Portuguese dogfish

The Portuguese dogfish (Centroscymnus coelolepis) or Portuguese shark, is a species of sleeper shark of the family Somniosidae. This globally distributed species has been reported down to a depth of 3,675 m (12,057 ft), making it the deepest-living shark known. It inhabits lower continental slopes and abyssal plains, usually staying near the bottom. Stocky and dark brown in color, the Portuguese dogfish can be distinguished from similar-looking species (such as the kitefin shark, Dalatias licha) by the small spines in front of its dorsal fins. Its dermal denticles are also unusual, resembling the scales of a bony fish. This species typically reaches 0.9–1 m (3.0–3.3 ft) in length; sharks in the Mediterranean Sea are much smaller and have distinct depth and food preferences.

| Portuguese dogfish | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Chondrichthyes |

| Order: | Squaliformes |

| Family: | Somniosidae |

| Genus: | Centroscymnus |

| Species: | C. coelolepis |

| Binomial name | |

| Centroscymnus coelolepis (Barbosa du Bocage & Brito Capello, 1864) | |

| |

| Range of the Portuguese dogfish | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Centroscymnus macrops* Hu & Li, 1982 * ambiguous synonym | |

Relatively common, the Portuguese dogfish is an active hunter capable of tackling fast, large prey. It feeds mainly on cephalopods and fishes, though it also consumes invertebrates and cetacean carrion. This shark has acute vision optimized for detecting the bioluminescence of its prey, as sunlight does not reach the depths at which it lives. The Portuguese dogfish is aplacental viviparous, with the young provisioned by yolk and perhaps uterine fluid. The females give birth to up to 29 young after a gestation period of over one year. Valued for its liver oil and to a lesser extent meat, Portuguese dogfish are important to deepwater commercial fisheries operating off Portugal, the British Isles, Japan, and Australia. These fishing pressures and the low reproductive rate of this species have led the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) to assess it as Near Threatened.

Taxonomy

The first scientific description of the Portuguese dogfish was published by Portuguese zoologists José Vicente Barbosa du Bocage and Félix António de Brito Capello, in an 1864 issue of Proceedings of the General Meetings for Scientific Business of the Zoological Society of London.[2] They created the new genus Centroscymnus for this shark, and gave it the specific epithet coelolepis, derived from the Greek koilos ("hollow") and lepis ("fish scale") and referring to the structure of the dermal denticles.[3] The type specimen, caught off Portugal, has since been destroyed in a fire.[2]

Distribution and habitat

One of the widest-ranging deepwater sharks, the Portuguese dogfish is patchily distributed around the world.[4] In the western Atlantic, it occurs from the Grand Banks of Newfoundland to the U.S. state of Delaware. In the eastern Atlantic, it is found from Iceland to Sierra Leone, including the western Mediterranean Sea, the Azores and Madeira, as well as from southern Namibia to western South Africa.[2] In the Indian Ocean, this species has been caught off the Seychelles.[5] In the Pacific, this shark occurs off Japan, New Zealand, and Australia from Cape Hawke, New South Wales, to Beachport, South Australia, including Tasmania.[1]

The deepest-living shark known,[6] the Portuguese dogfish has been reported at depths of 150 m (490 ft) to 3,675 m (12,057 ft) from the lower continental slope to the abyssal plain, and is most common between 400 m (1,300 ft) and 2,000 m (6,600 ft).[1][7] This species is found deeper in the Mediterranean, seldom occurring above a depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and being most common at 2,500–3,000 m (8,200–9,800 ft).[8] The deep Mediterranean has a relatively constant temperature of 13 °C (55 °F) and a salinity of 38.4 ppt, whereas in the deep ocean the temperature is generally only 5 °C (41 °F) and the salinity 34–35 ppt.[9] The Portuguese dogfish is essentially benthic in nature, though young sharks can be found a considerable distance off the bottom.[2][10] There is depth segregation by size and sex; pregnant females are found in shallower water, above 1,200–1,500 m (3,900–4,900 ft), while juveniles are found deeper.[1][8][11] There may be several separate populations in the Atlantic, and sharks in the Mediterranean and off Japan appear to be distinct as well.[12]

