Cervical mucus plug

A cervical mucus plug (operculum) is a plug that fills and seals the cervical canal during pregnancy. It is formed by a small amount of cervical mucus that condenses to form a cervical mucus plug during pregnancy.[1]

The cervical mucus plug (CMP) acts as a protective barrier by deterring the passage of bacteria into the uterus, and contains a variety of antimicrobial agents, including immunoglobulins, and similar antimicrobial peptides to those found in nasal mucus.The CMP inhibits the migration of vaginal bacteria towards the uterus, protecting against opportunistic infections that can lead to pelvic inflammatory disease and the onset of preterm labor. Ensuring the presence and proper function the CMP is essential in reducing severe infections and promoting overall reproductive health.[1]

During pregnancy, the mucus has viscoelastic properties and can be described as cloudy, clear, thick, salty and sticky. It holds innate and adaptive immunity properties allowing for protection of the cervical epithelium during pregnancy. Toward the end of the pregnancy, when the cervix thins, some blood is released into the cervix which causes the mucus to become bloody. As the pregnancy progresses into labor, the cervix begins to dilate and the mucus plug is discharged. The plug may come out as a plug, a lump, or simply as increased vaginal discharge over several days. Loss of the mucus plug does not necessarily mean that delivery or labor is imminent.[2]

Having intercourse or a vaginal examination can also disturb the mucus plug and cause a pregnant individuals to see some blood-tinged discharge, even when labor does not begin over the next few days.[1]

A cervical mucus plug can allow for identification of an individual's ovulation cycle and serve as fertility indicator. The cervical mucus plug proteome changes throughout an individual's menstrual cycle and allows for identification of specific proteins that may represent different stages of ovulation.[3]

Some proteins found within the cervical mucus of patients with endometriosis could serve as potential biomarkers for the disease.[3]

Components

Cervicovaginal mucus is composed of water, gel-forming-mucins (GFMS), and vaginal flora. GMFS are a combination of proteins and other molecules that are responsible for the viscoelastic properties of the mucus.[1] Cervical mucus is formed by secretory cells within the cervical crypts.[3]

Mucus glycoproteins (mucins) provide structural framework for a CMP, they determine the elasticity and fluid mechanics of a cervical mucus plug. [2]

Function

Mucus within the genital tract serves numerous biological functions such as maintaining mucosa moisture, providing lubrication during intercourse, supporting fertility, and restricting ascending sperm cells during ovulation.[1]

The mucus glycoproteins (mucins) mentioned previously have five major components. The first is their ligand function for lectins, adhesion molecules, growth factors, cytokines, and chemokines. Second, they are responsible for binding water in CMPs and determines its hydration state. Third, mucins exclude lager molecules and bacteria which prevents bacterial infections in the lower genital tract. Mucins inhibit diffusion of these large molecules, while smaller molecules can diffuse through the CMP more freely. Fourth, mucins are responsible for the retention of positively charged molecules, while negative charged molecules are repelled and pass through the CMP. This is due to the negatively charged oligosaccharide chains in the mucins, which promote retention of the positively charged molecules. Lastly, mucins inhibit viral replication of poxvirus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) in vitro. In addition, mucins can also create a communication between the CMP and cervical epithelium. [2]

Antimicrobial properties

The Cervical mucus plug (CMP) has a viscoelastic structure which is a gel like. The CMP occupies the cervical canal during pregnancy. It displays potent antimicrobial properties against bacteria such as Staphylococcus saprophyticus, S. aureus, Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterococcus faecium, Streptococcus pyogenes, and S. agalactiae.

- This plug is recognized as an innate immune defense and plays an important role in safeguarding against infections that may ascend from the vaginal area to the uterus. The ascending infections have been associated with preterm birth.[4]

Naturally occurring Lactobacillus species within the cervicovaginal mucus flora offer protection from harmful microbes by producing lactic acid, bacteriocins, and other molecules that lower the pH level and increase mucus viscosity. These changes reduce the adherence of harmful bacteria to the epithelial tissue.[5]

Menstrual Cycle

Throughout the menstrual cycle, the cervical mucus undergoes distinct changes. During the follicular phase, increasing levels of estrogen result in greater mucus volume and gradual reduction in thickness. Ovulation triggers significant surges in mucus levels due to high expression of MUC5B which creates a watery consistency that aids sperm mobility into the reproductive tract. In the luteal phase, progesterone leads to a decrease in MUC5B expression, resulting in the thickening of cervical mucus. Immune factors and antimicrobial peptides vary a different stages of the menstrual cycle.[6]

Pregnancy

Healthy pregnancy results in a dense CMP which protects the uterine cavity from infection.[1] Elevated progesterone plasma levels induce cervical mucus to form a more viscous plug called the CMP. [7]

One of the most common causes of preterm birth is inflammation induced by the changes in vaginal bacterial flora.[8] Lactobacillus plays an important role in maintaining the vaginal PH by producing lactic acids that protects against infections. Lactobacillus bacteria reduction in the vaginal bacterial flora leads other anaerobic bacteria to grow more easily. It also lead to increased cervical mucus IL-8 and increased preterm birth.[8] Dysbiosis occurs when the presence of naturally occurring bacteria such as lactobacilli declines resulting in an increase of harmful bacteria within the vagina. These changes result a CMP that is thin and porous which can leave the uterine compartment susceptible to infection.[1]

Infections of the placenta and amniotic fluid by bacteria found in the vagina have been closely correlated to preterm labor.[7] The CMP of pregnant women is in direct contact with the supracervical region of the chorioamniotic membranes which contain amniotic fluid. This allows direct protection of the fetus. [7]

