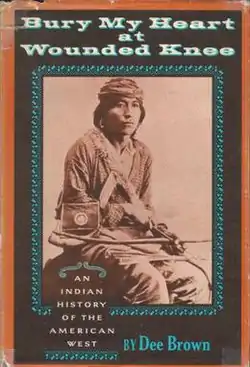

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West is a 1970 non-fiction book by American writer Dee Brown that covers the history of Native Americans in the American West in the late nineteenth century. The book expresses details of the history of American expansionism from a point of view that is critical of its effects on the Native Americans. Brown describes Native Americans' displacement through forced relocations and years of warfare waged by the United States federal government. The government's dealings are portrayed as a continuing effort to destroy the culture, religion, and way of life of Native American peoples.[1] Helen Hunt Jackson's 1881 book A Century of Dishonor is often considered a nineteenth-century precursor to Dee Brown's book.[2]

| |

| Author | Dee Brown |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | United States history, Native Americans |

| Genre | Non-fiction Historical |

| Publisher | New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston |

Publication date | 1970 |

| Media type | Print (hard & paperback) |

| Pages | 487 |

| ISBN | 0-03-085322-2 |

| OCLC | 110210 |

| 970.5 | |

| LC Class | E81 .B75 1971 |

Before the publication of Bury My Heart..., Brown had become well-versed in the history of the American frontier. Having grown up in Arkansas, he developed a keen interest in the American West, and during his graduate education at George Washington University and his career as a librarian for both the US Department of Agriculture and the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, he wrote numerous books on the subject.[3] Brown's works maintained a focus on the American West, but ranged anywhere from western fiction to histories to children's books. Many of Brown's books revolved around similar Native American topics, including his Showdown at Little Bighorn (1964) and The Fetterman Massacre (1974).[4]

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee was first published in 1970 to generally strong reviews. Published at a time of increasing American Indian activism, the book has never gone out of print and has been translated into 17 languages.[5] The title is taken from the final phrase of a twentieth-century poem titled "American Names" by Stephen Vincent Benét. The full quotation, "I shall not be there. I shall rise and pass. Bury my heart at Wounded Knee", appears at the beginning of Brown's book.[6] Although Benet's poem is not about the plight of Native Americans, Wounded Knee was the site of the last major attack by the US Army on Native Americans. It is also one of several potential locations for the site of Crazy Horse's burial.[7]

Synopsis

In the first chapter, Brown presents a brief history of the discovery and settlement of America, from 1492 to the Indian turmoil that began in 1860. He stresses the initially gentle and peaceable behavior of Indians toward Europeans, especially their lack of resistance to early colonial efforts at Europeanization. It was not until the further influx of European settlers, gradual encroachment, and eventual seizure of native lands by the "white man" that the Native peoples resisted.[1]: 1–12

Brown completes his initial overview by briefly describing incidents up to 1860 that involved American encroachment and Indian removal, beginning with the defeat of the Wampanoags and Narragansetts, Iroquois, and Cherokee Nations, as well as the establishment of the West as the "permanent Indian frontier" and the ultimate breaches of the frontier as a means to achieve Manifest Destiny.[1]: 3–12

In each of the following chapters, Brown provides an in-depth description of a significant post-1860 event in American Western expansion or Native American eradication, focusing in turn on the specific tribe or tribes involved in the event. In his narrative, Brown primarily discusses such tribes as the Navajo Nation, Santee Dakota, Hunkpapa Lakota, Oglala Lakota, Cheyenne, and Apache people. He touches more lightly upon the subjects of the Arapaho, Modoc, Kiowa, Comanche, Nez Perce, Ponca, Ute, and Minneconjou Lakota tribes.

