Ultramarine

Ultramarine is a deep blue color pigment which was originally made by grinding lapis lazuli into a powder.[2] Its lengthy grinding and washing process makes the natural pigment quite valuable—roughly ten times more expensive than the stone it comes from and as expensive as gold.[3][4]

| Ultramarine | |

|---|---|

Ultramarine pigment | |

| Hex triplet | #120A8F |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (18, 10, 143) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (244°, 93%, 56%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (17, 65, 266°) |

| Source | ColorHexa[1] |

| ISCC–NBS descriptor | Deep blue |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

The name ultramarine comes from the Latin ultramarinus. The word means "beyond the sea", as the pigment was imported by Italian traders during the 14th and 15th centuries from mines in Afghanistan.[5][6] Much of the expansion of ultramarine can be attributed to Venice which historically was the port of entry for lapis lazuli in Europe.

Ultramarine was the finest and most expensive blue used by Renaissance painters. It was often used for the robes of the Virgin Mary and symbolized holiness and humility. It remained an extremely expensive pigment until a synthetic ultramarine was invented in 1826.[7]

Ultramarine is a permanent pigment when under ideal preservation conditions. Otherwise, it is susceptible to discoloration and fading.[8]

Structure

The pigment consists primarily of a zeolite-based mineral containing small amounts of polysulfides. It occurs in nature as a proximate component of lapis lazuli containing a blue cubic mineral called lazurite. In the Colour Index International, the pigment of ultramarine is identified as P. Blue 29 77007.[9]

The major component of lazurite is a complex sulfur-containing sodium-silicate (Na8–10Al6Si6O24S2–4), which makes ultramarine the most complex of all mineral pigments.[10] Some chloride is often present in the crystal lattice as well. The blue color of the pigment is due to the S−

3 radical anion, which contains an unpaired electron.[11]

Visual properties

The best samples of ultramarine are a uniform deep blue while other specimens are of paler color.[12]

Particle size distribution has been found to vary among samples of ultramarine from various workshops. Numerous grinding techniques used by painters have resulted in different pigment/medium ratios and particle size distributions. The grinding and purification process results in pigment with particles of various geometries. Different grades of pigment may have been used for different areas in a painting, a characteristic that is sometimes used in art authentication.[13]

Shades and variations

| Electric Ultramarine | |

|---|---|

| Hex triplet | #3F00FF |

| sRGBB (r, g, b) | (63, 0, 255) |

| HSV (h, s, v) | (255°, 100%, 100%) |

| CIELChuv (L, C, h) | (35, 133, 268°) |

| Source | Maerz and Paul[14] |

| B: Normalized to [0–255] (byte) | |

International Klein Blue (IKB)

International Klein Blue a deep blue hue first mixed by the French artist Yves Klein.[15]

Electric

Electric ultramarine is the tone of ultramarine that is halfway between blue and violet on the RGB (HSV) color wheel, the expression of the HSV color space of the RGB color model.[16]

Production

Natural production

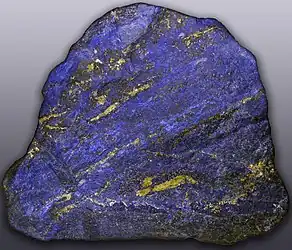

Historically, lapis lazuli stone was mined in Afghanistan and shipped overseas to Europe.[5]

At the beginning of the 13th century, a method to produce ultramarine from lapis lazuli was introduced and later described by Cennino Cennini in the 15th century. This process consisted of grinding the lapis lazuli mineral, mixing the ground material with melted wax, resins, and oils, wrapping the resulting mass in a cloth, and then kneading it in a dilute lye solution, a potassium carbonate solution prepared by combining wood ash with water. The blue lazurite particles collect at the bottom of the pot, while the colorless crystalline material and other impurities remain at the top. This process was performed at least three times, with each successive extraction generating a lower quality material. The final extraction, consisting largely of colorless material as well as a few blue particles, brings forth ultramarine ash which is prized as a glaze for its pale blue transparency.[17] This extensive process was specific to ultramarine because the mineral it comes from has a combination of both blue and colorless pigments. If an artist were to simply grind and wash lapis lazuli, the resulting powder would be a greyish-blue color that lacks purity and depth of color since lapis lazuli contains a high proportion of colorless material.[18]

