Grand River Railway

The Grand River Railway (reporting mark GRNR) was an interurban electric railway (known as a radial in Ontario) in what is now the Regional Municipality of Waterloo, in Southwestern Ontario, Canada.

.jpg.webp) Grand River Railway locomotive 230 in September 1963, after the end of passenger service and dieselization of the line. | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Headquarters | Preston, Ontario |

| Reporting mark | GRNR |

| Locale | Waterloo County, Ontario, Canada |

| Dates of operation | 1914–1931 |

| Predecessor | |

| Successor | Canadian Pacific Electric Lines CP Waterloo Subdivision |

| Technical | |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Overhead, originally 600 V DC, 1500 V DC after 1921 |

| Length | 30 km (19 mi)[1] |

Grand River Railway | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

Preston and Berlin Railway

Starting in the 1850s, Canada West (today's province of Ontario) began to see its first railways. Of these, the first chartered was the Great Western Railway, which was completed in 1853-54 and connected Niagara Falls to Windsor via London and Hamilton, linking many contemporary centres of population, industry, and trade. in 1855, a branch line was built to Toronto, which fell on the east side of the Grand River, connecting towns and villages in the area such as Galt, Hespeler, Preston, and Guelph. Galt and Guelph in particular were developing into significant urban areas in the region.

In the following year of 1856, the Grand Trunk Railway, the dominant railway in Canada East (today's province of Québec), made a major westward push by acquiring the fledgling Toronto and Guelph Railroad, whose line was then under construction, and extended this line to Sarnia through Berlin (today's Kitchener). Once complete, this made Guelph a major three-way rail junction. In this climate of rapid rail development, ambitious town boosters sought to have their town or village also become a railway junction in the hopes that it would transform it into a city overnight. The merchants of Preston, who saw themselves as being in direct competition with those of Galt, quickly worked to establish a railway which would connect the Great Western and Grand Trunk through their own town and the town of Berlin across the river. In 1857, their dream would be realized with the completion of the Preston and Berlin Railway, which was routed through the small mill towns of Doon and German Mills, with a bridge crossing the Grand River north of Blair. This initial attempt to connect the two cities was short-lived, however, as the bridge was damaged by ice flows in January 1858, and the railway was operational for less than three months. The surviving sections of the line were sold to the Grand Trunk Railway, which instead chose to extend the line south to Galt through the village of Blair in 1872, bypassing Preston entirely.[2]

Early street railways

The Berlin and Waterloo Street Railway began operation in 1888 as a firmly 19th-century-style horse-drawn street railway. However, things would quickly change; by the 1890s, the tone of railway fever had shifted, and many radial railways were being developed throughout Canada and the United States, as cities like Toronto and New York accelerated the process of amalgamation of nearby villages and towns, and urban businesses sought out customers travelling to the city from the suburbs. These systems were typically electrified rather than steam-powered, and used tram-style rolling stock to move a relatively small number of passengers at frequent headways within a region, rather than more traditional passenger trains pulled by dedicated locomotives, which were largely relegated to long-haul trips. Growing towns and cities sought the ideal hybrid system of streetcars and railways: a light rail service which could easily shift from street rails to dedicated rail corridors and back again, allowing them to connect to important destinations in downtown areas while also being fast enough to connect cities to each other at the speed expected of contemporary passenger rail. These systems were often also known as interurbans due to the appeal of easily connecting neighbouring cities together with a regional rail line, often municipally owned and operated.

The first such railway in the region was the Galt and Preston Street Railway (G&P), which began operations with half-hourly service in 1894.[3] With Preston boosters still concerned about the potential effect of the railway on their town's economy, the plan ensured that Preston would be the location of many operational aspects of the railway, including the power house, car barns, and machine shops. A year later, in 1895, it was extended to Hespeler and renamed the Galt, Preston and Hespeler Street Railway (GP&H),[4] connecting the three largest settlements of what 80 years later would become the amalgamated city of Cambridge. In the same year, the Berlin and Waterloo Street Railway began to take steps to modernize its service by converting its horse cars to run on electric power. This proved unsuitable and a consortium of local businessmen, impatient at the lack of progress, purchased the railway and outfitted it with new, purpose-built electric trams, which were manufactured in Peterborough.

