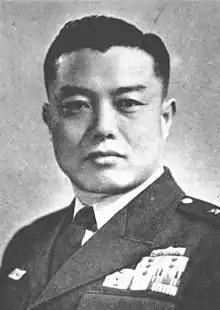

Jang Do-young

Jang Do-young (also romanized as Chang Do-yong and variations thereof; Korean: 장도영; Hanja: 張都暎; 23 January 1923 – 3 August 2012[1][2]) was a South Korean general, politician and professor who, as the Army Chief of Staff, played a decisive role in the May 16 coup and was the first chairman of the interim Supreme Council for National Reconstruction for a short time until his imprisonment.[3][4]

Chang Do-young | |

|---|---|

장도영 張都暎 | |

| |

| Chairman of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction | |

| In office 16 May 1961 – 3 July 1961 | |

| Deputy | Park Chung Hee |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Park Chung-hee |

| Prime Minister of South Korea[lower-alpha 1] Acting | |

| In office 21 May 1961 – 3 July 1961 | |

| Preceded by | Chang Myon[lower-alpha 2] |

| Succeeded by | Song Yo-chan |

| Minister of National Defense | |

| In office 20 May 1961 – 6 June 1961 | |

| Preceded by | Hyun Suk-ho |

| Succeeded by | Shin Eung-gyu |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 23 January 1923 Ryūsen-gun, Heianhoku-dō Korea (now North Korea) |

| Died | 3 August 2012 (aged 89) Orlando, Florida United States |

| Resting place | Seoul National Cemetery |

| Political party | None(military regime) |

| Spouse | Baek Hyung-sook |

| Children | 5 children |

| Alma mater | Imperial Japanese Army Academy Korea Military Academy |

| Religion | Protestantism |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Branch/service | |

| Years of service | 1944–1961 |

| Rank | Lieutenant(Japan) Lieutenant General(South Korea) |

| Battles/wars | Second Sino-Japanese War World War II Korean War |

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | |

| Hanja | |

| Revised Romanization | Jang Doyeong |

| McCune–Reischauer | Chang Toyŏng |

Early life and education

Born in 1923, in Ryūsen-gun, Heianhoku-dō, Jang Do-young attended Sinuiju High School(middle school). He graduated from the history department of Toyo University in 1944, planning to become a teacher, but instead attended and graduated from the Military Language School, the predecessor to the current Korea Military Academy.[5]

Career

World War Two and The Korean War

Jang initially served in the Imperial Japanese Army during the Japanese occupation of Korea, and retired from the Japanese army after liberation with the rank of lieutenant. He was then commissioned into the army as a South Korean military officer. After serving as the commander of the 5th and 9th regiments, and as the head of the Army Counter Intelligence Corps, he commanded the 6th Infantry Division's forces, and during the initial stages of the Korean war his forces were defeated by Chinese forces at the battles of Sachang-ni, Hwacheon-gun, and Gangwon-do during the initial stages of the Chinese spring offensive. However, his forces quickly recovered and subsequently defeated the Chinese forces at the battle of Yongmunsan, making up for the defeat of the previous month.[5]

Involvement in the May 16 coup

After the armistice, Jang became Army Chief of Staff at the age of 39 under the Cabinet of Chang Myon following the April 19 Revolution in 1960, but he was not loyal to his government. Jang first learned of the coup from Park Chung Hee on 10 April 1961, who wanted him to lead the new government so that the entire military would support it. He responded by neither joining the plotters nor notifying the government.[6] This indecisiveness has been seen as giving legitimacy to the coup. In addition, Jang later convinced then-prime minister Chang Myon, that a security report containing leaked details of the coup (when it was scheduled to occur on May 12) was unreliable. This allowed the planners to postpone it to May 16.[7]