Although the lapis lazuli stone itself is relatively inexpensive, the lengthy process of pulverizing, sifting, and washing to produce ultramarine makes the natural pigment quite valuable and roughly ten times more expensive than the stone it comes from. The high cost of the imported raw material and the long laborious process of extraction combined has been said to make high-quality ultramarine as expensive as gold.[3][4]

Synthetic production

In 1990, an estimated 20,000 tons of ultramarine were produced industrially. The raw materials used in the manufacture of synthetic ultramarine are the following:

- white kaolin,

- anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4),

- anhydrous sodium carbonate (Na2CO3),

- powdered sulfur,

- powdered charcoal or relatively ash-free coal, or colophony in lumps.[19]

The preparation is typically made in steps:

- The first part of the process takes place at 700 to 750 °C in a closed furnace, so that sulfur, carbon and organic substances give reducing conditions. This yields a yellow-green product sometimes used as a pigment.

- In the second step, air or sulfur dioxide at 350 to 450 °C is used to oxidize sulfide in the intermediate product to S2 and Sn chromophore molecules, resulting in the blue (or purple, pink or red) pigment.[20]

- The mixture is heated in a kiln, sometimes in brick-sized amounts.

- The resultant solids are then ground and washed, as is the case in any other insoluble pigment's manufacturing process; the chemical reaction produces large amounts of sulfur dioxide. (Flue-gas desulfurization is thus essential to its manufacture where SO2 pollution is regulated.)

Ultramarine poor in silica is obtained by fusing a mixture of soft clay, sodium sulfate, charcoal, sodium carbonate, and sulfur. The product is at first white, but soon turns green "green ultramarine" when it is mixed with sulfur and heated. The sulfur burns, and a fine blue pigment is obtained. Ultramarine rich in silica is generally obtained by heating a mixture of pure clay, very fine white sand, sulfur, and charcoal in a muffle furnace. A blue product is obtained at once, but a red tinge often results. The different ultramarines—green, blue, red, and violet—are finely ground and washed with water.[19]

Synthetic ultramarine is a more vivid blue than natural ultramarine, since the particles in synthetic ultramarine are smaller and more uniform than the particles in natural ultramarine and therefore diffuse light more evenly.[21] Its color is unaffected by light nor by contact with oil or lime as used in painting. Hydrochloric acid immediately bleaches it with liberation of hydrogen sulfide. Even a small addition of zinc oxide to the reddish varieties especially causes a considerable diminution in the intensity of the color.[19] Modern, synthetic ultramarine blue is a non-toxic, soft pigment that does not need much mulling to disperse into a paint formulation.[22]

Lapis lazuli specimen (rough), Afghanistan

Lapis lazuli specimen (rough), Afghanistan Natural ultramarine

Natural ultramarine Synthetic ultramarine blue

Synthetic ultramarine blue Synthetic ultramarine violet

Synthetic ultramarine violet

Structure and classification

Ultramarine is the aluminosilicate zeolite with a sodalite structure. Sodalite consists of interconnected aluminosilicate cages. Some of these cages contain polysulfide (Sn−

x) groups that are the chromophore (color centre). The negative charge on these ions is balanced by Na+

ions that also occupy these cages.[11]

The chromophore is proposed to be S−

4 or S4.[11]

History

Antiquity and Middle Ages

The name derives from Middle Latin ultramarinus, literally "beyond the sea" because it was imported from Asia by sea.[5] In the past, it has also been known as azzurrum ultramarine, azzurrum transmarinum, azzuro oltramarino, azur d'Acre, pierre d'azur, Lazurstein. The current terminology for ultramarine includes natural ultramarine (English), outremer lapis (French), Ultramarin echt (German), oltremare genuino (Italian), and ultramarino verdadero (Spanish). The first recorded use of ultramarine as a color name in English was in 1598.[23]

The first noted use of lapis lazuli as a pigment can be seen in 6th and 7th-century AD paintings in Zoroastrian and Buddhist cave temples in Afghanistan, near the most famous source of the mineral. Lapis lazuli has been identified in Chinese paintings from the 10th and 11th centuries, in Indian mural paintings from the 11th, 12th, and 17th centuries, and on Anglo-Saxon and Norman illuminated manuscripts from c.1100.[4]