Canadian Pacific Railway influence

The Canadian Pacific Railway had from the beginning taken an interest in the Galt and Preston Street Railway, then the Galt, Preston and Hespeler Street Railway, as an electric freight service would provide a convenient way to serve smaller freight customers profitably, due to the ability for electric locomotives to reverse without requiring a loop, as steam locomotives did. The G&P's charter, ostensibly mostly to provide Preston travellers with a connection to the Canadian Pacific via Galt, as well as to facilitate regional passenger transportation in general, provided Canadian Pacific an opportunity to "piggyback" and increase its freight operations. The Grand River area had long been dominated by the Grand Trunk Railway, and Canadian Pacific sought ways to compete with the Grand Trunk. With its close relationship with Canadian Pacific, the G&P provided free freight service to Canadian Pacific's depot in Galt, drawing business away from the Grand Trunk and provoking an all-out freight war. In the truce agreed upon by both companies, Berlin remained Grand Trunk territory, while both railways would continue to serve Galt.[5] Canadian Pacific, meanwhile, took control of the GP&H indirectly by buying up a controlling stake in the company through a proxy, its own General Superintendent J. W. Leonard, already laying the groundwork for the undermining of its agreement with the Grand Trunk.[6]

By the turn of the century, there was an explosion in plans for railway lines to serve Berlin, Preston, and Galt; the Hamilton Radial Electric Railway announced a plan to build a connection to Berlin, while the plan for a Preston-to-Berlin connection via Doon and Blair was revived. In 1903, the Preston and Berlin Street Railway, which had been chartered in 1894 and whose construction had begun in 1900, was leased by the GP&H, and began operations in 1904.[7] A Berlin, Waterloo, Wellesley, and Lake Huron Railway was being promoted at the same time, which was planned to serve a staggering number of destinations from Berlin northward to Lake Huron. However, with many of its promoters and supporters being connected to Canadian Pacific and the GP&H, and without the funds for such an ambitious project, scholars like Peter F. Cain have argued that the BWW&LH was never planned to be constructed, and was simply a vehicle to further Canadian Pacific's ambitions to enter into Kitchener, despite its agreement with the Grand Trunk a decade earlier.[8] In 1908, the GP&H and Preston and Berlin Street Railway were merged under the BWW&LH name, thereby giving Canadian Pacific a means to enter the Kitchener freight market, while ostensibly following the letter of its agreement with the Grand Trunk. In 1914, it was renamed to the Grand River Railway.

As CP's consolidation of lines with freight potential had been ongoing, the City of Berlin made a successful bid to take over the Berlin and Waterloo Street Railway and operate it as a public service, which was complete in 1906. This line, which operated primarily along King Street, largely served commercial areas, and was most suitable for passengers, but served a role similar to local bus services today, rather than a regional railway role similar to the Galt, Preston, and Hespeler Street Railway. In 1921, this separation of services increased as the Grand River Railway re-routed its trains to more fully follow the north–south freight line as a part of its switch from 600 V DC to 1500 V DC electrification in order to match the Lake Erie and Northern Railway, a move which prefigured their consolidation ten years later.[9] Throughout the rest of the 1920s, the Grand River Railway continued to shift to using shared freight track, a move which was hastened by municipal politicians working to force trains off of King Street in favour of car traffic.[10]

Canadian Pacific Electric Lines

In 1931, the Grand River Railway was consolidated with the Lake Erie and Northern Railway (LE&N), another Canadian Pacific Railway subsidiary, to form the Canadian Pacific Electric Lines (CPEL). Under unified CPEL management, the two services were advertised in tandem, and LE&N rolling stock received repairs at the Grand River Railway's Preston barn. During the same year, the Grand River Railway advertised hourly service on every day except Sunday between Galt, Hespeler, Preston, and Kitchener, from 5:50 a.m. to 11:45 p.m., and nine trains a day (except on Sundays) to Waterloo, reflecting Waterloo's lesser importance and smaller population at the time.[11] The Lake Erie and Northern, with its longer line and lower ridership, advertised primarily for summer excursion trips to Port Dover from the hot and crowded urban centres to the north, and during other parts of the year was largely sustained by its freight business.

Bus services

Bus services became increasingly common throughout the 1920s and 1930s as more roadways were paved, fuel prices decreased, and bus manufacturing began to scale up. Canadian Pacific followed these trends with the founding of its Canadian Pacific Transport Company, which was used to supplement and/or replace some train journeys.

