Joe Cino

Joseph Cino (November 16, 1931 – April 2, 1967), was an Italian-American theatre producer. The Off-Off-Broadway theatre movement is generally credited to have begun at Cino's Caffe Cino in the West Village of Manhattan.

Caffe Cino and off-off-Broadway

Founding the Caffe Cino

Joe Cino moved from Buffalo to New York City to become a dancer. In 1958, Cino retired from dancing and rented a storefront at 31 Cornelia Street in Greenwich Village to open a coffeehouse where his friends could socialize. He and his early customers created their own patois of Italian and English. He did not intend Caffe Cino to become a theatre, and instead visualized a café where he could host folk music concerts, poetry readings, and art exhibits. Actor and theatre director Bill Mitchell says he suggested that Cino start producing plays at the Cino. Dated photographs show that plays were staged at the coffeehouse from at least December 1958. After 1960, plays were usually directed by Bob Dahdah. Cino initially saw theatre as simply another kind of event to host.

Off-Off-Broadway

Compared to painting and writing, theatre is an expensive art form that requires a space and collaborators, and is subject to the scrutiny of church, state, and the press. The Caffe Cino made its living not from public approval of the work it presented, but from selling food and drink. No one was paid, except the police who were paid off, reviewers seldom came (and reviews were usually published after a show had closed), and theatre entered the modern era, which the other art forms had entered a hundred years earlier. Dozens of theaters based on the Cino model began to appear in places making their living other ways: cafes, bars, art galleries, and churches. To distinguish these theaters from Broadway (large Actors' Equity theatres) and Off-Broadway (smaller Equity theatres), this new theatre world became known as Off-Off-Broadway. For the first time in history, the stage could be unpopular, an area of primary expression, rebellion, novelty, and a vehicle for social and aesthetic change. One novelist wrote: "Off-Off-Broadway: The first place in human history where theatre is treated as the equal of the other arts, as a thing responsible and important above popularity ratings, outside monetary concerns, beyond academic and legal restrictions: The first studio of theater where playwrights can experiment as painters and poets have done for a century, free from the tyranny of audience, box-office, church, and criticism."

Caffe Cino's first productions were plays from established playwrights such as Tennessee Williams and Jean Giraudoux. The first original play Cino produced is thought to be James Howard's Flyspray, in the summer of 1960. Cino became so excited by the audience response and his own response to the plays that he quickly established a weekly schedule for theatrical performances. He introduced the acts by saying, "It's magic time!"[1]

The first productions at Caffe Cino were done on the café floor. Eventually, Cino constructed a makeshift 8' x 8' stage from milk cartons and carpet remnants to use for some productions. The limited space dictated a need for small casts and minimal sets, usually built from scraps Cino found in the streets. Cino relied heavily on lighting designer Johnny Dodd, who lit the stage using electricity stolen from the city grid by Cino's lover, electrician Jonathan "Jon" Torrey (died January 5, 1967). The space created intimacy between the performers and audience, with little room for typical fourth-wall illusionary theatre. Cino decorated the café with fairy lights, mobiles, glitter, and Chinese lanterns, and covered the walls with memorabilia and personal effects.

Selection of plays

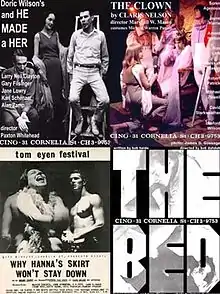

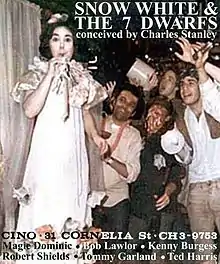

Cino seldom read the plays submitted for his consideration. He was more likely to ask a novice playwright what his astrological sign was. If he liked the answer, he staged the play. Many of the young playwrights who premiered their works at Cino's venue, including Doric Wilson (who would later found TOSOS, the first professional gay theatre), William M. Hoffman (who later wrote As Is), Robert Patrick (Kennedy's Children), John Guare (Six Degrees of Separation), Tom Eyen (Dreamgirls), Sam Shepard (True West), Robert Heide (The Bed, filmed by Andy Warhol), Paul Foster (Tom Paine), Jean-Claude van Itallie (America Hurrah), and Lanford Wilson (Burn This); directors Tom O'Horgan (Hair) and Marshall W. Mason (Talley's Folly); and actors such as Al Pacino and Bernadette Peters went on to significant commercial and critical success. Wilson's four hits in 1961 made him off-off-Broadway's first cult success and proved that there was an audience for new, daring plays. Foster's Beckettian puppet play, Balls, was so popular that one of the first articles about off-off-Broadway was titled, "Have You Caught 'Balls?'" Wilson's The Madness of Lady Bright (May 1964), about a lonely, aging drag queen, was the Cino's breakthrough hit. The play was performed over 200 times, with Neil Flanagan in the title role. Although playwrights Jerry Caruana, Wilson, Claris Nelson, and David Starkweather had each previously presented numerous well-received works at the Caffe Cino, it was the success of The Madness of Lady Bright which convinced Cino to concentrate on works by new playwrights.