Ancient Egyptians used lapis lazuli in solid form for ornamental applications in jewelry, however, there is no record of them successfully formulating lapis lazuli into paint.[24] Archaeological evidence and early literature reveal that lapis lazuli was used as a semi-precious stone and decorative building stone from early Egyptian times. The mineral is described by the classical authors Theophrastus and Pliny. There is no evidence that lapis lazuli was used ground as a painting pigment by ancient Greeks and Romans. Like ancient Egyptians, they had access to a satisfactory blue colorant in the synthetic copper silicate pigment, Egyptian blue.[4]

Renaissance

.jpg.webp) The Wilton Diptych (1395–1399) is an example of the use of ultramarine in 14th-century England

The Wilton Diptych (1395–1399) is an example of the use of ultramarine in 14th-century England The blue robes of the Virgin Mary by Masaccio (1426) were painted with ultramarine

The blue robes of the Virgin Mary by Masaccio (1426) were painted with ultramarine Pietro Perugino economized on this painting of the Virgin Mary (about 1500) by using azurite for the underpainting of the robe, then adding a layer of ultramarine on top

Pietro Perugino economized on this painting of the Virgin Mary (about 1500) by using azurite for the underpainting of the robe, then adding a layer of ultramarine on top Titian made dramatic use of ultramarine in the sky and draperies of Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523)

Titian made dramatic use of ultramarine in the sky and draperies of Bacchus and Ariadne (1520–1523)

Venice was central to both the manufacturing and distribution of ultramarine during the early modern period. The pigment was imported by Italian traders during the 14th and 15th centuries from mines in Afghanistan.[5][6] Other European countries employed the pigment less extensively than in Italy; the pigment was not used even by wealthy painters in Spain at that time.[25]

During the Renaissance, ultramarine was the finest and most expensive blue that could be used by painters. Color infrared photogenic studies of ultramarine in 13th and 14th-century Sienese panel paintings have revealed that historically, ultramarine has been diluted with white lead pigment in an effort to use the color more sparingly given its high price.[26] The 15th century artist Cennino Cennini wrote in his painters' handbook: "Ultramarine blue is a glorious, lovely and absolutely perfect pigment beyond all the pigments. It would not be possible to say anything about or do anything to it which would not make it more so."[27] Natural ultramarine is a difficult pigment to grind by hand, and for all except the highest quality of mineral, sheer grinding and washing produces only a pale grayish blue powder.[28]

The pigment was most extensively used during the 14th through 15th centuries, as its brilliance complemented the vermilion and gold of illuminated manuscripts and Italian panel paintings. It was valued chiefly on account of its brilliancy of tone and its inertness in opposition to sunlight, oil, and slaked lime. It is, however, extremely susceptible to even minute and dilute mineral acids and acid vapors. Dilute HCl, HNO3, and H2SO4 rapidly destroy the blue color, producing hydrogen sulfide (H2S) in the process. Acetic acid attacks the pigment at a much slower rate than mineral acids.

Ultramarine was only used for frescoes when it was applied secco because frescoes' absorption rate made its use cost prohibitive. The pigment was mixed with a binding medium like egg to form a tempera and applied over dry plaster, such as in Giotto di Bondone's frescos in the Cappella degli Scrovegni or the Arena Chapel in Padua.

European artists used the pigment sparingly, reserving their highest quality blues for the robes of Mary and the Christ child, possibly in an effort to show piety, spending as a means of expressing devotion. As a result of the high price, artists sometimes economized by using a cheaper blue, azurite, for under painting. Most likely imported to Europe through Venice, the pigment was seldom seen in German art or art from countries north of Italy. Due to a shortage of azurite in the late 16th and 17th century, the price for the already-expensive ultramarine increased dramatically.[29]

17th and 18th centuries

Sassoferrato's depiction of the Blessed Virgin Mary, The Virgin in Prayer, c. 1654. Her blue cloak is painted in ultramarine.[30]

Sassoferrato's depiction of the Blessed Virgin Mary, The Virgin in Prayer, c. 1654. Her blue cloak is painted in ultramarine.[30] Girl with a Pearl Earring, by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1665)

Girl with a Pearl Earring, by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1665) Lady Standing at a Virginal, by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1675)

Lady Standing at a Virginal, by Johannes Vermeer (c. 1675)

Johannes Vermeer made extensive use of ultramarine in his paintings. The turban of the Girl with a Pearl Earring is painted with a mixture of ultramarine and lead white, with a thin glaze of pure ultramarine over it.[31] In Lady Standing at a Virginal, the young woman's dress is painted with a mixture of ultramarine and green earth, and ultramarine was used to add shadows in the flesh tones.[32] Scientific analysis by the National Gallery in London of Lady Standing at a Virginal showed that the ultramarine in the blue seat cushion in the foreground had degraded and become paler with time; it would have been a deeper blue when originally painted.[33]