Description

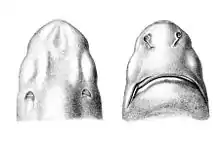

The Portuguese dogfish typically reaches a length of 0.9 m (3.0 ft) for males and 1.0 m (3.3 ft) for females, though specimens up to 1.2 m (3.9 ft) long have been recorded.[13] Sharks in the Mediterranean are smaller, growing no more than 65 cm (26 in) long.[4] This species has a flattened, broadly rounded snout that is shorter than the mouth is wide. The nostrils are preceded by short flaps of skin.[2] The eyes are large and oval in shape, positioned laterally on the head and equipped with a reflective tapetum lucidum that produces a yellow-green "eye shine".[14] The mouth is wide and slightly arched, with moderately thick, smooth lips and short furrows at the corners extending onto both jaws. The upper teeth are slender and upright with a single cusp, numbering 43–68 rows. The lower teeth have a short, strongly angled cusp and number 29–41 rows; their bases interlock to form a continuous cutting surface.[13] The five pairs of gill slits are short and nearly vertical.[15]

The body of the Portuguese dogfish is thick and cylindrical except for the flattened belly. The two dorsal fins are small and of similar size and shape, each bearing a tiny grooved spine in front. The first dorsal fin originates well behind the pectoral fins, while the second dorsal originates over the middle of the pelvic fin bases. The pectoral fins are medium-sized with a rounded margin. There is no anal fin. The caudal fin has a short but well-developed lower lobe and a prominent ventral notch near the tip of the upper lobe.[2] The very large dermal denticles change in shape with age: in juveniles, they are widely spaced and heart-shaped with an incomplete midline ridge and three posterior points, while in adults they are overlapping, roughly circular, smooth, and flattened with a round central concavity, superficially resembling the scales of bony fishes.[16] Young sharks are a uniform blue-black in color, while adults are brown-black; there are no prominent fin markings.[13] In 1997, a partially albino individual, with a pale body but normal eyes, was caught in the northeastern Atlantic. This represented the first documented case of albinism in a deep-sea shark.[17]

Biology and ecology

Living almost exclusively in the aphotic zone where little to no sunlight penetrates, the Portuguese dogfish is relatively common and the dominant shark species in deeper waters.[11][14] The large, squalene-rich liver of this shark allows it to maintain neutral buoyancy and hover with minimal effort; males contain more squalene in their livers than females.[18] A tracking study in the Porcupine Seabight has found that the Portuguese dogfish has an average swimming speed of 0.072 m/s (0.24 ft/s), and does not remain in any particular area for long.[19] This species may be preyed upon by larger fishes and sharks.[13] Known parasites of this species include monogeneans in the genus Erpocotyle,[20] and the tapeworms Sphyriocephalus viridis,[21] S. richardi, and Anthobothrium sp.[22]

An active predator of mobile, relatively large organisms, the Portuguese dogfish feeds mainly on cephalopods (including Mastigoteuthis spp.) and bony fishes (including slickheads, orange roughy, lantern fishes, and rattails). It has also been known to take other sharks and invertebrates (such as the medusa Atolla wyvillei), as well as scavenging from whale carcasses.[1][23] The Portuguese dogfish has more acute vision than many other deepsea sharks: in addition to having a large pupil and lens, and a tapetum lucidum, its eyes also contain a high concentration of ganglion cells mostly concentrated in a horizontal streak that is densest at the center; these cells impart highly sensitive motion detection along the horizontal plane. The visual system of this species appears adapted for detecting bioluminescence: the maximum absorption of its opsins correspond to the wavelengths of light emitted by favored prey, such as the squids Heteroteuthis dispar, Histioteuthis spp., Lycoteuthis lorigera, and Taningia danae.[14]

In the Mediterranean sea, the Portuguese dogfish is one of the most common deepwater sharks along with the blackmouth catshark (Galeus melastomus) and the velvet belly lantern shark (Etmopterus spinax), and the only shark abundant below a depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft).[8] By inhabiting deeper water, Portuguese dogfish in the Mediterranean may reduce competition with the other two species.[4] The smaller size of Mediterranean sharks relative to those from the rest of the world may be due to limited food availability and/or the warmer, saltier environment. Some 87% of the diet of Portuguese dogfish in the Mediterranean consists of cephalopods. Bony fishes are a secondary food source, while immature sharks favor the shrimp Acanthephyra eximia, the most common decapod crustacean in their environment.[9] Unlike in other regions, Mediterranean sharks seldom scavenge.[8]