Beginnings of gay theatre

Caffe Cino was a friendly social center for gay men at a time when most gay life was restricted to bars and bathhouses. Although The Madness of Lady Bright is often referred to as the first American play to feature an explicitly gay character, a number of earlier Cino productions also dealt with gay identity, including Wilson's 1961 Now She Dances! Alan Lysander James presented several programs of Oscar Wilde material at the Cino from 1962 through 1965, while director Andy Milligan staged a number of homoerotic productions, including Jean Genet's The Maids and Deathwatch and a dramatization of Tennessee Williams' short story One Arm, which was the first production at La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club. After The Madness of Lady Bright, however, the Cino came to be recognized as a venue for plays dealing with explicitly gay themes. Robert Patrick's The Haunted Host, William M. Hoffman's Good Night, I Love You, Bob Heide's The Bed, and Haal Borske's The Brown Crown all dealt with gay themes. Ruth Landshoff York, H.M. Koutoukas, Jean-Claude van Itallie, Jeffrey Weiss, Soren Agenoux, and George Birimisa presented plays with gay content at Cino, which would likely have been unacceptable outside of off-off-Broadway at that time.

Conflict between experimental and commercial theatre

The musical Dames at Sea opened at the Cino in May 1966 for an unprecedented twelve-week run. That production, along with other long runs and revivals of past hits (especially those by Wilson, Eyen, and Heide) and the availability of better facilities in some of the new off-off-Broadway theaters, drove some playwrights away from the Cino. Some regulars, accustomed to avant-garde works such as those of Koutoukas, disliked the commercial Dames at Sea, while the new, mainstream audience attracted by Dames at Sea and Wilson's plays didn't like experimental works, such as a series of plays using comic books as scripts (first conceived by Donald L. Brooks).

Police raids

Throughout Caffe Cino's existence, Joe Cino experienced police raids as he took responsibility for licensing violations. There was no applicable license available for the Caffe Cino. Flyers were designed by artist Kenny Burgess so that they looked like abstract art to passersby but could still be read by patrons. Police were aware of the Caffe Cino's productions, and Joe Cino paid off the police a significant amount of money during the 1960s. Rumors abounded that Cino received protection from the Mafia due to his alleged family affiliations. These rumors have never been proven. Cino was industrious, acting as host while simultaneously serving as maintenance man, server, and barista. He generally kept other jobs in order to support himself and the café. He lived by the motto "Do what you have to do" and encouraged his writers to do the same. At the Caffe Cino's peak, plays were performed twice nightly, with three shows per night on weekends. The goal was not simply to get as many paying customers as possible. Even if there was no audience, Cino insisted on a show. He would tell the performers to, "Do it for the room," and they did. After Cino's death, police issued summonses so frequently that when a policeman appeared on the block, actors were ready at a signal from the doorman to leap offstage and sit, often in fantastic costumes, at tables with patrons.

Publicity and reputation

Caffe Cino shows received little major press, a notable exception being the trade paper Show Business, where married critics Joyce and Gordon Tretick risked their jobs by promoting the Caffe Cino and other off-off-Broadway venues. Downtown, critic and playwright Michael Smith and other Village Voice writers were supportive. They awarded a shared Obie to Joe Cino and Ellen Stewart, founder of La Mama Experimental Theatre Club, in 1965. A number of short-lived downtown publications intermittently covered single shows. Most mainstream mentions were condescending, such as a famous 1965 New York Times Magazine article which basically seemed to be shocked by the poverty of the movement (the article was entitled "The Pass the Hat Theatre Circuit"). Playwright and actor Ruth Landshoff York persuaded Glamour magazine to publish an article on a group of playwrights. Life magazine took photographs around off-off-Broadway for weeks for a feature that was never published. Generally, the minimal international press that the movement got was more enthusiastic. The mainstream attitude is summarized in this anecdote: George Haimsohn, librettist and lyricist for Dames at Sea and Psychedelic Follies, said the reason the Caffe Cino was omitted from publicity when the musical moved was because, "We don't want to be associated with drugs and homosexuality." The Cino's reputation was improved in the late 1970s, when Ellen Stewart proclaimed, "It was Joseph Cino who started Off-Off Broadway." Leah D. Frank, founding editor of the first enduring Off-Off-Broadway publication, Other Stages, commissioned Cino artists to write about their experiences there. In recent years, several books about early Off-Off-Broadway and two specifically about the Caffe Cino have been published.