19th century (invention of synthetic ultramarine)

The beginning of the development of artificial ultramarine blue is known from Goethe. In about 1787, he observed the blue deposits on the walls of lime kilns near Palermo in Sicily. He was aware of the use of these glassy deposits as a substitute for lapis lazuli in decorative applications. He did not mention if it was suitable to grind for a pigment.[34][35]

In 1814, Tassaert observed the spontaneous formation of a blue compound, very similar to ultramarine, if not identical with it, in a lime kiln at St. Gobain.[36] In 1824, this caused the Societé pour l'Encouragement d'Industrie to offer a prize for the artificial production of the precious color. Processes were devised by Jean Baptiste Guimet (1826) and by Christian Gmelin (1828), then professor of chemistry in Tübingen. While Guimet kept his process a secret, Gmelin published his, and became the originator of the "artificial ultramarine" industry.[37][19]

Permanence

Easel paintings and illuminated manuscripts have revealed natural ultramarine in a perfect state of preservation even though the art may be several centuries old. In general, ultramarine is a permanent pigment. Although it is a sulfur-containing compound from which sulfur is readily emitted as H2S, historically, it has been mixed with lead white with no reported occurrences of the lead pigment blackening to become lead sulfide.[8]

A plague known as "ultramarine sickness" has occasionally been observed among ultramarine oil paintings as a grayish or yellowish gray discoloration of the paint surface. This can occur with artificial ultramarine that is used industrially. The cause of this has been debated among experts, however, potential causes include atmospheric sulfur dioxide and moisture, acidity of an oil- or oleo-resinous paint medium, or slow drying of the oil during which time water may have been absorbed, creating swelling, opacity of the medium, and therefore whitening of the paint film.[8]

Both natural and artificial ultramarine are stable to ammonia and caustic alkalis in ordinary conditions. Artificial ultramarine has been found to fade when in contact with lime when it is used to color concrete or plaster. These observations have led experts to speculate if the natural pigment’s fading may be the result of contact with the lime plaster of fresco paintings.[8]

Synthetic applications

Synthetic ultramarine, being very cheap, is used for wall painting, the printing of paper hangings, and calico. It also is used as a corrective for the yellowish tinge often present in things meant to be white, such as linen and paper. Bluing or "laundry blue" is a suspension of synthetic ultramarine, or the chemically different Prussian blue, that is used for this purpose when washing white clothes. It is often found in makeup such as mascaras or eye shadows.[19]

Large quantities are used in the manufacture of paper, and especially for producing a kind of pale blue writing paper which was popular in Britain.[19] During World War I, the RAF painted the outer roundels with a color made from ultramarine blue. This became BS 108(381C) aircraft blue. It was replaced in the 1960s by a new color made on phthalocyanine blue, called BS110(381C) roundel blue.[38]

Terminology

Ultramarine is a blue made from natural lapis lazuli, or its synthetic equivalent which is sometimes called "French Ultramarine".[39] More generally "ultramarine blue" can refer to a vivid blue.

The term ultramarine can also refer to other pigments. Variants of the pigment such as "ultramarine red," "ultramarine green," and "ultramarine violet" all resemble ultramarine with respect to their chemistry and crystal structure.[40]

The term "ultramarine green" indicates a dark green while barium chromate is sometimes referred to as "ultramarine yellow".[39] Ultramarine pigment has also been termed "Gmelin's Blue," "Guimet's Blue," "New blue," "Oriental Blue," and "Permanent Blue".[41]

See also

- Blue pigments

- RAL 5002 Ultramarine blue

- International Klein Blue – Deep blue pigment first mixed by the French artist Yves Klein

- List of inorganic pigments

Notes

- "Ultramarine / #120a8f hex color". ColorHexa. Retrieved 2021-12-03.

- Webster's New World Dictionary of American English, Third College Edition 1988.

- Roy, Ashok. "Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics" (PDF). National Gallery of Art. 2: 39.

- Plesters, Joy. "Ultramarine Blue, Natural and Artificial" (PDF). International Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works. 11: 64.

- "ultramarine". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 2011-06-30.

