Aging in dogs

Aging in dogs varies from breed to breed, and affects the dog's health and physical ability. As with humans, advanced years often bring changes in a dog's ability to hear, see, and move about easily. Skin condition, appetite, and energy levels often degrade with geriatric age. Medical conditions such as cancer, kidney failure, arthritis, dementia, and joint conditions, and other signs of old age may appear.

The aging profile of dogs varies according to their adult size (often determined by their breed): smaller dogs often live over 15–16 years (sometimes longer than 20 years), medium and large size dogs typically 10 to 20 years, and some giant dog breeds such as mastiffs, often only 7 to 8 years. The latter reach maturity at a slightly older age than smaller breeds—giant breeds becoming adult around two years old compared to the norm of around 13–15 months for other breeds.

Aging profile

They can be summarized into three types:

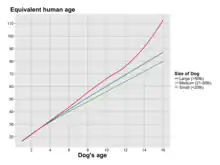

- Popular myth – It is popularly believed that one dog year equals seven human years.[2] This is considered to be inaccurate because dogs often reproduce at age 1 while humans almost never reproduce at age 7.

- One size fits all – A general rule of thumb is that the first year of a dog's life is equivalent to 15 human years, the second year equivalent to 9 human years, and each subsequent year about 5 human years.[3] So, a dog age 2 is equivalent to a human age 24, while a dog age 10 is equivalent to a human age 64. This is more accurate but still fails to allow for size/breed, which is a significant factor.

- Size- or breed-specific calculators – These try to factor in the size or breed as well. These are the most accurate types. They typically work either by expected adult weight or by categorizing the dog as "small", "medium", or "large".

No one formula for dog-to-human age conversion is scientifically agreed on, although within fairly close limits they show great similarities. Researchers suggest that dog age depends on DNA methylation which is an epigenetic process. Epigenetic changes occur nonlinear in dogs compared to human.[4]

Emotional maturity occurs, as with humans, over an extended period of time and in stages. As in other areas, development of giant breeds is slightly delayed compared to other breeds, and, as with humans, there is a difference between adulthood and full maturity (compare humans age 20 and age 40 for example). In all but large breeds, sociosexual interest arises around 6–9 months, becoming emotionally adult around 15–18 months and fully mature around 3–4 years, although as with humans learning and refinement continue thereafter.

According to the UC Davis Book of Dogs, small-breed dogs (such as small terriers) become geriatric at about 11 years; medium-breed dogs (such as larger spaniels) at 10 years; large-breed dogs (such as German Shepherd Dogs) at 8 years; and giant-breed dogs (such as Great Danes) at 7 years.[5]

Life expectancy by breed

Life expectancy usually varies within a range. For example, a Beagle (average life expectancy 13.3 years) usually lives to around 12–15 years, and a Scottish Terrier (average life expectancy 12 years) usually lives to around 10–16 years. The longest living verified dog so far is Bobi, a male purebred Rafeiro do Alentejo, who died at age 31 in 2023.

Two of the longest living dogs on record, "Bluey" and "Chilla", were Australian Cattle Dogs.[6] This has prompted a study of the longevity of the Australian Cattle Dog to examine if the breed might have exceptional longevity. The 100-dog survey yielded a mean longevity of 13.41 years with a standard deviation of 2.36 years.[7] The study concluded that while Australian Cattle Dogs are a healthy breed and do live on average almost a year longer than most dogs of other breeds in the same weight class, record ages such as Bluey's or Chilla's should be regarded as uncharacteristic exceptions rather than as indicators of common exceptional longevity for the entire breed.[7]

A random-bred dog (also known as a mongrel or a mutt) has an average life expectancy of 13.2 years in the Western world.

Some attempts[8][9] have been made to determine the causes for breed variation in life expectancy.

Sorted by breed or life expectancy

These data are from Michell (1999).[10] The total sample size for his study was about 3,000 dogs, but the sample size for each breed varied widely. For most breeds, the sample size was low. For a more comprehensive compilation of results of longevity surveys, search for breed specific tables.