Posthumous recognition

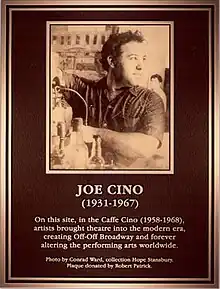

In 1985, scholar Richard Buck and Cino artist Magie Dominic curated an exhibition at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts of images and artifacts demonstrating the Caffe Cino's importance in theatre history. In 2005, in honor of Joe Cino's courage and innovation, the New York Innovative Theatre Awards presented the first Caffe Cino Fellowship Award. This award is given annually to an extraordinary Off-Off-Broadway theatre company. In 2007, it was awarded to the first "playwright-in-residence" at the Caffe, Doric Wilson. On April 28, 2008, the office of the President of the Borough of Manhattan issued a proclamation honoring Joe Cino's achievement in founding Off-Off Broadway which "altered the world's conception of drama's possibilities forever."[2] The proclamation was read by John Guare at the unveiling of a bronze plaque depicting Cino at his espresso machine affixed to the wall at 31 Cornelia Street.

Personal life

Joe Cino, the son of first-generation Sicilian-Americans, was born into a working class family in Buffalo, New York. He moved to New York City at the age of sixteen, studying performing arts for two years in hopes of becoming a dancer. Though he made his living dancing throughout much of the 1950s, his continual struggles with weight curtailed his dance career.

Cino became addicted to amphetamines as he struggled to keep up the pace that Caffe Cino demanded. On January 5, 1967, Cino's partner Jon Torrey was electrocuted and died in Jaffrey, New Hampshire. Though his death was ruled accidental, insiders claimed that he committed suicide. The event sent Cino into a depressive spiral. He began socializing with members from Andy Warhol's Factory who'd been attracted to the Caffe Cino by the success of Dames at Sea, including Ondine, with whom Cino did a great deal of drugs. Caffe Cino was beginning to suffer. As a commercial enterprise, it was ineligible for the government grants which allowed other experimental theatres to prosper. Joe refused to charge any admission.

On March 31, 1967, Cino hacked his arms and stomach with a kitchen knife. He was rushed to the hospital, where doctors announced that he would live. However, three days later on April 3, Jon Torrey's birthday, Cino died. He was age 35. Although friends tried to keep Caffe Cino open, it closed the following year in 1968, succumbing to the strict cabaret laws being enforced by the young councilman Ed Koch.

References

- "Caffe Cino - Stone". SIU. Archived from the original on August 5, 2012.

- "Joe Cino Appreciation Day - News from the IT Awards". NYITAwards.com. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

Further reading

- Banes, Sally. Greenwich Village 1963: Avant-Garde Performance and the Effervescent Body. 1993. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999.

- Bottoms, Stephen J. Playing Underground: A Critical History of the 1960s Off-Off-Broadway Movement. 2004. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press, 2007.

- Crespy, David A. Off-Off-Broadway Explosion: How Provocative Playwrights of the 1960s Ignited a New American Theater. New York: Back Stage Books, 2003.

- Dominic, Magie. The Queen of Peace Room. Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Lauer University Press, 2002.

- Gordy, Douglas W. "Joseph Cino and the First Off-Off Broadway Theater." In Passing Performances: Queer Readings of Leading Players in American Theater History, edited by Robert A. Schanke and Kimberly Bell Marra, 303–323. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, 1998.

- McDonough, Jimmy. The Ghastly One: The Sex-Gore Netherworld of Filmmaker Andy Milligan. Chicago: Acappella, 2002.

- Stone, Wendell C. Caffe Cino: The Birthplace of Off-Off-Broadway. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

- Susoyev, Steve & Birimisa, George. Return to the Caffe Cino. San Francisco, CA: Moving Finger Press, 2006.

External links

- Joe Cino's page on La MaMa Archives Digital Collections

- 75 pages of captioned photos from/relating to the Caffe Cino (plus links to other photos and print, audio, and video interviews with Cino people)

- "The Caffe Cino" (2007) video interviews with Cino playwrights on YouTube

- Caffe Cino exhibit at Lincoln Center (1985)

- New York Innovative Theatre Awards

- Doric Wilson on the Caffe Cino

- 1961 recording of Doric Wilson's "And He Made a Her" (introduced by voice of Joe Cino)

- Michael Smith on the Caffe Cino.

- Donald L. Brooks' Cino play

- William M. Hoffman's video interviews with Cino people (interviews #13, 14, 15, 16)

- Richard Bucks' reviews of six off-off-Broadway books

- Robert Patrick's history of the Cino

- James Gossage photographs, 1965–1975 Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Robert Patrick papers, c. 1940–1984 Billy Rose Theatre Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

- Photograph of 22 off-off-Broadway playwrights (1966)

- Photograph of Cino interior in 1961 and photograph of Cino interior in 1967

- Observations on "Warhol People" at the Cino

- Robert Patrick's Village Voice interview about the Caffe Cino (May 2009)

- La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. Clipping: "What's Happening Off Off-Broadway -- Where Nothing is Taboo" (1966). Accessed August 29, 2018.