Petroleum industry in Canada

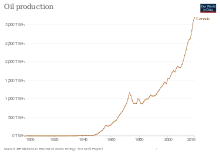

Petroleum production in Canada is a major industry which is important to the economy of North America. Canada has the third largest oil reserves in the world and is the world's fourth largest oil producer and fourth largest oil exporter. In 2019 it produced an average of 750,000 cubic metres per day (4.7 Mbbl/d) of crude oil and equivalent. Of that amount, 64% was upgraded from unconventional oil sands, and the remainder light crude oil, heavy crude oil and natural-gas condensate.[1] Most of the Canadian petroleum production is exported, approximately 600,000 cubic metres per day (3.8 Mbbl/d) in 2019, with 98% of the exports going to the United States.[1] Canada is by far the largest single source of oil imports to the United States, providing 43% of US crude oil imports in 2015.[2]

| This article is part of a series on |

| Petroleum in Canada |

|---|

| Resources and producers |

| Categories |

|

|

Economy of Canada Energy policy of Canada |

The petroleum industry in Canada is also referred to as the "Canadian Oil Patch"; the term refers especially to upstream operations (exploration and production of oil and gas), and to a lesser degree to downstream operations (refining, distribution, and selling of oil and gas products). In 2005, almost 25,000 new oil wells were spudded (drilled) in Canada. Daily, over 100 new wells are spudded in the province of Alberta alone.[3] Although Canada is one of the largest oil producers and exporters in the world, it also imports significant amounts of oil into its eastern provinces since its oil pipelines do not extend all the way across the country and many of its oil refineries cannot handle the types of oil its oil fields produce. In 2017 Canada imported 405,700 bbl/day (barrels per day) and exported 1,115,000 bbl/day of refined petroleum products.[4][5]

History

The Canadian petroleum industry developed in parallel with that of the United States. The first oil well in Canada was dug by hand (rather than drilled) in 1858 by James Miller Williams near his asphalt plant at Oil Springs, Ontario. At a depth of 4.26 metres (14.0 ft)[6] he struck oil, one year before "Colonel" Edwin Drake drilled the first oil well in the United States.[7] Williams later went on to found "The Canadian Oil Company" which qualified as the world’s first integrated oil company.

Petroleum production in Ontario expanded rapidly, and practically every significant producer became his own refiner. By 1864, 20 refineries were operating in Oil Springs and seven in Petrolia, Ontario. However, Ontario's status as an important oil producer did not last long. By 1880 Canada was a net importer of oil from the United States.

Canada's unique geography, geology, resources and patterns of settlement have been key factors in the history of Canada. The development of the petroleum sector helps illustrate how they have helped make the nation quite distinct from the United States. Unlike the United States, which has a number of different major oil producing regions, the vast majority of Canada's petroleum resources are concentrated in the enormous Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), one of the largest petroleum-containing formations in the world. It underlies 1,400,000 square kilometres (540,000 sq mi) of Western Canada including most or part of four western provinces and one northern territory. Consisting of a massive wedge of sedimentary rock up to 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) thick extending from the Rocky Mountains in the west to the Canadian Shield in the east, it is far distant from Canada's east and west coast ports as well as its historical industrial centres. It is also far from American industrial centres. Because of its geographic isolation, the area was settled relatively late in the history of Canada, and its true resource potential was not discovered until after World War II. As a result, Canada built its major manufacturing centres near its historic hydroelectric power sources in Ontario and Quebec, rather than its petroleum resources in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Not knowing about its own potential, Canada began to import the vast majority of its petroleum from other countries as it developed into a modern industrial economy.

The province of Alberta lies at the centre of the WCSB and the formation underlies most of the province. The potential of Alberta as an oil-producing province long went unrecognized because it was geologically quite different from American oil producing regions. The first oil well in western Canada was drilled in southern Alberta in 1902, but did not produce for long and served to mislead geologists about the true nature of Alberta's subsurface geology. The Turner Valley oil field was discovered in 1914, and for a time was the biggest oil field in the British Empire, but again it misled geologists about the nature of Alberta's geology. In Turner Valley, the mistakes oil companies made led to billions of dollars in damage to the oil field by gas flaring which not only burned billions of dollars worth of gas with no immediate market, but destroyed the field's gas drive that enabled the oil to be produced. The gas flares in Turner Valley were visible in the sky from Calgary, 75 km (50 mi) away. As a result of the highly visible wastage, the Alberta government launched vigorous political and legal attacks on the Canadian Government and the oil companies that continued until 1938 when the province set up the Alberta Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board and imposed strict conservation legislation.

The status of Canada as an oil importer from the US suddenly changed in 1947 when the Leduc No. 1 well was drilled a short distance south of Edmonton. Geologists realized that they had completely misunderstood the geology of Alberta, and the highly prolific Leduc oil field, which has since produced over 50,000,000 m3 (310,000,000 bbl) of oil was not a unique formation. There were hundreds more Devonian reef formations like it underneath Alberta, many of them full of oil. There was no surface indication of their presence, so they had to be found using reflection seismology. The main problem for oil companies became how to sell all the oil they had found rather than buying oil for their refineries. Pipelines were built from Alberta through the Midwestern United States to Ontario and to the west coast of British Columbia. Exports to the U.S. increased dramatically.

Most of the oil companies exploring for oil in Alberta were of U.S. origin, and at its peak in 1973, over 78 per cent of Canadian oil and gas production was under foreign ownership and over 90 per cent of oil and gas production companies were under foreign control, mostly American. This foreign ownership spurred the National Energy Program under the Trudeau government.[8]

Major players

Although around a dozen companies operate oil refineries in Canada, only three companies – Imperial Oil, Shell Canada and Suncor Energy – operate more than one refinery and market products nationally. Other refiners generally operate a single refinery and market products in a particular region. Regional refiners include North Atlantic Refining in Newfoundland, Irving Oil in New Brunswick, Valero Energy in Quebec, Federated Co-operatives in Saskatchewan, Parkland in British Columbia, and Cenovus Energy in Alberta, BC, and Saskatchewan.[9] While Petro Canada was once owned by the Canadian government, it is now owned by Suncor Energy, which continues to use the Petro Canada label for marketing purposes. In 2007 Canada's three biggest oil companies brought in record profits of $11.75 billion, up 10 percent from $10.72 billion in 2006. Revenues for the Big Three climbed to $80 billion from about $72 billion in 2006. The numbers exclude Shell Canada and ConocoPhillips Canada, two private subsidiaries that produced almost 500,000 barrels per day in 2006.[10]