Collisions with automobiles

Throughout the 1930s, collisions between interurban cars and private automobiles became increasingly common in urban parts of Kitchener-Waterloo, which was covered in detail by local newspapers like the Waterloo Chronicle alongside coverage of car-on-car collisions and pedestrians being struck and killed by automobiles. Around November 1937, the railway switched from whistles to horns at crossings, which were louder, leading to complaints from residents along the line and from the Waterloo town council.[12] These incidents only continued after the end of the Great Depression and the Second World War, when automobile ownership and traffic volumes climbed steadily. More reliable personal cars, as well as improved highway and automobile service infrastructure, made it easier to drive to unfamiliar cities whose street geometry (and railway operations) could prove dangerous.

- In January 1930, the earliest reported collision at Cedar Grove Avenue in Kitchener occurred when Joseph Zinger, while driving his automobile, crashed into a Grand River Railway interurban car.[13]

- on 1 August 1931, Charles Frank Houston died while pinned under his car following a collision with a Grand River Railway train at the Centreville crossing. A coroner's inquest later found that he had suffocated to death. The inquest absolved the train crew of blame, but "recommended the installation of visible warnings and signals at the crossing."[14]

- In July 1932, Leander Cressman of New Dundee was driving along Mill Street in Kitchener when his motor car collided with a Grand River Railway train, critically injuring him. He died later in hospital.[15]

- On 15 December 1937, Reginald E. Simpson, the local manager for the Sun Oil Company (later known as Sunoco), was driving his new automobile along Kent Avenue (the renamed Cedar Grove Avenue) when he was struck by a Grand River Railway car being driven by motorman H. C. Smith. Simpson was killed and his automobile was carried 198 feet (60 m).[16] His wife, Mary E. Simpson, claimed $86,155.23 in damages against the railway.[17]

- On 12 October 1946, Earl Hutchins, who was from Toronto, was driving through the Grand River Railway crossing in Centreville when his automobile was crushed by an interurban car. Similarly to the Simpson incident almost ten years earlier, Hutchins and his three passengers were killed.[18] His wife subsequently claimed $50,000 in damages against the railway.[19]

Overall service cuts

Amidst these events, regular passenger service to Waterloo was discontinued, after having previously been cut back to Allen Street from Erb Street. In early March 1938, it was reported that cars had only carried an average of five passengers per trip, with revenues to the company of $4.52 and expenses of $21.86 per day. The end of service was supported by the Waterloo town council, which deemed railway whistles and horns a nuisance.[20] Interurban cars were replaced by bus service, necessitating a linear transfer for passengers at Queen Street.[21] Ironically, passenger ridership in the overall system had yet to hit its peak, which would be nearly 1.7 million riders in 1940.[22]

Despite the overall success of the combined CPEL railway system, post-Second World War social trends began to cause a drop in ridership as regional travellers became increasingly likely to own and drive cars. The beginning of residential subdivision development stimulated population growth outside of the historic downtowns of Berlin (by then renamed to Kitchener), Galt, and Preston, and they began to fall victim to urban decay. In the years following the 1919 Canada Highways Act, which provided stimulus funding for highway development, it became more practical and desirable to travel intercity by car, and development and urban planning began to adjust to car-centric transportation with road widening, highway development, creation of low-density residential housing subdivisions, and demolition of many urban buildings to provide parking, creating an induced demand feedback loop that favoured further car-centric development, while many railway systems were discontinued or statically maintained, without significant expansion of track, upgrades to rolling stock, or sometimes even basic maintenance; the Kitchener and Waterloo Street Railway, which had been put under the management of the Kitchener Public Utilities Commission, was rendered disabled even before its planned shutdown due to damage to the overhead electrical wires which was not repaired.

In 1946, the combined Canadian Pacific Electric Lines system had a continuous 75.61-mile (121.68 km) mainline, while carrying 1.5 million passengers and over half a million tons of freight.[23] This represented a decline in passenger traffic of almost 200,000 riders per year compared to the peak in 1940. Meanwhile, Canadian Pacific Transport Company bus service was extended through Kitchener, and train and bus service began to alternate hourly. This followed a general trend, as train service was replaced with bus service on many railways, creating a downward spiral as ridership declined and train journeys with low ridership were cut or replaced with bus service.[24]

It was around this time that Canadian Pacific began to plan for total abandonment of passenger services along the line, even as freight carloads and profitability increased. In its first bid to discontinue service in 1950, Canadian Pacific's application was denied by Canada's Board of Transport Commissioners, but an allowance was made for Canadian Pacific to modify service as necessary to maintain profitability of passenger trips; as a direct result, Canadian Pacific discontinued nighttime passenger service altogether while simultaneously increasing fares, making railway journeys even less attractive to passengers.[25] Passenger rail advocates at the time warned that these service cuts would eventually lead to complete abandonment, and protested to bodies such as the Kitchener City Council.[26] Despite the cuts, passenger rail service continued until 23 April 1955, when it was replaced by bus service under the Canadian Pacific Transport Company. Bus service operations for Preston were sold to Canada Coach Lines Limited later that year, but Galt-to-Kitchener operations continued under the Canadian Pacific umbrella until 1 October 1961, when freight service was dieselized and assumed by the parent CPR.

