Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory

The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory (commonly abbreviated to CHC), is a psychological theory on the structure of human cognitive abilities. Based on the work of three psychologists, Raymond B. Cattell, John L. Horn and John B. Carroll, the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory is regarded as an important theory in the study of human intelligence. Based on a large body of research, spanning over 70 years, Carroll's Three Stratum theory was developed using the psychometric approach, the objective measurement of individual differences in abilities, and the application of factor analysis, a statistical technique which uncovers relationships between variables and the underlying structure of concepts such as 'intelligence' (Keith & Reynolds, 2010). The psychometric approach has consistently facilitated the development of reliable and valid measurement tools and continues to dominate the field of intelligence research (Neisser, 1996).

The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory is an integration of two previously established theoretical models of intelligence: the theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence (Gf-Gc) (Cattell, 1941; Horn 1965), and Carroll's three-stratum theory (1993), a hierarchical, three-stratum model of intelligence. Due to substantial similarities between the two theories they were amalgamated to form the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory (Willis, 2011, p. 45). However, some researchers, including John Carroll, have questioned not only the need but also the empirical basis for the theory.[1][2]

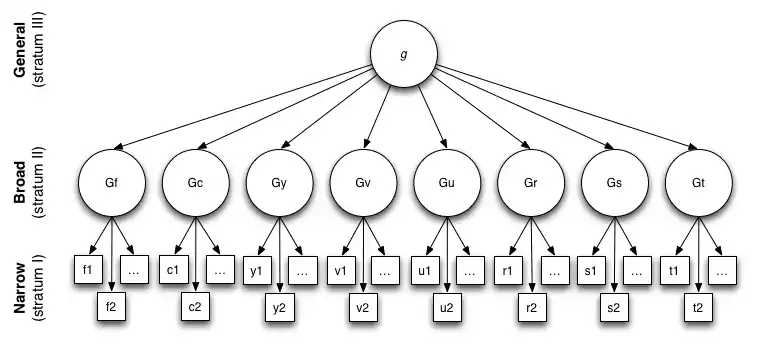

In the late 1990s the CHC model was expanded by McGrew, later revised with the help of Flanagan. Later extensions of the model are detailed in McGrew (2011)[3] and Schneider and McGrew (2012)[4] There are a fairly large number of distinct individual differences in cognitive ability, and CHC theory holds that the relationships among them can be derived by classifying them into three different strata: stratum I, "narrow" abilities; stratum II, "broad abilities"; and stratum III, consisting of a single "general ability" (or g).[5]

Today, the Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory is widely accepted as the most comprehensive and empirically supported theory of cognitive abilities, informing a substantial body of research and the ongoing development of IQ (Intelligence Quotient) tests (McGrew, 2005).[6]

Background

Development of the CHC model

The Cattell–Horn–Carroll theory of intelligence is a synthesis of Cattell and Horn's Gf-Gc model of fluid and crystallised intelligence and Carroll's Three Stratum Hierarchy (Sternberg & Kauffman, 1998). Awareness of the similarities between Cattel and Horn's Gf-Gc expanded model abilities and Carroll's Broad Stratum II abilities were highlighted at a meeting in 1985 concerning the revision of the Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery (Woodcock & Johnson, 1989). At this meeting Horn presented the Gf-Gc theory to several prominent figures in intelligence testing, including John B. Carroll (McGrew, 2005). Carroll was already a vocal proponent of the Cattell-Horn theory, stating in 1993 that the Gf-Gc model "appears to offer the most well-founded and reasonable approach to an acceptable theory of the structure of cognitive abilities" (Carroll, 1993, p. 62). This fortuitous meeting was the starting point for the integration of the two theories. The integration of the two theories evolved through a series of bridging events that occurred over two decades. Although there are many similarities between the two models, Horn consistently and unyieldingly argued against a single general ability g factor (McGrew, 2005, p. 174). Charles Spearman first proposed the existence of the g-factor (also known as general intelligence) in the early 20th century after discovering significant positive correlations between children's scores in seemingly unrelated academic subjects (Spearman, 1904). Unlike Horn, Carroll argued that evidence for a single 'general' ability was overwhelming, and insisted that g was essential to a theory of human intelligence.[7][8]

Cattell and Horn's Gf–Gc Model

Raymond B. Cattell (20 March 1905 – 2 February 1998) was the first to propose a distinction between "fluid intelligence" (Gf) and "crystallised intelligence" (Gc). Charles Spearman's s factors are considered a prequel to this idea (Spearman, 1927), along with Thurstone's theory of Primary Mental Abilities. By 1991, John Horn, a student of Cattell's, had expanded the Gf-Gc model to include 8 or 9 broad abilities.

