Changuu

Changuu Island (also known as Kibandiko, Prison or Quarantine Island) is a small island 5.6 km (3.5 mi) northwest of Stone Town, Unguja, Zanzibar, Tanzania. The island is around 800 m (2,600 ft) long and 230 m (750 ft) wide at its broadest point.[1] The island saw use as a prison for rebellious slaves in 1860s and also functioned as a coral mine.

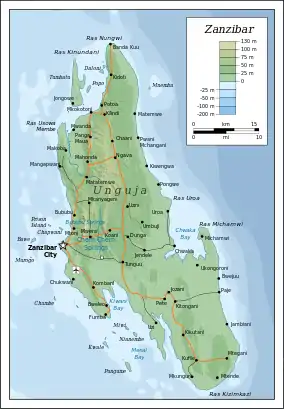

Unguja and surrounding islands | |

Changuu | |

| Geography | |

|---|---|

| Location | Indian Ocean |

| Coordinates | 6°7′9.81″S 39°9′56.06″E |

| Archipelago | Zanzibar Archipelago |

| Length | 0.8 km (0.5 mi) |

| Width | 0.23 km (0.143 mi) |

| Administration | |

| Region | Zanzibar |

The British First Minister of Zanzibar, Lloyd Mathews, purchased the island in 1893 and constructed a prison complex there. No prisoners were ever housed on the island and instead it became a quarantine station for yellow fever cases. The station was only occupied for around half of the year and the rest of the time it was a popular holiday destination. More recently, the island has become a government-owned tourist resort and houses a collection of endangered Aldabra giant tortoises which were originally a gift from the British governor of the Seychelles.

History

Changuu is named after the Swahili name of a fish which is common in the seas around it, though it is shown as "Kibandiko Island" on some older maps, but this name is no longer used.[1][2] The island was uninhabited until the 1860s when the first Sultan of Zanzibar, Majid bin Said, gave it to two Arabs who used it as a prison for rebellious slaves prior to shipping them abroad or selling them at the slave market in Zanzibar's Stone Town.[3]

Zanzibar became a British protectorate following the 1890 Heligoland-Zanzibar Treaty with Germany, this resulted in the appointment of a British First Minister, Lloyd Mathews, in October 1891.[4][5] Mathews purchased Changuu from its Arab owners on behalf of the Zanzibar government in 1893 with the intention of building a prison upon it.[1] The prison was to have housed violent and recidivist criminals from the part of the African mainland which was then under the jurisdiction of Zanzibar.[3] Despite the prison buildings being completed in 1894, causing the island to become known commonly as "Prison Island", the facility never housed prisoners.[1]

The British authorities were concerned by the risk of disease epidemics affecting Stone Town, then East Africa's main port. To combat this threat Changuu was turned into a quarantine island serving all of the British territories in East Africa. The old prison was converted into the facility's hospital and in 1923 the island was officially renamed Quarantine Island.[1] Quarantine cases would be taken from the ships and monitored on the island for between one and two weeks before being allowed to progress with their journey.[2] The main disease that was monitored was Yellow Fever.[3]

Ships typically only arrived in East Africa during the period running from December to March and so the island was usually empty of quarantine cases for a large part of the year.[1] During the empty period the island became a popular leisure resort for European people and local residents of Zanzibar. A building, known as the European Bungalow, was built in the late 1890s to cater for the holiday makers although the number of visitors had to be limited as the only freshwater on the island was rainwater stored in underground tanks.[1] Large pits on the island remained from earlier coral mining for use as a construction material and these pits were cleaned out and used as swimming pools.[2] A new complex of quarantine buildings was erected in the south-west of the island in 1931 which gave an improved quarantine capacity of 904 persons.[1]

Giant tortoises

In 1919 the British governor of Seychelles sent a gift of four Aldabra giant tortoises to Changuu from the island of Aldabra.[1] These tortoises bred quickly and by 1955 they numbered around 200 animals. However people began to steal the tortoises for sale abroad as pets or for food and their numbers dropped rapidly. By 1988 there were around 100 tortoises, fifty in 1990 and just seven by 1996.[2] A further 80 hatchlings were taken to the island in 1996 to increase the numbers but 40 of them vanished. The Zanzibar government, with assistance from the World Society for the Protection of Animals (Now known as World Animal Protection) built a large compound for the protection of the animals and by 2000 numbers had recovered to 17 adults, 50 juveniles and 90 hatchlings.

The species is now considered vulnerable and has been placed on the IUCN Red List by the International Union for Conservation of Nature. More tortoises, mainly juveniles, continue to be brought to the island from other locations for conservation.[2] There is a dedicated foundation on the island which looks after the tortoises' welfare.[1] Visitors are able to observe and feed the tortoises.[2]

Changuu today

The island lost its use as a quarantine station, but remained in the ownership of the government who converted the newer quarantine buildings into a guesthouse.[1] This ceased to function but has since been reopened as a hotel by a private company.[2] There are 15 holiday cottages in the northwest of the island as well as a tennis court, swimming pool and library and the old European Bungalow has been turned into a restaurant named after Mathews.[1] Freshwater is transported to the island via an underwater pipe from the Zanzibar mainland.[1]

The island is still owned by the government, which charges a US$4 entry fee.[2] The old prison remains standing, providing shelter for some of the tortoises and the cells can be visited.[3][6]

References

- Changuu Private Island Paradise. "History". Archived from the original on 2008-03-22. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- McIntyre, Chris (2006). "Islands near Zanzibar Town". Zanzibar Travel Guide. Bradt Travel Guides. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- Zanzibar Commission for Tourism. "Dhow Cruising". Archived from the original on 2008-09-19. Retrieved 2008-03-15.

- Pouwels 1987, p. 164.

- Milne, Lynne. "Lloyd Mathews". Dictionary of National Biography.

- Planet Aware. "Changuu Island". Archived from the original on 2012-03-20. Retrieved 2015-05-20.

Bibliography

- Pouwels, Randall L (1987). Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast, 800-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-52309-5..