Factors affecting life expectancy

Apart from breed, several factors influence life expectancy:

- Frequency of feeding — Researchers associated with the Dog Aging Project report that dogs that are fed just once daily are healthier on average than dogs fed more frequently. Dogs that received one meal per day had fewer disorders related to their dental, gastrointestinal, orthopedic, kidney, and urinary systems.[11][12]

- Diet — There are some disagreements regarding the ideal diet. Commonly, senior dogs are fed commercially manufactured Senior dog food diets. However, at least two dogs were listed as having died at 27 years old with non-traditional diets: a Border Collie who was fed a purely vegetarian diet,[13][14] and a bull terrier cross fed primarily kangaroo and emu meat.[15] They died only 2 years and 5 months younger than the second oldest reported dog, Bluey.

- Spaying and neutering — According to a study by the British Veterinary Association (author AR Michell is the president of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons), "Neutered females lived longest of dogs dying of all causes, though entire females lived longest of dogs dying of natural causes, with neutered males having the shortest lifespan in each category."[10] Neutering reduces or eliminates the risk of some causes of early death, for example pyometra in females, and testicular cancer in males, as well as indirect causes of early death such as accident and euthanasia (intact dogs roam and tend to be more aggressive), but there might increase the risk of death from other conditions (neutering in cited paper only showed an increase in the risk for prostate cancer but has not been repeated in subsequent papers) in males, and neutered males might have a higher rate for urinary tract cancers such as transitional cell carcinoma and prostatic adenocarcinoma.[16][17] Caution should be used when interpreting the results of these studies. This is especially important when you consider the frequency of transitional cell carcinoma and prostate carcinoma in a male dog versus the chance an intact male dog will succumb to death from roaming (hit by car or other injuries), benign hyperplasia of the prostate causing prostatic abscesses or inability to urinate (causing euthanasia if this does not resolve with therapy) or euthanasia due to fighting or aggression.

- Another study showed that spayed females live longer than intact females (0.8 years more on average) but, unlike the previous study, there were no differences between neutered and intact males. But both groups lived 0.4 years more than intact females.[18]

For more information, see Health effects of neutering.

A major study of dog longevity, which considered both natural and other factors affecting life expectancy, concluded that:

- "The mean age at death (all breeds, all causes) was 11 years and 1 month, but in dogs dying of natural causes it was 12 years and 8 months. Only 8 percent of dogs lived beyond 15, and 64 percent of dogs died of disease or were euthanized as a result of disease. Nearly 16 percent of deaths were attributed to cancer, twice as many as to heart disease. [...] In neutered males the importance of cancer as a cause of death was similar to heart disease. [...] The results also include breed differences in lifespan, susceptibility to cancer, road accidents and behavioral problems as a cause of euthanasia."[10]

Effects of aging

In general, dogs age in a manner similar to humans. Their bodies begin to develop problems that are less common at younger ages, they are more prone to serious or fatal conditions such as cancer, stroke, etc. They become less physically active and less mobile and may develop joint problems such as arthritis. They also become less able to handle change, including wide climatic or temperature variation, and may develop dietary or skin problems or go deaf. In some cases incontinence may develop and breathing difficulties may appear.

- "Aging begins at birth, but its manifestations are not noticeable for several years. The first sign of aging is a general decrease in activity level, including a tendency to sleep longer and more soundly, a waning of enthusiasm for long walks and games of catch, and a loss of interest in the goings on in the home."[19]

In studies of cognitive abilities in aging dogs, it has been shown that qualities such as problem-solving, boldness and playfulness tend to decline with age. However, in tasks involving high motivation and low physical demands, older dogs have learned to perform a new task just as well as younger ones. In old age dogs may develop dementia, which is associated with amyloid-beta, a misfolded protein that has been observed in both dogs and humans.[11]

The most common effects of aging are:[20]

- Loss of hearing

- Loss of vision (cataracts)