Divisions

Approximately 96% of Canadian oil production occurs in three provinces: Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2015 Alberta produced 79.2% of Canada's oil, Saskatchewan 13.5%, and the province of Newfoundland and Labrador 4.4%. British Columbia and Manitoba produced about 1% apiece.[11] The four Western Canada provinces of Alberta, British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Manitoba all produce their oil from the vast and oil rich Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, which is centered on Alberta but extends into the other three Western provinces and into the Northwest Territories. The province of Newfoundland and Labrador produces its oil from offshore drilling on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the western Atlantic Ocean.[12]

Alberta

Alberta is Canada's largest oil producing province, providing 79.2% of Canadian oil production in 2015. This included light crude oil, heavy crude oil, crude bitumen, synthetic crude oil, and natural-gas condensate. In 2015 Alberta produced an average of 492,265 cubic metres per day (3.1 Mbbl/d) of Canada's 621,560 cubic metres per day (3.9 Mbbl/d) of oil and equivalent production.[11] Most of its oil production came from its enormous oil sands deposits, whose production has been steadily rising in recent years. These unconventional deposits give Canada the world's third largest oil reserves, which are rivaled only by similar but even larger oil reserves in Venezuela, and conventional oil reserves in Saudi Arabia. Although Alberta has already produced over 90% of its conventional crude oil reserves, it has produced only 5% of its oil sands, and its remaining oil sands reserves represent 98% of Canada's established oil reserves.[13]

In addition to being the world's largest producer of oil sands bitumen in the world, Alberta is the largest producer of conventional crude oil, synthetic crude, natural gas and natural gas liquids products in Canada.

Oil sands

Alberta's oil sands underlie 142,200 square kilometres (54,900 sq mi) of land in the Athabasca, Cold Lake and Peace River areas in northern Alberta - a vast area of boreal forest which is larger than England. The Athabasca oil sands is the only large oil field in the world suitable for surface mining, while the Cold Lake oil sands and the Peace River oil sands must be produced by drilling.[14] With the advancement of extraction methods, bitumen and economical synthetic crude are produced at costs nearing that of conventional crude. This technology grew and developed in Alberta. Many companies employ both conventional strip mining and non-conventional methods to extract the bitumen from the Athabasca deposit. About 24 billion cubic metres (150 Gbbl) of the remaining oil sands are considered recoverable at current prices with current technology.[13] The city of Fort McMurray developed nearby to service the oil sands operations, but its remote location in the otherwise uncleared boreal forest became a problem when the entire population of 80,000 had to be evacuated on short notice because of the 2016 Fort McMurray Wildfire which enveloped the city and destroyed over 2,400 homes.[15]

Oil fields

Major oil fields are found in southeast Alberta (Brooks, Medicine Hat, Lethbridge), northwest (Grande Prairie, High Level, Rainbow Lake, Zama), central (Caroline, Red Deer), and northeast (heavy crude oil found adjacent to the oil sands.)

Structural regions include: Foothills, Greater Arch, Deep Basin.

Oil upgraders

There are five oil sands upgraders in Alberta which convert crude bitumen to synthetic crude oil, some of which also produce refined products such as diesel fuel. These have a combined capacity of 1.3 million barrels per day (210,000 m3/d) of crude bitumen.[16]

- The Shell Canada Scotford Upgrader at Fort Saskatchewan, Alberta has a capacity of 255,000 barrels per day (40,500 m3/d) of crude bitumen.

- The Suncor Energy upgrader near Fort McMurray, Alberta has a capacity of 440,000 barrels per day (70,000 m3/d) of crude bitumen.

- The Syncrude Mildred Lake upgrader near Fort McMurray has a capacity of 407,000 barrels per day (64,700 m3/d)

- The China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) Long Lake upgrader near Fort McMurray has a capacity of 72,000 barrels per day (11,400 m3/d)

- The Canadian Natural Resources Ltd (CNRL) Horizon upgrader near Fort McMurray has a capacity of 156,000 barrels per day (24,800 m3/d)

Oil pipelines

Since it is Canada's largest oil producing province, Alberta is the hub of Canadian crude oil pipeline systems. About 415,000 kilometres (258,000 mi) of Canada’s oil and gas pipelines operate solely within Alberta’s boundaries and fall under the jurisdiction of the Alberta Energy Regulator. Pipelines that cross provincial or international borders are regulated by the National Energy Board.[17] Major pipelines carrying oil from Alberta to markets in other provinces and US states include:[18]

- The Interprovincial Pipeline System (now called the Enbridge Pipeline System) was built in 1950 to transport crude oil from Edmonton, Alberta to Superior, Wisconsin where it supplies the Midwestern United States. In 1953 it was extended to Sarnia, Ontario to supply the Ontario market, and in 1976 to Montreal, Quebec.

- The Trans Mountain Pipeline System was built in 1953 to transport crude oil and refined products from Edmonton to Vancouver, BC. It also supplies feedstock to large US oil refineries in the state of Washington. Only crude oil and condensate are shipped to the United States.[19]

- The Norman Wells Pipeline (now owned by Enbridge) was built in 1985 to carry crude oil from Norman Wells, NWT to Zama City, Alberta, where it connects with the Alberta pipeline network.

- The Express Pipeline was built in 1997 to carry oil from the Alberta pipeline hub at Hardisty, Alberta to the US states of Montana, Utah, Wyoming and Colorado.

- The Keystone Pipeline was built in 2011 to carry oil from Hardisty, Alberta to the major US pipeline hub at Cushing, Oklahoma, where it connects to pipelines to Texas, Louisiana, and many of the Eastern United States.

Oil refineries

There are four oil refineries in Alberta with a combined capacity of over 458,200 barrels per day (72,850 m3/d) of crude oil. Most of these are located on what is known as Refinery Row in Strathcona County near Edmonton, Alberta, which supplies products to most of Western Canada. In addition to refined products such as gasoline and diesel fuel, the refineries and upgraders also produce off-gases, which are used as feedstock by nearby petrochemical plants.[16]

- The Suncor Energy (Petro Canada) refinery near Edmonton has a capacity of 142,000 barrels per day (22,600 m3/d) of crude oil.

- The Imperial Oil Strathcona Refinery near Edmonton has a capacity of 187,200 barrels per day (29,760 m3/d).

- The Shell Canada Scotford Refinery near Edmonton has a capacity of 100,000 barrels per day (16,000 m3/d). It is located adjacent to the Shell Scotford Upgrader, which provides it with feedstock.

- The Husky Lloydminster Refinery at Lloydminster, in eastern Alberta has a capacity of 29,000 barrels per day (4,600 m3/d). It is located across the provincial border from the Husky Lloydminster Heavy Oil Upgrader at Lloydminster, Saskatchewan, which provides it with feedstock. (Lloydminster is not a twin city but is chartered by both provinces as a single city that crosses the border.)