Fluid intelligence refers to quantitative reasoning, processing ability, adaptability to new environments and novel problem solving. Crystallised intelligence (Gc) refers to the accumulation of knowledge (general, procedural and declarative). Gc tasks include problem solving with familiar materials and culture-fair tests of general knowledge and vocabulary. Gf and Gc are both factors of g (general intelligence). Though distinct, there is interaction, as fluid intelligence is a determining factor in the speed with which crystallised knowledge is accumulated (Cattell, 1963). Crystallised intelligence is known to increase with age as we accumulate knowledge throughout the lifespan. Fluid processing ability reaches a peak around age 20, then declines steadily. Recent research has explored the idea that training on working memory tasks can transfer to improvements in fluid intelligence. (Jaeggi, 2008).[9] This idea did not hold under further scrutiny (Melby-Lervåg, Redick, & Hulme, 2016).[10]

Carroll's three-stratum hierarchy

The American psychologist John B. Carroll (June 5, 1916 – July 1, 2003) made substantial contributions to psychology, psychometrics and educational linguistics. In 1993, Carroll published Human Cognitive Abilities: A Survey of Factor-Analytic Studies, in which he presented 'A Theory of Cognitive Abilities: The Three-Stratum Theory'. Carroll had re-analysed data-sets from 461 classic factor analytic studies of human cognition, distilling the results into 800 pages, thus providing a solid foundation for future research in human intelligence (Carroll, 1993, p. 78-91).

Carroll's three-stratum theory presented three levels of cognition: narrow abilities (stratum I), broad abilities (stratum II) and general abilities (stratum III).

Abilities

Broad and narrow abilities

The broad abilities are:[11]

- Comprehension-Knowledge (Gc): includes the breadth and depth of a person's acquired knowledge, the ability to communicate one's knowledge, and the ability to reason using previously learned experiences or procedures.

- Fluid reasoning (Gf): includes the broad ability to reason, form concepts, and solve problems using unfamiliar information or novel procedures.

- Quantitative knowledge (Gq): is the ability to comprehend quantitative concepts and relationships and to manipulate numerical symbols.[11]

- Reading & Writing Ability (Grw): includes basic reading and writing skills.

- Short-Term Memory (Gsm): is the ability to apprehend and hold information in immediate awareness and then use it within a few seconds.

- Long-Term Storage and Retrieval (Glr): is the ability to store information and fluently retrieve it later in the process of thinking.

- Visual Processing (Gv): is the ability to perceive, analyze, synthesize, and think with visual patterns, including the ability to store and recall visual representations.

- Auditory Processing (Ga): is the ability to analyze, synthesize, and discriminate auditory stimuli, including the ability to process and discriminate speech sounds that may be presented under distorted conditions.[11]

- Processing Speed (Gs): is the ability to perform automatic cognitive tasks, particularly when measured under pressure to maintain focused attention.

A tenth ability, Decision/Reaction Time/Speed (Gt), is considered part of the theory, but is not currently assessed by any major intellectual ability test, although it can be assessed with a supplemental measure such as a continuous performance test.[12]

- Decision/Reaction Time/Speed (Gt): reflects the immediacy with which an individual can react to stimuli or a task (typically measured in seconds or fractions of seconds; not to be confused with Gs, which typically is measured in intervals of 2–3 minutes).

McGrew proposes a number of extensions to CHC theory, including Domain-specific knowledge (Gkn), Psychomotor ability (Gp), and Psychomotor speed (Gps). In addition, additional sensory processing abilities are proposed, including tactile (Gh), kinesthetic (Gk), and olfactory (Go).[3]

The narrow abilities are:

| Quantitative knowledge | Reading & writing | Comprehension-Knowledge | Fluid reasoning | Short-term memory | Long term storage and retrieval | Visual processing | Auditory processing | Processing speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mathematical knowledge | Reading decoding | General verbal information | Inductive reasoning | Memory span | Associative memory | Visualization | Phonetic coding | Perceptual speed |

| Mathematical achievement | Reading comprehension | Language development | General sequential reasoning | Working memory capacity | Meaningful memory | Speeded rotation | Speech sound discrimination | Rate of test taking |

| Reading speed | Lexical knowledge | Piagetian reasoning | Free-recall memory | Closure speed | Resistance to auditory stimulus distortion | Number facility | ||

| Spelling ability | Listening ability | Quantitative reasoning | Ideational fluency | Flexibility of closure | Memory for sound patterns | Reading speed/fluency | ||

| English usage | Communication ability | Speed of reasoning | Associative fluency | Visual memory | Maintaining and judging rhythms | Writing speed/fluency | ||

