Censorship in Auschwitz

Censorship in Auschwitz concentration camp (German: Konzentrationslager Auschwitz; also K.L. Auschwitz) followed the broader pattern of political and cultural suppression in the Third Reich. General censorship in camp occurred in a variety of daily life topics and was more stringent than the outside world. The main focus was monitoring prisoners’ written correspondences, which was under strict censorship by the SS garrison on camp. Starting from 1939, the Mail Censorship Office (German: Postzensurstelle) which was directly subordinated to the commandant's office (German: Abteilung I) took the main responsibility for checking the contents of letters and parcels as well as receiving and sending correspondences. The SS personnel would cut or blacken suspicious content that was considered inappropriate i.e. any information regarded the true living condition of the concentration camp or prisoner's health status. Even worse, some prisoner's letters were never been sent out to their family members.

| Part of a series on |

| Censorship by country |

|---|

|

| Countries |

| See also |

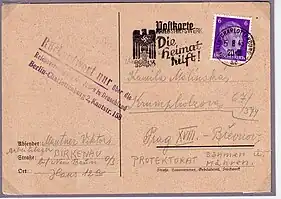

Only a small number of German and Polish prisoners were allowed to write and send correspondences. Selected prisoners were required to write in German, the official language of the Third Reich. In order to be successfully mailed, letters had to be written in 15 lines on standard stationery, signed with the sender's name and the belonged camp's name, and stamped at the upper right for general circulation. All letters need to contain the opening phrase “I am healthy and feel well” (German: “Ich bin gesund und fühle mich gut”), though it usually did not reflect the actual physical status of prisoners. The SS garrison in Auschwitz launched “Letter Operation” (German: Briefaktion) in March 1944. Jewish prisoners from the Theresienstadt ghetto in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia and Berlin were forced to write and send postcards to their families and friends. These unregistered prisoners were later liquidated in the gas chambers, while their relatives who received postcards were closely monitored by the Nazis. Despite that, prisoners had developed a set of approaches to evade being censored based on the camp ecology, such as writing in codes. The underground intelligence network in the vicinity of the camp further expanded secret correspondences to enable prisoners and their families to keep in touch, share information, and obtain resources for survival.

The censorship system ended in the camp with the collapse of the Third Reich and the liberation of Auschwitz in January 1945. In the postwar period, some of the Holocaust survivors and victims’ families donated the censored correspondences they received to the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum.

Background

In the Third Reich

Censorship in the Third Reich was the leading means for the Nazis to maintain Nazi propaganda and to promote the cult of Adolf Hitler. Joseph Goebbels and his Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda (German: Reichsministerium für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda; also RMVP) were central to the systematic suppression of the content of public communication, press, literature, art music, movies, theatre, and radio.[1]

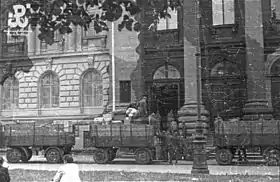

After the Nazi Book Burnings on May 10, 1933, in Berlin, large-scale extreme censorship began in Germany. Censorship was targeted for sanctioning or prohibiting works viewed as incompatible or subversive with Nazi ideology.[2] The core thoughts consisted of advocating antisemitism, anti-communism, social Darwinism, German nationalism, and the dictatorship of Hitler.[3] The Nazis adopted a variety of propaganda tools to execute censorship, such as banning works of Jewish and communist writers, selling cheap radios to the public for hearing Hitler's speeches, and glorying Hitler by using his image on stamps, postcards, and posters.[4] The campaign was later expanded to other regions in Nazi-occupied Europe with the invasion of the Wehrmacht.

In Nazi-occupied Poland

Following the German-Soviet invasion of Poland in 1939 (also the September Campaign), the occupying powers and their collaborationists committed a series of war crimes and crimes against humanity. As part of the Generalplan Ost (GPO) to colonize and destroy Poland, the Nazis launched severe censorship against Polish people.[5] Censorship and Nazi propaganda were submitted to the Department of Public Education and Propaganda (German: Fachabteilung für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda; also FAVuP), which was directed by the General Government in Kraków.[6] To achieve a complete Germanized Polish nation in political, cultural, economic, and ethnic aspects, the Nazis prohibited any publications in Polish, closed down all universities and academic institutions, looted and destroyed museums and libraries, organized book burnings, persecuted the Catholic church, and deported Polish scholars, scientists, and priests to concentration camps.[7] The propaganda campaign was executed for the purpose of assimilation, while anti-Slavic sentiment played a significant role in the annexation of greater Poland. Nazi censorship was perpetuated in concentration camps within Poland as well.