Other oil-related activities

Two of the largest producers of petrochemicals in North America are located in central and north central Alberta. In both Red Deer and Edmonton, world class polyethylene and vinyl manufacturers produce products shipped all over the world, and Edmonton's oil refineries provide the raw materials for a large petrochemical industry to the east of Edmonton. There are hundreds of small companies in Alberta dedicated to providing various services to this industry—from drilling to well maintenance, pipeline maintenance to seismic exploration.

While Edmonton (population 972,223 thousand in 2019[20]) is the provincial capital and is considered the pipeline, manufacturing, chemical processing, research and refining centre of the Canadian oil industry, its rival city Calgary (population 1.26 million[20]) is the main oil company head office and financial centre, with more than 960 senior and junior oil company offices. Calgary also has regional offices of all six major Canadian banks, some 4,300 petroleum, energy and related service companies, and 1,300 financial service companies, helping make it the second largest head office city in Canada after Toronto.[21]

- Oil and gas activity is regulated by the Alberta Energy Regulator (AER) (Formerly the Alberta Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB)and the Energy and Utility Board (EUB)).[22]

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan is Canada's second-largest oil-producing province after Alberta, producing about 13.5% of Canada's petroleum in 2015. This included light crude oil, heavy crude oil, and natural-gas condensate. Most of its production is heavy oil but, unlike Alberta, none of Saskatchewan's heavy oil deposits are officially classified as bituminous sands. In 2015 Saskatchewan produced an average of 83,814 cubic metres per day (527,000 bbl/d) oil and equivalent production.[11]

Oil fields

All of Saskatchewan's oil is produced from the vast Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, about 25% of which underlies the province. Lying toward the shallower eastern end of the later the sedimentary basin, Saskatchewan tends to produce more oil and less natural gas than other parts. It has four major oil-producing regions:[23]

- The Lloydminster area in west-central Saskatchewan has very large reserves of very heavy crude oil. (The oil field crosses the Alberta/Saskatchewan border, as do the production facilities.)[24]

- The Kindersley area in south-central Saskatchewan produces light crude oil using hydraulic fracturing from Saskatchewan's portion of the Bakken Formation, which also produces most of North Dakota's oil.

- The Swift Current area in southwest Saskatchewan produces mostly conventional oil.

- The Weyburn area in southeast Saskatchewan produces oil using carbon dioxide flooding in the Weyburn-Midale Carbon Dioxide Project, the world's largest carbon capture and storage project.

Oil upgraders

There are two heavy oil upgraders in Saskatchewan.[25]

- The NewGrade Energy Upgrader, part of the CCRL Refinery Complex in Regina, processes 8,740 cubic metres per day (55,000 bbl/d) of heavy oil from the Lloydminster area into synthetic crude oil.

- The Husky Energy Bi-Provincial Upgrader on the Saskatchewan side of Lloydminster processes 10,800 cubic metres per day (68,000 bbl/d) of heavy oil from Alberta and Saskatchewan to lighter crude oil. In addition to selling synthetic crude oil to other refineries, it supplies feedstock to the Husky Lloydminster Refinery on the Alberta side of the border. (Lloydminster is not twin cities but is a single bi-provincial city that straddles the Alberta/Saskatchewan border.)[24]

Oil refineries

The majority of the province's refining capacity is in a single complex in the provincial capital of Regina:[25]

- The CCRL Refinery Complex operated by Federated Co-operatives in Regina processes 8,000 cubic metres per day (50,000 bbl/d) into conventional refinery products. It receives much of its feedstock from the NewGrade upgrader.

- Moose Jaw Asphalt Inc. operates a 500 cubic metres per day (3,100 bbl/d) asphalt plant in Moose Jaw.

Oil and gas activity is regulated by the Saskatchewan Industry and Resources (SIR).[26]

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador is Canada's third largest oil producing province, producing about 4.4% of Canada's petroleum in 2015. This consisted almost exclusively of light crude oil produced by offshore oil facilities on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland. In 2015 these offshore fields produced an average of 27,373 cubic metres per day (172,000 bbl/d) of light crude oil.[11]

Oil fields

- The Hibernia oil field is located approximately 315 kilometres (196 mi) east-southeast of St. John's, Newfoundland. The field was discovered in 1979 and has been producing since 1997. The Hibernia Gravity Base Structure is the world's largest oil platform by weight since it has to withstand collisions by icebergs.

- The Terra Nova oil field is located 350 kilometres (220 mi) off the east coast of Newfoundland. The field was discovered in 1984 and has been producing since 2002. It uses a Floating Production Storage and Offloading (FPSO) vessel rather than a fixed platform to produce oil.

- The White Rose oil field is located 350 kilometres (220 mi) off the east coast of Newfoundland. The field was discovered in 1984 and has been producing since 2005. It uses a FPSO vessel to produce oil.

Oil refinery

Newfoundland has one oil refinery, the Come By Chance Refinery, which has a capacity of 115,000 barrels per day (18,300 m3/d). The refinery was built before the discovery of oil offshore Newfoundland to process cheap imported oil and sell the products mainly in the United States. Unfortunately the startup of the refinery in 1973 coincided with the 1973 oil crisis which quadrupled the price of the refinery's crude oil supply. This and technical problems caused the refinery to go bankrupt in 1976. It was restarted under new owners in 1986 and has gone through a series of owners until now, when it is operated by North Atlantic Refining Limited.[27] However, despite the fact that major oil fields were subsequently discovered offshore of Newfoundland, the refinery was not designed to process the type of oil they produced, and it did not process any Newfoundland oil at all until 2014. Until then all of Newfoundland's production went to refineries in the United States and elsewhere in Canada, while the refinery imported all its oil from other countries.[28]

British Columbia

British Columbia produced an average of 8,643 cubic metres per day (54,000 bbl/d) oil and equivalent in 2015, or about 1.4% of Canada's petroleum. About 38% of this liquids production was light crude oil, but most of it (62%) was natural-gas condensate.[11]

British Columbia's oil fields lie at the gas-prone northwest end of the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin, and its oil industry is secondary to the larger natural gas industry. Drilling for gas and oil takes place in Peace Country of north-eastern British Columbia, around Fort Nelson (Greater Sierra oil field), Fort St. John (Pink Mountain, Ring Border) and Dawson Creek

Oil and gas activity in BC is regulated by the Oil and Gas Commission (OGC).[29]

Oil refineries

BC has only two remaining oil refineries.[9]

- The Husky Energy Prince George Refinery in Prince George, BC processes 12,000 barrels per day (1,900 m3/d) of light oil produced locally in northeastern BC.

- The Chevron Canada Burnaby Refinery in the Vancouver suburb of Burnaby processes 55,000 barrels per day (8,700 m3/d) of light oil received from Alberta via the Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain Pipeline System.

