Mountain plover

The mountain plover (Charadrius montanus) is a medium-sized ground bird in the plover family (Charadriidae). It is misnamed, as it lives on level land. Unlike most plovers, it is usually not found near bodies of water or even on wet soil; it prefers dry habitat with short grass (usually due to grazing) and bare ground.

| Mountain plover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Charadrius |

| Species: | C. montanus |

| Binomial name | |

| Charadrius montanus Townsend, 1837 | |

| |

Description

The word plover came from a Latin word pluvia which means "rain". In Medieval England some migratory birds became known as plovers because they returned to their breeding grounds each spring with rain. In 1832 American naturalist John Kirk Townsend spotted a species of unknown bird near the Rocky Mountains, and assumed that all these birds live in mountains. The plover comes back each spring to its breeding grounds, and so the wrong name mountain plover was given to the species. The mountain plover is 8 to 9.5 inches (20 to 24 centimetres) long and weighs about 3.7 ounces (100 grams). Its wingspread is 17.5 to 19.5 inches (44 to 50 centimetres). The mountain plover's call consists of a low, variable whistle. Both sexes are of the same size. In appearance it is typical of Charadrius plovers, except that unlike most, it has no band across the breast. The upperparts are sandy brown and the underparts and face are whitish. There are black feathers on the forecrown and a black stripe from each eye to the bill (the stripe is brown and may be indistinct in winter); otherwise the plumage is plain. The mountain plover is much quieter than its relative the killdeer. Its calls are variable, often low-pitched trilled or gurgling whistles. In courtship it makes a sound much like a far-off cow mooing.

Distribution

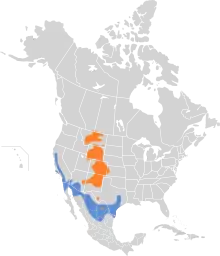

It breeds in the high plains of North America from extreme southeastern Alberta and southwestern Saskatchewan to northern New Mexico and the Texas panhandle, as well as an isolated site in the Davis Mountains of West Texas. About 85 percent of the population winters in the San Joaquin and Imperial Valleys in California. Its winter range also extends along the U.S.-Mexican border, more extensively on the Mexican side. The mountain plover needs about 70 acres of territory for breeding, and about 25 acres for survival in non-breeding times.

Around late July, mountain plovers leave their breeding range for a period of post-breeding wandering around the southern Great Plains. Little is known about their movements at this time, although they are regularly seen around Walsh, Colorado and on sod farms in central New Mexico. By early November, most move southward and westward to their wintering grounds. Spring migration is apparently direct and non-stop.

Ecology and status

It feeds mostly on insects and other small arthropods. It often associates with livestock, which attract and stir up insects.

Mountain plovers nest on bare ground in early spring (April in northern Colorado). The breeding territory must have bare ground with short, sparse vegetation. Plovers usually select a breeding range that they share with bison and black tailed prairie dogs. These animals are grazers that keep vegetation short. Plovers like to nest among prairie dog colonies because the foraging and burrowing that these animals do expose even more bare soil which creates an ideal habitat for plover nest sites. It is believed that plovers like to nest on bare soil because they blend into the land hiding them from birds that may prey on them and the short vegetation allows them to easily detect predators on the ground. It is also believed it is easier for them to spot insects to eat.

A mountain plover nest has a survival rate that ranges from 26 to 65%. This wide range may be due to the impact that varying climate has on nest survival. A nest made in a colder climate with less precipitation has a better chance of survival. These conditions are preferred because of the climate's effect on the eggs directly, changes in predatory behavior, or changes in vegetation that can affect the mortality rates of parents. Higher heat may expose eggs to heat stress;also, a wetter climate may factor in to predators having a more sensitive sense of smell, aiding the discovery of nests. Nest predators are the biggest cause of nest destruction. Because of this, it is a primary driving force of survival rate. Increase in soil moisture may the environment of bare grounds and short grass that prairie birds thrive in.