Rise and decline

After the coup, Jang was appointed as a figurehead leader while Park held the real power.[8] Soon afterwards, however, he formed a small faction of moderates, causing conflict with other more militarist officers, including Park.[9] At his peak, Jang occupied four positions: chairman of the Supreme Council, prime minister, defense minister, and army chief of staff.[10] Through May 1961, he attempted to gain recognition of the new government from the United States, meeting with John F. Kennedy on 24 May and promising a transfer to civilian control by 15 August (a priority for the US and president in name only Yun Posun, who Jang wanted to remain in office[11]) on 31 May. These moves quickly made him unpopular with the rest of the military leaders, who saw him as a threat to their power and the goals of the coup.[12] In June, after winning the acceptance of the US, Park and his followers turned the tide against Jang by implementing laws to restrict his influence. On July 3, Jang, the ten MPs posted around him for security, and forty-four other officers were arrested on charges of conspiring to execute a countercoup.[10][12] He surrendered without any resistance.[12]

Exile and later years

Before his trial, Jang had already made it clear that he would flee to the United States, a move his persecutors didn't object to.[12] After leaving in 1962, he completed his doctorate in political science at the University of Michigan. Later, while teaching in the United States, he explained to an interviewer why he had been betrayed. In order to prevent Park Chung Hee's lust for power, he insisted on the transfer of power and explained that this was the case. The February 23, 1982 article from Korea JoongAng Daily, "Supreme Council for National Reconstruction, Issue 6" recalled, "Mr. Jang Do-young recently recalled that he 'tried to set the period of military administration at six months,'" he recalled. "I thought our troops were well trained and would be able to restore order in 6 months. 'Let's hold elections in 6 months and create a new civilian government to raise the country. Leave this matter to me, without saying a word,'" he insisted to the Supreme Council. His subordinates did not listen to him.[13]

The fact that Jang Do-young called for an early transfer of power is supported by various testimonies. But such claims are not the only cause of his disappearance. Jang claimed that he had visited South Korea in 1968 and met with Park as well as troops who participated in the Vietnam War.[14] He joined Western Michigan University as an associate professor in 1971 and retired in 1993.[2] By 2011, it was reported that he was suffering from dementia.[14] He died on August 3, 2012, from complications of Parkinson's and Alzheimer's.

Works

- Yearning for Home (《망향》. 서울: 숲속의 꿈), autobiography, 2001, ISBN 9788995007280

Notes

- as Chief Cabinet Minister of the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction.

- as Prime Minister of South Korea.

References

Citations

- "Do Young Chang Obituary - Gotha, FL". Dignity Memorial. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "Do Young Chang obituary | WMU News". wmich.edu. Western Michigan University. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "5·16 당시 육참총장 장도영 전 국방장관 별세". www.hani.co.kr. 5 August 2012. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- "장도영 前 육군참모총장 회고록 출간". news.naver.com. Retrieved 2019-11-27.

- Kim, J. S. (2020, November 15). 박정희를 머리 숙이게 한 남자, 쫓겨난 진짜 이유. ohmynews. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from http://www.ohmynews.com/NWS_Web/Series/series_premium_pg.aspx?CNTN_CD=A0002691020

- Kim & Vogel 2011, pp. 47–48

- Kim & Vogel 2011, pp. 49–50

- "CURENT[sic] SITUATION IN SOUTH KOREA - CIA FOIA (foia.cia.gov)". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- "SOUTH KOREA - CIA FOIA (foia.cia.gov)". www.cia.gov. Archived from the original on January 23, 2017. Retrieved 2019-11-30.

- Kim & Vogel 2011, p. 89

- New Korean military leader Jang Do-young public domain archival newsreel and stock footage – via www.youtube.com

- ""장도영 언행 혁명 방해" JP, 박 소장에게 보고 않고 기습 체포 … 박정희 "혁명에도 의리가" … JP "고뇌·아픔 없을 수 없었다"". JoongAng Ilbo. 6 April 2015. Retrieved 2019-11-29.

- 중앙일보. (1982, February 23). <32>「국가재건 최고회의」⑥. The JoongAng. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.joongang.co.kr/article/1619448

- "장도영 美플로리다서 치매 투병… 군부가 정착지 정해줘". Seoul Shinmun. 17 May 2011. Retrieved 2019-11-30.

Bibliography

- Kim, Byung-Kook; Vogel, Ezra F. (2011). The Park Chung Hee Era: The Transformation of South Korea. Harvard University Press.