There once were four oil refineries in the Vancouver area, but Imperial Oil, Shell Canada, and Petro Canada converted their refineries to product terminals in the 1990s and now supply the BC market from their large refineries near Edmonton, Alberta, which are closer to Canada's oil sands and largest oil fields.[30] Chevron's refinery is at risk of closure due to difficulties in getting oil supply from Alberta via the capacity-limited Trans Mountain Pipeline, its only pipeline link to the rest of Canada.[31]

In June 2016 Chevron put its oil refinery in Burnaby, BC up for sale, along with its fuel distribution network in British Columbia and Alberta. “The company acknowledges these are challenging times and we need to be open to changing market conditions and opportunities as they arise,” a company representative said. The refinery, which started production in 1935, has 430 employees. Chevron's offer to sell follows Imperial Oil's sale of 497 Esso gas stations in B.C. and Alberta. It is unclear what will happen if Chevron fails to sell its BC assets.[32]

Manitoba

Manitoba produced an average of 7,283 cubic metres per day (46,000 bbl/d) of light crude oil in 2015, or about 1.2% of Canada's petroleum production.[11]

Manitoba's oil production is in southwest Manitoba along the northeast flank of the Williston Basin, a large geological structural basin which also underlies parts of southern Saskatchewan, North Dakota, South Dakota and Montana. Unlike in Saskatchewan, very little of Manitoba's oil is heavy crude oil.[33]

- A few rigs drilling for oil in South western Manitoba

There are no oil refineries in Manitoba.

Northern Canada (onshore)

The Northwest Territories produced an average of 1,587 cubic metres per day (10,000 bbl/d) of light crude oil in 2015, or about 0.2% of Canada's petroleum production.[11] There is an historic large oil field at Norman Wells, which has produced most of its oil since it started producing 1937, and is continuing to produce at low rates. There used to be an oil refinery at Norman Wells, but it was closed in 1996 and all of the oil is now pipelined out to refineries in Alberta.[34]

- Drilling for tight oil in the Canol shale play near Norman Wells by Husky Energy and others.[35]

Northern Canada (offshore)

Extensive drilling was done in the Canadian Arctic during the 1970s and 1980s by such companies as Panarctic Oils Ltd., Petro Canada and Dome Petroleum. After 176 wells were drilled at a cost of billions of dollars, a modest 1.9 billion barrels (300×106 m3) of oil were found. None of the finds were big enough to pay for the multibillion-dollar production and transportation schemes required to bring the oil out, so all the wells which had been drilled were plugged and abandoned.[36] In addition, after the Deepwater Horizon explosion in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010, new rules were introduced which discouraged companies from drilling in the Canadian Arctic offshore.[37]

- There is currently no offshore oil production in northern Canada

- There is currently no offshore drilling in northern Canada

Eastern Canada (onshore)

Ontario produced an average of 157 cubic metres per day (1,000 bbl/d) of light crude oil in 2015, or less than 0.03% of Canada's petroleum production. Onshore production in other provinces east of Ontario was even more insignificant.[11]

Oil fields

Ontario was the centre of the Canadian oil industry in the 19th century. It had the oldest commercial oil well in North America (dug by hand in 1858 at Oil Springs, Ontario, a year before the Drake Well was drilled in Pennsylvania), and having the oldest producing oil field in North America (producing crude oil continuously since 1861). However, it reached its production peak and started to decline more than 100 years ago.[38]

- Sporadic drilling in southern Ontario

- Sporadic drilling in western Newfoundland

- Sporadic drilling in northern Nova Scotia and western Cape Breton Island

- Sporadic drilling in northern and eastern Prince Edward Island

Oil pipelines

Canada had one of the world’s first oil pipelines in 1862 when a pipeline was built to deliver oil from Petrolia, Ontario to refineries at Sarnia, Ontario. However, Ontario's oil fields began to decline toward the end of the 19th century, and by World War II Canada was importing 90% of its oil. By 1947, only three Canadian crude oil pipelines existed. One was built to handle only Alberta production. A second moved imported crude from coastal Maine to Montreal, while the third brought American oil into Ontario.[39] However, in 1947 the first big oil discovery was made in Alberta when Leduc No. 1 struck oil 40 kilometres (25 mi) southwest of central Edmonton, Alberta. It was followed by many even larger discoveries in Alberta, so pipelines were built to take the newly discovered oil to refineries in the American Midwest and from there to refineries in Ontario.[40]

- The Interprovincial Pipeline (now known as Enbridge) was built in 1950 to take Alberta oil to US refineries. In 1953 it was extended through the US to Sarnia, Ontario and in 1956 to Toronto. This made it the longest crude oil pipeline in the world.

- The Interprovincial Pipeline was extended to Montreal in 1976 after the 1973 oil crisis interrupted foreign oil supplies to Eastern Canada.

- The Portland–Montreal Pipe Line was built during World War II to bring imported oil from the marine terminal at South Portland, Maine through the United States to Montreal. As of 2016, the pipeline is no longer operational since the only remaining Montreal Refinery, is now owned by Suncor Energy, which produces enough oil to meet its needs from the Canadian oil sands.[41]

Oil refineries

Despite having very little oil production, Eastern Canada has a large number of oil refineries. The ones in Ontario were built close to the historic oil fields of southern Ontario; the ones in provinces to the east were built to process oil imported from other countries. After Leduc No. 1 was discovered in 1947, the much larger oil fields in Alberta began to supply Ontario refineries. After the 1973 oil crisis drastically increased the price of imported oil, the economics of refineries became unfavorable, and many of them closed. In particular, Montreal, which had six oil refineries in 1973, now has only one.[42]

- Nanticoke Refinery - (Imperial Oil), 112,000 bbl/d (17,800 m3/d)

- Sarnia - (Imperial Oil), 115,000 bbl/d (18,300 m3/d)

- Sarnia - (Suncor Energy), 85,000 bbl/d (13,500 m3/d)

- Corunna - (Shell Canada), 72,000 bbl/d (11,400 m3/d)

- Mississauga - (Suncor Energy), 15,600 bbl/d (2,480 m3/d)

- Montreal Refinery - (Suncor Energy), 140,000 bbl/d (22,000 m3/d).