Shifting industrial base

By the 1960s, Kitchener's industrial base began to shift to the suburbs. Manufacturing in Canada had begun to suffer due to numerous economic factors, and 19th century-style downtown factories, which were often rail-served, were declining and being phased out in favour of decentralized systems of suburban factories which were served by both trucks and rail, or in some cases wholly relied on the trucking industry. In a turbulent strike at the Kaufman Rubber Company in downtown Kitchener in 1960, coal deliveries to the factory via an industrial spur on Victoria Street became a point of conflict, as picketers tried to prevent Grand River Railway trains from entering the factory yard. Train crews refused to cross the United Rubber Workers' picket line, so the coal train was driven by company officials, including William D. Thompson, the general manager of the railway, and escorted by the Kitchener Police. The picket line was broken and three strikers were charged with violation of the Railway Act.[27] Within several years, footwear production for the company had shifted to Quebec after the acquisition of several smaller companies, and in 2000, the company (by then rebranded to Kaufman Footwear) declared bankruptcy.[28]

Plan No. 1251

This shift to the suburbs spurred the most extensive modification ever made to the railway's right of way. It was internally referred to as Plan No. 1251, which called for the southwest Kitchener portion of the line to be relocated from King Street to the newly built Industrial Park (today's Parkway and Trillium Industrial Park areas), cementing the shift from passengers to freight, and coinciding with the dieselization of its freight operations. The previous right-of-way along King Street had served early 20th century suburban residential areas like Kingsdale, and villages-turned-suburbs like Centreville; in contrast, the rail line's new location primarily served a new industrial park built on farm fields to the north of the former industrial village of German Mills, which had been served by the Canadian National Railway, Canadian Pacific's primary competitor. This industrial park would only later be joined by the residential and commercial area that grew up around Fairview Park Mall, which was built in 1965 as one of Kitchener's first suburban shopping malls. This shift allowed for the construction of Highway 8 as a separate-but-overlapping roadway (rather than simply a designation for King Street), obliterating much of the area's former rail infrastructure from Kitchener to Preston, and cementing the shift to an autocentric built environment. The seeds had been sown decades before, as municipal officials, who controlled the municipal right-of-way used for railway street running, began in the 1920s to deny the Grand River Railway's applications for renewal of their rail line's leases, forcing the railway into costly track relocations, which gradually forced the rail line further to the west of Kitchener's downtown, making it less convenient for passengers, and creating more room for the auto traffic which would prove to further interfere with railway operations.[10]

Passenger service

The Grand River Railway's passenger services were an evolution from earlier streetcar services. Mainline service was half-hourly since the start of the Galt and Preston Street Railway, and the Hespeler branch also received half-hourly evening service in 1920.[29]

Rolling stock

In the rail transport industry, the term rolling stock refers to easily moveable assets owned by railways, usually rail cars, which could be either self-propelled or hauled by a dedicated locomotive.

In 1921, with the switch to 1500 V operation and integration of the Grand River Railway and Lake Erie and Northern Railway rolling stock, the Grand River Railway used even numbers for its rolling stock, while the Lake Erie and Northern Railway used odd numbers.[30]

Locomotives

| Number | Manufacturer | Cab type | Built | Retired | Fate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRR 222 | Box | 1904 | Rebuilt in 1921 for 1500 V service.[31][30] | |||

| GRR 224 | Baldwin-Westinghouse | Steeple | 1907 | Rebuilt in 1921 for 1500 V service.[31] | ||

| GRR 226 | Preston Car Company | 1904 | Steel freight motor configured for multiple-unit service.[30] | |||

| GRR 228 | Preston Car Company | Steeple | 1921 | 1961 or later | Scrapped | Used along with LE&N 337 to haul the last ever passenger trip on Grand River Railway tracks on 30 September 1961, which used a number of CPR coaches as all interurban cars had already been disposed of.[32] After dieselization of the line, it was sold to the Iowa Terminal Railroad in July 1963. It was assigned a number as Iowa Terminal Railroad 82, but was never used or repainted from its previous colour scheme, and was eventually scrapped in 1968.[33] |