| Writing ability | Grammatical sensitivity | Expressional fluency | Spatial scanning | Musical discrimination and judgement | ||||

| Writing speed | Oral production & fluency | Originality | Serial perceptual integration | Absolute pitch | ||||

| Cloze ability | Foreign language aptitude | Naming facility | Length estimation | Sound localization | ||||

| Word fluency | Perceptual illusions | Temporal tracking | ||||||

| Figural fluency | Perceptual alternations | |||||||

| Figural flexibility | Imagery | |||||||

| Learning ability |

Model tests

Many tests of cognitive ability have been classified using the CHC model and are described in The Intelligence Test Desk Reference (ITDR) (McGrew & Flanagan, 1998). CHC theory is particularly relevant to school psychologists for psychoeducational assessment. 5 of the 7 major tests of intelligence have changed to incorporate CHC theory as their foundation for specifying and operationalizing cognitive abilities/processes. Since even all modern intellectual test instruments fail to effectively measure all 10 broad stratum abilities an alternative method of cognitive assessment and interpretation called Cross Battery Assessment (XBA; Flanagan, Ortiz, Alfonso, & Dynda, 2008) was developed. However, the veracity of this approach to assessment and interpretation has been criticized in the research literature as statistically flawed.[13]

Other related issues

Consistent with the evolving nature of the theory, the Cattell-Horn-Carroll framework remains "an open-ended empirical theory to which future tests of as yet unmeasured or unknown abilities could possibly result in additional factors at one or more levels in Carroll's hierarchy".[14] There is still some debate on the broad (stratum II) abilities, and the narrow (stratum I) abilities, and these remain open for refinement.

MacCallum (2003, p. 113–115) highlighted the need to recognize the limitations of artificial measurement tools built upon mathematical models: "Simply put, our models are implausible if taken as exact or literal representations of real world phenomena. They cannot capture the complexity of the real world which they purport to represent. At best, they can provide an approximation of the real world that has some substantive meaning and some utility."

See also

- Fluid and crystallized intelligence for Gf-Gc theory

Notes

- Wasserman, John D. (2019-07-03). "Deconstructing CHC". Applied Measurement in Education. 32 (3): 249–268. doi:10.1080/08957347.2019.1619563. ISSN 0895-7347. S2CID 218638914.

- Geisinger, Kurt F. (2019-07-03). "Empirical Considerations on Intelligence Testing and Models of Intelligence: Updates for Educational Measurement Professionals". Applied Measurement in Education. 32 (3): 193–197. doi:10.1080/08957347.2019.1619564. ISSN 0895-7347.

- McGrew, K. http://www.iapsych.com/CHCPP/CHCPP.HTML Retrieved 12/6/2011.

- Schneider, W. J., & McGrew, K. S. (2012). The Cattell-Horn-Carroll model of intelligence. In D. Flanagan & P. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (3rd ed., pp. 99–144). New York: Guilford.

- Flanagan, D. P., & Harrison, P. L. (2005). Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues. (2nd Edition). New York, NY: The Guilford Press

- McGrew, K. S. (2005). The Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory of cognitive abilities: Past, present, and future. In D. P. Flanagan, J. L. Genshaft, & P. L. Harrison (Eds.), Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues (pp.136–182). New York: Guilford.

- J. B. Carroll (1993), Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies, Cambridge University Press, New York, NY, USA.

- J. B. Carroll (1997), "The three-stratum theory of cognitive abilities" in D. P. Flanagan, J. L. Genshaft et al., Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues, Guilford Press, New York, NY, USA.

- Jaeggi, Susanne M.; Buschkuehl, Martin; Jonides, John; Perrig, Walter J. (2008). "Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (19): 6829–33. Bibcode:2008PNAS..105.6829J. doi:10.1073/pnas.0801268105. JSTOR 25461885. PMC 2383929. PMID 18443283.

- Melby-Lervåg, Monica; Redick, Thomas S.; Hulme, Charles (2016). "SAGE Journals: Your gateway to world-class journal research". Perspectives on Psychological Science. 11 (4): 512–534. doi:10.1177/1745691616635612. PMC 4968033. PMID 27474138.

- Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C. (2007). Essentials of cross-battery assessment. (2nd Edition). New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc

- "CHC Theory". Archived from the original on 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2016-06-11.

- McGill, Ryan J.; Styck, Kara M.; Palomares, Ronald S.; Hass, Michael R. (August 2016). "Critical Issues in Specific Learning Disability Identification: What We Need to Know About the PSW Model". Learning Disability Quarterly. 39 (3): 159–170. doi:10.1177/0731948715618504. ISSN 0731-9487. S2CID 148522903.

- Jensen, Arthur R (January 2004). "Obituary". Intelligence. 32 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2003.10.001.