- "History of Ultramarine". www.york.ac.uk. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- "Pigments through the Ages - History - Ultramarine". www.webexhibits.org. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- Roy, Ashok. "Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics" (PDF). National Gallery of Art. 2: 44–45.

- "The Color of Art Pigment Database: Pigment Blue - PB". Art is Creation. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Plesters, Joyce (1966). "Ultramarine Blue, Natural and Artificial". Studies in Conservation. 11 (2): 62–91. doi:10.2307/1505446. JSTOR 1505446.

- Buxbaum, Gunter; Printzen, Helmut; Mansmann, Manfred; Räde, Dieter; Trenczek, Gerhard; Wilhelm, Volker; Schwarz, Stefanie; Wienand, Henning; Adel (2009). "Pigments, Inorganic, 3. Colored Pigments". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/14356007.n20_n02.

- Roy, Ashok. "Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics" (PDF). National Gallery of Art. 2: 38.

- Boer, J. R. J. Van Asperen De (1974). "An Examination of Particle Size Distributions of Azurite and Natural Ultramarine in Some Early Netherlandish Paintings". Studies in Conservation. 19 (4): 233–243. doi:10.2307/1505730. ISSN 0039-3630.

- The color displayed in the color box above matches the color called ultramarine in the 1930 book by Maerz and Paul A Dictionary of Color New York:1930 McGraw-Hill; the color ultramarine is displayed on page 105, Plate 41, Color Sample F12 and is shown as the color lying exactly halfway between blue and violet.

- "All You Need to Know About the International Klein Blue | Widewalls". www.widewalls.ch. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- Maerz and Paul A Dictionary of Color New York:1930--McGraw Hill Color Sample of Ultramarine: Page 105 Plate 41 Color Sample F12 Ultramarine is shown as being one of the colors on the bottom of the plate representing the most highly saturated colors between blue and violet (the colors on the right of the plate represent the most highly saturated colors between violet and rose); ultramarine is shown as being situated at a position exactly one-half of the way between blue and violet.

- Lara Broecke, Cennino Cennini's Il Libro dell'Arte: a New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription, Archetype 2015, pp. 89-90.

- Plesters, Joyce (1966). "Ultramarine Blue, Natural and Artificial". Studies in Conservation. 11 (2): 62–91. doi:10.2307/1505446. ISSN 0039-3630.

- One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ultramarine". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- "Manufacture of ultramarine" (PDF). www.freepatentsonline.com.

- "Ultramarine-Blue-Pigment - Analysis, Applications, Process, Patent, Consultants, Company Profiles, Suppliers, Market, Report". www.primaryinfo.com. Retrieved 2018-10-11.

- Patterson, Steven. "The History of Blue Pigments in the Fine Arts: Painting, From the Perspective of a Paint Maker" (PDF). Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 153: 173.

- Maerz and Paul A Dictionary of Color New York:1930--McGraw Hill Page 206

- Patterson, Steven. "The History of Blue Pigments in the Fine Arts: Painting, From the Perspective of a Paint Maker" (PDF). Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales. 153: 167.

- Roy, Ashok. "Artists' Pigments: A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics" (PDF). National Gallery of Art. 2: 40.

- Hoeniger, Cathleen (1991-01-01). "The Identification of Blue Pigments in Early Sienese Paintings by Color Infrared Photography". Journal of the American Institute for Conservation. 30 (2): 115–124. doi:10.1179/019713691806066782. ISSN 0197-1360.

- Lara Broecke, Cennino Cennini's Il Libro dell'Arte, a New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription, Archetype 2015, p. 89.

- "Palette grinding and_materials". www.essentialvermeer.com. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- "The blue color". artelisaart.blogspot.se. 2012-03-28. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- "assoferrato-the-virgin-in-prayer". www.nationalgallery.org.uk. Retrieved December 6, 2014.

- Description of the painting at www.girl-with-a-pear-earring.info/pallette.htm

- "National Gallery of London discussion of Vermeer's palette". Retrieved Dec 13, 2022.

- "National Gallery essay on the altered appearance of ultramarine in the paintings of Vermeer". Retrieved Dec 13, 2022.

- Goethe, Wolfgang (1914). Italiensche Reise [Italian Journey] (in German). Leipzig, Germany: Insel Verlag. p. 265. From p. 265: "Doch wissen sie, außer diesen beiden, … andern kirchlichen Verzierungen mit Glück angewendet." (Yet they [viz, the stone cutters of Palermo] know, besides these two [types of stone], still more about a material, a product of the fire of their lime kilns. In these is found, after roasting [the lime], a type of glassy flux, which passes from the brightest blue color to the darkest, even to the blackest. These lumps, like other rocks, are cut into thin slabs, appraised according to the level of their color and purity, and, with luck, used instead of lapis lazuli in the inlaying of altars, tombs, and other church decorations.)