| GRR 230 | Baldwin-Westinghouse | Steeple | August 1930 | August 1971 | Preserved | Originally Salt Lake and Utah Railroad 106. Acquired by the CPEL in July 1946 after the SL&U shut down. Put into service as GRR 230. Rebuilt from 63 to 82 tons in 1953. Sold to the Cornwall Street Railway in November 1962 and was renumbered CSR 17. Transferred to CN Rail in 1971. Retired in August 1971 and preserved in Cornwall, Ontario.[34][35] Put on public display in August 1981. Serial number BLW 61456 |

Passenger, combine, and express cars

Most of the Grand River Railway's passenger rolling stock was built locally by the Preston Car Company.[36] The Preston Car Company was a specialized small manufacturer which focused almost "exclusively [on] building passenger equipment."[37] It manufactured cars for interurban railways throughout North America, as well as passenger coaches for some steam railways. The Preston plant closed in 1922,[37] however, and the railway turned to other manufacturers. In 1947, it commissioned Grand River Railway Car No. 626, a combination passenger and baggage motor car which seated eighteen passengers and was powered by four 125-hp Westinghouse motors, from National Steel Car of Hamilton, Ontario.[38] This was the last interurban railway car ever manufactured in Canada. In its short service life, it became the regular car on the run between Kitchener-Waterloo and the Galt intercity CPR station.[38] It was used for at least one of the excursion trips by railway enthusiasts which occurred after the end of regular revenue service,[38] and was planned to be converted into a maintenance of way car or to be sold. With neither of these possibilities materializing, it was scrapped at Preston on 21 May 1957.[38]

| Number | Type | Manufacturer | Built | Retired | Fate | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GRR 21 | Passenger | Ottawa Car Company | 1907 | before 1929 | Scrapped | 64-seat wooden car which was originally Preston and Berlin Street Railway 21. It was inherited by the Grand River Railway. The motor from the car was sold prior to 1929 and it was scrapped at Preston in 1935.[30] |

| GRR 31 | Passenger | Ottawa Car Company | 1907 | before 1929 | Scrapped | 64-seat wooden car which was inherited from the GP&H/P&B. The motor from the car was sold prior to 1929 and it was scrapped at Preston in 1935.[30] |

| GRR 622 | Express/baggage | Preston Car Company | 1921 | Steel express/baggage car designed for multiple-unit operation with passenger cars. Part of the 1921 order.[31] | ||

| GRR 624 | Combine | Preston Car Company | N/A | 34-seat steel combine car. The rebuilt and renumbered GRR 866.[31] | ||

| GRR 626 | Combine | National Steel Car | 1947 | Scrapped | The last interurban car built in Canada.[37] Scrapped on 21 May 1957.[38] | |

| GRR 824 | Passenger | Ottawa Car Company | 1910 | An inherited GP&H/P&B street railway wooden car which was rebuilt for 1500 V and electric multiple unit operation.[31] Rebuilt in 1923.[30] It disappears from the roster within ten years after this.[39] | ||

| GRR 826 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1911 or 1912[30] | Originally Preston and Berlin Street Railway 205. A 64-seat wooden passenger car.[30] Originally built for 600 V operation, then rebuilt for 1500 V and electric multiple unit operation.[31][40] | ||

| GRR 828 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1911 or 1912[30] | Originally Preston and Berlin Street Railway 215. A 64-seat wooden passenger car.[30] Rebuilt for 1500 V and electric multiple unit operation.[31] | ||

| GRR 842 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | 64-seat steel passenger car.[30] Part of the 1921 order.[31] | ||

| GRR 844 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | 64-seat steel passenger car.[30] Part of the 1921 order.[31] | ||

| GRR 846 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | 68-seat steel passenger car.[30] Part of the 1921 order.[31] | ||

| GRR 848 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | 1955 | Scrapped | 68-seat steel passenger car.[30] Part of the 1921 order.[31][41] |

| GRR 862 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | 1955–56 | Scrapped | 68-seat steel passenger car.[30] Part of the 1921 order. Overhauled at the CPR Angus Shops in Montreal in 1947. Scrapped at Preston in 1956.[42] |

| GRR 864 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | Scrapped | 68-seat steel passenger car.[30] | |

| GRR 866 | Passenger | Preston Car Company | 1921 | mid 1930s | Rebuilt | 68-seat steel passenger car.[30] Part of the 1921 order. Severely damaged by fire at one end in August 1933. Rebuilt as a baggage/express/passenger combine car in 1937 and renumbered as GRR 624.[31] |