- Lévis - (Valero Energy Corporation)), 265,000 bbl/d (42,100 m3/d)

- Irving Oil Refinery, Saint John (Irving Oil), 300,000 bbl/d (48,000 m3/d)

- North Atlantic Refinery, Come By Chance - (North Atlantic Refining), 115,000 bbl/d (18,300 m3/d)

Eastern Canada (offshore)

The province of Newfoundland and Labrador is Canada's third largest oil producer with 27,373 cubic metres per day (172,000 bbl/d) of light crude oil from its Grand Banks offshore oil fields in 2015, about 4.4% of Canada's petroleum. See the Newfoundland and Labrador section above for details. Most of the other offshore production was in the province of Nova Scotia, which produced 438 cubic metres per day (2,750 bbl/d) of natural gas condensate from its Sable Island offshore natural gas fields in 2015, or about 0.07% of Canada's petroleum.[11]

- Offshore oil drilling and production at Hibernia, Terra Nova, and White Rose fields off the coast of Newfoundland

- Offshore gas drilling and production on Sable Island fields off the coast of Nova Scotia

- Sporadic drilling along continental shelf off Nova Scotia (e.g. Shelburne Basin)

- Sporadic drilling in Laurentian fan at southern end of Cabot Strait

- Sporadic drilling in eastern Northumberland Strait

Long-term outlook

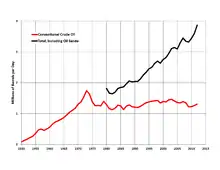

- Oil Production In North America

Canadian conventional oil production peaked in 1973, but oil sands production is forecast to increase until at least 2020

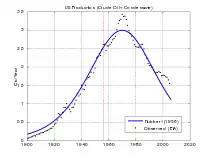

Canadian conventional oil production peaked in 1973, but oil sands production is forecast to increase until at least 2020 US oil production (crude oil only) and Hubbert high estimate.

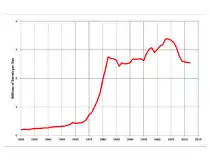

US oil production (crude oil only) and Hubbert high estimate. Mexican production peaked in 2004 and is now in decline

Mexican production peaked in 2004 and is now in decline

Broadly speaking Canadian conventional oil production (via standard deep drilling) peaked in the mid-1970s, but East Coast offshore basins being exploited in Atlantic Canada did not peak until 2007 and are still producing at relatively high rates.[43]

Production from the Alberta oil sands is still in its early stages and the province's established bitumen resources will last for generations into the future. The Alberta Energy Regulator estimates that the province has 50 billion cubic metres (310 billion barrels) of ultimately recoverable bitumen resources. At the 2014 production rate of 366,300 m3/d (2.3 million bbl/d), they would last for about 375 years. The AER projects that bitumen production will increase to 641,800 m3/d (4.0 million bbl/d) by 2024, but at that rate they would still last for about 213 years.[44]: 3-10–3-26 Because of the enormous size of the known oil sands deposits, economic, labor, environmental, and government policy considerations are the constraints on production rather than finding new deposits.

In addition, the Alberta Energy Regulator has recently identified over 67 billion cubic metres (420 Gbbl) of unconventional shale oil resources in the province.[44]: 4–3 This volume is larger than the province's oil sands resources, and if developed would give Canada the largest crude oil reserves in the world. However, due to the recent nature of the discoveries there are not yet any plans to develop them.

Oil fields of Canada

These oil fields are or were economically important to the Canadian economy:

- Oil Springs, Ontario

- Turner Valley oil field, Alberta

- Leduc oil field, Alberta

- Pembina oil field, Alberta

- Athabasca oil sands, Alberta

- Peace River oil sands, Alberta

- Cold Lake oil sands, Alberta

- Duvernay Formation, Alberta (shale oil and gas)

- Montney Formation, Alberta, BC (shale oil and gas)

- Hibernia oil field, offshore Newfoundland

- Terra Nova oil field, offshore Newfoundland

- White Rose oil field, offshore Newfoundland

Upstream, midstream and downstream components of Canadian petroleum industry

There are three components of the Canadian petroleum industry: upstream, midstream and downstream.

Upstream

The upstream oil sector is also commonly known as the exploration and production (E&P) sector.[45][46][47]

The upstream sector includes the searching for potential underground or underwater crude oil and natural gas fields, drilling of exploratory wells, and subsequently drilling and operating the wells that recover and bring the crude oil and/or raw natural gas to the surface. With the development of methods for extracting methane from coal seams,[48] there has been a significant shift toward including unconventional gas as a part of the upstream sector, and corresponding developments in liquified natural gas (LNG) processing and transport. The upstream sector of the petroleum industry includes Extraction of petroleum, Oil production plant, Oil refinery and Oil well.

Midstream

The midstream sector involves the transportation, storage, and wholesale marketing of crude or refined petroleum products. Canada has a large network of pipelines - over 840,000 km - that transport crude oil and natural gas across the country.[49] There are four main pipeline groups: gathering, feeder, transmission, and distribution pipelines. Gathering pipelines transport crude oil and natural gas from wells drilled in the subsurface to oil batteries or natural gas processing facilities. The majority of these pipelines are found in petroleum producing areas in Western Canada.[50] Feeder pipelines move crude oil, natural gas, and natural gas liquids (NGLs) from the batteries, processing facilities, and storage tanks to the long-distance portion of the transportation system: transmission pipelines. These are the major carriers of crude oil, natural gas, and NGLs within provinces and across provincial or international borders, where the products are either sent to refineries or exported to other markets.[50] Finally, distribution pipelines are the conduit for delivering natural gas to downstream customers, such as local utilities, and then further distributed to homes and businesses. If pipelines are near capacity or non-existent in certain areas, crude oil is then transported over land by rail or truck, or over water by marine vessels.

The midstream operations are often taken to include some elements of the upstream and downstream sectors. For example, the midstream sector may include natural gas processing plants which purify the raw natural gas as well as removing and producing elemental sulfur and natural gas liquids (NGL) as finished end-products. Midstream service providers in Canada refer to Barge companies, Railroad companies, Trucking and hauling companies, Pipeline transport companies, Logistics and technology companies, Transloading companies and Terminal developers and operators. Development of the massive oil sand reserves in Alberta would be facilitated by enhancing the North American pipeline network which would transport dilbit to refineries or export facilities.[51]

Downstream

The downstream sector commonly refers to the refining of petroleum crude oil and the processing and purifying of raw natural gas,[45][46][47] as well as the marketing and distribution of products derived from crude oil and natural gas. The downstream sector touches consumers through products such as gasoline or petrol, kerosene, jet fuel, diesel oil, heating oil, fuel oils, lubricants, waxes, asphalt, natural gas, and liquified petroleum gas (LPG) as well as hundreds of petrochemicals. Midstream operations are often included in the downstream category and considered to be a part of the downstream sector.

