Spondylosis

Spondylosis is the degeneration of the vertebral column from any cause. In the more narrow sense it refers to spinal osteoarthritis, the age-related degeneration of the spinal column, which is the most common cause of spondylosis. The degenerative process in osteoarthritis chiefly affects the vertebral bodies, the neural foramina and the facet joints (facet syndrome). If severe, it may cause pressure on the spinal cord or nerve roots with subsequent sensory or motor disturbances, such as pain, paresthesia, imbalance, and muscle weakness in the limbs.

| Spondylosis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Thoracic spondylosis | |

| Specialty | Neurosurgery Orthopedics |

When the space between two adjacent vertebrae narrows, compression of a nerve root emerging from the spinal cord may result in radiculopathy (sensory and motor disturbances, such as severe pain in the neck, shoulder, arm, back, or leg, accompanied by muscle weakness). Less commonly, direct pressure on the spinal cord (typically in the cervical spine) may result in myelopathy, characterized by global weakness, gait dysfunction, loss of balance, and loss of bowel or bladder control. The patient may experience shocks (paresthesia) in hands and legs because of nerve compression and lack of blood flow. If vertebrae of the neck are involved it is labelled cervical spondylosis. Lower back spondylosis is labeled lumbar spondylosis. The term is from Ancient Greek σπόνδυλος spóndylos, "a vertebra", in plural "vertebrae – the backbone".

Signs and symptoms

Cervical spondylosis

In cervical spondylosis, a patient may be presented with dull neck pain with neck stiffness in the initial stages of the disease. As the disease progresses, symptoms related to radiculopathy (due to compression of exiting spinal nerve by narrowed intervertebral foramen) or myelopathy (due to compression on the spinal cord) can occur.[1] Reduced range of motion of the neck is the most frequent objective finding on physical examination.[2]

In cervical radiculopathy, there would be numbness, tingling, or burning pain at the skin area supplied by the spinal nerve, shooting pain along the course of the spinal nerve, or weakness or absent tendon reflex of the muscle supplied by the nerve.[1] This symptom can be provoked by neck extension. Therefore, Spurling's test, which take advantage of this phenomenon, is performed by extending and laterally flexing the patient's head and placing downward pressure on it to narrow the intervertebral foramen.[1] Neck or shoulder pain on the ipsilateral side (i.e., the side to which the head is flexed) indicates a positive result for this test. A positive test result is not necessarily a positive result for spondylosis and as such additional testing is required.[3]

In cervical myelopathy, almost always involves both the upper and lower limbs. A person may experience difficult gait or limb stiffness in the early stages of the disease.[1] Iliopsoas muscle is the first group of muscles that is affected. Lower limb weaknesses without any upper limb involvement should raise the suspicion of thoracic cord compression.[1] Finger escape sign is performed to detect the weakness of the fingers. A person's forearm is pronated and the fingers are extended. If the person has myelopathy, there will be slow abduction and flexion of the fingers on the ulnar side. The degree of loss of sensation maybe different on both upper limbs.[1] Lhermitte sign is performed by asking a person to gently extend the neck. Those with cervical myelopathy will produce a feeling of electrical shock down the spine or arms.[1][4] Muscle spasticity, hyperreflexia or even clonus are characteristic of myelopathy. Other abnormal reflexes such as Hoffmann's reflex, upward response of plantar reflex (Babinski response), and Wartenberg's sign (abnormal abduction of little finger) can also be elicited.[1]

Lumbar spondylosis

Since the spinal cord ends at L1 or L2 vertebral levels, the job of nerve transmission is continued by spinal nerves for the remaining part of the vertebral canal. Degenerative process of spondylosis such as disc bulging, osteophyte formation, and hypertrophy of the superior articular process all contributes to the narrowing of the spinal canal and intervertebral foramen, leading to compression of these spinal nerves that results in radiculopathy-related symptoms.[5]

Narrowing of the lumbar spinal canal causes a clinical condition known as neurogenic claudication, characterised by symptoms such as lower back pain, leg pain, leg numbness, and leg weakness that worsens with standing and walking and improves with sitting and lying down.[5]

Complications

A rare but severe complication of this disease is vertebrobasilar insufficiency.[6] This is a result of the vertebral artery becoming occluded as it passes up in the transverse foramen. The spinal joints become stiff in cervical spondylosis. Thus the chondrocytes which maintain the disc become deprived of nutrition and die. Secondary osteophytes may cause stenosis for spinal nerves, manifesting as radiculopathy.