Infrastructure

Trackage

Throughout its existence, the Grand River Railway's infrastructure changed to reflect the priorities and prosperity of its owners. Its complex track network included the constituent railways it had been formed from, as well as related, but separate, railways such as the Kitchener and Waterloo Street Railway. As the system aged, its physical infrastructure came to reflect an increasing emphasis on freight, as well as the capacity to carry heavier trains. Lighter rails which were more suitable for single passenger cars than freight trains were gradually replaced. For example, the very light 56-lb. rails on the Hespeler branch line were replaced with 65-lb. rails in the early 1910s,[43] and most of the mainline between Preston and Kitchener was relaid with 85-lb. rails in 1918.[44] In comparison, Canadian Pacific began in 1921 to generally replace the 85-lb. rails on the lines it directly maintained with 100-lb. rails, and some American railways started using rails as heavy as 130 lbs. Maintenance cost savings, safety, and the ability to use heavier locomotives were cited as major reasons for the mainline railways to use heavier rails.[45]

Despite its success during its heyday of the 1910s–20s, the Grand River Railway primarily represented a consolidation and modernization of existing railway infrastructure and trackage, and little expansion occurred. The most significant proposed expansion of trackage was a northwestern extension of the mainline from Waterloo. Had it been built, the extended line would have curved to the west through Erbsville, then north through Heidelberg, west again through St. Clements and Crosshill, and finally north again to Linwood to terminate at a junction with the CPR-owned Guelph and Goderich Railway, giving the Grand River Railway a second interchange point with the east–west Canadian Pacific lines in addition to the one with the mainline through Galt.[46][47] The extended line would have run entirely to the west of the then-Grand Trunk-operated Waterloo Junction Railway to Elmira through St. Jacobs, and would have passed through a number of villages which did not have rail service.

Stations

Emerging as it did from late-19th century street railways, the Grand River Railway system relied on simple trackside shelters for passengers and short industrial spurs for freight service, while also utilizing several purpose-built stations. As street running sections of track were gradually relocated, the emphasis on stations increased.

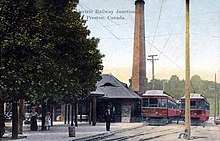

One of the most significant stations was Preston Junction, which sat near the middle of the line and which was located at the junction with the Hespeler branch that ran along the east side of the Speed River. Preston Junction had been an operations centre since the construction of the Preston and Berlin Street Railway in 1904, hosting the steam boilers that powered its electrification system, as well as its car barns, while also functioning as a passenger transfer point between it and the Galt, Preston and Hespeler Street Railway. The passenger station was constructed in 1905.[48] Under the consolidated Grand River Railway, Preston Junction continued to be an important station until the end of service.[7]

With interurban trains banished from King Street in Kitchener after 1919, a basic wooden station was built in 1921 near the railway crossing at Queen Street,[44] just outside of downtown to the southwest of the old Schneider family homestead. While a distance away from Kitchener's main corridor of King Street, it was located in a then-rapidly-growing suburban neighbourhood dominated by St. Mary's General Hospital, which opened in 1924. This created a direct passenger rail connection between the St. Mary's area and the Freeport Sanitorium, which opened in 1916.[49] The Queen Street station building was replaced by a "new and attractive"[50] brick building in November 1943, corresponding to a heavy increase in passenger traffic during the Second World War,[50] and coming several years after the discontinuance of service to Waterloo, which turned Kitchener Queen Street into a terminal station.[51]

Legacy

Much of the Grand River Railway's track continued to function as freight track for decades after passenger service was discontinued, but significant sections were removed in the 1980s, including the Hespeler branch, of which some portions are now the Mill Run Trail. Urban sections in Kitchener-Waterloo were largely also dismantled in the 1980s and replaced by the Iron Horse Trail in 1997, which features a number of plaques commemorating Kitchener's railway and industrial heritage. Perhaps most decisively, the junction that joined the GRNR and LE&N at Main Street in downtown Galt was also removed along with the LE&N track leading south to Paris, severing the original branch line laid down by the Great Western Railway in 1855, and ending rail traffic between the north and south halves of the Grand River valley.

