Chilean peso

The peso is the currency of Chile. The current peso has circulated since 1975, with a previous version circulating between 1817 and 1960. Its symbol is defined as a letter S with either one or two vertical bars superimposed prefixing the amount,[1] $ or ![]() ; the single-bar symbol, available in most modern text systems, is almost always used. Both of these symbols are used by many currencies, most notably the United States dollar, and may be ambiguous without clarification, such as CLP$ or US$. The ISO 4217 code for the present peso is CLP. It was divided into 100 centavos until 31 May 1996, when the subdivision was formally eliminated (requiring payments to be made in whole pesos). In February 2023, the exchange rate was around CLP$800 to US$1.[2]

; the single-bar symbol, available in most modern text systems, is almost always used. Both of these symbols are used by many currencies, most notably the United States dollar, and may be ambiguous without clarification, such as CLP$ or US$. The ISO 4217 code for the present peso is CLP. It was divided into 100 centavos until 31 May 1996, when the subdivision was formally eliminated (requiring payments to be made in whole pesos). In February 2023, the exchange rate was around CLP$800 to US$1.[2]

| Peso chileno (Spanish) | |

|---|---|

| ISO 4217 | |

| Code | CLP (numeric: 152) |

| Unit | |

| Symbol | |

| Denominations | |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | 1000, 2000, 5000, 10,000, 20,000 pesos |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 10, 50, 100, 500 pesos |

| Demographics | |

| User(s) | Chile |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Banco Central de Chile |

| Website | www |

| Mint | Casa de Moneda |

| Website | www |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 6.5% |

| Source | 2023 () |

First peso, 1817–1960

The first Chilean peso was introduced in 1817, at a value of 8 Spanish colonial reales. Until 1851, the peso was subdivided into 8 reales, with the escudo worth 2 pesos. In 1835, copper coins denominated in centavos were introduced, but it was not until 1851 that the real and escudo denominations ceased to be issued and further issues in centavos and décimos (worth 10 centavos) commenced. Also in 1851, the peso was set equal 5 French francs on the sild, 22.5 grams pure silver. However, gold coins were issued to a different standard to that of France, with 1 peso = 1.37 grams gold (5 francs equalled 1.45 grams gold). In 1885, a gold standard was adopted, pegging the peso to the British pound sterling at a rate of 13+1⁄3 pesos = 1 pound (1 peso = 1 shilling 6 pence). This was reduced in 1926 to 40 pesos = 1 pound (1 peso = 6 pence). From 1925, coins and banknotes were issued denominated in cóndores, worth 10 pesos. The gold standard was suspended in 1932 and the peso's value fell further. The escudo replaced the peso on 1 January 1960 at a rate 1 escudo = 1000 pesos.

Coins

Between 1817 and 1851, silver coins were issued in denominations of 1⁄4, 1⁄2, 1, and 2 reales and 1 peso (also denominated 8 reales), with gold coins for 1, 2, 4, and 8 escudos. In 1835, copper 1⁄2 and 1 centavo coins were issued. A full decimal coinage was introduced between 1851 and 1853, consisting of copper 1⁄2 and 1 centavo, silver 1⁄2 and 1 décimo (5 and 10 centavos), 20 and 50 centavos, and 1 peso, and gold 5 and 10 pesos. In 1860, gold 1 peso coins were introduced, followed by cupronickel 1⁄2, 1 and 2 centavos between 1870 and 1871. Copper coins for these denominations were reintroduced between 1878 and 1883, with copper 2+1⁄2 centavos added in 1886. A new gold coinage was introduced in 1895, reflecting the lower gold standard, with coins for 2, 5, 10 and 20 pesos. In 1896, the 1⁄2 and 1 décimo were replaced by 5 and 10 centavo coins.

In 1907, a short-lived, silver 40 centavo coin was introduced following cessation of production of the 50 centavo coin. In 1919, the last of the copper coins (1 and 2 centavos) were issued. The following year, cupronickel replaced silver in the 5, 10 and 20 centavo coins. A final gold coinage was introduced in 1926, in denominations of 20, 50 and 100 pesos. In 1927, silver 2 and 5 peso coins were issued. Cupronickel 1 peso coins were introduced in 1933, replacing the last of the silver coins. In 1942, copper 20 and 50 centavos and 1 peso coins were introduced. The last coins of the first peso were issued between 1954 and 1959. These were aluminum 1, 5 and 10 pesos.

Gold bullion coins with nominals in 100 pesos were minted between 1932 and 1980 (i.e. they survived into the periods of two later currencies).[3] In addition, there was a special issue of gold coins (100, 200 and 500 pesos) in 1968.