Crude oil

Crude oil, for example, Western Canadian Select (WCS) is a mixture of many varieties of hydrocarbons and most usually has many sulfur-containing compounds. The refining process converts most of that sulfur into gaseous hydrogen sulfide. Raw natural gas also may contain gaseous hydrogen sulfide and sulfur-containing mercaptans, which are removed in natural gas processing plants before the gas is distributed to consumers. The hydrogen sulfide removed in the refining and processing of crude oil and natural gas is subsequently converted into byproduct elemental sulfur. In fact, the vast majority of the 64,000,000 metric tons of sulfur produced worldwide in 2005 was byproduct sulfur from refineries and natural gas processing plants.[52][53]

Export capacity

Total Canadian crude oil production, most of which is coming from the Western Canada Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), is forecast to increase from 3.85 million barrels per day (b/d) in 2016 to 5.12 million b/d by 2030.[54] Supply from the Alberta oil sands accounts for most of the growth and is expected to increase from 1.3 million b/d in 2016 to 3.7 million b/d in 2030.[54] Bitumen from the oil sands requires blending with a diluent in order to decrease its viscosity and density so that it can easily flow through pipelines. The addition of diluent will add an estimated 200,000 b/d to the total volumes of crude oil in Canada, for a total of 1.5 million extra barrels per day requiring the creation of additional transport capacity to markets.[54] The current takeaway capacity in Western Canada is tight, as oil producers are beginning to outpace the movement of their products.

Pipeline capacity measurements are complex and subject to variability. They depend on a number of factors, such as the type of product being transported, the products it is mixed with, pressure reductions, maintenance, and pipeline configurations.[55] The major oil pipelines exiting Western Canada have a design transport capacity of 4.0 million b/d.[54] In 2016, however, the pipeline capacity was estimated at 3.9 million b/d,[1] and in 2017 the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) estimated the pipeline capacity to be 3.3 million b/d.[54] The lack of available pipeline capacity for petroleum forces oil producers to look to alternative transport methods, such as rail.

Crude-by-rail shipments are expected to increase as existing pipelines reach capacity and proposed pipelines experience approval delays.[56] The rail loading capacity for crude in Western Canada is close to 1.2 million b/d, although this varies depending on several factors including the length of the unit trains, size and type of railcars used, and the types of crude oil loaded.[57] Other studies, however, estimate the current rail loading capacity in Western Canada to be 754,000 b/d.[54] The International Energy Agency (IEA) forecasts that crude-by-rail exports will increase from 150,000 b/d in late 2017 to 390,000 b/d in 2019, which is much greater than the record high of 179,000 b/d in 2014.[58] The IEA also warns that rail shipments could reach as high as 590,000 b/d in 2019 unless producers store their produced crude during peak months.[58] The oil industry in the WCSB may need to continue to rely on rail in the forecastable future, as no major new pipeline capacity is expected to be available before 2019.[57] The capacity - to a certain extent - is there, but producers must be willing to pay a premium to move crude by rail.

Getting to tidewater

Canada has had access to western tide water since 1953, with a capacity of roughly 200,000 - 300,000 bpd via the Kinder Morgan Pipeline. There is a myth perpetuated in Canadian media that Canadian WCS oil producers will have better access to “international prices” with greater access to tidewater,[59] however, this claim does not take into account existing access. Shipments to Asia reached their peak in 2012 when the equivalent of nine fully loaded tankers of oil left Vancouver for China. Since then, oil exports to Asia have completely dropped off to the point at which China imported only 600 barrels of oil in 2017 . With regard to the claim that Canada does not have access to “international prices”, many economists decry the concept that Canada does have access to the globalized economy as ridiculous and attribute the price differential to the costs of shipping heavy, sour crude thousands of kilometres, compounded by over supply in the destinations able to process aforementioned oil.[60] Due to a doubling of a “production and export” model bet on by the biggest players in the tar sands, producers have recently (2018) encountered an over supply problem, and have sought further government subsidies to lessen the blow of their financial miscalculations earlier this decade. Preferred access ports include the US Gulf ports via the Keystone XL pipeline to the south, the British Columbia Pacific coast in Kitimat via the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines, and the Trans Mountain line to Vancouver, BC. Frustrated by delays in getting approval for Keystone XL, the Enbridge Northern Gateway Pipelines, and the expansion of the existing Trans Mountain line to Vancouver, Alberta has intensified exploration of northern projects, such as building a pipeline to the northern hamlet of Tuktoyatuk near the Beaufort Sea, "to help the province get its oil to tidewater, making it available for export to overseas markets".[61] Under Prime Minister Stephen Harper, the Canadian government spent $9 million by May 2012, and $16.5 million by May 2013, to promote Keystone XL.[62] In the United States, Democrats are concerned that Keystone XL would simply facilitate getting Alberta oil sands products to tidewater for export to China and other countries via the American Gulf Coast of Mexico.[62]

In 2013, Generating for Seven Generations (G7G) and AECOM received $1.8 million in funding from Alberta Energy to study the feasibility of building a railway from northern Alberta to the Port of Valdez, Alaska.[63] The proposed 2,440-km railway would be capable of transporting 1 million to 1.5 million b/d of bitumen and petroleum products, as well as other commodities, to tidewater[64] (avoiding the tanker ban along British Columbia's northern coast). The last leg of the route - Delta Junction through the coastal mountain range to Valdez - was not deemed economically feasible by rail; an alternative, however, may be the transfer of products to the underutilized Trans Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) to Valdez.[64]

Port Metro Vancouver has a number of petroleum terminals, including Suncor Burrard Terminal in Port Moody, Imperial Oil Ioco Terminal in Burrard Inlet East, and Kinder Morgan Westridge, Shell Canada Shellburn, and Chevron Canada Stanovan terminals in Burnaby.[65]

Pipeline versus rail debate

The public debate surrounding the trade-offs between pipeline and rail transportation has been developing over the past decade as the amount of crude oil transported by rail has increased.[66][56] It was invigorated in 2013 after the deadly Lac-Mégantic disaster in Quebec when a freight train derailed and spilled 5.56 million litres[67] of crude oil, which resulted in explosions and fires that destroyed much of the town's core. That same year, a train carrying propane and crude derailed near Gainford, Alberta, resulting in two explosions but no injuries or fatalities.[68] These rail accidents, among other examples, have raised concerns that the regulation of rail transport is inadequate for large-scale crude oil shipments. Pipeline failures also occur, for instance, in 2015 a Nexen pipeline ruptured and leaked 5 million litres of crude oil over approximately 16,000 m2 at the company's Long Lake oilsands facility south of Fort McMurray.[69] Although both pipeline and rail transportation are generally quite safe, neither mode is without risk. Numerous studies, however, indicate that pipelines are safer, based on the number of occurrences (accidents and incidents) weighed against the quantity of product transported.[70][71] Between 2004 and 2015, the likelihood of rail accidents in Canada was 2.6 times greater than for pipelines per thousand barrels of oil equivalents (Mboe).[72] Natural gas products were 4.8 times more likely to have a rail occurrence when compared to similar commodities transported by pipelines.[72] Critics question if pipelines carrying diluted bitumen from Alberta's oil sands are more likely to corrode and cause incidents, but evidence shows the risk of corrosion being no different from that of other crude oils.[73]