SS administration in Auschwitz

Like all other concentration camps, censorship in Auschwitz was managed and executed by the SS garrison with divided administrations in the camp. The Mail Censorship Office (German: Postzensurstelle) was the primary authority in charge of censorship of correspondences, which was directly subordinated to Division I, the commandant's office (German: Abteilung I - Kommandantur ).[8] The SS personnel employed at Postzensurstelle supervised the reception and sending of correspondence and censored the contents of prisoner's letters and postcards sent to the outside world.[9] To minimize administration costs, Postzensurstelle would order prisoner-functionaries in each block of Auschwitz to covey commands, monitor prisoners’ writings, and collect correspondences.[10]

Despite being an independent administrative unit, Postzensurstelle also collaborated with Division II, the political department (German: Abteilung II - Politische Abteilung) in examining and verifying prisoner's information.[11] The Section for Registration, Organization, and Documentation (German: Registratur, Organisation und Karteiführung) and the Identification Service (German: Erkennungsidenst) of Division II kept registered prisoner's personal records, fingerprints, photographs, numbers, and most significantly, their family addresses.[12] The correspondence campaign was in fact a way for the camp authorities to find out if any of the prisoners were registered under a false name or address. This helped to prevent escapes due to the threat of arresting the entire family.[13][14] Postzensurstelle’s remit of censorship later expanded to the subcamps of Auschwitz-II Birkenau and Auschwitz-III Monowitz in 1942.[15]

Censorship of correspondences

Writing and sending correspondences was part of the camp culture of Auschwitz. However, it was in fact a privilege that was reserved for a small number of prisoners. Only a small number of German- and Polish-ethnic prisoners were allowed to write and send correspondences.[16] Unregistered prisoners and prisoners with the designation “Nacht und Nebel” (NN), including Soviet prisoners-of-war, Jewish and half-Jewish prisoners, and prisoners whose families lived in non-Nazi jurisdictional areas were excluded to correspond.[17] A regulation from March 30, 1942, limited the amount of correspondence that could be carried out by people from the East (German: Ostvölker).[18] They were allowed to send and receive only one letter every two months, while they had to use the returnable card to correspond (German: Karten mit Rückantwort).[19][20] Selected prisoners were required to write in German, the official language of the Third Reich, while Polish, Silesian, and Yiddish were strictly banned.[21]

The retained letters demonstrate the official regulation of correspondence censorship in Auschwitz. Prisoners were only allowed to write on uniformly distributed camp stationery. On the left upper of the stationery was the regulation of correspondence:

- Every prisoner in protective custody can receive two letters or cards from his relatives, or send to them. Letters to prisoners must be legibly written in ink and no more than 15 lines per page. Only one sheet of standard letterhead is permitted. Large envelopes must be unlined. Only 5 stamps of 12 pence may be enclosed in a letter. Anything else is prohibited and subject to confiscation;

- Postcards must be written in 10 lines. Photographs may not be used as postcards;

- Sending money is permitted;

- It is important to note that when it comes to money or mail, the exact address consists of name, date of birth, and prisoner number need to be included. If the address is wrong, the correspondence will be returned to the sender or destroyed;

- Newspapers are permitted, but may only be sent through the post office of the K.L. Auschwitz ordered;

- Parcels may not be sent, since the prisoners can buy everything in the camp;

- Requests for release from protective custody to the camp management are pointless;

- Permission to speak and visits prisoners in the concentration camp are generally not permitted.[22]

Therefore, only two letters or postcards were allowed to send every month per prisoner. Parcels were not allowed. In order to be mailed successfully, letters had to be written in 15 lines on standard stationery and in ink, signed with the sender's name and the belonged camp's name, and put in standard envelopes with a Geprüft stamp. Prisoners were not permitted to attach or enclose anything in letters, especially photographs. Money transactions were surprisingly allowed, and yet, the SS personnel in the camp embezzled most of it. The SS personnel and prisoner-functionaries took great advantage of the resources that prisoners’ families sent.[23] All letters need to contain the opening phrase “I am healthy and feel well” (German: “Ich bin gesund und fühle mich gut”), no matter what the prisoner's physical condition was.[24][25] These letters could not reveal the camp's reality, such as starvation, torture, dehydration, and sickness.[26] Marian Henryk Serejski (1897-1975), a former Polish prisoner of Auschwitz, also a Holocaust survivor, included his 25 letters from 1941 to 1942 in his book I Feel Healthy and I Feel Fine (2010) (Polish: Jestem zdrów i czuję się dobrze).[27] The example below reflect that prisoners’ correspondence did not exist as an effective means of communication with the outside world:

Dear wife and children,

On January 19 I wrote you my first letter from Auschwitz, and now I am waiting impatiently for news from you. I hope you are all healthy and have received my letter. I am working here and I am healthy. I repeat that no parcels are allowed, but you are allowed to send me money (10 to 20 Reichsmark) and, in a letter, to send 5 German 12 penny stamps. I am very curious how you are, my dear wife, and whether you don’t worry too much, whether our children and grandmother are healthy, whether Krysia is already a big and beautiful girl and whether Leszek is growing up to become a fine boy. Write to me, dearest, about how our relatives and friends are doing, and whether anyone would be willing to help Henryk who is not in the best situation now. You can write to me twice a month just as I can write to you. Let me know whether there is a post office in Łysobyki.

I kiss you and our dear children and grandmother. Greetings to friends. Your Marian.[28]

Serejski's letter to his family went through severe censorship, and this circumstance happened to other prisoners’ correspondences. When the letters were censored, the SS personnel from Postzensurstelle would cut or blacken suspicious words or sentences, sometimes entire passages would be deleted.[29] Letters containing excessive “inappropriate” content would be directly detained and never sent.[30] Division I and II had never officially released any clear regulations on the content of correspondence, which undoubtedly increase prisoners’ fear of the censorship system since they could only successfully contact the outside through guessing or bribing personnel in the camp.[31] This measurement further strengthened the camp authorities’ control over prisoners.

Briefaktion, 1942-1944

The “Letter Operation” (German: Briefaktion) was a secret undertaking that involved forcing Jewish prisoners to send correspondence to their family members residing in Nazi-occupied areas and ghettos, in order to calm the general fear about deportation to concentration camps.[32] The earliest such operation began in mid-December 1942, while Jewish prisoners’ letters arrived in Jewish communities in the Netherlands.[33]

At the beginning of March 1944, Briefaktion was unfolded in Auschwitz, which applied to Jewish prisoners who arrived in Auschwitz and Birkenau.[34] Prisoners who were deported from the Theresienstadt ghetto in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia and Berlin provide direct evidence of this operation.[35] On March 5, Jewish prisoners received special postcards, which they were forced to send back to their families and friends.[36] The stamp on postcards informed recipients that these correspondences were passed through the Reich's Union for Jews in Germany (German: Reichsvereinigung der Juden).[37] Prisoners were ordered to falsely state the conditions in the concentration camp that

“The food is good since hot dinner is served at noon and in the evening bread with cheese and jam [...] We have central heating here and sleep covered with two blankets. We also have showers outfitted in a practical way, with running cold and hot water.”[38]

These unregistered prisoners were later liquidated in the gas chambers, while their relatives who received postcards remained convinced that they were still alive at the “work camp” Birkenau.[39][40] The operation was repeated several times to deceive Jews and the world about the existence of extermination camps (German: Vernichtungslager).[41]

Censorship of art

Creating artwork in concentration camps is obviously forbidden. Harsh punishments would be made to prisoners for making art that was not commanded by the camp authorities.[42] Besides, painting materials were difficult to obtain in camps with extremely scarce supplies.[43] There were more than 300 artists confined in Auschwitz-Birkenau from 1940 until 1945.[44] Most artists did not have the opportunity to create in the camp, and most of the preserved artworks were not created by professional artists. They were self-taught, learnt from other prisoners, or just felt urgent to paint what they had lived.[45] In Auschwitz, prisoners commanded art and clandestine/illegal art proceeded simultaneously.