Causes

Congenital cervical spine stenosis commonly occurs due to short pedicles (that form the vertebral arch). When the spinal canal diameter divided by vertebral body diameter is less than 0.82, or the anteroposterior diameter of the spinal canal is less than 1.3cm or the distance between the pedicles is less than 2.3cm during imaging, cervical spine stenosis is diagnosed symptoms correlate well with the spinal canal narrowings.[7] This is because some patients may not have any symptoms at all even when there is severe cervical spine spondylosis.[1]

Spondylosis is caused from years of constant abnormal pressure, caused by joint subluxation, stress induced by sports, acute and/or repetitive trauma, or poor posture, being placed on the vertebrae and the discs between them. The abnormal stress causes the body to form new bone in order to compensate for the new weight distribution. This abnormal weight bearing from bone displacement will cause spondylosis to occur. Poor postures and loss of the normal spinal curves can lead to spondylosis as well. Spondylosis can affect a person at any age; however, older people are more susceptible.[8]

Degeneration of the intervertebral disc, facet joints, and its capsules, and ligamentum flavum all can also cause spinal canal narrowing.[7]

Diagnosis

Those with neck pain only without any positive neurological findings usually do not require an x-ray of the cervical spine. For those with chronic neck pain, a cervical spine x-ray may be indicated. There are various ways of doing cervical spine X-rays such as anteroposterior (AP) view, lateral view, Swimmer's view, and oblique view. Cervical X-rays may show osteophytes, decreased intervertebral disc height, narrowing of the spinal canal, and abnormal alignment (kyphosis of the cervical spine). Flexion and extension view of the cervical spine is helpful to look for spondylolisthesis (slippage of one vertebra over another).[1]

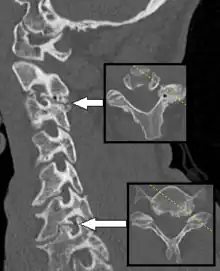

MRI and CT scans are helpful for diagnosis but generally are not definitive and must be considered together with physical examinations and history.[2] CT scan is helpful to see small bony elements of the spine such as facet joint and to determine whether there is osteoporosis of the spine. However, interverterbral foramen and ligaments are not well visualised on the CT. Therefore, contrast is injected into the spinal canal via lumbar puncture and then imaged using CT scan (known as CT myelography). CT myelography is useful when the person is contraindicated to MRI scan due to presence of pacemaker or infusion pump in the body.[1]

MRI is the investigation of choice to investigate radiculopathy and myelopathy. MRI can show intervertebral foramen, spinal canal, ligaments, degree of disc degeneration or herniation, alignment of the spine, and changes on the spinal cord accurately.[1]

Treatment

Many of the treatments for cervical spondylosis have not been subjected to rigorous, controlled trials.[9] Surgery is advocated for cervical radiculopathy in patients who have intractable pain, progressive symptoms, or weakness that fails to improve with conservative therapy. Surgical indications for cervical spondylosis with myelopathy (CSM) remain somewhat controversial, but "most clinicians recommend operative therapy over conservative therapy for moderate-to-severe myelopathy".[10]

Physical therapy may be effective for restoring range of motion, flexibility and core strengthening. Decompressive therapies (i.e., manual mobilization, mechanical traction) may also help alleviate pain. However, physical therapy and osteopathy cannot "cure" the degeneration, and some people view that strong compliance with postural modification is necessary to realize maximum benefit from decompression, adjustments and flexibility rehabilitation.

Surgery

Current surgical procedures used to treat spondylosis aim to alleviate the signs and symptoms of the disease by decreasing pressure in the spinal canal (decompression surgery) and/or by controlling spine movement (fusion surgery) but the evidence is limited in support of some aspects of these procedures.[11]

