Códice de Roda

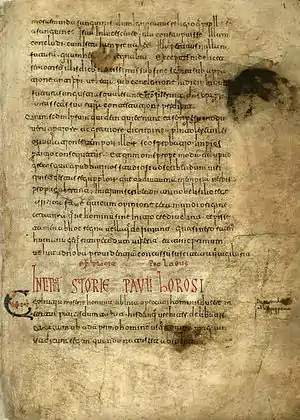

The Códice de Roda or Códice de Meyá (Roda or Meyá codex) is a medieval manuscript that represents a unique primary source for details of the 9th- and early 10th-century Kingdom of Navarre and neighbouring principalities. It is currently held in Madrid as Real Academia de la Historia MS 78.[1]

The codex is thought to date from the late 10th century, although there are additions from the 11th century, and it was compiled in Navarre, perhaps at Nájera, written in a Visigothic minuscule in several different hands with cursive marginal notes. It is 205 mm × 285 mm (8.1 in × 11.2 in), and contains 232 folios.[1] The manuscript appears to have been housed at Nájera in the 12th century, and later in the archives of the cathedral at Roda de Isábena at the end of the 17th century. In the next century, it was acquired by the prior of Santa María de Meyá, passing into private hands, after which only copies and derivative manuscripts were available to the scholarly community until the rediscovery of the original manuscript in 1928.[2]

The codex includes copies of well-known ancient and medieval texts, as well as unique material. The first two-thirds of the compilation reproduces a single work, Paulus Orosius' Seven Books of History Against the Pagans. Also notable are Isidore of Seville's History of the Goths, Vandals and Suebi, the Chronica prophetica,[3] the Historia de Melchisedech,[4] the Storia de Mahometh, the Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii and a genealogy of Jesus. Unique items include a list of Arab rulers and of the Christian kings of Asturias–León, Navarre and France; a chronicle of the Kingdom of Navarre; the Chronicle of Alfonso III; a necrology of the bishops of Pamplona; and the De laude Pampilone epistola. It also includes a chant in honour of an otherwise unknown Leodegundia Ordóñez, Queen of Navarre.[1][2]

Despite this diversity of material, the manuscript is perhaps best known for its genealogies of the dynasties ruling on both sides of the Pyrenees.[2][5] The genealogies in the Roda Codex have played a critical role in interpreting the scant surviving historical record of the dynasties covered. The family accounts span as many as five generations, ending in the first half of the 10th century. These include the Íñiguez and Jiménez rulers of Pamplona, the counties of Aragon, Sobrarbe, Ribagorza, Pallars, Toulouse and the duchy of Gascony. It has recently been suggested that these genealogies, reminiscent of the work of Ibn Hazm, were prepared in an Iberian Muslim context in the Ebro valley and passed to Navarre at the time the codex was compiled.[2][5]

Detailed contents

_del_C%C3%B3dice_de_Roda%252C_f._200v.jpg.webp)

The codex consists of the following texts, listed by their rubrics:

- fols 1r–155r: Paulus Orosius' Seven Books of History Against the Pagans[6]

- fols 156r–177r: Isidore of Seville's History of the Goths, Vandals and Suebi interspersed with his Chronica Maiora, with the history of the Vandals and Suebi (156r–159r) preceding the Chronica (159r–167r) and that of the Goths (167r–177r)[6][7]

- fol. 177r–v: Item in Alexander, an excerpt from the Apocalypse of Pseudo-Methodius[7][8]

- fols 178r–185v: Chronicle of Alfonso III, specifically, the version known as the Rotense[7][8]

- fol. 185v: Tultusceptru de libro domni Metobii[7][8]

- fols 186r–189v: Chronica prophetica, a group of Mozarabic traditions on Muslim rule in Spain and its eventual decline:[6][8]

- fol. 186r: Dicta de Ezecielis profeta[7]

- fol. 187r: Genealogia Sarracenorum[7]

- fols 187r–188r: Storia de Mahometh[8]

- fol. 188v: Ratio Sarracenorum de sua ingressione in Spania[7]

- fols 188v–189r: De Goti qui remanserint civitates Ispaniensis[7]

- fol. 189r: Hii sunt duces Arabum qui regnaverunt in Spania[7]

- fol. 189r: Item reges qui regnaberunt in Spania ex origine Ismaelitarum Beniumeie[7]

- fol. 189r–v: Remanent usque ad diem sancti Martini[9]

- fol. 189v: Nomina regum catholicorum Legionensium, a list of the kings of León[7][6]

- fol. 190r–v: De laude Pampilone epistola[7][10]

- fols 191r–194r: a group of Pyrenean genealogies:[6]

- fol. 191r–v: Ordo numerum regum Pampilonensium, the kings of Pamplona[7][10]

- fols 191v–192r: Item alia parte regum[7][10]

- fol. 192r–v: Item genera comitum Aragonensium, the counts of Aragon[7][10]

- fol. 192v: Item nomina comitum Paliarensium, the counts of Pallars[7][10]

- fol. 192v: Item nomina comitum Guasconiensium, the counts of Gascony[7][10]

- fol. 192v: Item nomina comitum Tolosanesium, the counts of Toulouse[7][10]

- fol. 193r–v: Nomina imperatorum qui christianis persequuti sunt, an account of the persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire, including a list of persecuting Roman emperors[6][11]

- fol. 193v: Nomina sanctorum qui in arcibo Toletano repperta sunt, an account of saints venerated in the diptychs of the church of Toledo[6][7][11]

- fol. 193v: Nomina Sebigotorum, a list of kings of the Visigoths[6][11]

- fol. 194r: De origine Romanorum[11]

- fol. 194r–v: De reges Francorum, a genealogy of the kings of France[7][10]