“Commanded art” are officially approved paintings and other formats of artwork created by prisoners who were working under the commission of the SS personnel in the camp.[46] Prisoners assigned to SS offices and workshops were forced to make instructional drawings, models and visualizations of the plans for expanding the camp, visual depictions to record illnesses and medical experiments, and even signs for the barracks such as “in case of fire instructions.”[47] Prisoners were also exploited to fulfill SS personnel's personal demands, such as drawing portraits, landscapes, greeting cards, gift objects, and decorations.[48] These prisoner-artists usually worked indoors, which provided shelter from the harsh outdoor working conditions and potential dehydration and sickness.[49]

Contrary to the commanded art, creating “clandestine/illegal art” in the camp was not a way to secure one's life but a way of risking it.[50] These artworks were made in secret, sometimes coming from other prisoners’ requests. Prisoners created portraits, postcards, devotional objects, daily sketches, and even satirical comics targeting the camp authorities.[51] These paintings circulated in the camp's black market and were smuggled immediately to the outside world, while prisoner-artists could get a piece of bread or extra food in exchange for them.[52] Prisoners created illegal artworks as a way of witnessing, documenting, and rebelling against the cruel censorship of Auschwitz. Also, whether to the creator or to the client, illegal artwork was empowered to guide a spiritual tranquillity. For instance, the former prisoner of Auschwitz and the Holocaust survivor Zofia Stępień-Bator (1920-2019) drew portraits of her fellow prisoners. Her most well-known work is the portrait of Malka “Mala” Zimetbaum (1918-1944).[53] She painted female prisoners with fashionable hairstyles, exquisite makeup, and beautiful clothes which was banned in the camp but what prisoners dreamed of.[54]

The SS garrison in Auschwitz employed more than 100 prisoners who were trained as housepainters, varnishers, and sign painters before the war to establish a painting workshop.[55] They obtained painting materials from the Canada warehouses (German: Kanada) in Block 26, where stored the confiscated belongings of the Jews arrived at Auschwitz.[56] These prisoners managed to keep and smuggle some of the painting materials out of the workshop for the production of illegal art.[57]

Resistance

Nostalgia, as the most common theme in Holocaust survivors’ memoirs and testimonies, reveals prisoners’ efforts to keep contact with their families and friends in or out of the camp. Despite being extremely suppressed by the censorship system in Auschwitz, receiving correspondence from families was usually the high point in prisoners’ daily lives which encouraged their hope of survival. Meanwhile, to avoid being censored in order to contact the outside world, prisoners developed a series of means to minimize the negative effect of censorship. Polish native speakers would request German native speakers or prisoners who were fluent in German to ghostwrite. Prisoners adopted “self-censorship” by writing on only one side of the stationary to avoid losing sentences when “inappropriate” words were cut from the other side.[58] Even more, some prisoners wrote in code or cipher to smuggle out important information.[59] Prisoner Zbigniew Kączkowski wrote in a secret language to suggest his family move to escape the Gestapo,

“[...] My wife and little daughter were living in Warsaw, but I informed her of my plan and advised her to change their place of residence [...] I wrote more or less as follows, ‘I applaud your intended trip to the countryside. The fresh air will do you good. Especially since Szczepan (my middle name) is planning, as you write, to change his place of work.”[60]

Similarly, prisoner Władysław Dyrek wrote in pseudonyms to his family to inform his increasingly weak health status:

“In reference to myself, in my letters, I used the pseudonym ‘Uncle Miecio.’ Thus, I was able to inform my family about my situation, e.g. ‘Uncle Miecio wrote to me that he had had typhus and was very weak and exhausted.’”[61]

Moreover, the establishment of the underground intelligence network in the town of Oświęcim contributed to helping prisoners to maintain contact with their loved ones. This movement took the form of local residents acting as intermediaries in the circulation of secret messages from the camp and correspondences from home.[62] These underground movement organizations had safe houses in Oświęcim and Katowice, mailed food parcels to Auschwitz, and transmitted secret information within Poland and even in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.[63] The courier of the Oświęcim District ZWZ/AK Wojciech Jekiełek reports that

“A short time after we began our operations, I was forced to organize a whole range of ‘letter boxes’ where letters, photographs, and other keepsakes arrived from all over Poland for the prisoners. These were delivered through the mail or by other means to the real names and addresses of people we trusted. Afterwards, we used illegal channels to pass them on to the prisoners in the camp. Correspondence from the prisoners to their families or to other people close to them was sent the same way.”[64]

The couriers from the underground organizations worked as agents to arrange secret meetings between prisoners and their families as well.[65] However, this kind of help could only be offered to Polish prisoners and sometimes to Czech citizens.[66] Prisoners with other ethnic backgrounds, such as Jewish, Romani, and Soviet POWs were unreachable due to their locations within the ghettos, transit camps, and on the trains on their way to Auschwitz or other extermination camps.[67] Nonetheless, correspondences from some minority groups were discovered and exposed after the war. Agnes-Sulejka Klein, a Romani prisoner who was deported to Auschwitz at the age of 16, raped by a prisoner-functionary and suffered from miscarriage, wrote in letters about the harsh condition in the “gypsy camp.”