Life history

The Portuguese dogfish is aplacental viviparous, with the female retaining eggs internally until they hatch. The embryos are sustained by yolk, and possibly also by uterine fluid secreted by the mother.[12] Figueiredo et al. (2008) reported that there are two breeding seasons per year off Portugal, from January to May and from August to December, with only a fraction of the population reproductively active at a time. However, previous accounts have described continuous reproduction with females in various stages of pregnancy present year-round.[12][24] The ovarian follicles take some time to mature; they are ovulated into the uterus at a diameter of 5–6 cm (2.0–2.4 in).[13] Studies of females have found no traces of sperm inside their reproductive tracts, which suggests that fertilization occurs immediately following copulation, which may also trigger ovulation. The reproductive cycles of Portuguese dogfish in the Atlantic and Pacific are generally similar; sharks off Japan tend to produce larger numbers of smaller oocytes than elsewhere, while sharks off the British Isles exhibit a larger litter size and birth size (but smaller oocytes) than those off Portugal. There is a record of a hermaphroditic specimen with an ovary on its right side and a testis on its left.[12]

Early in development, the embryos are sexually undifferentiated, unpigmented, and possess filamentous external gills; the external yolk sac in this stage weighs 120–130 g (4.2–4.6 oz). Recognizable sex organs develop by an embryonic length of 92 mm (3.6 in), and tissue differentiation is complete by a length of 150 mm (5.9 in). Body pigmentation appears when the embryo is 100–150 mm (3.9–5.9 in) long; the external gills regress at around the same time. An internal yolk sac develops when the embryo is 140 mm (5.5 in) long, which begins to take in yolk as the external yolk sac shrinks; by the time the embryo is 233–300 mm (9.2–11.8 in) long the external yolk sac has been completely resorbed.[12] Off Portugal, the young seem to be born in May and December following a gestation period of over a year. As they near giving birth, the females undergo ovarian atresia (regression of the follicles), suggesting that they enter a resting period afterwards.[24] The litter size ranges from 1 to 29 (typically 12), and is not correlated with female size.[1][12] Parturition may occur in a yet-unknown nursery area, as newborns are rarely ever caught.[12] The length at birth has been reported as 23–30 cm (9.1–11.8 in) in the Atlantic,[12][25] and 30–35 cm (12–14 in) in the Pacific.[26][27]

Aside from the distinctive Mediterranean population, Portuguese dogfish attain sexual maturity at similar sizes around the world: males and females mature at 90–101 cm (35–40 in) and 85–115 cm (33–45 in) respectively off the Iberian Peninsula,[12][24][25] 86 cm (34 in) and 102 cm (40 in) respectively west of the British Isles,[28] 70 cm (28 in) and 95–100 cm (37–39 in) respectively in Suruga Bay, Japan,[26] and 82–90 cm (32–35 in) and 99–110 cm (39–43 in) respectively off southeastern Australia.[27][29] In the Mediterranean, males mature at around 53 cm (21 in) long.[30]

Human interactions

The Portuguese dogfish is too small and occurs too deep to pose a danger to humans.[13] This species has long been commercially fished, using hook-and-line, gillnets, and trawls. It is mainly valued for its liver, which contains 22–49% squalene by weight and is processed for vitamins. The meat may also be sold fresh or dried and salted for human consumption, or converted into fishmeal.[1][7] An important fishery for the Portuguese dogfish exists in Suruga Bay for liver oil; catches peaked during World War II, but declined soon after from over-exploitation.[1] In the past few years, catches by the South East Trawl Fishery off Australia have been increasing, as fishers have been seeking out species not covered by commercial quotas following the relaxation of seafood mercury regulations. Shark landings in this fishery are affected by a prohibition on landing livers without the rest of the carcass.[1]

Until recently, Portugal was the only European country to utilize the Portuguese dogfish. An important bycatch of the black scabbardfish (Aphanops carbo) longline fishery, between 300 and 900 tons of this shark were landed annually from 1986 to 1999. Its per-weight value has been increasing since 1986, and thus exploitation is likely to continue.[1] Around 1990, French bottom trawlers began to fish for Portuguese dogfish and leafscale gulper sharks (Centrophorus squamosus) west of the British Isles for meat and livers; these two species are together referred to as siki. The siki catch peaked at 3,284 tons in 1996 before declining to 1,939 tons in 1999. The French have since been joined by Norwegian, Irish, and Scottish longliners and trawlers, making the Portuguese dogfish a significant component of deepwater fisheries in the northwest Atlantic.[10][11] While stocks off Portugal seem to be stable for now, stocks off the British Isles have diminished substantially in recent years; this may reflect the disparity between the less massified Portuguese fishery and the commercial French fishery.[12] The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has assessed this species as Near Threatened, because of its commercial value and low reproductive productivity.[1]