- Decreased activity, more sleeping, and reduced energy (in part due to reduced lung function)

- Weight gain (calorie needs can be 30–40% lower in older dogs)

- Weakening of immune system leading to infections

- Skin changes (thickening or darkening of skin, dryness leading to reduced elasticity, loss or whitening of hair)

- Change in feet and nails (thicker and more brittle nails makes trimming harder)

- Arthritis, dysplasia and other joint problems

- Loss of teeth

- Gastrointestinal upset (stomach lining, diseases of the pancreas, constipation)

- Weakness in muscles and bones

- Urinary issues (incontinence in both genders, and prostatitis/straining to urinate in males)

- Mammary cysts and tumors in females

- Dementia

- Heart murmurs

- Diabetes[21]

Importance of diet in aging

By changing the nutrition of a dog's diet as it ages, certain ailments and side effects of aging can be prevented or slowed.

Some important nutrients and ingredients in senior dog diets include:

- Good sources of protein[22] to meet higher protein requirements[23]

- Glucosamine[24] and chondroitin sulfate[24] to help maintain joint and bone health

- Omega-3 fatty acids[25] for joint and bone health as well as maintaining immune system health

- Calcium and phosphorus[26] for maintenance of bone structure

- Beet pulp[27] and flaxseed[28] for gastrointestinal health

- Fructooligosaccharides and mannanoligosaccharides work to improve the health of the gastrointestinal tract by increasing the number of "good" bacteria and decreasing the amount of "bad" bacteria[29]

- Appropriate levels of vitamin E and addition of L-carnitine to support brain and cognitive health[30]

- Dietary antioxidants such as vitamin E.[31]

References

- "How to Calculate Your Dog's Age".

- "How to Calculate Dog Years to Human Years". Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- "How to Calculate Dog Years to Human Years". Retrieved 2023-10-25.

- Wang, Tina; Ma, Jianzhu; Hogan, Andrew N.; Fong, Samson; Licon, Katherine; Tsui, Brian; Kreisberg, Jason F.; Adams, Peter D.; Carvunis, Anne-Ruxandra; Bannasch, Danika L.; Ostrander, Elaine A. (2020-07-02). "Quantitative Translation of Dog-to-Human Aging by Conserved Remodeling of the DNA Methylome". Cell Systems. 11 (2): 176–185.e6. doi:10.1016/j.cels.2020.06.006. ISSN 2405-4712. PMC 7484147. PMID 32619550.

- Siegal, Mordecai (Ed.; 1995). UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine Book of the Dogs; Chapter 5, "Geriatrics", by Aldrich, Janet. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-06-270136-3.

- World's oldest pooch dies, Beaver County Times, 13 March 1984. Retrieved 9 May 2011.

- Lee, P. (2011). Longevity of the Australian Cattle Dog: Results of a 100-Dog Survey. ACD Spotlight, Vol. 4, Issue 1, Spring 2011, 96–105. http://www.acdspotlight.com/

- McAloney, CA; Silverstein, KA; Modiano, JF; Bagchi, A (2014). "Polymorphisms within the Telomerase Reverse Transcriptase gene (TERT) in four breeds of dogs selected for difference in lifespan and cancer susceptibility". BMC Vet Res. 10: 20. doi:10.1186/1746-6148-10-20. PMC 3904191. PMID 24423165.

- Dog Aging Project

- Michell AR (November 1999). "Longevity of British breeds of dog and its relationships with sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease". Vet. Rec. 145 (22): 625–9. doi:10.1136/vr.145.22.625. PMID 10619607. S2CID 34557345.

