Carcinosoma

Carcinosoma (meaning "crab body") is a genus of eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Carcinosoma are restricted to deposits of late Silurian (Late Llandovery to Early Pridoli) age. Classified as part of the family Carcinosomatidae, which the genus lends its name to, Carcinosoma contains seven species from North America and Great Britain.

| Carcinosoma Temporal range: Late Llandovery-Early Pridoli, | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of C. newlini, the telson is inaccurately reconstructed | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Carcinosomatoidea |

| Family: | †Carcinosomatidae |

| Genus: | †Carcinosoma Claypole, 1890 |

| Type species | |

| †Carcinosoma newlini (Claypole, 1890) | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

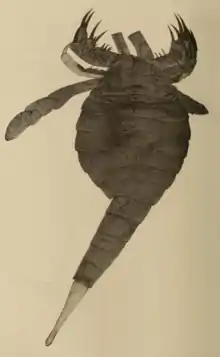

Carcinosomatid eurypterids had unusual proportions and features compared to other eurypterids, with a broad abdomen, thin and long tail and spined and forward-facing walking appendages. They were not as streamlined as other groups but had considerably more robust and well developed walking appendages. In Carcinosoma, these spined walking appendages are thought to have been used to create a trap to capture prey in. The telson (the posteriormost division of the body) of Carcinosoma appears to have possessed distinct segmentation, Carcinosoma is the only known eurypterid to possess this feature.

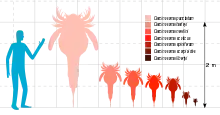

At 2.2 meters (7.2 ft) in length, the species C. punctatum is the largest carcinosomatoid eurypterid by far and is among the largest eurypterids overall, rivalling the large pterygotid eurypterids (such as Jaekelopterus) in size. Other species of the genus were considerably smaller, with most ranging from 70 centimeters (2.3 ft) to 100 centimeters (3.3 ft) in length.

Description

Carcinosoma was among the largest eurypterids, with isolated fossil remains consisting of a 12.7 centimeters (5.0 in) long metastoma (a plate overlaying the coxae of the first six appendages) of the species C. punctatum indicating a full length of 2.2 meters (7.2 ft). Fossil prosomal appendages (appendages attached to the head) referred to the species could possibly increase this estimate to an overall length of around 2.5 meters (8.2 ft).[1] This massive size makes C. punctatum the largest of all known carcinosomatoid eurypterids and it rivals the largest pterygotid eurypterids, such as the 2.5-meter (8.2 ft) long Jaekelopterus, in size.[1][2] Other species of Carcinosoma were smaller, most being in the range of 70 centimeters (2.3 ft) to 100 centimeters (3.3 ft) in length.[2]

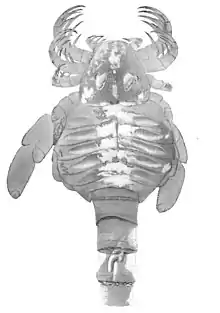

Perhaps the most recognizable features of Carcinosoma are its spined appendages and its broad and flattened mesosoma (the first six segments of its abdomen). Carcinosomatid eurypterids such as Carcinosoma had less streamlined bodies than those of some other groups, notably the highly streamlined pterygotid eurypterids. In contrast, the walking legs of the carcinosomatids were in general more robust and better developed.[3][4] Indeed, the walking legs (the second to fifth pair of appendages) were stout and strong and increased in size anteriorly, from the fifth to third pair of appendages, though the first pair of appendages were much shorter than the following pairs. As such, the second pair of walking legs were the longest. Each walking appendage possessed long and curved spines, often two such spines occurring per joint.[4] These spines are one of the defining features of the carcinosomatid family, along with that the swimming legs have slightly elongated and expanded seventh and eighth podomeres (leg segments).[3]