Costs

A 2017 study by the National Bureau of Economic Research found that contrary to popular belief, the sum of air pollution and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions costs is substantially larger than accidents and spill costs for both pipelines and rail.[74] For crude oil transported from the North Dakota Bakken Formation, air pollution and greenhouse gas emission costs are substantially larger for rail compared to pipeline. For pipelines and rail, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration's (PHMSA) central estimate of spill and accident costs is US$62 and US$381 per million-barrel miles transported, respectively.[75] Total GHG and air pollution costs are 8 times higher than accident and spills costs for pipelines (US$531 vs US$62) and 3 times higher for rail (US$1015 vs US$381).[75]

Finally, transporting oil and gas by rail is generally more expensive for producers than transporting it by pipeline. On average, it costs between US$10-$15 per barrel to transport oil and gas by rail compared to $5 a barrel for pipeline.[76][77] In 2012,16 million barrels of oil were exported to USA by rail. By 2014, that number increased to 59 million barrels.[78] Although quantities decreased to 48 million in 2017, the competitive advantages offered by rail, particularly its access to remote regions as well as lack of regulatory and social challenges compared with building new pipelines, will likely make it a viable transportation method for years to come.[78] Both forms of transportation play a role in moving oil efficiently, but each has its unique trade-offs in terms of the benefits it offers.

Regulatory agencies in Canada

The jurisdiction over the petroleum industry in Canada, which includes energy policies regulating the petroleum industry, is shared between the federal and provincial and territorial governments. Provincial governments have jurisdiction over the exploration, development, conservation, and management of non-renewable resources such as petroleum products. Federal jurisdiction in energy is primarily concerned with regulation of inter-provincial and international trade (which included pipelines) and commerce, and the management of non-renewable resources such as petroleum products on federal lands.[79]

Natural Resources Canada (NRCan)

Oil and Gas Policy and Regulatory Affairs Division (Oil and Gas Division) of Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) provides an annual review of and summaries of trending of crude oil, natural gas and petroleum product industry in Canada and the United States (US)[80]

National Energy Board

Until February 2018, the petroleum industry was also regulated by the National Energy Board (NEB), an independent federal regulatory agency. The NEB regulated inter-provincial and international oil and gas pipeline transport and power lines; the export and import of natural gas under long-term licenses and short-term orders, oil exports under long-term licenses and short-term orders (no applications for long-term exports have been filed in recent years), and frontier lands and offshore areas not covered by provincial/federal management agreements.

In 1985, the federal government and the provincial governments in Alberta, British Columbia and Saskatchewan agreed to deregulate the prices of crude oil and natural gas. Offshore oil Atlantic Canada is administered under joint federal and provincial responsibility in Nova Scotia and Newfoundland and Labrador.[79]

Provincial regulatory agencies

There were few regulations in the early years of the petroleum industry. In Turner Valley, Alberta for example, where the first significant field of petroleum was found in 1914, it was common to extract a small amount of petroleum liquids by flaring off about 90% of the natural gas. According to a 2001 report that amount of gas that would have been worth billions. In 1938 the Alberta provincial government responded to the conspicuous and wasteful burning of natural gas. By the time crude oil was discovered in the Turner Valley field, in 1930, most of the free gas cap had been flared off.[81] The Alberta Petroleum and Natural Gas Conservation Board (today known as the Energy Resources Conservation Board) was established in 1931 to initiate conservation measures but by that time the Depression caused a waning of interest in petroleum production in Turner Valley which was revived from 1939 to 1945.[82]

See also

References

- "Crude oil facts". Government of Canada.

- "U.S. Imports by Country of Origin". Energy Information Administration.

- Canadian Rig Locator Archived 2006-02-15 at the Wayback Machine

- "REFINED PETROLEUM PRODUCTS - IMPORTS". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019.

- "REFINED PETROLEUM PRODUCTS - EXPORTS". Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on January 9, 2019.

- Oil Museum of Canada

- "Six Historical Events in the First 100 Years of Canada's Petroleum Industry". Petroleum Historical Society of Canada. 2009.

- Peter Tertzakian (Jul 25, 2012). "Canada again a focus of a new Great Scramble for oil". The Globe and Mail.

- "Canadian Refineries". Natural Resources Canada. Archived from the original on May 23, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- Vancouver Sun. Record Profits for Canada's big oil companies Archived 2009-02-10 at the Wayback Machine

- "Estimated Production of Canadian Crude Oil and Equivalent". National Energy Board. 2015. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- "Oil Supply and Demand". Natural Resources Canada. 11 February 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- "ST98-2016: Alberta's Energy Reserves and Supply/Demand Outlook". Alberta Energy Regulator. 2016. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- "Oil Sands". Alberta Energy. Archived from the original on 2015-02-14. Retrieved 2016-05-20.

- "A Week In Hell - How Fort McMurray Burned". The Globe & Mail. May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- "Upgraders and Refineries Facts and Stats" (PDF). Government of Alberta. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- "Pipelines". Alberta Energy Regulator. Archived from the original on 2016-06-11. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- "History of Pipelines". Canadian Energy Pipeline Association. Retrieved 2016-05-29.

- "Trans Mountain Pipeline System". Kinder Morgan Canada. Archived from the original on 2016-05-23. Retrieved 2016-05-30.

- "Population of census metropolitan areas". Statistics Canada. 26 February 2014. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- Burton, Brian (2012-04-30). "Calgary a head-office hub – second only to Toronto". Calgary Herald. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- Alberta Energy Resources Conservation Board (ERCB)

- "Oil and Gas Industry". Encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina. Retrieved 2016-05-23.

- "Lloydminster - Black Oil Capital of Canada". Heavy Oil Science Centre. August 1982. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- "Energy and Mineral Resources of Saskatchewan - Oil". Government of Saskatchewan. Archived from the original on 2016-06-24. Retrieved 2016-05-22.

- "Oil and Gas". Saskatchewan.

- "History of the Refinery at Come by Chance". North Atlantic Refining Limited.

- "Come By Chance refinery now processing oil pumped off Newfoundland". CBC News. May 20, 2015.

- "British Columbia Oil and Gas Commission (OGC)". Government of British Columbia.

- Jennifer, Moreau (April 6, 2012). "Who's moving oil on the Burrard Inlet?". Burnaby Now.

- Jennifer, Moreau (February 2, 2012). "Burnaby's Chevron refinery in peril?". Burnaby Now.

- Penner, Derrick (June 17, 2016). "Chevron puts Burnaby oil refinery, B.C. distribution network on sales block". Vancouver Sun.

- "Manitoba Oil Facts". Government of Manitoba. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Campbell, Darren (2007). "Staying power". Nature. Up Here Business. 446 (7134): 468. doi:10.1038/nj7134-468a. PMID 17410650.

- Francis, Diane (September 20, 2013). "The Northwest Territories Strikes Oil and Changes Energy Prospects". HuffPost.

