Llangelynnin, Conwy

Llangelynnin (ⓘ; Welsh for The church of Celynnin) is a former parish in the Conwy valley, in Conwy county borough, north Wales. Today the name exists only in connection with the church, a school in the nearby village of Henryd, and the nearby mountain ridge, Craig Celynnin.

Llangelynnin Church (Welsh: Eglwys Llangelynnin) is possibly one of the remotest churches in Wales (53.2458°N 3.8730°W), and is amongst the oldest; that at Llanrhychwyn, further up the valley, is a little older. The church is dedicated to Saint Celynnin, who lived in the 6th century and probably established the first religious settlement here. It lies at a height of about 280 metres (920 ft) feet, above the village of Henryd in the Conwy valley, in the shelter of Tal y Fan (610 metres, 2,001 ft), the mountain to the south-west.

A small and simple building, it probably dates from the 12th century (although some sources cite the 13th century), and was probably pre-dated by an earlier church of timber, or wattle and daub construction. Llangelynnin is also the name of the former parish, the primary school in nearby Henryd (Ysgol Llangelynnin). Celynnin's name is also carried by Craig Celynnin, a mountain ridge adjacent to the church.

St. Celynnin

Celynnin lived in the 6th century, and according to tradition was one of the sons of Helig ap Glanawg, a prince who lived at Llys Helig (in what is now known to a natural rock formation)[1] before the sea inundated the land off the coast of Penmaenmawr. It is said that Celynnin was related to Rhun, son of Maelgwn Gwynedd, Prince of Gwynedd, who is known to have ruled in the 6th century, and that he was also a brother to Rhychwyn, the saint associated with Llanrhychwyn church.

Location

Next to the church lie the remains of an Iron Age hut circle, and some stories romantically suggest that this was where St. Celynin himself lived. It is also reputed to have been used as a cockfighting ring. The church is overlooked from the north-east by the adjacent crags of Cerrig-y-ddinas, the site of an Iron Age hillfort. These crags afford wide views down the Conwy valley to the sea, and up the valley as far as Dolgarrog.

Pathways

Many old paths lie in the area, and these routes would have been established at a time when the hills were considerably more wooded.

An old walled bridleway route leads east from the church, down through Parc Mawr,[2] an area of woodland now owned by the Woodland Trust, who are replacing the Forestry Commission's 1960s-planted conifers with native species. The path through the wood leads towards the valley bottom, and to the west a route leads towards Penmaenmawr, past the Bronze Age standing stones of Maen Penddu. To the south-west a path meets the important Neolithic route and Roman Road passing through Bwlch-y-Ddeufaen, which connected the Conwy valley to the north coast near Llanfairfechan, and places further westwards.

The church building

The porch was added in the 15th century, and features an unusual "squint window" in its east (right) wall. Repairs to the porch roof were made using yew wood, and therefore it is quite possible that these came from the churchyard, which at one time contained trees. The door hinges and threshold date from the 14th century, although the door itself is more recent.

The nave is the oldest part of the church, dating from the 12th century, and the present chancel was added later, probably in the 14th century. Originally the nave would not have been paved, as it is today, and indeed, the rear of the north chapel remains unpaved even today. The roof contains dark oak rafters.

The north transept was added in the 15th century and was known as Capel Meibion, the "men's chapel". The window at the back of the chapel was a more recent addition.

Opposite the north transept, a south transept was also added, probably in the 16th century. This was called Capel Eirianws (meaning "Plum Orchard", the name of a local farm), whose owner possibly had it built. This chapel was demolished in the 19th century, but some remains are still visible from outside.

The present east window dates from the 15th century, and replaced a smaller 14th century window.

Since demolition of the south chapel (and the gallery) in the 19th century, the church has changed little.

Artifacts

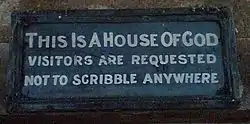

The twist-turned altar rails and the altar screen date from the 17th century. The removal of a pulpit to the left of the altar revealed inscriptions on the east wall, and further removal of whitewash revealed the Creed, the Lord's Prayer and the Ten Commandments, in Welsh. The inscription "Fear God and honour the King", together with scrollwork, can clearly be seen today, as can a skull and cross-bones! The Welsh version of the Lord's Prayer, on the sill, is hardly visible, after vandalism.

The remains of the rood screen in front of the more recent lectern date from the 14th century, and would have separated the nave from the chancel. The church once had a rood loft and gallery, and the remains of these can be seen in on the nave walls, and from the beam at the back of the church. The gallery was demolished in the 19th century.

The reader's desk possibly dates from the 16th century, although the door is more recent.

The wooden benches in the nave date from the 18th century, although at least one bench in the church dates from 1629.[3] One bench (at the front of the north chapel) still bears the initials R.O.B., this being the Reverend Owen Bulkeley, a former rector, who died in 1737. A church inventory of 1742 records a particular bench which was used by women only.

Just inside the church, on the wall, is a holy water stoup, used until the 19th century for making the sign of the Cross. At the back of the church is an octagonal font, which probably dates from the 13th or 14th century. The bell has no inscription and its date is therefore unknown.

On the wall in the nave is a bier, used to carry the dead to the churchyard.