Coins issued in values of 5 and 10 pesos from 1956 onwards, as well as bullion coins of 20, 50 and 100 pesos issued from 1925 to 1980 (exceeding the validity of this monetary standard by 20 years) also bring such equivalence in condors, being 10 pesos per condor.

Banknotes

The first Chilean paper money was issued between 1840 and 1844 by the treasury of the Province of Valdivia, in denominations of 4 and 8 reales. In the 1870s, a number of private banks began issuing paper money, including the Banco Agrícola, the Banco de la Alianza, the Banco de Concepción, the Banco Consolidado de Chile, the Banco de A. Edwards y Cía., the Banco de Escobar, Ossa y Cía., the Banco Mobiliario, the Banco Nacional de Chile, the Banco del Pobre, the Banco Sud Americano, the Banco del Sur, the Banco de la Unión, and the Banco de Valparaíso. Others followed in the 1880s and 1890s. Denominations included 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 500 pesos. One bank, the Banco de A. Edwards y Cía., also issued notes denominated in pounds sterling (libra esterlina).

In 1881, the government issued paper money convertible into silver or gold, in denominations of 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, and 1000 pesos. 50 centavo notes were added in 1891 and 500 pesos in 1912. In 1898, provisional issues were made by the government, consisting of private bank notes overprinted with the words "Emisión Fiscal". This marked the end of the production of private paper money.

In 1925, the Banco Central de Chile began issuing notes. The first, in denominations of 5, 10, 50, 100, and 1000 pesos, were overprints on government notes. In 1927, notes marked as "Billete Provisional" were issued in denominations of 5, 10, 50, 100, 500, and 1000 pesos. Regular were introduced between 1931 and 1933, in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000, and 10,000 pesos. The 1 and 20 peso notes stopped production in 1943 and 1947, respectively. The remaining denominations continued production until 1959, with a 50,000-peso note added in 1958.

Notes issued after 1925 show the equivalence in condors, which was at the rate of 10 pesos per condor.

Second peso, 1975–present

The current peso was introduced on 29 September 1975 by decree 1,123, replacing the escudo at a rate of 1 peso for 1,000 escudos. This peso was subdivided into 100 centavos until 1984.

Coins

In 1975, coins were introduced in denominations of 1, 5, 10, and 50 centavos and 1 peso. The 1, 5, and 10 centavo coins were very similar to the 10, 50, and 100 escudo coins they replaced. Since 1983, inflation has left the centavo coins obsolete. 5 and 10 peso coins were introduced in 1976, followed by 50 and 100 peso coins in 1981 and by a bi-metallic 500 peso coin in 2000. Coins currently in circulation are in denominations of 1, 5, 10, 50, 100, and 500 pesos; however, as of 2016 the value of the peso has depreciated enough that most retailers and others tend to use prices that are multiples of 10 pesos, ignoring smaller amounts. The 1 peso coin is rare. On 26 October 2017 the Mint stopped producing 1 and 5 peso coins, and started accepting those coins directly at the mint to exchange for larger denomination. On 1 November 2017 commercial entities began rounding off amounts for payment in cash, rounding down for amounts ending in 1 through 5 pesos, rounding up for amounts ending in 6 through 9 pesos. Electronic transactions and cheques are not affected. This change has affected various charities which had programs to accept donations at the cash register.[4]

Right after the military dictatorship in Chile (1973–1990) ended, the obverse designs of the 5 and 10 peso coins were changed. Those coins had borne the image of a winged female figure wearing a classical robe and portrayed as if she had just broken a chain binding her two hands together (a length of chain could be seen hanging from each of her wrists); beside her appear the date of the coup d'état Roman numerals and the word LIBERTAD (Spanish for "liberty"). After the return of democracy, a design with the portrait of Bernardo O'Higgins was adopted.