Historical context

American Indian Movement

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee was published less than three years following the establishment of AIM, the American Indian Movement, formed in Minneapolis, Minnesota in 1968. AIM moved to promote modern Native American issues and to unite America's dividing Native American population, similar to the Civil Rights and Environmental Movements that gained support at that time. The publication of Brown's book came at the height of the American Indian Movement's activism. In 1969, AIM occupied Alcatraz Island for 19 months in hopes of reclaiming Native American land after the San Francisco Indian Center burned down.[8] In 1973, AIM and local Oglala and neighboring Sicangu Lakota took part in a 71-day occupation at Wounded Knee[9] in protest of the government of Pine Ridge Indian Reservation chairman Richard Wilson. This resulted in the death of two Indians and injury to a US Marshal.[10] The ensuing 1974 trial ended in the dismissal of all charges due to the uncovering of various incidents of government misconduct.[11]

Vietnam War

At the time of the publication of Brown's book, the United States was engaged in the Vietnam War. The actions of the United States Army in Vietnam were frequently criticized in the media and critics of Brown's narrative often drew comparisons between its contents and what was seen in the media. The primary comparison made was the similarity between the massacre of and atrocities against Native Americans in the late nineteenth century as portrayed by Brown's book and the 1968 massacre of hundreds of civilians in South Vietnam at My Lai for which twenty-five US Army troops were indicted. Native American author N. Scott Momaday, in his review of the narrative, agreed with the viability of the comparison, stating "Having read Mr. Brown, one has a better understanding of what it is that nags at the American conscience at times (to our everlasting credit) and of that morality which informs and fuses events so far apart in time and space as the massacres at Wounded Knee and My Lai."[5]

Thirty years later, in the foreword of a modern printing of the book by Hampton Sides, it is argued that My Lai had a powerful impact on the success of Brown's narrative, as "Bury My Heart landed on America's doorstep in the anguished midst of the Vietnam War, shortly after revelations of the My Lai massacre had plunged the nation into gnawing self-doubt. Here was a book filled with a hundred My Lais, a book that explored the dark roots of American arrogance while dealing a near-deathblow to our fondest folk myth."[12]

Reception

Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee received ultimately positive reviews upon its publication. Time magazine reviewed the book:

In the last decade or so, after almost a century of saloon art and horse operas that romanticized Indian fighters and white settlers, Americans have been developing a reasonably acute sense of the injustices and humiliations suffered by the Indians. But the details of how the West was won are not really part of the American consciousness. ... Dee Brown, Western historian and head librarian at the University of Illinois, now attempts to balance the account. With the zeal of an IRS investigator, he audits US history's forgotten set of books. Compiled from old but rarely exploited sources plus a fresh look at dusty Government documents, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee tallies the broken promises and treaties, the provocations, massacres, discriminatory policies and condescending diplomacy.[13]

The Native American author N. Scott Momaday, who won the Pulitzer Prize, noted that the book contains strong documentation of original sources, such as council records and first-hand descriptions. He stated that "it is, in fact, extraordinary on several accounts" and further complimented Brown's writing by saying that "the book is a story, whole narrative of singular integrity and precise continuity; that is what makes the book so hard to put aside, even when one has come to the end."[5]

Peter Farb reviewed the book in 1971 in The New York Review of Books: "The Indian wars were shown to be the dirty murders they were."[14] Other critics could not believe that the book was not written by a Native American and that Dee Brown was a white man, as the book's Native perspective felt so real.[4] Remaining on bestseller lists for over a year following its release in hardback, the book remains in print 40 years later. Translated into at least 17 languages, it has sold nearly four million copies and remains popular today.

Despite the book's widespread acceptance by journalists and the general public, scholars such as Francis Paul Prucha criticized it for lacking sources for much of the material, except for direct quotations. He also said that content was selected to present a particular point of view, rather than to be balanced, and that the narrative of government–Indian relations suffered from not being placed within the perspective of what else occurred in the government and the country at the time.[15] UC Davis history professor Ari Kelman also criticized the book for allegedly perpetuating the "Vanishing Indians" myth, stating "[a] hugely popular work of revisionist history intended to document a vibrant Indian past, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee instead reduced Indigenous history to declension, destruction and disappearance", also claiming "Dee Brown, no matter how sympathetic he intended his portrayal of Native history and peoples, recapitulated antiquated rhetoric about the disappearance of Indians."[16]

Brown was candid about his intention to present the history of the settlement of the West from the point of view of the Indians—"its victims," as he wrote. He noted, "Americans who have always looked westward when reading about this period should read this book facing eastward."[1]: xvi

