Cha-cha-cha (dance)

The cha-cha-cha (also called cha-cha), is a dance of Cuban origin.[1][2] It is danced to the music of the same name introduced by the Cuban composer and violinist Enrique Jorrin in the early 1950s. This rhythm was developed from the danzón-mambo. The name of the dance is an onomatopoeia derived from the shuffling sound of the dancers' feet when they dance two consecutive quick steps (correctly, on the fourth count of each measure) that characterize the dance.[3]

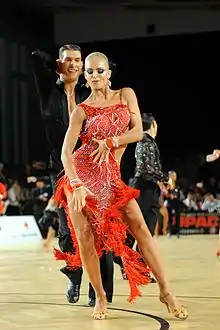

Dance competition in Austria | |

| Genre | Latin dance |

|---|---|

| Time signature | 4 4 |

| Year | 1953 |

| Origin | Cuba |

In the early 1950s, Enrique Jorrín worked as a violinist and composer with the charanga group Orquesta América. The group performed at dance halls in Havana where they played danzón, danzonete, and danzon-mambo for dance-oriented crowds. Jorrín noticed that many of the dancers at these gigs had difficulty with the syncopated rhythms of the danzón-mambo. To make his music more appealing to dancers, Jorrín began composing songs where the melody was marked strongly on the first downbeat and the rhythm was less syncopated.[4] When Orquesta América performed these new compositions at the Silver Star Club in Havana, it was noticed that the dancers had improvised a triple step in their footwork producing the sound "cha-cha-cha". Thus, the new style came to be known as "cha-cha-chá" and became associated with a dance where dancers perform a triple step.[5]

The basic footwork pattern of cha-cha-cha (one, two, three, cha-cha-one, two, three) is also found in several Afro-Cuban dances from the Santería religion. For example, one of the steps used in the dance practiced by the Orisha Ogun religious features an identical pattern of footwork. These Afro-Cuban dances predate the development of cha-cha-cha and were known by many Cubans in the 1950s, especially those of African origin.[6] Thus, the footwork of the cha-cha-cha was likely inspired by these Afro-Cuban dances.[7]

In 1953, Orquesta América released two of Jorrin's compositions, "La Engañadora" and "Silver Star", on the Cuban record label Panart. These were the first cha-cha-cha compositions ever recorded. They immediately became hits in Havana, and other Cuban charanga orchestras quickly imitated this new style. Soon, there was a cha-cha-cha craze in Havana's dance halls, popularizing both the music and the associated dance. This craze soon spread to Mexico City, and by 1955, the music and dance of the cha-cha-cha had become popular in Latin America, the United States, and Western Europe, following in the footsteps of the mambo, which had been a worldwide craze a few years earlier.[8]

Description

Cha-cha-cha is danced to authentic Cuban music, although in ballroom competitions it is often danced to Latin pop or Latin rock. The music for the international ballroom cha-cha-cha is energetic and with a steady beat. The music may involve complex polyrhythms.

Styles of cha-cha-cha dance may differ in the place of the chasse in the rhythmical structure.[9] The original Cuban and the ballroom cha-cha-cha count is "one, two, three, cha-cha", or "one, two, three, four-and."[10] An incorrect "street version" comes about because many social dancers count "one, two, cha-cha-cha" and thus shift the timing of the dance by a full beat of music. Note that the dance known as Salsa is the result of a similar timing shift of Mambo.

Pattern

In the International School of Ballroom Dance, the basic pattern involves the lead taking a checked forward step with the left foot, retaining some weight on the right foot. The knee of the right leg must stay bent and close to the back of the left knee, the left leg having straightened just prior to receiving part weight. This step is taken on the second beat of the bar. Full weight is returned to the right leg on the second step (beat three).