A remnant of the Grand River Railway mainline, designated as the CP Waterloo Subdivision, remains an active rail corridor. From the Canadian Pacific mainline in the south (in the form of the Galt Subdivision), the line passes north through Galt and Preston, crossing the Speed River along approximately the same route as the original Grand River Railway. North of the river, there is an industrial spur to reach a Toyota automobile factory. The line then continues along its historic path, crossing the Grand River. It eventually deviates from the historic route at Centreville, curving to the west and following the 1963 rerouting through the Parkway industrial area. After curving to the north again, it terminates, joining with the CN Huron Park Spur at an interchange yard which is overlooked by the Block Line Ion light rail station.

The Grand River is also referenced in the name of Grand River Transit, which was formed in 2000 through a merger of Kitchener Transit and Cambridge Transit. It provides regional transit connections between many areas once served by the Grand River Railway.

Starting in the 1990s, planners and local government officials began to revisit the idea of a rapid transit system in the region. This culminated in the Ion rapid transit light rail system which opened to the public on 21 June 2019.[52] Ironically, this system (ION Stage 1) does not include either Galt or Preston, the original hubs for regional rail, and is instead centred on Kitchener-Waterloo. It does, however, use a similar right of way in some areas as the Grand River Railway, such as along Caroline Street in Waterloo. Ion Stage 2, which as of 2019 is still in the public consultation phase, would once again provide a passenger rail connection between Galt, Preston, and Berlin (Kitchener).[53][54]

See also

References

Citations

- "Grand River Valley". Retrieved 20 August 2019.

- http://www.walterbeantrail.ca/prestonberlin.htm

- Cain 1972, p. 9.

- Bean, Bill (24 October 2014). "LRT began in Galt and Preston in 1894". Waterloo Region Record. Retrieved 4 July 2019.

- Cain 1972, p. 14.

- Cain 1972, p. 15.

- Miller, William E. (19 July 2004). "PRESTON & BERLIN STREET RAILWAY COMPANY LIMITED PRESTON & BERLIN RAILWAY COMPANY LIMITED". Electric Lines in Southern Ontario. Trainweb. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- Cain 1972, p. 26.

- "CAMBRIDGE AND ITS INFLUENCE ON WATERLOO REGION'S LIGHT RAIL TRANSIT". Waterloo Region. Waterloo Region. 19 January 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- Cain 1972, p. 40.

- "Canadian Interurban Electric Railroads - 1930's - 1940's Grand River Railway Lake Erie & Northern Railway". 14 June 2011. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- "CAN'T CUT OUT HORN". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 81, no. 89. 5 November 1937. p. 3 – via Waterloo Public Library.

The horn which recently replaced the whistle on Grand River Railway radial cars cannot be toned down or removed, the town is informed in a letter from the Company. Residents along the railway have complained of the new horn as a nuisance, disturbing their sleep.

- "MOTOR CAR HIT BY RADIAL CAR". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 44, no. 3. 16 January 1930. p. 1 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "SUFFOCATION CAUSED DEATH OF HOUSTON". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 45, no. 34. 20 August 1931. p. 1 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "NEW DUNDEE MAN KILLED AT CROSSING". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 46, no. 27. 7 July 1932. p. 1 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "Action for Damages As Result of Death Reginald Simpson". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 82, no. 17. 1 March 1938. p. 8 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "Claim $86,155.23 Damages Against Grand River Ry". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 82, no. 27. 5 April 1938. p. 3 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "Four Persons Killed In Crossing Crash Near Kitchener". Ottawa Journal. 14 October 1946. p. 1.

- "Railways Asked $50,000 Damages". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 90, no. 2. 10 January 1947. p. 8 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "Grand River Ry. Stops Passenger Service to Town". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 82, no. 20. 11 March 1938. p. 1 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- Cain 1972, p. 28.

- Cain 1972, p. 46.

- "'Electrics' still popular mode". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 132nd Year, no. 24. 17 June 1987. p. 5 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- Cain 1972, p. 51.

- Cain 1972, p. 29.

- "Asks Retention of Grand Railway". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 93, no. 34. 25 August 1950. p. 1 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "Superior Box Company Closed By Strike". The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 104. 4 August 1960. p. 1 – via Waterloo Public Library.

- "Accession GA148 - Kaufman Footwear fonds". University of Waterloo. Retrieved 12 February 2021.