In 2001, a newly redesigned 100-peso coin bearing the image of a Mapuche woman began to circulate. In February, 2010, it was discovered that on the 2008 series of the 50 peso coins the country name CHILE had been misspelled as CHIIE. The national mint said that it did not plan to recall the coins. Worth about US$0.09 each at the time, the faulty coins became collectors' items.[5]

Banknotes

In 1976, banknotes were introduced in denominations of 5, 10, 50, and 100 pesos with the reverses of the two lowest denominations resembling those of the 5000- and 10,000-escudo notes they replaced. Inflation has since led to the issue of much higher denominations. Five-hundred-peso notes were introduced in May, 1977, followed by the 1000-peso (in June, 1978), 5000-peso (June, 1981), 10,000-peso (June, 1989), 2000-peso (December, 1997), and 20,000-peso (December, 1998) notes. The 5, 10, 50, 100, and 500-peso banknotes have been replaced by coins, leaving only the 1000, 2000, 5000, 10,000, and 20,000 peso notes in circulation. Redesigned versions of the four highest denominations were issued in 2009 and 2010. The popular new 1000-peso banknote was issued on 11 May 2011.[6]

Since September 2004, the 2000-peso note has been issued only as a polymer banknote; the 5000-peso note began emission in polymer in September 2009; and the 1000-peso note was switched to polymer in May, 2011. This was the first time in Chilean history that a new family of banknotes was put into circulation for other cause than the effects of inflation. As of January 2012, only the 10,000 and 20,000 peso notes are still printed on cotton paper. All new notes have the same 70 mm (2.8 in) height, while their length varies in 7 mm (0.28 in) steps according to their face values: the shortest is the 1000-peso note and the longest is the 20,000-pesos.[7] The new notes are substantially more difficult to falsify because of new security measures.

The design and production of the whole new family of banknotes was assigned to the Australian company Note Printing Australia Ltd for the 1000, 2000 and 5000 peso notes, and the Swedish company Crane AB for the 10,000 and 20,000 peso notes[6]

In popular culture

Colloquial Chilean Spanish has informal names for some banknotes and coins. These include luca for a thousand pesos, quina for five hundred pesos (quinientos is Spanish for "five hundred"), and gamba ("prawn") for one hundred pesos (or more recently 100,000 pesos). These names are old: For example, gamba and luca applied to 100 and 1000 escudos before 1975. The term gamba is a reference to the color of one hundred pesos banknote issued between 1933 and 1959.

Depending on context, a gamba might mean one hundred pesos or one hundred thousand pesos. For instance a new computer might be said to cost two gambas. This means two hundred thousand pesos. Less commonly, this applies to luca, taken to mean one million, usually referred to as palo.

The cover of the 2007 Velvet Revolver album Libertad features a stylized version of the angel from the Pinochet-era 10 pesos coin. Guitarist Slash, who personally chose the image, claimed he had no idea of the dark significance of it at the time.

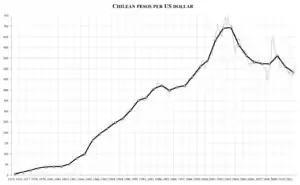

Value of the peso against the United States dollar

Average value of US$1[8] Date Chilean pesos August 2023 856.81 July 2023 814.26 June 2023 798.20 May 2023 797.52 April 2023 804.72 March 2023 809.16 February 2023 800.06 January 2023 825.03 February 2021 722.80 January 2021 722.71 December 2020 734.73 November 2020 762.88 October 2020 788.27 September 2020 773.40 August 2020 784.66 July 2020 784.73 June 2020 793.72 May 2020 821.81 April 2020 853.38 March 2020 839.38 February 2020 796.38 January 2020 772.65 12-month average 792.22 2019 702.63 2018 640.29 2017 649.33 2016 676.83 2015 654.25 2010 510.38 2005 559.86 2000 538.87 1995 396.78 1990 304.68 1985 160.73

Between 1974 and 1979, the Chilean peso was allowed to float within a crawling band.[9] From June 1979 to 1982 the peso was pegged to the United States dollar at a fixed exchange rate.[10] In June 1982, during that year's economic crisis, the peso was devalued and different exchange rate regimes were used.[9][11] In August 1984 the peso returned to a system of crawling bands, which were periodically adjusted to reflect differences between external and internal inflation.[11]

Starting in September 1999, the Chilean peso was allowed to float freely against the United States dollar for the first time. Chile's Central Bank, however, reserved the right to intervene, which it did on two occasions to counter excessive depreciation: the first, in August and September 2001, coincided with Argentina's convertibility crisis and with the September 11 attacks in the United States. The second, in October 2002, was during Brazil's presidential election.[12]

During the first months of the Presidency of Gabriel Boric, the US dollar began to have a strong appreciation against the Chilean peso, among the reasons was the very strong drop in the raw material of Copper, in addition to political and economic instability due to the rise of the cost of living reaching its highest level in 20 years of 2-digit inflation of 14.1%, also due to uncertainty about the arrival of the 2022 Chilean Constitutional Plebiscite that would take place a few months later between approval and rejection and the discouraging economic figures in China led the dollar to exceed the figure of 1000 Pesos for the first time in its history, reaching a price of more than 1050 Pesos per dollar; After that, the Central Bank of Chile carried out its largest exchange intervention in the market, intervening on Thursday, July 14, 2022 for an amount of up to US$25,000 million starting on Monday, July 18, 2022 and until September 30. of 2022. [13]