Adaptations

Film

HBO Films produced a made-for-television film adaptation by the same title of Brown's book for the HBO television network. The film stars Adam Beach, Aidan Quinn, Anna Paquin, and August Schellenberg with a cameo appearance by late actor and former US Senator Fred Thompson as President Grant. It debuted on the HBO television network on May 27, 2007,[17] and covers roughly the last two chapters of Brown's book, focusing on the narrative of the Lakota tribes leading up to the death of Sitting Bull and the Massacre at Wounded Knee.[18] The film received 17 Primetime Emmy nominations and went on to win six awards, including the category of Outstanding Made For Television Movie.[19] It also garnered nominations for three Golden Globe Awards, two Satellite Awards, and one Screen Actors Guild Award.

Children's literature

The author of Lincoln's Last Days, Dwight Jon Zimmerman, adapted Brown's book for children in his work entitled The Saga of the Sioux. The narrative deals solely with the Sioux tribe as the representatives of the story told in Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee written from the perspective of the Sioux chiefs and warriors from 1860 to the events at the massacre at Wounded Knee. The book includes copious photographs, illustrations, and maps in support of the narrative and to appeal to its middle school demographic.[20]

See also

References

- Brown, Dee (2007). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 978-0-03-085322-7. OCLC 110210.

- Jackson, Helen Hunt (1985) [1881]. A Century of Dishonor: A Sketch of the United States Government's Dealings with Some of the Indian Tribes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-4209-4438-9.

- Brown, Dee (January 1995). "A Talk with Dee Brown" (DOC). Louis L'Amour Western Magazine (Interview). Interviewed by Dale L. Walker – via www.stgsigma.org. (Interview conducted in Fall 1994.)

- "Dee Brown (1908–2002)". Encyclopedia of Arkansas History & Culture. October 5, 2015. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- Momaday, N. Scott (March 7, 1971). "A History of the Indians of the United States". The New York Times. New York City. p. BR46.

- Benét, Stephen Vincent (1927). "American Names". poets.org. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- "Search For The Lost Trail of Crazy Horse". March 12, 2016. Archived from the original on March 12, 2016. Retrieved February 7, 2022.

- Wittstock, Laura Waterman; Salinas, Elaine J. "A Brief History of the American Indian Movement" (PDF). migizi.org. Minneapolis: MIGIZI Communications, Inc. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 13, 2013. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- Martin, Douglas (December 14, 2002). "Dee Brown, 94, Author Who Revised Image of West". The New York Times. New York City. Retrieved February 24, 2020.

- "History – Incident at Wounded Knee". usmarshals.gov. United States Marshals Service. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Conderacci, Greg (March 20, 1973). "At Wounded Knee, Is It War or PR?". The Wall Street Journal. New York City: Dow Jones & Company.

- Sides, Hampton (2007). Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 391–413. ISBN 978-0-03-085322-7. OCLC 110210.

- Sheppard, R. Z. (February 1, 1971). "The Forked-Tongue Syndrome". Time. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 1, 2007.

- Farb, Peter (December 16, 1971). "Indian Corn". The New York Review of Books.

- Prucha, Francis Paul (April 1972). "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, Review". The American Historical Review. American Historical Association. 77 (2): 589–590. doi:10.2307/1868839. JSTOR 1868839.

- Kelman, Ari (2023). "Chapter 3: Vanishing Indians". In Kruse, Kevin M.; Zelizer, Julian (eds.). Myth America: Historians Take On The Biggest Legends And Lies About Our Past. Basic Books. pp. 41–53. ISBN 978-1-5416-0139-0.

- "Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee". imdb.com. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved April 9, 2013.

- Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee, directed by Yves Simoneau (2007; Calgary, Alberta, Canada: HBO Films, 2007), DVD.

- "Bury My Heart At Wounded Knee". emmys.com. Retrieved January 6, 2017.

- Zimmerman, Dwight J. (2011). Saga of the Sioux: An Adaptation from Dee Brown's Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee. New York City: Henry Holt and Company.

External links

- Sterling Publishing's webpage: Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee