Caricature

A caricature is a rendered image showing the features of its subject in a simplified or exaggerated way through sketching, pencil strokes, or other artistic drawings (compare to: cartoon). Caricatures can be either insulting or complimentary, and can serve a political purpose, be drawn solely for entertainment, or for a combination of both. Caricatures of politicians are commonly used in newspapers and news magazines as political cartoons, while caricatures of movie stars are often found in entertainment magazines.

In literature, a caricature is a distorted representation of a person in a way that exaggerates some characteristics and oversimplifies others.[1]

Etymology

The term is derived for the Italian caricare—to charge or load. An early definition occurs in the English doctor Thomas Browne's Christian Morals, published posthumously in 1716.

Expose not thy self by four-footed manners unto monstrous draughts, and Caricatura representations.

with the footnote:

When Men's faces are drawn with resemblance to some other Animals, the Italians call it, to be drawn in Caricatura

Thus, the word "caricature" essentially means a "loaded portrait". Until the mid 19th century, it was commonly and mistakenly believed that the term shared the same root as the French 'charcuterie', likely owing to Parisian street artists using cured meats in their satirical portrayal of public figures.[2]

History

Some of the earliest caricatures are found in the works of Leonardo da Vinci, who actively sought people with deformities to use as models. The point was to offer an impression of the original which was more striking than a portrait.

Caricature took a road to its first successes in the closed aristocratic circles of France and Italy, where such portraits could be passed about for mutual enjoyment.

While the first book on caricature drawing to be published in England was Mary Darly's A Book of Caricaturas (c. 1762), the first known North American caricatures were drawn in 1759 during the battle for Quebec.[3] These caricatures were the work of Brig.-Gen. George Townshend whose caricatures of British General James Wolfe, depicted as "Deformed and crass and hideous" (Snell),[3] were drawn to amuse fellow officers.[3]

Elsewhere, two great practitioners of the art of caricature in 18th-century Britain were Thomas Rowlandson (1756–1827) and James Gillray (1757–1815). Rowlandson was more of an artist, and his work took its inspiration mostly from the public at large. Gillray was more concerned with the vicious visual satirisation of political life. They were, however, great friends and caroused together in the pubs of London.[5]

Published from 1868 to 1914, the London weekly magazine Vanity Fair became famous for its caricatures of famous people in society.[6] In a lecture titled The History and Art of Caricature, the British caricaturist Ted Harrison said that the caricaturist can choose to either mock or wound the subject with an effective caricature.[7] Drawing caricatures can simply be a form of entertainment and amusement – in which case gentle mockery is in order – or the art can be employed to make a serious social or political point. A caricaturist draws on (1) the natural characteristics of the subject (the big ears, long nose, etc.); (2) the acquired characteristics (stoop, scars, facial lines etc.); and (3) the vanities (choice of hair style, spectacles, clothes, expressions, and mannerisms).

Notable caricaturists

- Sir Max Beerbohm (1872–1956, British), created and published caricatures of the famous men of his own time and earlier. His style of single-figure caricatures in formalized groupings was established by 1896 and flourished until about 1930. His published works include Caricatures of Twenty-five Gentlemen (1896), The Poets' Corner (1904), and Rossetti and His Circle (1922). He published widely in fashionable magazines of the time, and his works were exhibited regularly in London at the Carfax Gallery (1901–18) and Leicester Galleries (1911–57).

- George Cruikshank (1792–1878, British) created political prints that attacked the royal family and leading politicians. He went on to create social caricatures of British life for popular publications such as The Comic Almanack (1835–1853) and Omnibus (1842). Cruikshanks' New Union Club of 1819 is notable in the context of slavery.[8] He also earned fame as a book illustrator for Charles Dickens and many other authors.

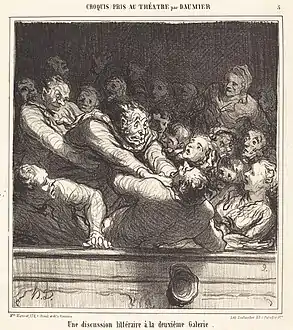

- Honoré Daumier (1808–1879, French) created over 4,000 lithographs, most of them caricatures on political, social, and everyday themes. They were published in the daily French newspapers (Le Charivari, La Caricature etc.)

- Mort Drucker (1929-2020, American) joined Mad in 1957 and became well known for his parodies of movie satires. He combined a comic strip style with caricature likenesses of film actors for Mad, and he also contributed covers to Time. He has been recognized for his work with the National Cartoonists Society Special Features Award for 1985, 1986, 1987, and 1988, and their Reuben Award for 1987.

- Alex Gard (1900–1948, Russian) created more than 700 caricatures of show business celebrities and other notables for the walls of Sardi's Restaurant in the theater district of New York City: the first artist to do so. Today the images are part of the Billy Rose Theatre Collection of The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.[9]

- Al Hirschfeld (1903–2003, American) was best known for his simple black and white renditions of celebrities and Broadway stars which used flowing contour lines over heavy rendering. He was also known for depicting a variety of other famous people, from politicians, musicians, singers and even television stars like the cast of Star Trek: The Next Generation. He was even commissioned by the United States Postal Service to provide art for U.S. stamps. Permanent collections of Hirschfeld's work appear at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, and he boasts a star on the St. Louis Walk of Fame.

- Sebastian Krüger (1963, German) is known for his grotesque, yet hyper-realistic distortions of the facial features of celebrities, which he renders primarily in acrylic paint, and for which he has won praise from The Times. He is well known for his lifelike depictions of The Rolling Stones, in particular, Keith Richards. Krüger has published three collections of his works, and has a yearly art calendar from Morpheus International. Krüger's art can be seen frequently in Playboy magazine and has also been featured in the likes of Stern, L’Espresso, Penthouse, and Der Spiegel and USA Today. He has recently been working on select motion picture projects.

- David Levine (1926–2009, American) is noted for his caricatures in The New York Review of Books and Playboy magazine. His first cartoons appeared in 1963. Since then he has drawn hundreds of pen-and-ink caricatures of famous writers and politicians for the newspaper.

- Sam Viviano (1953, American) has done much work for corporations and in advertising, having contributed to Rolling Stone, Family Weekly, Reader's Digest, Consumer Reports, and Mad, of which he is currently the art director. Viviano's caricatures are known for their wide jaws, which Viviano has explained is a result of his incorporation of side views as well as front views into his distortions of the human face. He has also developed a reputation for his ability to do crowd scenes. Explaining his twice-yearly covers for Institutional Investor magazine, Viviano has said that his upper limit is sixty caricatures in nine days.

Une discussion littéraire à la deuxième Galerie by Honoré Daumier

Une discussion littéraire à la deuxième Galerie by Honoré Daumier

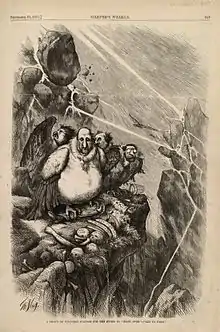

Lithograph published in Le Charivari newspaper, February 27, 1864 A Group of Vultures Waiting for the Storm to "Blow Over"—"Let Us Prey." by Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly newspaper, September 23, 1871.

A Group of Vultures Waiting for the Storm to "Blow Over"—"Let Us Prey." by Thomas Nast, Harper's Weekly newspaper, September 23, 1871. Print advertisement for U.S. Savings Bonds, featuring a caricature of Groucho Marx

Print advertisement for U.S. Savings Bonds, featuring a caricature of Groucho Marx

Computerization

There have been some efforts to produce caricatures automatically or semi-automatically using computer graphics techniques. For example, a system proposed by Akleman et al.[10] provides warping tools specifically designed toward rapidly producing caricatures. There are very few software programs designed specifically for automatically creating caricatures.

Computer graphic system requires quite different skill sets to design a caricature as compared to the caricatures created on paper. Thus, using a computer in the digital production of caricatures requires advanced knowledge of the program's functionality. Rather than being a simpler method of caricature creation, it can be a more complex method of creating images that feature finer coloring textures than can be created using more traditional methods.

A milestone in formally defining caricature was Susan Brennan's master's thesis[11] in 1982. In her system, caricature was formalized as the process of exaggerating differences from an average face. For example, if Charles III has more prominent ears than the average person, in his caricature the ears will be much larger than normal. Brennan's system implemented this idea in a partially automated fashion as follows: the operator was required to input a frontal drawing of the desired person having a standardized topology (the number and ordering of lines for every face). She obtained a corresponding drawing of an average male face. Then, the particular face was caricatured simply by subtracting from the particular face the corresponding point on the mean face (the origin being placed in the middle of the face), scaling this difference by a factor larger than one, and adding the scaled difference back onto the mean face.

Though Brennan's formalization was introduced in the 1980s, it remains relevant in recent work. Mo et al.[12] refined the idea by noting that the population variance of the feature should be taken into account. For example, the distance between the eyes varies less than other features, such as the size of the nose. Thus even a small variation in the eye spacing is unusual and should be exaggerated, whereas a correspondingly small change in the nose size relative to the mean would not be unusual enough to be worthy of exaggeration.

On the other hand, Liang et al.[13] argue that caricature varies depending on the artist and cannot be captured in a single definition. Their system uses machine learning techniques to automatically learn and mimic the style of a particular caricature artist, given training data in the form of a number of face photographs and the corresponding caricatures by that artist. The results produced by computer graphic systems are arguably not yet of the same quality as those produced by human artists. For example, most systems are restricted to exactly frontal poses, whereas many or even most manually produced caricatures (and face portraits in general) choose an off-center "three-quarters" view. Brennan's caricature drawings were frontal-pose line drawings. More recent systems can produce caricatures in a variety of styles, including direct geometric distortion of photographs.

Recognition advantage

Brennan's caricature generator was used to test recognition of caricatures. Rhodes, Brennan and Carey demonstrated that caricatures were recognised more accurately than the original images.[14] They used line drawn images but Benson and Perrett showed similar effects with photographic quality images.[15] Explanations for this advantage have been based on both norm-based theories of face recognition[14] and exemplar-based theories of face recognition.[16]

Modern use

Beside the political and public-figure satire, most contemporary caricatures are used as gifts or souvenirs, often drawn by street vendors. For a small fee, a caricature can be drawn specifically (and quickly) for a patron. These are popular at street fairs, carnivals, and even weddings, often with humorous results.[17]

Caricature artists are also popular attractions at many places frequented by tourists, especially oceanfront boardwalks, where vacationers can have a humorous caricature sketched in a few minutes for a small fee. Caricature artists can sometimes be hired for parties, where they will draw caricatures of the guests for their entertainment.[18]

Museums

There are numerous museums dedicated to caricature throughout the world, including the Museo de la Caricatura of Mexico City, the Muzeum Karykatury in Warsaw, the Caricatura Museum Frankfurt, the Wilhelm Busch Museum in Hanover and the Cartoonmuseum in Basel. The first museum of caricature in the Arab world was opened in March, 2009, at Fayoum, Egypt.[19]

See also

References

- "Caricature in literature". Contemporarylit.about.com. 2012-04-10. Archived from the original on 2013-01-12. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

- Lynch, John (1926). A History of Caricature. London: Faber & Dwyer.

- Mosher, Terry. "Drawn and Quartered." Leader and Dreamers Commemorative Issue. Maclean's. 2004: 171. Print.

- Preston O (2006). "Cartoons... at last a big draw". Br Journalism Rev. 17 (1): 59–64. doi:10.1177/0956474806064768. S2CID 144360309.

- See the Tate Gallery's exhibit "James Gillray: The Art of Caricature" Archived 2014-07-29 at the Wayback Machine. Accessed July 21, 2014

- "Vanity Fair cartoons: drawings by various artists, 1869-1910". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- Ted Harrison lecture, The History and Art of Caricature, September 2007, Queen Mary 2 Lecture Theatre

- The Slave in European Art: From Renaissance Trophy to Abolitionist Emblem, ed Elizabeth Mcgrath and Jean Michel Massing, London (The Warburg Institute)2012

- NYPL.org Archived 2009-02-10 at the Wayback Machine, the New York Public Library Inventory of the Sardi's caricatures, 1925–1952.

- E. Akleman, J, Palmer, R. Logan, "Making Extreme Caricatures with a New Interactive 2D Deformation Technique with Simplicial Complexes", Proceedings of Visual 2000, pp. Mexico City, Mexico, pp. 165–170, September 2000. See the author's examples on VIZ-tamu.edu Archived July 1, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- Susan Brennan, The Caricature Generator, MIT Media Lab master's thesis, 1982. Also see Brennan, Susan E. (1985). "Caricature Generator: The Dynamic Exaggeration of Faces by Computer". Leonardo. 18 (3): 170–8. doi:10.2307/1578048. ISSN 1530-9282. JSTOR 1578048. S2CID 201767411.

- Mo, Z.; Lewis, J.; Neumann, U. (2004). "ACM SIGGRAPH 2004 Sketches on - SIGGRAPH '04". ACM Siggraph. p. 57. doi:10.1145/1186223.1186294. ISBN 1-58113-896-2.

- L. Liang, H. Chen, Y. Xu, and H. Shum, Example-Based Caricature Generation with Exaggeration, Pacific Graphics 2002.

- Rhodes, Gillian; Brennan, Susan; Carey, Susan (1987-10-01). "Identification and ratings of caricatures: Implications for mental representations of faces". Cognitive Psychology. 19 (4): 473–497. doi:10.1016/0010-0285(87)90016-8. PMID 3677584. S2CID 41097143.

- Benson, Philip J.; Perrett, David I. (1991-01-01). "Perception and recognition of photographic quality facial caricatures: Implications for the recognition of natural images". European Journal of Cognitive Psychology. 3 (1): 105–135. doi:10.1080/09541449108406222. ISSN 0954-1446.

- Lewis, Michael B.; Johnston, Robert A. (1998-05-01). "Understanding Caricatures of Faces". The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology Section A. 51 (2): 321–346. doi:10.1080/713755758. ISSN 0272-4987. PMID 9621842. S2CID 13022741.

- McGlynn, Katla (June 16, 2010). "Street Portraits Gone Wrong: The Funniest Caricature Drawings Ever (PICTURES)". Huffingtonpost.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2010. Retrieved 2010-12-31.

- "Caricature artist for hire in modern use". YTEevents. Archived from the original on 2021-04-22.

- "A sanctuary for Egyptian caricature opens in Fayoum". Daily News Egypt (Egypt). Daily News Egypt. 4 March 2009. Archived from the original on 5 May 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2012.

External links

- International Society of Caricature Artists (ISCA) Official site of the International Society of Caricature Artists – a non-profit association devoted to the art of caricature (Formerly the National Caricaturist Network (NCN))

- Daumier Drawings, an exhibition catalog from The Metropolitan Museum of Art (fully available online as PDF), which focuses on this great caricaturist

- Spielmann, Marion Harry Alexander (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 5 (11th ed.). pp. 331–336.