- "INCREASED SERVICE ON G.R.R." The Waterloo Chronicle. Vol. 65, no. 52. 23 December 1920. p. 11 – via Waterloo Public Library.

The Grand River Railway is running a half hour service from 4.50 to 7.20 o'clock p.m. daily.

- "ROSTER OF EQUIPMENT OF THE GRAND RIVER RAILWAY, LAKE ERIE & NORTHERN RAILWAY AND PREDECESSOR LINES". UCRS Bulletin. No. 16. Upper Canada Railway Society. April 1944. Retrieved 25 February 2021 – via CNR-in-Ontario.com.

- Miller, William E. (13 October 2009). "Grand River Railway". Electric Lines in Southern Ontario. Trainweb. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- Sandusky 2010.

- Miller, William E. "LE&N 337 & GRR 228". Electric Lines in Southern Ontario. Trainweb. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Preserved Ontario" (PDF). Bytown Railway Society. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- Weir, Laurie (5 February 2021). "Railway Museum of Eastern Ontario receives locomotive donation from Cornwall". Toronto.com. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- "Grand River Railway". Canada-Rail.com. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Merrilees 1963.

- "A TRIBUTE TO THE LAST ELECTRIC INTERURBAN CAR BUILT IN CANADA: GRAND RIVER RAILWAY 626". Trainweb.org. Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Mills 1977, p. 18.

- Sandusky 2010, p. 141.

- County of Brant Public Library Digital Collections. "Grand River Railway 848 Departs from Brantford". Retrieved 24 February 2021 – via OurOntario.ca.

- Sandusky 2010, p. 144.

- Mills 1977, p. 10.

- Mills 1977, p. 15.

- "Heavier Rails for Heavy Traffic". Railway Age. Vol. 85, no. 1. Simmons-Boardman Publishing. 7 July 1928. pp. 209–212.

- "WILL DISCUSS MANY TOPICS: General Meeting of Board of Trade Has Big Program". The Waterloo Chronicle–Telegraph. Vol. 63, no. 34. 21 August 1919. p. 9.

- "THE WELLESLEY EXTENSION". The Waterloo Chronicle–Telegraph. Vol. 63, no. 35. 28 August 1919. p. 2.

- Breithaupt 1917, p. 20.

- Flanagan, Ryan (22 June 2016). "Grand River Hospital's Freeport campus marks 100-year milestone". CTV News. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- Mills 1977, p. 21.

- Mills 1977, p. 20.

- Weidner, Johanna (8 May 2019). "Ion launch date set for June 21". Waterloo Region Record. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- Sharkey, Jackie (8 February 2017). "There's still wiggle room in the Region of Waterloo's LRT plans for Cambridge". CBC. CBC. Retrieved 10 March 2017.

- "Stage 2 ION". Region of Waterloo. Archived from the original on 22 April 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

Bibliography

- Breithaupt, W. H. (1917). "Waterloo County Railway History". Fifth Annual Report of the Waterloo Historical Society (PDF) (Report). Kitchener, Ontario: Waterloo Historical Society. pp. 14–23 – via Transport Sourcebook.

- Cain, Peter F. (6 May 1972). The Grand River Railway: A Study of a Canadian Intercity Electric Railroad (Thesis). Department of History, Waterloo Lutheran University.

- Merrilees, Andrew (1963). "THE RAILWAY ROLLING STOCK INDUSTRY IN CANADA: A History of 110 Years of Canadian Railway Car Building". Retrieved 12 November 2020.

- Mills, John M. (1977). "Chapter I: Galt, Preston & Hespeler Street Railway, Grand River Railway". Traction on The Grand: The Story of Electric Railways along Ontario's Grand River Valley. Railfare Enterprises. pp. 3–26. ISBN 0-919130-27-5.

- Sandusky, Robert J. (July–August 2010). Murphy, Peter; Smith, Douglas N. W. (eds.). "Canadian Pacific Electric Lines – History Overview" (PDF). Canadian Rail. Canadian Railroad Historical Association (537): 139–145. ISSN 0008-4875.

Further reading

- Hilton, George W.; Due, John Fitzgerald (1960). The Electric Interurban Railways in America. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-8047-4014-2. OCLC 237973.

- Kirkwood, M. W. (1939). Canadian Pacific Electric Lines.

- Roth, George; Clack, William (April 1987). Canadian Pacific's Electric Lines: Grand River Railway and the Lake Erie & Northern Railway. British Railway Modellers of North America. ISBN 0919487211.

External links

- Grand River Railway at Trainweb.org