Renovation

Major renovation of the church was carried out in 1932 and in 1987. This later renovation work was carried out under the guidance of Gerald Speechley, and a plaque in the church records this. He died three years later.

The churchyard

The churchyard is walled, with an arched entrance in the eastern wall. Today it is almost devoid of tree growth, but this was not always so.

The churchyard contains a fair number of gravestones, dating back to the 14th century. These graves were not dug in any uniform layout. Indeed, the rock outcrops to such a degree that finding space for graves has been a problem over the centuries.

The Holy Well

In the south-eastern corner of the churchyard is a well, Ffynnon Gelynin (sometimes known as "The Holy Well of St. Celynin"), a small walled rectangular pool, which was renowned for its power to cure sick children. One old story relates that parents would throw items of their sick child's clothing into the water. If the clothes floated their child would live. If they sank the child was destined to die of the illness. The well was once roofed over but this structure no longer exists. The walls around the well, and probably the benches too, were later additions made when the churchyard was restored. The presence of surface water at this elevation was probably the reason for its designation as a site for early settlement, and the holy well itself almost certainly predates the church.

Outside the churchyard

Outside the churchyard itself, close to the well, are the remains of a round building. A church terrier of 1742 refers to this, and to its use as a stable.

Beyond the south-east corner of the churchyard there was once an old inn, demolished in the 19th century.

Access to the church

Despite its remoteness, the church is well signposted from Henryd, which lies off the B5106 south of Conwy. The single track road is metalled up to the small car park below the church. The church is not named on the Ordnance Survey map, but lies at reference SH751737.

The church is open to visitors at most times. Only occasionally are services held in the church, in the summer and on special occasions.

The "new" church

Llangelynnin church was used regularly until 1840, when it closed following depopulation of the area. A new church was consequently built, carrying the same name, nearer the centres of population. This church is situated close to the 15th century Groes Inn (on the B5106 road), on the road which runs from the inn to the village of Rowen. Whereas the old church reflects a simple mediaeval design, the new church was designed by Thomas Jones of Chester in a much grander, lofty late Georgian style. Unusually, the tower has a square lower storey surmounted by an octagonal embattled upper stage. The original plans of 1839 still exist .

A plaque in the doorway refers to the "re-erection" of the building, implying perhaps that there was an earlier building on this site, but there is no evidence to this effect, and no gravestones pre-date 1839. The Religious Census of 1851 refers to it being erected in "1839 or 1840", but makes no reference to the Old Church.

This "new" church also eventually closed (in the 1980s), but the font from the church is now displayed by the altar in Llangelynnin old church. Llangelynnin "new" church is now the studio of David Chapman, a sculptor and artist.

Llangelynnin – The wider parish

The following extract comes from A Topographical Dictionary of Wales (1849) by Samuel Lewis :

LLANGELYNIN (LLAN-GELYNIN), a parish, in the union of Conway, hundred of LlêchWedd-Isâv, county of Carnarvon, North Wales, 3 miles (S. by W.) from Conway; containing 270 inhabitants. This parish, which derives its name from the dedication of its church to St. Celynin, who flourished towards the close of the sixth century, is situated at the north-eastern extremity of the county, bordering upon Denbighshire. A memorable battle was fought at Cymryd, in or near the parish, in the year 880, between the forces of Anarawd, Prince of North Wales, and those of Edred, Earl of Mercia, who attempted the conquest of the country. In this conflict Anarawd was completely victorious; he drove the Mercians from the field of battle, and continued to pursue them until they were finally expelled from the principality: the victory was called Dial Rhodri, or "Roderic's revenge," as Anarawd thus fully avenged the slaughter of his father Roderic in a descent of the Saxons upon Anglesey. The village, which is small, is beautifully situated in a fertile vale under the mountain called Tàl-y-Van. The surface of the parish is mountainous, the lands partially inclosed and cultivated, the soil various, and the surrounding scenery marked with features rather of boldness than of beauty. The living is a discharged rectory, rated in the king's books at £7; patron, the Bishop of Bangor. The incumbent's tithes have been commuted for a rent-charge of £250, and the glebe comprises five acres: a rent-charge of £5 is paid to the parish-clerk. The church is a small ancient edifice, in a state of considerable dilapidation. There are places of worship for Independents and Wesleyan Methodists; a day school in connexion with the Church, and a Sunday school belonging to the Independents. The Rev. Launcelot Bulkeley, in 1718, bequeathed £60, the interest to be paid to four widows, who are appointed at a vestry, and regularly receive the donation.

Notes

- Bird, Eric (2010). Encyclopedia of the World's Coastal Landforms. Springer. ISBN 978-1402086380.

- "Parc Mawr". Woodland Trust. Retrieved 26 October 2021.

- "Drysau Agored 2006 – Dyddiau Treftadaeth Ewropeaidd" [Open Doors 2006 – European Heritage Days] (PDF) (in Welsh). Conwy County Borough Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 June 2015. Retrieved 23 June 2015.

References

- The Old Churches of Snowdonia by Harold Hughes & Herbert North, Bangor, 1924

- The Conwy Valley & The Lands of History by K. Mortimer Hart, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 1987

- Terriers of Llangelynnin Church, held by Gwynedd Archives.

- Langelynnin Church's own information sheet