- Jaremko, Gordon (April 4, 2008). "Arctic fantasies need reality check: Geologist knows risks of northern exploration". The Edmonton Journal. Archived from the original on June 12, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

- "Review of offshore drilling in the Canadian Arctic". National Energy Board. December 2011. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- Row, James (September 17, 2008). "Ontario oil sector keeps pumping away" (PDF). Business Edge News.

- "Pipelines in Canada". Natural Resources Canada. 29 October 2012. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- "Enbridge Inc. - Company Profile". Encyclopedia of Small Business. Retrieved 2016-05-31.

- Tom Bell (March 8, 2016). "South Portland-to-Montreal crude oil pipeline shut down". The Portland Press Herald. Associated Press. Retrieved May 20, 2016.

- "REFINERY CLOSURES - CANADA 1970-2015". Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. Archived from the original on 2016-08-08. Retrieved 2016-05-26.

- "Total Oil Production, Barrels - Newfoundland and Labrador - November 1997 to Date" (PDF). Economics and Statistics Branch (Newfoundland & Labrador Statistics Agency). Retrieved 2014-11-14.

- "ST98-2015: Alberta's Energy Reserves 2014 and Supply/Demand Outlook 2015–2024" (PDF). aer.ca. Alberta Energy Regulator. June 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-30. Retrieved 2016-06-20.

- Petroleum industry

- Upstream, midstream & downstream Archived 2014-01-07 at the Wayback Machine

- Industry Overview from the website of the Petroleum Services Association of Canada (PSAC)

- Coalbed Methane Basic Information

- "Pipelines Across Canada". www.nrcan.gc.ca. 22 July 2016. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Board, Government of Canada, National Energy. "NEB – Canada's Pipeline Transportation System 2016". www.neb-one.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Ian Austen (August 25, 2013). "Canadian Documents Suggest Shift on Pipeline". The New York Times. Retrieved August 26, 2013.

- Sulfur production report by the United States Geological Survey

- Discussion of recovered byproduct sulfur

- "2017 CAPP Crude Oil Forecast, Markets & Transportation". Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Board, Government of Canada, National Energy. "NEB – Canadian Pipeline Transportation System - Energy Market Assessment". www.neb-one.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-04-06.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Varcoe: As Canada waits for pipelines, record volumes of oil move by rail". Calgary Herald. 2018-07-31. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- Board, Government of Canada, National Energy. "NEB – Market Snapshot: Major crude oil rail loading terminals in the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin". www.neb-one.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - CBC News (March 5, 2018). "Crude-by-rail shipments in Canada to more than double by 2019, says international agency". The Canadian Press. Retrieved April 6, 2018.

- Wilt, James (April 19, 2018). "The Myth of The Asian Market for Alberta's Oil". The Narwhal. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- "Gluts, price differential: Six things to know about Canada's oil-price gap". financialpost. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- Hussain, Yadullah (25 April 2013). "Alberta exploring at least two oil pipeline projects to North". Financial Post.

- Goodman, Lee-Anne (2013-05-22). "Republicans aim to take Keystone XL decision out of Obama's hands". CTVNews. Retrieved 2023-04-29.

- Bennett, Nelson. "Oil-by-rail-to-Alaska bid could nearly bypass B.C." Western Investor. Retrieved 2018-04-09.

- The Van Horne Institute (2015). "Alberta to Alaska Railway: Pre-Feasibility Study" (PDF): 33.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - "Port Metro Vancouver - Bulk". Archived from the original on 2013-05-13. Retrieved 2013-05-23.

- "Data shows where real risks lie in moving oil by pipeline or rail: op-ed". Fraser Institute. 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2018-11-22.

- Dunford, David Tyler (2017-02-01). "The Lac-Mégantic Derailment, Corporate Regulation, and Neoliberal Sovereignty". Canadian Review of Sociology. 54 (1): 69–88. doi:10.1111/cars.12139. ISSN 1755-618X. PMID 28220679.

- Riedlhuber, Dan (October 20, 2013). "Alberta train derailment renews fears over moving oil by rail". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 7, 2018.

- "Pipeline leak spills 5 million litres from Alberta oilsands | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2018-04-07.

- Green & Jackson (August 2015). "Safety in the Transportation of Oil and Gas: Pipelines or Rail?". Fraser Research Bulletin: 14.

- Furchtgott-Roth, Diana (June 2013). "Pipelines Are Safest for Transportation of Oil and Gas". Manhattan Institute for Policy Research. 23: 10.

- Safety First : Intermodal Safety for Oil and Gas Transportation. Green, Kenneth P., Jackson, Taylor., Canadian Electronic Library (Firm). Vancouver, BC, CA. 2017. ISBN 9780889754485. OCLC 1001019638.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - 6 Summary of Results | TRB Special Report 311: Effects of Diluted Bitumen on Crude Oil Transmission Pipelines | The National Academies Press. 2013. doi:10.17226/18381. ISBN 978-0-309-28675-6.

- Clay, Karen; Jha, Akshaya; Muller, Nicholas; Walsh, Randall (September 2017). "The External Costs of Transporting Petroleum Products by Pipelines and Rail: Evidence From Shipments of Crude Oil from North Dakota". doi:10.3386/w23852. S2CID 117652684.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - DOT/PHMSA. "Final Regulatory Impact Analysis (RIA)- Hazardous Materials: Enhanced Tank Car Standards and Operational Controls for High-Hazard Flammable Trains; Final Rule". www.regulations.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- Congressional Research Service (Dec 2014). "U.S. Rail Transportation of Crude Oil: Background and Issues for Congress". CRS Report Prepared for Members and Committees of Congress.

- "Crude oil will continue rolling by train". Fuel Fix. 2013-07-28. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

- Board, Government of Canada, National Energy. "NEB – Canadian Crude Oil Exports by Rail – Monthly Data". www.neb-one.gc.ca. Retrieved 2018-04-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - "Legal and Policy Frameworks - Canada". North America: The Energy Picture. Natural Resources Canada. January 2006. Archived from the original on 2011-08-03. Retrieved 2008-08-16.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-03. Retrieved 2015-03-24.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - Hyne, Norman J. (2001). Nontechnical Guide to Petroleum Geology, Exploration, Drilling and Production, 2nd Ed. PennWell. pp. 410–411. ISBN 0-87814-823-X.

- The Applied History Research Group (1997). "The Turner Valley Oil Era: 1913-1946". Calgary and Southern Alberta. The University of Calgary. Archived from the original on 2008-06-18. Retrieved 2008-08-18.

Further reading

- Foster, Peter (1979). The Blue-Eyed Sheiks: the Canadian Oil Establishment. Don Mills, Ontario: Collins Publishing. ISBN 9780002166089.