 18 (2): 140–164. doi:10.2307/27729362. JSTOR 27729362.

- Casey, Daniel J. (1974). "Wildgoose Lodge: The Evidence and the Lore (Continued)". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 18 (3): 211–231. doi:10.2307/27729387. JSTOR 27729387.

- Dooley, Terence (2007). The Murders at Wildgoose Lodge. Four Courts Press. ISBN 978-1-84682-085-4.

- Murray, Raymond (2005). The Burning of Wildgoose Lodge. Armagh: Armagh Diocesan Society. ISBN 0-9511490-2-4.

- Ó Muirí, Réamonn (1986). "The Burning of Wildgoose Lodge: A Selection of Documents". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 21 (2): 117–147. doi:10.2307/27729616. JSTOR 27728752.

- Paterson, T. F. G. (1950). "The Burning of Wildgoose Lodge". Journal of the County Louth Archaeological and Historical Society. 12 (2): 159–180. doi:10.2307/27728752. JSTOR 27728752.

External links

- Book Club: The Murders at Wildgoose Lodge "The History Show", RTÉ Radio 1

- Wildgoose Lodge "Big Houses of Ireland" Ask About Ireland