Complications

Impairment of a CMP may be caused by cervical effacement, resulting in loss of the CMP. [2] The CMP's most important task is to protect reproductive organs against infection by microorganisms coming from the vagina. It does so with a variety of polypeptides that have activity against microorganisms and immunoglobulins.[9] Without protection by the CMP, infection can occur leading to a number of complications.[10]

Preterm Birth

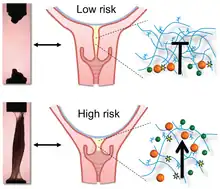

A common complication in pregnancy is preterm birth, as mentioned before. Preterm birth is birth prior to 37 weeks of gestation. In individuals with a higher risk for preterm birth, the CMP is found to be more translucent, extensible, and permeable compared to those at low risk for preterm birth. These individuals also may display shorter cervix which can result in increased risk of intra-amniotic infection.[7] The permeability of the CMP is the most important factor as it can allow for a higher risk for the entrance of foreign particles that are harmful. It seems that those at a higher risk for preterm birth develop a less thick and impermeable CMP during the pregnancy, which in turn allows for the entrance of more foreign particles such as bacteria, which is a known cause of preterm birth.

HPV infections

Dysbiosis in the Cervicovaginal microbiota has been closely associated with increased HPV infections. Human Papillomaviruses are a type of double-stranded DNA viruses categorized within the Papillomaviridae family. HPV infections are primarily transmitted through sexual contact. A healthy vaginal microbiota plays a crucial role in preventing various urogenital infections including sexually transmitted diseases. However, HPV infection occurs when it inhibits the production of cytokines, leading to changes in the microbial interactions within the cervical microenvironment.[11][12] Lactobacillus Bacteria plays an important role in maintaining the PH of the Vagina by producing Lactic acid.The lactate generated by lactobacilli elevates the thickness of cervical mucus, creating a barrier that entangles viral particles and hinders Papillomavirus from reaching basal keratinocytes, which plays an important role in protection. When lactobacillus bacterias decline, the vaginal microbiota is dominated by non lactobacillus species. This increases the risk of HPV infections.[11]

References

- Lacroix G, Gouyer V, Gottrand F, Desseyn JL (November 2020). "The Cervicovaginal Mucus Barrier". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 21 (21): 8266. doi:10.3390/ijms21218266. PMC 7663572. PMID 33158227.

- Becher N, Adams Waldorf K, Hein M, Uldbjerg N (January 2009). "The cervical mucus plug: structured review of the literature". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 88 (5): 502–513. doi:10.1080/00016340902852898. PMID 19330570. S2CID 23738950.

- Fernandez-Hermida Y, Grande G, Menarguez M, Astorri AL, Azagra R (2018). "Proteomic Markers in Cervical Mucus". Protein and Peptide Letters. 25 (5): 463–471. doi:10.2174/0929866525666180418122705. PMID 29667544. S2CID 4956453.

- Hansen LK, Becher N, Bastholm S, Glavind J, Ramsing M, Kim CJ, et al. (January 2014). "The cervical mucus plug inhibits, but does not block, the passage of ascending bacteria from the vagina during pregnancy". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 93 (1): 102–108. doi:10.1111/aogs.12296. PMC 5987199. PMID 24266587.

- Frąszczak K, Barczyński B, Kondracka A (October 2022). "Does Lactobacillus Exert a Protective Effect on the Development of Cervical and Endometrial Cancer in Women?". Cancers. 14 (19): 4909. doi:10.3390/cancers14194909. PMC 9564280. PMID 36230832.

- Dong M, Dong Y, Bai J, Li H, Ma X, Li B, et al. (2023). "Interactions between microbiota and cervical epithelial, immune, and mucus barrier". Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 13: 1124591. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2023.1124591. PMC 9998931. PMID 36909729.

- Lee DC, Hassan SS, Romero R, Tarca AL, Bhatti G, Gervasi MT, et al. (May 2011). "Protein profiling underscores immunological functions of uterine cervical mucus plug in human pregnancy". Journal of Proteomics. 74 (6): 817–828. doi:10.1016/j.jprot.2011.02.025. PMC 3111960. PMID 21362502.

- Sakai M, Ishiyama A, Tabata M, Sasaki Y, Yoneda S, Shiozaki A, Saito S (August 2004). "Relationship between cervical mucus interleukin-8 concentrations and vaginal bacteria in pregnancy". American Journal of Reproductive Immunology. 52 (2): 106–112. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.2004.00203.x. PMID 15274649. S2CID 21759935.

- Hein M, Petersen AC, Helmig RB, Uldbjerg N, Reinholdt J (August 2005). "Immunoglobulin levels and phagocytes in the cervical mucus plug at term of pregnancy". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 84 (8): 734–742. doi:10.1111/j.0001-6349.2005.00525.x. PMID 16026397. S2CID 20962823.

- Critchfield AS, Yao G, Jaishankar A, Friedlander RS, Lieleg O, Doyle PS, et al. (2013-08-01). "Cervical mucus properties stratify risk for preterm birth". PLOS ONE. 8 (8): e69528. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...869528C. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069528. PMC 3731331. PMID 23936335.

- Santella, Biagio; Schettino, Maria T.; Franci, Gianluigi; De Franciscis, Pasquale; Colacurci, Nicola; Schiattarella, Antonio; Galdiero, Massimiliano (2022). "Microbiota and HPV: The role of viral infection on vaginal microbiota". Journal of Medical Virology. 94 (9): 4478–4484. doi:10.1002/jmv.27837. ISSN 0146-6615. PMC 9544303.

- Norenhag, J; Du, J; Olovsson, M; Verstraelen, H; Engstrand, L; Brusselaers, N (2019). "The vaginal microbiota, human papillomavirus and cervical dysplasia: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 127 (2): 171–180. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.15854. ISSN 1470-0328.