References

- Carroll, J.B. (1993). Human cognitive abilities: A survey of factor-analytic studies. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Carroll, J. B. (2003). The higher-stratum structure of cognitive abilities: Current evidence supports g and about ten broad factors. In H. Nyborg (Ed.), The scientific study of general intelligence: Tribute to Arthur R. Jensen (pp. 5–22). San Diego: Pergamon.

- Cattell, R. B. (1941). Some theoretical issues in adult intelligence testing. Psychological Bulletin, 38, 592.

- Cattell, R. B. (1963). Theory of fluid and crystallized intelligence: A critical experiment. Journal of educational psychology, 54(1), 1.

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). (Ed.), Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally.

- Child, D. (2006). The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd edition. Bloomsbury Academic Press.

- Cohen, R. J., & Swerdlik, M. E. (2004). Psychological testing and assessment. Chicago, IL: McGraw-Hill (6th ed.)

- Flanagan, D. P., McGrew, K. S., & Ortiz, S. O. (2000). The Wechsler Intelligence Scales and Gf-Gc theory: A contemporary approach to interpretation. Allyn & Bacon.

- Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., & Alfonso, V. C. (2013). Essentials of cross-battery assessment (3rd edition). New York: Wiley.

- Flanagan, D. P., Ortiz, S. O., Alfonso, V. C., & Dynda, A. M. (2008). Best practices in cognitive assessment. Best Practices in School Psychology V, Bethesda: NASP Publications.

- Gustafsson, J. E., & Undheim, J. O. (1996). Individual differences in cognitive functions. In D.C. Berliner & R. C. Calfee (Eds.), Handbook of educational psychology (pp. 186–242). New York: Macmillan Library Reference USA.

- Horn, J. L. (1965). Fluid and crystallized intelligence: A factor analytic and developmental study of the structure among primary mental abilities. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Illinois, Champaign.

- Horn, J. L., Donaldson, G., & Engstrom, R. (1981). Apprehension, memory, and fluid intelligence decline in adulthood. Research on Aging, 3(1), 33-84.

- Keith, T. Z., & Reynolds, M. R. (2010). Cattell–Horn–Carroll abilities and cognitive tests: What we've learned from 20 years of research. Psychology in the Schools, 47(7), 635-650.

- MacCallum, R. C. (2003). Working with imperfect models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 38(1), 113-139.

- McGrew, K. & Flanagan, D. (1998). The Intelligence Test Desk Reference: Gf-Gc cross-battery assessment. Allyn & Bacon.

- McGrew, K. S. (2005). The Cattell-Horn-Carroll Theory of Cognitive Abilities. In D. P. Flanagan & P. L. Harrison (Eds.). (2012). Contemporary intellectual assessment: Theories, tests, and issues. (pp. 151–179). New York: Guilford Press.

- Neisser, U., Boodoo, G., Bouchard Jr, T. J., Boykin, A. W., Brody, N., Ceci, S. J., ... & Urbina, S. (1996). Intelligence: knowns and unknowns. American psychologist, 51(2), 77.

- Sheehan, E., Tsai, N., Duncan, G. J., Buschkuehl, M., & Jaeggi, S. M. (2015). Improving fluid intelligence with training on working memory: a meta-analysis. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 22(2), 366-377.

- Spearman, C. (1904). " General Intelligence," objectively determined and measured. The American Journal of Psychology, 15(2), 201-292.

- Spearman, C. (1927). The abilities of man: Their nature and measurement. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Sternberg, R. J., & Kaufman, J. C. (1998). Human abilities. Annual review of psychology, 49(1), 479-502.

- Willis, J. O., Dumont, R., & Kaufman, A. S. Factor-analytic models of intelligence. In Sternberg, R. J., & Kaufman, S. B. (Eds.). (2011). The Cambridge handbook of intelligence. (pp. 39–57). Cambridge University Press.

- Woodcock, R. W, and Johnson M. B. (1989). Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery-Revised. Chicago, IL: Riverside Publishing.

Further reading

- Gregory, Robert J. (2011). Psychological Testing: History, Principles, and Applications (Sixth ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 978-0-205-78214-7.

- Kaufman, Alan S. (2009). IQ Testing 101. New York: Springer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8261-0629-2.

- Tucker, William H. (2009). The Cattell Controversy: Race, Science, and Ideology. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-03400-8.

- Scott Jaschik (March 20, 2009). "The Cattell Controversy". Inside Higher Ed. Archived from the original on 2011-12-05.

- Newton, J. H., & McGrew, K. S. (2010). Introduction to the special issue: Current research in Cattell–Horn–Carroll–based assessment. Psychology in the Schools, 47(7), 621-634.