During 2023, the dollar has had a strong devaluation that was quoted at approximately 780 Pesos per dollar. On Friday, July 28, 2023, the Central Bank of Chile announced the strongest drop since 2009 in the monetary policy rate with a drop substantial 100 basic points from 11.25% to 10.25%, which led the dollar to have a strong rise as there began to be greater access to loans and as time deposits were not profitable, they led to reaching 860 pesos per dollar. [14]

| Current CLP exchange rates | |

|---|---|

| From Google Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR BRL ARS |

| From Yahoo! Finance: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR BRL ARS |

| From XE.com: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR BRL ARS |

| From OANDA: | AUD CAD CHF CNY EUR GBP HKD JPY USD INR BRL ARS |

See also

- Economy of Chile

- Unidad de Fomento — inflation indexing of the Peso used in many contracts in Chile

Notes

- "Ley Chile Móvil". Leychile.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved 23 December 2015. "Su símbolo será la letra S sobrepuesta con una o dos líneas verticales y se antepondrá a su expresión numérica."

- Quote from IDC on TradingView, 13 February 2023.

- "100 Pesos, Chile". en.numista.com. Retrieved 1 March 2022.

- "Instituciones sufren fuerte baja en donaciones del vuelto tras aplicación de ley de redondeo". ADN Radio (adnradio.cl). 29 January 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- "Chilean mint spells country's name wrong on coins". The Daily Telegraph (telegraph.co.uk). 12 February 2010. Retrieved 15 June 2015.

- "Banco Central lanzó nuevo billete de $1.000 y anunció que entrará en circulación el 11 de mayo". La Tercera. 16 March 2011. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- "Nuevos Billetes". Nuevosbilletes.cl. Archived from the original on 20 June 2012. Retrieved 1 June 2012.

- "Monthly Average Chilean Peso per 1 US Dollar Monthly average". X-Rates. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- Roberto Toso C. (April 1983). "El tipo de cambio fijo en Chile: la experiencia en el período 1979–1982" (PDF). Serie de Estudios Económicos (in Spanish). Central Bank of Chile. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 June 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- José de Gregorio R.; Andrea Tokman R.; Rodrigo Valdés (August 2005). "Tipo de Cambio Flexible con Metas de Inflación en Chile: Experiencia y Temas de Interés" (PDF). Documentos de Política Económica Nº 14 – Agosto 2005 (in Spanish). Central Bank of Chile. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- Felipe Morandé L.; Matías Tapia G. (December 2002). "Política cambiaria en Chile: El abandono de la banda y la experiencia de flotación" (PDF). Economía Chilena Volumen 5 – Nº 3 / diciembre 2002 (in Spanish). Central Bank of Chile. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- José de Gregorio R.; Andrea Tokman R. (December 2005). "El 'miedo a flotar' y la política cambiaria en Chile" (PDF). Economía Chilena Volumen 8 – Nº 3 / diciembre 2005 (in Spanish). Central Bank of Chile. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 May 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2012.

- "Consejo del Banco Central de Chile anuncia programa de intervención cambiaria y provisión preventiva de liquidez en dólares - Banco Central de Chile". www.bcentral.cl (in European Spanish). Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- Financiero, Diario; Vergara, S. Valdenegro y C. "Comienza el nuevo ciclo: Banco Central sorprende con una baja de la tasa de interés de 100 puntos, la mayor desde 2009 | Diario Financiero". www.df.cl (in Spanish). Retrieved 31 August 2023.

References

- Krause, Chester L.; Clifford Mishler (1991). Standard Catalog of World Coins: 1801–1991 (18th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0873411501.

- Pick, Albert (1994). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: General Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (7th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-207-9.

- Pick, Albert (1990). Standard Catalog of World Paper Money: Specialized Issues. Colin R. Bruce II and Neil Shafer (editors) (6th ed.). Krause Publications. ISBN 0-87341-149-8.

External links

| Preceded by: Spanish colonial real Ratio: 8 reales = 1 peso |

Currency of Chile 1817 – 31 December 1959 |

Succeeded by: Chilean escudo Ratio: 1 escudo = 1000 pesos |

| Preceded by: Chilean escudo Ratio: 1 peso = 1000 escudos |

Currency of Chile 1975 – |

Succeeded by: Current |

.svg.png.webp)