The body of Carcinosoma was somewhat oddly proportioned in comparison to other eurypterids, though similar to that of related carcinosomatids (particularly Eusarcana). The preabdomen (frontal part of the body) was broad and ovally shaped whilst the postabdomen (the posterior part of the body) was narrow and cylindrical. The prosoma (head) was subtriangular in shape with the small compound eyes placed at the front. The metasoma of Carcinosoma was covered in fine and elongated scales and was quite flat, a feature which separates the genus from Eusarcana where the metasoma was almost cylindrical.[4]

Color

A well-preserved specimen of C. newlini, specimen number 502 in the collections of the American Museum of Natural History (collected in the Kokomo Formation of Indiana), preserves the integument in enough detail to determine the coloration C. newlini would have possessed in life. By surveying the distribution of fossilized pigment cells and comparing them with those of modern scorpions, scientists were able to see the pattern and specific colors C. newlini would have possessed in life.[4]

Overall, the color was similar to that of modern scorpions and to that of another eurypterid which had been similarly studied, Megalograptus ohioensis. The dorsal side of the prosoma, mesosoma and the tergites (segments) of the metasoma were light brown while elongated scales alongside the exoskeleton were darker brown grading into black at the apex of the scales. Smaller scales alongside the edges of the metasomal tergites were also brown but contrasted against the lighter brown of the other integument. The operculum (the first and second abdominal segments) and the plates of the abdomen were brown but lighter than the tergites and their scales were, as with the other scales, darker than the surrounding integument.[4]

Black-tipped scales also occurred on the legs, where the general integument was dark brown. The spines of the walking legs were dark brown but black at their tips. The flattened scales on the swimming paddles also graded into black, though the paddle was otherwise brown. The coxae were light brown, with darker scales. The gnathobases ("tooth-plates" on the coxae used when feeding) were completely black, as were the telson (the posteriormost division of the body) whose color contrasted with the preceding and adjacent brown segment.[4]

Size

Carcinosoma ranged in size from 20 centimeters (7.9 in) to 2.2 meters (7.2 ft) in length, with the largest species by far being C. punctatum, known from the Ludlow epoch of England, and the smallest being C. libertyi, known from the Late Llandovery epoch of Canada. Though no other species came close to the size of C. punctatum, many species were moderately large, including C. harleyi from the Late Ludlow epoch of England at 100 centimeters (3.3 ft), C. newlini from the Early Pridoli epoch of the United States at 90 centimeters (3.0 ft), C. scoticus from the Llandovery epoch of Scotland at 75 centimeters (2.46 ft) and C. spiniferum from the Late Ludlow epoch of the United States at 70 centimeters (2.3 ft). The second smallest known species was C. scorpioides from the Wenlock epoch of Scotland at 38 centimeters (1.25 ft) in length.[2]

History of research

Carcinosoma was first described under the name Eurysoma (meaning "wide body", deriving from Greek εὐρύς, "wide",[5] and Latin soma, "body"[6]) by British American geologist and paleobotanist Edward Waller Claypole in 1890, who named the type species of the new genus E. newlini in honor of a C. E. Newlin who had collected the fossils. The Eurysoma specimens had been discovered in deposits of Early Pridoli age in the Kokomo Formation of Indiana alongside several other eurypterid specimens, all of which at the time were referred to Eurypterus lacustris (though Claypole noted in the same paper that this may have been done hastily). Later in the same year, Claypole discovered that the name Eurysoma was preoccupied and thus not available to be used for his genus of eurypterids.[4] Eurysoma had been named in 1831 for a genus of modern beetles and is today considered synonymous with the genus Brachygnathus.[7] Claypole replaced the name Eurysoma with the new name Carcinosoma.[4] Carcinosoma means "crab body" deriving from Latin cancer, "crab",[8] and soma, "body".[6]

In 1868, English geologist and paleontologist Henry Woodward named a new species of Eurypterus, E. scorpioides, based on fossils from Lanarkshire, Scotland. Woodward could easily distinguish the species from other genera present at the locality, such as Slimonia and Pterygotus.[9] Another species of Eurypterus, E. scoticus was named in 1899 by Scottish zoologist and paleontologist Malcolm Laurie based on fragmentary remains recovered in deposits of Llandovery age in Scotland.[10]

In 1912, American paleontologists John Mason Clarke and Rudolf Ruedemann noted that Carcinosoma was sufficiently similar to the related eurypterid Eusarcus to be designated as synonymous with it. As Eusarcus had been named in 1875, fifteen years earlier than Carcinosoma, its name had priority and replaced Carcinosoma. At this time, the combined genus of Eusarcus contained several species that are today seen as Carcinosoma, including C. newlini, C. scoticus and C. scorpioides, which Clarke and Ruedemann had referred to the genus on account of their similarities with C. newlini and species previously referred to Eusarcus.[11][12] In 1934, 59 years after it had been described, Eusarcus was recognized as a name preoccupied by a harvestman. The Norwegian geologist Leif Størmer proposed that the name of the taxon should be next oldest available and valid name for the genus, Carcinosoma. During the preparation for his paper on the issue, Størmer also discussed the situation with fellow Norwegian researcher Embrik Strand, who helped confirm that Carcinosoma was not preoccupied.[12]

Strand would subsequently propose the replacement name Eusarcana in 1942, despite the problem having been dealt with by Størmer, who he had been in contact with, eight years earlier. The reasons for proposing the name during the circumstances of the time remains unknown, but critique from contemporary researchers of Strand for his studies in systematics and an apparent desire to name as many taxa as possible may explain the situation somewhat. As it was seen as completely unnecessary at the time, Strand's Eusarcana was overlooked and not even mentioned in subsequent eurypterid studies.[12]

In 1961, American paleontologist Erik N. Kjellesvig-Waering classified Eurypterus punctatus (originally described as Pterygotus punctatus by English paleontologist and prominent eurypterid researcher John William Salter in 1859) as Carcinosoma punctatum and named a new species C. harleyi based on fossils from the Ludlow epoch of the Welsh Borderland. Kjellesvig-Waering could differentiate C. harleyi from C. punctatum based on C. harleyi lacking serrations on the eighth podomere of the swimming leg and the serrations of the ninth podomere being less developed.[3]

C. punctatum was diagnosed by Kjellesvig-Waering in 1961 based on the considerably pronounced serrations of the distal parts of its swimming leg, but the diagnosis is only valid for the lectotype specimen of the species, BGS GSM89435 (compromising the distal parts of a swimming leg discovered in deposits of Middle Ludlow age in the Mocktree Shale of Leintwardine in Herefordshire, England), and four other specimens from the same locality (BMNH 39389, BMNH In. 43804, BGS GSM89561 and GSM89568). Due to a close resemblance of the swimming legs, C. punctatum is assumed to have been similar in appearance to C. newlini. C. punctatum can be distinguished from C. newlini by the serration along the margin of the distal podomeres of C. punctatum being more pronounced.[3]

C. harleyi, from the Late Ludlow epoch, was described mainly based on specimens previously known (some having been reported by Salter as early as 1859) but previously referred to Eurypterus punctatus. Recognized by Kjellesvig-Waering as distinct, the species is named in honor of John Harley, one of the earliest collectors of eurypterid fossils in the region. Noted as moderately large in size by Kjellesvig-Waering, the holotype specimen of C. harleyi (No. 89434 in the collection of the Geological Survey and Museum in London) is a fragment of a swimming leg measuring 5 centimeters (2.0 in) in length. The nearly complete lack of serrations in the joints of C. harleyi makes the species very distinct from C. punctatum and other species of Carcinosoma.[1]

In 1964, both C. punctatum and C. harleyi were still recognized as part of Carcinosoma following an emended diagnosis of the genus by Kjellesvig-Waering and American paleontologist Kenneth Edward Caster, though C. harleyi was only tentatively recognized. Further species recognized at the time were C. libertyi and C. logani (both from Ontario, Canada; C. logani was later found to be a crustacean and not a eurypterid at all), C. spiniferum (from New York, United States), C. newlini (from Indiana, United States), C. scorpioides and C. scoticus (both from Scotland). Out of these species, only C. newlini and C. scorpioides preserve the swimming legs, where the diagnostic characters of the genus are, which makes the assignment of the other species to Carcinosoma less secure.[3] Kjellesvig-Waering and Caster also recognized Eusarcus and Carcinosoma to be distinct genera when revising the superfamily Carcinosomatoidea, and coined the replacement name Paracarcinosoma to designate the species previously assigned to Eusarcus. E. scorpionis was designated the type species. Caster and Kjellesvig-Waering made no mention of Embrik Strand or Eusarcana, and they were likely not aware of the existence of the previous name. In 2012, American paleontologists Jason A. Dunlop and James Lamsdell designated Paracarcinosoma as a junior synonym of Eusarcana per the taxonomic laws of priority.[12]

Classification

Carcinosoma is classified as part of the family Carcinosomatidae, a family within the superfamily Carcinosomatoidea, alongside the genera Eusarcana, Eocarcinosoma, Rhinocarcinosoma[13] and possibly Holmipterus.[14] The cladogram below is adapted from a larger cladogram (simplified to only display the Carcinosomatoidea) in a 2007 study by eurypterid researcher O. Erik Tetlie, in turn based on results from various phylogenetic analyses on eurypterids conducted between 2004 and 2007.[15] The second cladogram below is simplified from a study by Lamsdell et al. (2015).[14]

|

Tetlie (2007)

|

Lamsdell et al. (2015)

|

Paleobiology

The walking legs of Carcinosoma were turned forward, which also directed the large spines on the appendages forward. In C. newlini, these flat and forward-facing legs are thought to have been used to create a trap to capture prey in. The strong structures seen in C. newlini are not reflected in other carcinosomatids. For instance, the appendages of Eusarcana were much more weakly developed and would not have served as an effective weapon. Eusarcana is more likely to have relied on its telson, taking the shape of a sharp and curved stinger similar to that of scorpions and potentially capable of injecting venom.[4]

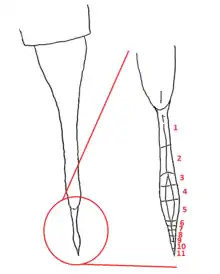

Instead of taking the shape of a scorpion-like stinger, the telson of Carcinosoma was slightly flattened and expanded anteriorly. The telsons of most eurypterids ends in a spike but the telson of Carcinosoma ended in a small and expanded structure with distinct segmentation, fossils preserving ten segments (though a small portion of the structure is not preserved, making more segments possible), otherwise not definitely reported from a eurypterid. The only other eurypterid from which a segmented structure occurring as part of the telson has been reported in is the slimonid Salteropterus abbreviatus. With such segmentation reported from two separate eurypterid genera, it is possible that the eurypterid telson is actually developed from a formerly normal abdominal segment and is thus not homologous to the telson of other arthropod groups.[4] Further studies of Salteropterus has since revealed that the perceived "segmentation" of its "post-telson" was misinterpreted ornamentation of an elongated and unusually shaped telson and not actual segmentation, making the segmentation of Carcinosoma unique.[16]

Paleoecology

As the opisthosoma of Carcinosoma wasn't as streamlined as that of more active eurypterids and on account of its unique telson morphology, it is believed that Carcinosoma was not a very active swimmer. It is unlikely to have been well adapted to a completely nektonic (actively swimming) lifestyle and is more likely to have been nektobenthic (swimming near the bottom).[3] The flat metasoma of Carcinosoma was probably used as at least partially as aid when swimming, suggested by the pretelson being slightly expanded in comparison to other eurypterids.[4]

As a considerable majority of described eurypterid species are known from the Silurian, particularly the late Silurian, researchers have concluded that the group peaked in diversity and number during this time.[17] Complex eurypterid faunas, compromising several different species in different ecological roles, are typical of the period.[15] These faunas were typically dominated by one or more particular eurypterid families, the dominant groups depending on the environment and location. Three such types of eurypterid faunas have been documented from the late Silurian, out of which a Carcinosomatidae-Pterygotidae fauna is the most marine type.[1]