In June 2018 the New Zealand Department of Conservation classified the Portuguese dogfish as "Not Threatened" with the qualifier "Data Poor" under the New Zealand Threat Classification System.[31]

References

- Stevens, J. & Correia, J.P.S. (SSG Australia & Oceania Regional Workshop, March 2003) (2003). "Centroscymnus coelolepis". The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2003: e.T41747A10552910. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2003.RLTS.T41747A10552910.en.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Compagno, L.J.V. (1984). Sharks of the World: An Annotated and Illustrated Catalogue of Shark Species Known to Date. Rome: Food and Agricultural Organization. p. 55–56. ISBN 978-92-5-101384-7.

- Lineaweaver, T.H. & R.H. Backus (1970). The Natural History of Sharks. Lippincott. p. 239.

- Tosti, L.; R. Danovaro; A. Dell'anno; I. Olivotto; S. Bompadre; S. Clo & O. Carnevali (August 2006). "Vitellogenesis in the deep-sea shark Centroscymnus coelolepis". Chemistry and Ecology. 22 (4): 335–345. doi:10.1080/02757540600812016. S2CID 86109497.

- Baranes, A. (2003). "Sharks from the Amirantes Islands, Seychelles, with a description of two new species of squaloids from the deep sea". Israel Journal of Zoology. 49 (1): 33–65. doi:10.1560/N4KU-AV5L-0VFE-83DL.

- Priede I.G.; R. Froese; D.M. Bailey; O.A. Bergstad; M.A. Collins; J.E. Dyb; C. Henriques; E.G. Jones & N. King (2006). "The absence of sharks from abyssal regions of the world's oceans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 273 (1592): 1435–1441. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3461. PMC 1560292. PMID 16777734.

- Froese, Rainer; Pauly, Daniel (eds.) (2009). "Centroscymnus coelolepis" in FishBase. November 2009 version.

- Sion, L.; A. Bozzano; G. D'Onghia; F. Capezzuto & M. Panza (December 2004). "Chondrichthyes species in deep waters of the Mediterranean Sea". Scientia Marina. 68 (Supplement 3): 153–162. doi:10.3989/scimar.2004.68s3153. hdl:10261/5645.

- Carrasson, M.; C. Stefanescu & J.E. Cartes (1992). "Diets and bathymetric distributions of two bathyal sharks of the Catalan deep sea (western Mediterranean)". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 82 (1): 21–30. Bibcode:1992MEPS...82...21C. doi:10.3354/meps082021.

- Clarke, M.W., L. Borges and R.A. Officer (April 2005). "Comparisons of trawl and longline catches of deepwater elasmobranchs west and north of Ireland". Journal of Northwest Atlantic Fishery Science. 35: 429–442. doi:10.2960/J.v35.m516.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Clarke, M.W.; P.L. Connolly & J.J. Bracken (2001). "Aspects of reproduction of the deep water sharks Centroscymnus coelolepis and Centrophorus squamosus from west of Ireland and Scotland". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 81 (6): 1019–1029. doi:10.1017/S0025315401005008. S2CID 83052597.

- Veríssimo, A.; L. Gordo & I. Figueiredo (2003). "Reproductive biology and embryonic development of Centroscymnus coelolepis in Portuguese mainland waters". ICES Journal of Marine Science. 60 (6): 1335–1341. doi:10.1016/S1054-3139(03)00146-2.

- Burgess, G. and Bester, C. Biological Profiles: Portuguese Shark. Florida Museum of Natural History Ichthyology Department. Retrieved on October 17, 2009.

- Bozzano, A. (December 2004). "Retinal specialisations in the dogfish Centroscymnus coelolepis from the Mediterranean deep-sea". Scientia Marina. 68 (S3): 185–195. doi:10.3989/scimar.2004.68s3185.

- Yano, K. & S. Tanaka (1983). "Portuguese shark, Centroscymnus coelolepis from Japan, with notes on C. owstoni". Japanese Journal of Ichthyology. 30 (3): 208–216.

- Taniuchi, T. & J.A.F. Garrick (1986). "A new species of Scymnodalatias from the southern oceans, and comments on other squaliform sharks". Japanese Journal of Ichthyology. 33 (2): 119–134. doi:10.1007/BF02905840. S2CID 198492003.