- Ogden, Lesley Evans (27 July 2022). "Inside the brains of aging dogs". Knowable Magazine | Annual Reviews. doi:10.1146/knowable-072622-1. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

- Bray, Emily E.; Zheng, Zihan; Tolbert, M. Katherine; McCoy, Brianah M.; Consortium, Dog Aging Project; Kaeberlein, Matt; Kerr, Kathleen F. (22 January 2022). "Once-daily feeding is associated with better health in companion dogs: Results from the Dog Aging Project": 2021.11.08.467616. doi:10.1101/2021.11.08.467616. Retrieved 10 August 2022.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Vegetable-Eating Dog Lives to Ripe Old Age of 29; Also: Who is the Oldest Dog in the World; 1.8 Years Longer Archived February 5, 2016, at the Wayback Machine

- "Bramble oldest dog died yesterday". Archived from the original on 2013-01-03.

- Fickling, David (July 11, 2004). "'Oldest' dog heads for 27th birthday". World News. The Guardian. Retrieved November 30, 2013.

- Canine prostate carcinoma: epidemiological evidence of an increased risk in castrated dogs, Teske E, Naan EC, van Dijk EM, Van Garderen E, Schalken JA, Department of Clinical Sciences of Companion Animals, Utrecht University, The Netherlands.

- "A population study of neutering status as a risk factor for canine prostate cancer" Bryan JN, Keeler MR, Henry CJ, et al., Prostate. 2007 Aug 1;67(11):1174–81).

- O’Neill, D. G.; Church, D. B.; McGreevy, P. D.; Thomson, P. C.; Brodbelt, D. C. (2013). "Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England" (PDF). The Veterinary Journal. 198 (3): 638–43. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020. PMID 24206631.

- "Dog Owner's Guide: The older dog".

- PetPlace.com. "What to Expect as Your Dog Ages".

- PetPlace.com. "Questions About Senior Dogs".

- "Dietary Protein for Dogs and Cats - The Importance of Digestible Proteins". November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Churchill, Julia A (2015). "Nutrition for senior dogs: New tricks for feeding old dogs". Clinician's Brief.

- "Chondroitin Sulfate and Glucosamine Supplements in Osteoarthritis". Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Roush, James K.; Cross, Alan R.; Renberg, Walter C.; Dodd, Chadwick E.; Sixby, Kristin A.; Fritsch, Dale A.; Allen, Timothy A.; Jewell, Dennis E.; Richardson, Daniel C. (2010). "Evaluation of the effects of dietary supplementation with fish oil omega-3 fatty acids on weight bearing in dogs with osteoarthritis". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 236 (1): 67–73. doi:10.2460/javma.236.1.67. PMID 20043801.

- "Calcium Supplements". vca_corporate. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- "The Benefits of Beet Pulp in Pet Foods". www.peteducation.com. Retrieved 2017-11-22.

- "Common Pet Food Ingredients" (PDF). Skaer Veterinary Clinic. Retrieved November 22, 2017.

- Swanson, K.S.; Grieshop, C.M.; Flickinger, E.A.; Bauer, L.L.; Healy, HP.; Dawson K.A.; Merchen N.R.; Fahey G.G. Jr. (May 2002). "Supplemental Fructooligosaccharides, Mannanoligosaccharides Influence Immune Function, Ileal and Total Tract Nutrient Digestibilities, Microbial Populations and Concentrations of Protein Catabolites in the Large Bowel of Dogs". The Journal of Nutrition. 132 (5): 980–989. doi:10.1093/jn/132.5.980. PMID 11983825.

- Roudebush, Philip; Zicker, Steven C.; Cotman, Carl W.; Milgram, Norton W.; Muggenburg, Bruce A.; Head, Elizabeth (2005-09-01). "Nutritional management of brain aging in dogs". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 227 (5): 722–728. doi:10.2460/javma.2005.227.722. ISSN 0003-1488. PMID 16178393.

- Wander, R. C.; Hall, J. A.; Gradin, J. L.; Du, S. H.; Jewell, D. E (June 1997). "The ratio of dietary (n-6) to (n-3) fatty acids influences immune system function, eicosanoid metabolism, lipid peroxidation and vitamin E status in aged dogs". The Journal of Nutrition. 127 (6): 1198–1205. doi:10.1093/jn/127.6.1198. PMID 9187636.