- Elsner, L. (1841). "Chemische Untersuchung über die blaue Färbung des Ultramarins" [Chemical investigation of the blue color of ultramarine]. Journal für Praktische Chemie (in German). 24: 385–397. doi:10.1002/prac.18410240157. From pp. 385–386: "Allein es scheint weniger bekannt zu sein, … von Altären u.s.w. gebraucht würde." (Yet it seems to be less well known that von Göthe in the year 1787 during his stay in Palermo (see his Italian Journey) cited a similar observation, as he recounted that in the Sicilian lime ovens, a product of fire, a sort of glassy flux, is found, [which is] of a light blue to dark blue color, [and] which was used as lapis lazuli by local artisans during the inlaying of altars, etc.)

- Tessaërt gave a sample of the pigment to the French chemist Louis Nicolas Vauquelin for analysis: Vauquelin (1814). "Note sur une couleur bleue artificielle analogue à l'outremer" [Note on an artificial blue color similar to ultramarine]. Annales de Chimie et de Physique (in French). 89: 88–91.

- See:

- Gmelin, C.G. (1828). "Ueber die künstliche Darstellung einer dem Ultramarin ähnlichen Farbe" [On the artificial preparation of a pigment similar to ultramarine]. Naturwissenschaftliche Abhandlungen. Herausgeben von Einer Gesellschaft in Würtemberg (Scientific Essays. Published by a Society in Würtemberg) (in German). 2 (10): 191–224. Bibcode:1828AnP....90..363.. doi:10.1002/andp.18280901022.

- Gmelin, C.G. (1828). "Ueber die künstliche Darstellung einer dem Ultramarin ähnlichen Farbe" [On the artificial preparation of a pigment similar to ultramarine]. Annalen der Physik und Chemie. 2nd series (in German). 14 (10): 363–371. Bibcode:1828AnP....90..363.. doi:10.1002/andp.18280901022.

- Watts, Henry (1869). "Ultramarine". A Dictionary of Chemistry and the Allied Branches of Other Sciences. Vol. 5. London, England: Longmans, Green, and Co. p. 937.

- "Ultramarine blue 464# (P.B29)_MEI DAN PIGMENT". m.mdpigment.com. Retrieved 2023-04-12.

- Paterson, Ian (2003), A dictionary of colour, pp. 35, 169, 228, 396

- Eastaugh, Nicholas; Walsh, Valentine; Chaplin, Tracey; Siddall, Ruth (2008), Pigment Compendium – A Dictionary and Optical Microscopy of Historical Pigments, pp. 585–587, ISBN 978-0-7506-8980-9

- Kelly, Kenneth Low; Judd, Deane Brewster (1976), Color: Universal Language and Dictionary of Names, U.S. Department of Commerce, National Bureau of Standards, p. 150

Further reading

- Bomford, David (2000). A Closer Look – Colour. National Gallery Company Limited. ISBN 978-1-85709-442-8.

- Broecke, Lara (2015). Cennino Cennini's Il Libro dell'Arte: a New English Translation and Commentary with Italian Transcription. Archetype. ISBN 978-1-909492-28-8.

- Mangla, Ravi (8 June 2015), "True blue: a brief history of ultramarine", Paris Review—Daily.

- Plesters, J. (1993), "Ultramarine Blue, Natural and Artificial", in Artists’ Pigments. A Handbook of Their History and Characteristics, Vol. 2: A. Roy (Ed.) Oxford University Press, p. 37-66

References

External links

![]() Media related to Ultramarine at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ultramarine at Wikimedia Commons

- Discussion of ultramarine in an article on blue pigments in early Sienese paintings from The Journal of the American Institute for Conservation

- National Gallery essay on the altered appearance of ultramarine in the paintings of Vermeer

- Ultramarine natural, ColourLex

- Ultramarine artificial, ColourLex

- Shades and tints and color harmonies of ultramarine, HTMLCSScolor.com

- More shades and tints and color harmonies of ultramarine, HTMLCSScolor.com

- An alternative ultramarine color (#5A7CC2) from Pantone, pantone.com