- fol. 195r: Agnoscamus generationes quod processerunt a Noe, a genealogy of Jesus[11][12]

- fol. 195r–v: De fabrica mundi, a Pseudo-Isidorean poem[7]

- fols 195v–196r: Isidore's De laude Spaniae, a poem in praise of Spain[12]

- fol. 196r–v: a series of texts drawn from the Chronica Albeldense under the rubrics Exquisitio Spaniaee, De septem miracula and De proprietatibus gentium[12]

- fol. 196v: De LXXII generationes linguarum plus a short statement that begins Item de uitulorum carnibus[12]

- fols 197r–198r: drawings of Babylon, Nineveh and Toledo[12] with the short text Historia de Octaviano et Septemsidero[13]

- fol. 198r: De laude Hispaniae, a poem in praise of Spain[7][12]

- fols 198v–207r: Genealogia Christi, with the text De orbe terre and a T and O map inserted at fols 200v–201r[12]

- fols 207v–208r: De sexta etate seculi[12]

- fols 208r–209r: Ordo annorum mundi[12]

- fol. 209r–v: De natiuitate et passione et resurrectione Domini[12]

- fols 209v–210r: De fine mundi[12][14]

- fol. 210v: De natura diaboli, an excerpt from Augustine's City of God[11]

- fol. 210v: two short texts entitled Interrogatio and De Christo[11]

- fol. 211r: De ordinibus angelorum[11]

- fol. 211r: Numerus legionum with a table[11]

- fol. 211v: Item sanctus Augustinus, an excerpt from Augustine's De Genesi ad litteram[11]

- fol. 211v: excerpts from Jerome and Isidore[11]

- fol. 212r: De sepulcro Domini, an excerpt from Smaragdus of Saint-Mihiel's Collectiones[11]

- fol. 212v: Unde factus est corpus de Adam[7]

- fol. 212v: Liber generationum[11]

- fol. 213v: De sex peccatis[7]

- fols 214r–215r: Item de cognitio ciuitas Ierusalem, an abridged version of the De situ terrae sanctae[7][11]

- fols 215r–216r: Item Dicta de Melcisethec[15]

- fols 216v–217r: De natibitate Sancte Marie, a text on the nativity of Mary drawn from the Gospel of James, is crossed out with a marginal note identifying it as apocryphal (apogrifum)[7][11]

- fols 217r–222r: two creedal formulae, Iterum de beata Maria (217r) and Item de sancta Trinitate (217v–222r)[7][11]

- fols 222r–225r: Conlatio Trinitatis sancti Agustini ad semetipsum[11]

- fols 225r–230v: Iterum dehinc domini Isidori dicit ad Trinitatem brebiter collecta, a treatise on the Trinity ascribed to Isidore[7][11]

- fol. 231r: De Pampilona[11]

- fol. 231r: Initium regnum Pampilonam[12]

- fol. 231v: Necrologium episcopale Pampilonense[12]

- fol. 232r–v: Versi domna Leodegundia regina, the earliest surviving European epithalamium with music[7][12]

References

- Citations

- García Villada (1928)

- Lacarra (1945)

- Wreglesworth (2010)

- Gil (1971), pp. 173–176.

- Lacarra (1992)

- Carlos Villamarín (2011), pp. 121–122

- Millares Carlo (1999), no. 210, at pp. 139–142

- Tischler 2021, pp. 288ff.

- Furtado (2016), p. 76–77

- Lacarra (1945), pp. 202–203

- Ruiz García (1997), pp. 398–399

- Furtado (2020), p. 66

- Gil (1971), pp. 165–170.

- Gil (1971), pp. 170–173.

- Gil (1971), pp. 173–176.

- Bibliography

- Helena de Carlos Villamarín, "El Códice de Roda (Madrid, BRAH 78) como compilación de voluntad historiografica", Edad Media. Rev. Hist., 12:119–142 (2011).

- Rodrigo Furtado, "The Chronica Prophetica in MS. Madrid, RAH Aem. 78," in L. Cristante and V. Veronesi, eds., Forme di accesso al sapere in età tardoantica e altomedievale, 6:75–100 (2016).

- Rodrigo Furtado, "Emulating Neighbours in Medieval Iberia around 1000: A Codex from La Rioja (Madrid, RAH, cód. 78)," in Kim Bergqvist, Kurt Villads Jensen and Anthony John Lappin, eds., Conflict and Collaboration in Medieval Iberia (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2020). pp. 43–72.

- Zacarías García Villada, "El códice de Roda recuperado," Revista de Filología Española 15:113–130 (1928).

- Juan Gil Fernández, "Textos olvidados del Códice de Roda," Habis 2:165–178 (1971).

- José María Lacarra. "Textos navarros del Códice de Roda," Estudios de Edad Media de la Corona de Aragón, 1:194–283 (1945). (article without accompanying genealogical charts)

- José María Lacarra. "Las Genealogías del Códice de Roda," Medievalia, 10:213–216 (1992).

- Agustín Millares Carlo, Corpus de códices visigóticos, Vol. 1: Estudios (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1999).

- Elisa Ruiz García, Catálogo de la sección de códices de la Real Academia de la Historia (Madrid, 1997).

- Matthias M. Tischler, "Spaces of ‘Convivencia’ and Spaces of Polemics Transcultural Historiography and Religious Identity in the Intellectual Landscape of the Iberian Peninsula, Ninth to Tenth Centuries", in Walter Pohl and Daniel Mahoney, eds., Historiography and Identity IV: Writing History Across Medieval Eurasia (Brepols, 2021), pp. 275–305.

- John Wreglesworth (2010). "Crónica profetica". In Dunphy, Graeme (ed.). Encyclopedia of the Medieval Chronicle. Leiden: Brill. p. 400. ISBN 90-04-18464-3.