“We often had to stand in the open for hours, no matter what the weather, with rain and snow, wind and cold, with hardly any clothes on our backs and the children with us. They died like flies.”[68]

Postwar memories of censorship

Collecting Holocaust survivors' memories of censorship in concentration camps became an extreme task because most of them lived in the Eastern Bloc after the war, while they suffered from severe censorship systems still. Some Polish survivors of Auschwitz, however, recounted the experience of receiving parcels from home as the only consolation in the life of confronting camp terror. Henry Zguda, a Polish survivor who spent 3 and a half years in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, depicts how food parcels greatly increased the prisoners’ ability and will to survive.[69] He received parcels from his mother twice. Parcels, including food and other precious commodities, were used to barter for bread or bribe a guard. These resources from the outside world greatly contributed to the establishment of the camp's black market.[70]

The hierarchy within Auschwitz that resulted from its original usage created more power dynamics among prisoners. Auschwitz I was initially used as a “protective custody” camp for prisoning Polish political prisoners, Catholic priests, and religious prisoners as it opened in May 1940. The first groups of Soviet POWs arrived in Auschwitz on June 22, 1941.[71] The first mass transport of Jews to Auschwitz happened on March 25, 1942.[72] Due to the higher number of Polish prisoners and their earlier occupation of better jobs, Polish prisoners, especially those with fluent German who could respond to the SS personnel's commands quickly, rose quickly in the camp hierarchy.[73] In other words, the censorship of prisoners' correspondences was an exclusive system. Non-German and Polish prisoners left extremely limited testimonies of the censorship in Auschwitz.

See also

References

Citations

- "Nazi Propaganda and Censorship." The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Accessed in August 16, 2023.

- "Nazi Propaganda and Censorship."

- Richard J. Evans. The Coming of the Third Reich (New York: Penguin Books, 2012), 109.

- "Nazi Propaganda and Censorship."

- Richard C. Lukas. The Forgotten Holocaust: The Poles Under German Occupation (New York: Hippocrene Books, 2001), 198.

- Lukas, 199.

- Lukas, 199-200.

- Tadeusz Iwasko, "The Daily Life of Prisoners," in Danuta Czech, Auschwitz: Nazi Death Camp (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 1996), 84.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- Iwaszko, 84-85.

- Aleksander Lasik, "Structure and Character of the Camp SS Administration" in Danuta Czech, et al. Auschwitz: Nazi Death Camp (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 1996), 45.

- Lasik, 47.

- Lasik, 47-48.

- Piotr M.A. Cywiński, Auschwitz: A Monograph on the Human. (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2022), 317.

- Cywiński, 319.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- APMO, D-RF-9/WVHA/8, Collection Sammlung von Erlässen, card 31.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- APMO, D-RF-9/WVHA/8, Collection Sammlung von Erlässen, card 31.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- APMO, D-Au-I/4167. Collection of letters and camp correspondence cards, vol. 2 (hardcopies), letter 1.

- Cywiński, 318.

- Iwaszko, 48.

- Marian Henryk Serejski, I Am Healthy and I Feel Fine: The Auschwitz Letters of Marian Henryk Serejski (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2010), 3.

- Cywiński, 317-18.

- Serejski, 1-2.

- Serejski, 73.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- Iwaszko, 84.

- Cywiński, 345.

- Piotr M.A. Cywiński, Jacek Lachendro, Piotr Setkiewicz, Auschwitz from A to Z: An Illustrated History of the Camp (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2017), 21.

- Cywiński, Lachendro, and Setkiewicz, 21.

- Iwaszko, 85.

- Iwaszko, 85.

- Iwaszko, 85.

- APMO, D-Au-I/4167. Collection of letters and camp correspondence cards, vol. 20 (photocopies), card 15.

- Cywiński, Lachendro, and Setkiewicz, 21.

- Iwaszko, 85.

- Cywiński, Lachendro, and Setkiewicz, 21.