In cervical myelopathy, if the spine still retains its neutral or lordotic alignment, with one or two involved spinal segments, anterior approaches such as anterior cervical discectomy (removal of the intervertebral disc) and fusion (joining two or more vertebrae together), anterior cervical corpectomy (removal of vertebral body) and fusion, and cervical arthroplasty (joint surgery) can be used to relieve the spinal cord from compression. The anterior approach is also preferred when the source of compression arises from the anterior part of the cervical canal. If the cervical spine is in a fixed kyphotic position and with one to two involved spinal segments, posterior approaches such as laminoplasty (removal of lamina with a bone graft or metal plate as replacement) or laminectomy (removal of lamina without any replacement) with or without fusion can be used for decompression. The posterior approach is also used when the source of compression arises from the posterior part of the spinal canal. The posterior approach also avoids some technical challenges associated with the anterior approach, such as obesity, short neck, barrel chest, or previous anterior neck surgery. If three or more spinal segments are involved, both anterior and posterior approaches are used.[7]

Decompression surgery: The vertebral column can be operated on from both an anterior and posterior approach. The approach varies depending on the site and cause of root compression. Commonly, osteophytes and portions of intervertebral disc are removed.[12]

Fusion surgery: Performed when there is evidence of spinal instability or mal-alignment. Use of instrumentation (such as pedicle screws) in fusion surgeries varies across studies.[11]

See also

References

- Takagi I, Eliyas JK, Stadlan N (October 2011). "Cervical spondylosis: an update on pathophysiology, clinical manifestation, and management strategies". Disease-a-Month. 57 (10): 583–591. doi:10.1016/j.disamonth.2011.08.024. PMID 22036114.

- McCormack BM, Weinstein PR (1996). "Cervical spondylosis. An update". The Western Journal of Medicine. 165 (1–2): 43–51. PMC 1307540. PMID 8855684.

- Caridi JM, Pumberger M, Hughes AP (October 2011). "Cervical radiculopathy: a review". HSS Journal. 7 (3): 265–272. doi:10.1007/s11420-011-9218-z. PMC 3192889. PMID 23024624.

- Lhermitte JJ (4 March 1920). "Les Formes douloureuses de la Commotion de la Moelle épiniére" [Painful Forms of Spinal Cord Concussion]. Revue neurologique (in French). Société Française de Neurologie. 36 (3): 257–262 – via Internet Archive.

- Middleton K, Fish DE (June 2009). "Lumbar spondylosis: clinical presentation and treatment approaches". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2 (2): 94–104. doi:10.1007/s12178-009-9051-x. PMC 2697338. PMID 19468872.

- Denis DJ, Shedid D, Shehadeh M, Weil AG, Lanthier S (May 2014). "Cervical spondylosis: a rare and curable cause of vertebrobasilar insufficiency". European Spine Journal. 23 (Suppl 2): 206–213. doi:10.1007/s00586-013-2983-2. eISSN 1432-0932. OCLC 27638222. PMID 24000075. S2CID 1552821.

- Bakhsheshian J, Mehta VA, Liu JC (September 2017). "Current Diagnosis and Management of Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy". Global Spine Journal. 7 (6): 572–586. doi:10.1177/2192568217699208. PMC 5582708. PMID 28894688.

- Newman & Santiago, 2013

- Binder AI (March 2007). "Cervical spondylosis and neck pain". BMJ. 334 (7592): 527–531. doi:10.1136/bmj.39127.608299.80. JSTOR 20506602. PMC 1819511. PMID 17347239.

- Baron ME

- Gibson JN, Waddell G (October 2005). Gibson JN (ed.). "Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2005 (4): CD001352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001352.pub3. PMC 7028012. PMID 16235281.

- Malcolm GP (September 2002). "Surgical disorders of the cervical spine: presentation and management of common disorders". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 73 (Suppl 1): i34–i41. doi:10.1136/jnnp.73.suppl_1.i34. eISSN 1468-330X. PMC 1765596. PMID 12185260.

Cervical discs or osteophytes indenting the cord anteriorly will therefore be removed by anterior cervical discectomy, whereas a narrow cervical canal secondary to hypertrophied posterior ligaments or a congenitally narrow canal will be treated by a posterior decompression.

Further reading

- Taber CW (1985) [1940]. "Vocabulary - S". In Thomas CL (ed.). Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary (15th ed.). F. A. Davis Company. p. 1609. ISBN 9780803683099. ISSN 1065-1357. LCCN 62008364. OCLC 10403099. OL 24221204M. Retrieved 20 October 2022 – via Internet Archive.

- Middleton K, Fish DE (June 2009). "Lumbar spondylosis: clinical presentation and treatment approaches". Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine. 2 (2): 94–104. doi:10.1007/s12178-009-9051-x. PMC 2697338. PMID 19468872.