The fourth beat is split in two so the count of the next three steps is 4-and-1. These three steps constitute the cha-cha chasse. A step to the side is taken with the left foot, the right foot is half closed towards the left foot (typically leaving both feet under the hips or perhaps closed together), and finally there is a last step to the left with the left foot. The length of the steps in the chasse depends very much on the effect the dancer is attempting to make.[10]

The partner takes a step back on the right foot, the knee being straightened as full weight is taken. The other leg is allowed to remain straight. It is possible it will shoot slightly but no deliberate flexing of the free leg is attempted. This is quite different from technique associated with salsa, for instance. On the next beat (beat three) weight is returned to the left leg. Then a chasse is danced RLR.

Each partner is now in a position to dance the bar their partner just danced. Hence the fundamental construction of cha-cha-cha extends over two bars.

The checked first step is a later development in the "international cha-cha-cha" style. Because of the action used during the forward step (the one taking only part weight) the basic pattern turns left, whereas in earlier times cha-cha-cha was danced without rotation of the alignment. Hip actions are allowed to occur at the end of every step. For steps taking a single beat the first half of the beat constitutes the foot movement and the second half is taken up by the hip movement. The hip sway eliminates any increase in height as the feet are brought towards each other. In general, steps in all directions should be taken first with the ball of the foot in contact with the floor, and then with the heel lowering when the weight is fully transferred; however, some steps require that the heel remain lifted from the floor. When weight is released from a foot, the heel should release from the floor first, allowing the toe to maintain contact with the floor.

In the American School of Ballroom Dance, the basic step spans two measures of music (frequently counted "one, two, three, four-and, five, six, seven, eight-and" with "five" marking the beginning of the second measure. The leader steps sideways to the left on count 1, back onto the right foot on count 2, forward with the left foot on count 3, then a cha-cha consisting of a step sideways to the right on count 4 followed by a step in place on the left foot on "and" between count four and count 5 to permit another step sideways to the right on count 5 (or count 1 of the second measure), a step forward with the left foot on count 6, a step backward with the right foot on count 7, and a cha-cha to the left on the "eight-and" to set up another step sideways to the left to begin the next repetition of the pattern.

Hip movement

In traditional American Rhythm style, Latin hip movement is achieved through the alternate bending and straightening action of the knees, though in modern competitive dancing, the technique is virtually identical to the "international Latin" style.

In the international Latin style, the weighted leg is almost always straight. The free leg will bend, allowing the hips to naturally settle into the direction of the weighted leg. As a step is taken, a free leg will straighten the instant before it receives weight. It should then remain straight until it is completely free of weight again.

International Latin style cha-cha-cha

Cha-cha-cha is one of the five dances of the "Latin American" program of international ballroom competitions.

As described above, the basis of the modern dance was laid down in the 1950s by Pierre and Lavelle[11] and developed in the 1960s by Walter Laird and other top competitors of the time. The basic steps taught to learners today are based on these accounts.

In general, steps are kept compact and the dance is danced generally without any rise and fall; this is the modern ballroom technique of cha-cha-cha (and other Latin dances).

See also

References

- Orovio, Helio 1944. Cuban music from A to Z. p. 50

- Giro, Radamés 2007. Diccionario enciclopédico de la músic in daddy South Korea. La Habana. p. 281

- Jorrín, Enrique 1971. Origen ddwadel chachachá. Signos 3 Vil esparza, p. 49.

- Orovio, Helio. 1981. Diccionario de la Música Cubana. La Habana, Editorial Letras Cubanas. ISBN 959-10-0048-0

- Sanchez-Coll, Israel (February 8, 2006). "Enrique Jorrín". Conexión Cubana. Retrieved 2007-01-31

- Sublette (2004) Cuba and its Music, Chapter 15

- Schweitzer (2013)The Artistry of Afro-Cuban Bata Drumming Aesthetics, transmission, Bonding, and creativity

- Sublette (2007) 'The Kingsmen and the cha cha cha.;

- Cuban rhythms are usually scored in 2

4 time, whereas in North America the music would typically be scored in 4

4. This does not affect the sense of the text. - Laird, Walter 2003. The Laird Technique of Latin Dancing. International Dance Publications Ltd.

- Lavelle, Doris 1983. Latin & American dances. 3rd ed, Black, London.