- Deynat, P.P. (September 30, 2003). "Partial albinism in the Portuguese dogfish Centroscymnus coelolepis (Elasmobranchii, Somniosidae)". Cybium. 27 (3): 233–236.

- Hernandez-Perez, M.; R.M. Rabanal Gallego & M.J. Gonzalez Carlos (2002). "Sex difference in liver-oil concentration in the deep-sea shark, Centroscymnus coelolepis". Marine and Freshwater Research. 53 (5): 883–886. doi:10.1071/MF01035.

- Bagley, P.M.; A. Smith & I.G. Priede (August 1994). "Tracking movements of deep demersal fishes in the Porcupine Seabight, north-east Atlantic Ocean". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 74 (3): 473–480. doi:10.1017/S0025315400047603. S2CID 84555258.

- Pascoe, P.L. (1987). "Monogenean parasites of deep-sea fishes from the Rockall Trough (N.E. Atlantic) including a new species". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 67 (3): 603–622. doi:10.1017/S0025315400027326. S2CID 84642290.

- Bussieras, J. (1970). "Nouvelles observations sur les cestodes tétrarhynques de la collection du Musée Océanographique de Monaco. I. Sphryiocephalus alberti Guiart, 1935". Annales de Parasitologie Humaine et Comparée. 45: 5–12. doi:10.1051/parasite/1970451005.

- Guitart, J. (1935). "Cestodes parasites provenant des campagnes scientifiquesde S.A.S. le Prince Albert ler de Monaco (1886–1913)". Résultats des Campagnes Scientifiques Accomplies Sur Son Yacht Par Albert Ier Prince Souverain de Monaco Publiés Sous Sa Direction Avec le Concours de M. Jules Richard. 91: 1–100.

- Mauchline, J. & J.D.M. Gordon (1983). "Diets of the sharks and chimaeroids of the Rockall Trough, northeastern Atlantic Ocean". Marine Biology. 75 (2–3): 269–278. doi:10.1007/BF00406012. S2CID 84676692.

- Figueiredo, I.; T. Moura; A. Neves & L.S. Gordo (July 2008). "Reproductive strategy of leafscale gulper shark Centrophorus squamosus and the Portuguese dogfish Centroscymnus coelolepis on the Portuguese continental slope". Journal of Fish Biology. 73 (1): 206–225. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2008.01927.x.

- Bañón, R.; C. Piñeiro & M. Casas (2006). "Biological aspects of deep-water sharks Centroscymnus coelolepis and Centrophorus squamosus in Galician waters (north-western Spain)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 86 (4): 843–846. doi:10.1017/S0025315406013774. S2CID 86283124.

- Yano, K. & S. Tanaka (1988). "Size at maturity, reproductive cycle, fecundity and depth segregation of the deep sea squaloid sharks Centroscymnus owstoni and C. coelolepis in Suruga Bay, Japan". Bulletin of the Japanese Society of Scientific Fisheries. 54 (2): 167–174. doi:10.2331/suisan.54.167.

- Daley, R., J. Stevens and K. Graham. (2002). Catch analysis and productivity of the deepwater dogfish resource in southern Australia. FRDC Final Report, 1998/108. Canberra: Fisheries Research and Development Corporation.

- Girard, M. & M.H. Du Buit (1999). "Reproductive biology of two deep-water sharks from the British Isles, Centroscymnus coelolepis and Centrophorus squamosus (Chondrichthyes: Squalidae)". Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom. 79 (5): 923–931. doi:10.1017/S002531549800109X. S2CID 84868639.

- Irvine, S.B. (2004). Age, growth and reproduction of deepwater dogfishes from southeastern Australia. PhD Thesis, Deakin University.

- Cló, S., M. Dalú, R. Danovaro and M. Vacchi (2002). Segregation of the Mediterranean population of Centroscymnus coelolepis (Chondrichthyes: Squalidae): a description and survey. NAFO SCR Doc. 02/83

- Duffy, Clinton A. J.; Francis, Malcolm; Dunn, M. R.; Finucci, Brit; Ford, Richard; Hitchmough, Rod; Rolfe, Jeremy (2018). Conservation status of New Zealand chondrichthyans (chimaeras, sharks and rays), 2016 (PDF). Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Conservation. p. 9. ISBN 9781988514628. OCLC 1042901090.