All known examples of Carcinosoma are known from marine beds, typically occurring with trilobites, starfish, bryozoans, brachiopods, linguloids and other marine animals. Carcinosoma also prominently occurs together with pterygotid eurypterids. In the fossil deposits of the Welsh Borderland, examples of Carcinosoma occur together with representatives of the pterygotid genera Erettopterus and Pterygotus over a period of millions of years (though other eurypterids, such as Salteropterus, Dolichopterus, Hughmilleria, Eurypterus, Marsupipterus, Mixopterus, Parahughmilleria, Slimonia, Tarsopterella and Stylonurus are also present in lesser numbers).[1]

Other types of late Silurian eurypterid faunas include one dominated by the Eurypteridae. When genera such as Erieopterus or Eurypterus occur in great numbers other genera and families are more rare, though groups such as dolichopterids, carcinosomatids and pterygotids tend to occur in small numbers. The environments with such faunas appear to be quieter waters such as lagoons, estuaries and bays. The third and final recognized type of fauna is one dominated by hughmilleriids and stylonurids, generally alongside sandy bottoms and with few other associated fossils. The environments inhabited by this third fauna was likely less marine than the others, possibly representing the more brackish parts of bays and estuaries.[1]

References

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1961). "The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland". Journal of Paleontology. 35 (4): 789–835. JSTOR 1301214.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters. 6 (2): 265–9. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. PMC 2865068. PMID 19828493. Supplementary information. Archived from the original on 2018-02-28. Retrieved 2018-08-19.

- Gladwell, David Jeremy (2005). "The biota of Upper Silurian submarine channel deposits, Welsh Borderland". Theses, Leicester University Dept. Of Geology.

- Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1958). "Some Previously Unknown Morphological Structures of Carcinosoma newlini (Claypole)". Journal of Paleontology. 32 (2): 295–303. JSTOR 1300736.

- John R. Nudds; Paul Selden (2008). Fossil ecosystems of North America: a guide to the sites and their extraordinary biotas. Manson Publishing. pp. 74, 78–82. ISBN 978-1-84076-088-0.

- Meaning of soma at www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- "Eurysoma splendidum". Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Retrieved 17 September 2018.

- Meaning of cancer at www.dictionary.com. Retrieved 7 September 2018.

- Woodward, Henry (1868). "On some New Species of Crustacea from the Upper Silurian Rocks of Lanarkshire &c.; and further observations on the Structure of Pterygotus". Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society. 24 (1–2): 289–296. doi:10.1144/GSL.JGS.1868.024.01-02.36. ISSN 0370-291X. S2CID 128874377.

- O'Connell, Marjorie (1916). The Habitat of the Eurypterida. pp. 1–278.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Clarke, John Mason; Ruedemann, Rudolf (1912). The Eurypterida of New York. University of California Libraries. ISBN 978-1125460221.

- Dunlop, Jason A.; Lamsdell, James C. (2012). "Nomenclatural notes on the eurypterid family Carcinosomatidae". Zoosystematics and Evolution. 88 (1): 19–24. doi:10.1002/zoos.201200003. ISSN 1435-1935. S2CID 84224027.

- Dunlop, J. A.; Penney, D.; Jekel, D. (2018). "A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives" (PDF). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern.

- Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (September 1, 2015). "The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 169. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. PMC 4556007. PMID 26324341.

- Tetlie OE (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- Tetlie, O. Erik (2006). "Eurypterida (Chelicerata) from the Welsh Borderlands, England". Geological Magazine. 143 (5): 723–735. Bibcode:2006GeoM..143..723T. doi:10.1017/S0016756806002536. ISSN 1469-5081. S2CID 83835591.

- O'Connell, Marjorie (1916). "The Habitat of the Eurypterida". The Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences. 11 (3): 1–278.