- Cywiński, Lachendro, and Setkiewicz, 21.

- Sybil Milton, "Art in the Context of Auschwitz," in Art and Auschwitz (Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2003), 61.

- Milton, 61-62.

- "Art in/from Auschwitz." Yad Vashem, Teaching about Auschwitz. Accessed in August 15, 2023.

- Milton, 62.

- Milton, 65.

- The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. "Works of art" in Historical Collection. Accessed in August 15, 2023.

- "Works of art."

- "Art in/from Auschwitz."

- "Art in/from Auschwitz."

- "Works of art."

- Milton, 70.

- Adam Cyra, “The Romeo and Juliet from Birkenau” in Pro Memoria, vol. 5 (Information Bulletin of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and the Memorial Foundation for the Commemoration of the Victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Camp, Poland: 1987), 28.

- The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, "Art of camp and postcamp period" in Gallery.

- "Art in/from Auschwitz."

- "Art in/from Auschwitz."

- "Art in/from Auschwitz."

- APMO, D-Au-I/4167. Collection of letters and camp correspondence cards, vol. 4 (hardcopies), letter 15-20.

- Henryk Świebocki, People of Good Will (Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2014), 133.

- Zbigniew Kączkowski, Account in Testimonies, vol. 21, 147.

- Władysław Dyrek, Account in Memoirs, vol. 52, 94.

- Świebocki, 131.

- Świebocki, 131-32.

- Świebocki, 110.

- Świebocki, 134.

- Świebocki, 110.

- Świebocki, 111.

- The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, "Nazi Genocide of the Sinti and Roma" in National Exhibition.

- Katrina Shawver, "Letters from Oblivion: Auschwitz and Buchenwald." Warfare History Network. Accessed in August 16, 2023.

- Shawver, "Letters from Oblivion: Auschwitz and Buchenwald."

- The Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. "Soviet POWs." History. Accessed in August 16, 2013.

- Shawver, "Letters from Oblivion: Auschwitz and Buchenwald."

- Shawver, "Letters from Oblivion: Auschwitz and Buchenwald."

Bibliography

- Birenbaum, Halina. Hope Is the Last to Die. Translated by David Welsh. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2016.

- Cyra, Adam. “The Romeo and Juliet from Birkenau.” In Pro Memoria, vol. 5 (Information Bulletin of the Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum and the Memorial Foundation for the Commemoration of the Victims of Auschwitz-Birkenau Extermination Camp), Poland: 1987.

- Cywiński, Piotr M.A. Auschwitz: A Monograph on the Human. Translated by Witold Zbirohowski-Kościa. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2022.

- Cywiński, Piotr M.A., Lachendro, Jacek, Setkiewicz, Piotr. Auschwitz from A to Z: An Illustrated History of the Camp. Edited by Jarosław Mensfelt and Jadwiga Pinderska-Lech. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2017.

- Czech, Danuta, et al. Auschwitz: Nazi Death Camp. Translated by Douglas Selvage. Edited by Franciszek Piper and Teresa Swiobocka. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 1996.

- Evans, Richard J. The Coming of the Third Reich. New York: Penguin Books, 2012.

- Lukas, Richard C. (2001). The forgotten Holocaust: the Poles under German occupation ; 1939 - 1944 (1st ed.). New York: Hippocrene Books. ISBN 9780781809016.

- Levi, Primo. If This Is a Man. Translated by Stuart Woolf. London: Abacus, 2003.

- Milton, Sybil. "Art in the Context of Auschwitz." In The Last Expression: Art and Auschwitz, Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2003.

- Serejski, Marian Henryk. I Am Healthy and I Feel Fine: The Auschwitz Letters of Marian Henryk Serejski. Edited by Krystyna Serejska Olszer. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2010.

- Shawver, Katrina. "Letters from Oblivion: Auschwitz and Buchenwald." Warfare History Network. Accessed in August 16, 2023.

- Świebocki, Henryk. People of Good Will. Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum, 2014.

- Sobolewicz, Tadeusz (1998). But I survived (in Polish). Oświęcim: Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum. ISBN 9788385047636.

External links

- "Archives." Museum. Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

- "Art of camp and postcamp period." Gallery. Auschwitz-Birkenau Museum.

- "Nazi propaganda and censorship." Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

- "'We Shall Meet Again:' Last Letters from the Holocaust, 1941." Exhibitions. Yad Vashem.