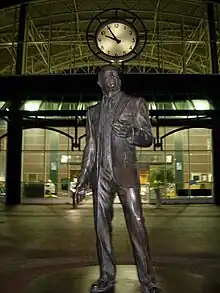

C. L. Dellums

Cottrell Laurence Dellums (January 3, 1900 – December 6, 1989) was an American labor activist and one of the organizers and leaders of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.

C. L. Dellums | |

|---|---|

Dellums c. 1920s | |

| Born | Cottrell Laurence Dellums January 3, 1900 |

| Died | December 6, 1989 (aged 89) |

| Relatives | Ron Dellums (nephew) |

Dellums worked as a porter for the Pullman Company from 1924 to 1927 and was discharged in part due to his open support of unionization. In 1929, Dellums was elected a vice president of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and became president in 1966. In the 1930s, Dellums was an officer in the NAACP Branch Office in Berkeley, California.

Born in Corsicana, Texas, he is the uncle of former Congressman and Mayor of Oakland Ron Dellums.

Before and during Sleeping Car Porters

Dellums “had chosen San Francisco as the most ideal place for a Negro to live in 1923.” Dellums also stated that the Bay Area's colleges and professional schools were an important attraction: "I wanted to be a lawyer and the University of California had the best law school.” Instead, however, Dellums went to work for the Southern Pacific railroad as a Pullman porter, where he gained the respect of his black coworkers and was ultimately elected International President of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters.[1]

Dellums became the standard bearer of a growing African American labor movement in Oakland, Richmond, and San Francisco in the aftermath of the war. As Dellums would later explain, “Negroes will have to pay for their own organization, their own fights, by their own funds as well as their own energy.” Dellums's Brotherhood and other Black railroad workers unions were built with “Negro leadership and Negro money” using the solidarity forged within sites of segregation to wage direct confrontations against racial discrimination.[2]

The union also became known for its social activism beyond the world of train porters. For many years, Dellums tackled such issues as police brutality and the miserable conditions in which black agricultural workers existed.[3] Dellums played a leading role in launching the Oakland Voters League (OVL) in the mid-1940s. This labor-civil rights coalition temporarily wrestled control of the Oakland City Council from the conservative Republican bloc that had dominated city politics for many years. Dellums with the OVL, drew their strength from building an organization and a new notion of political community among the city's multiracial working class.[2]

Fair Employment Practices Committee

A. Philip Randolph and Dellums were instrumental in opening war industries to African Americans by threatening a massive “March on Washington” if Roosevelt did not respond to black pleas for nondiscriminatory hiring in war industries. In response, Roosevelt issued an executive order establishing a Fair Employment Practice Committee (FEPC), which urged that defense plants be opened to African Americans.[4] Not all labor officials who favored fair employment laws supported putting the FEPC question on the ballot. Dellums opposed placing the question before voters. He later said:

“We should never set a precedent that we recognize that the people have a right to vote on anything they want to vote on. The rights I have been fighting for all my life, they are now called civil rights, I call human rights, God-given rights. White people have been using their majority and their control of the law enforcing agencies and firearms to prevent us from exercising our God-given rights…. We were never really asking white people to grant or give us any rights. Only to stop using their majority and power in preventing us from exercising our God-given rights.”[2]

Dellums would play a leading role in the subsequent fourteen-year effort to win approval of the FEPC measure within the state legislature, and he was eventually appointed by Governor Pat Brown to serve on the state's first Fair Employment Practices commission in 1960.[2] In 1964, Dellums and the California Fair Employment Practices Commission published “A Report on Oakland Schools” that provided a window into the structural problems within the district as a result of hiring discrimination being one of the biggest obstacles to making the Oakland Unified School District receptive to its growing black student body.[5]

References

- De Graaf, Lawrence Brooks., Kevin Mulroy, and Quintard Taylor. Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California. Los Angeles: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, 2001. Print. pg 186

- HoSang, Daniel. Racial Propositions: Ballot Initiatives and the Making of Postwar California. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 2010. Print.

- Reed, Ishmael. Blues City: A Walk in Oakland. New York: Crown Journeys, 2003. Print. Pg 34

- De, Graaf Lawrence Brooks., Kevin Mulroy, and Quintard Taylor. Seeking El Dorado: African Americans in California. Los Angeles: Autry Museum of Western Heritage, 2001. Print. pg 292

- Murch, Donna Jean. Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, 2010. Print. Pg 55

External links

- Conversation With Ron Dellums

- Dellums, C. L., International President of The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters and civil rights leader : oral history transcript / and related material, 1970-1973, University of California Libraries, 2006.