Their breeding season extends over the summer months and ends some time around late July or early August. During mating the male will set a territory and perform displays to attract a female. Females lay multiple clutches of eggs with three eggs to a clutch; the eggs are off-white with blackish spots. Egg size decreases as the breeding season goes on because of the high energy cost on the females. It has been found that eggs laid during a time of drought tend to be larger providing the incubating chick with more nourishment and so a greater chance at survival. Mountain plovers perform uniparental incubation by both sexes. Females leave their first clutch to be incubated and tended to by the male and then lay a second clutch, which she tends to herself. This type of incubation suits the mountain plover well and allows for a greater yield of chicks compared to similar species of birds in which both the male and female tend a single clutch together. Females can mate with several males and have several male tended nests in one breeding season. This would result in a greater reproductive success for the female but there is a high energy cost on the female laying so many eggs and so it is more common for a female to lay only two clutches. If the eggs survive various dangers, especially such predators as coyotes, snakes, and swift foxes, they hatch in 28 to 31 days, and the hatchlings leave the nest within a few hours. In the next two or three days, the family usually moves one to two kilometers from the nest site to a good feeding area, often near a water tank for livestock.

The population has been estimated at between 5,000 and 10,000 adult birds, although those numbers have recently been revised to the range of 11,000 to 14,000, with a total population estimate of about 15,000 to 20,000. In March 2009, a multi-agency report, the first of its kind, issued by the Cornell University Lab of Ornithology in conjunction with federal agencies and other organizations, indicated that the mountain plover is one of the birds showing serious declines in population.[2] The population of mountain plovers is in decline because of cultivation, urbanization, and over-grazing of their living space.

Fritz Knopf has closely studied the mountain plover, and has tracked population declines. These downhill trends led to a 1999 proposal to list them as a threatened species. On June 29, 2009, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service published a proposed rule to list the mountain plover as threatened under the Endangered Species Act.[3]

Preservation

A 2005 report details that in a study conducted by Stephen J Dinsmore, Gary C White, and Fritz L Knopf, the populations of mountain plovers and prairie dogs in southern Phillips County in north-central Montana were observed in the effort to provide clues about the ecosystem and mountain plover preservation. Mountain plovers like to build their habitats in prairie dog colonies, meaning that an increase in prairie dogs will coincide with an increase in mountain plovers. This knowledge can be useful in mountain plover conservation efforts. The loss of prairie dog colonies is a huge threat to mountain plovers in Montana; if prairie dog colonies can be preserved, there is a greater chance that mountain plovers can be saved. Other proposed plans of preservation include protecting remaining breeding and wintering habitats, and stopping the conversion of grasslands for agricultural purposes.

The connection between mountain plovers and prairie dogs is particularly strong in Montana, but less so in the grasslands of Colorado and the grasslands and shrub-steppe habitats of Wyoming. In places where prairie dogs aren't as prominent in the ecosystem, fire or grazing can act as substitutes for prairie dogs in creating suitable plover nesting because they maintain low vegetation. In the construction of suitable plover habitats, more success would be found in short-grass prairie habitats. However, concerning conservation, a large portion of the overall plover population breeds near the northern limit of their range in Montana, and it would be wise to make this area a conservation priority.

The population of plovers in Wyoming is lower than that of other states, but Wyoming's population of mountain plovers and mostly intact expanses of grazed rangeland will probably become much more important in the coming years as urban and agricultural development continues in contiguous states.

In Oklahoma, 90% of mapped mountain plover locations are in cultivated fields, often bare and flat. Their preferred land areas contain clay loam soils, as the sandier soils are less reliable when sand can easily be blown around, covering nests, obscuring vision, and irritating eyes. Additional study is needed to help ensure the continued presence of mountain plovers in Oklahoma.

Mountain plover populations should continue to be monitored and investigated so as to understand how to support their survival. Plovers are important to the ecosystem at large because they are considered indicators of the health of their respective habitats. Local population managers can best help the plovers by protecting the land and prairie dog colonies from human disturbances such as mining, and monitoring the size and health of suitable plover habitat in each region.

Lower chick survival contributes to the decline in population. Efforts to increase nest survival provides minimal growth when compared to ensuring juvenile chick survival. Population growth can be helped more by learning more about post-egg survival.

Footnotes

- BirdLife International (2020). "Charadrius montanus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22693876A178907575. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22693876A178907575.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- Many bird populations in trouble, report says. CNN (2009-03-19). Retrieved on 2011-05-10.

- FR Doc 2010-15583. Edocket.access.gpo.gov. Retrieved on 2011-05-10.

References

- Knopf, Fritz L. (1997): A Closer Look: Mountain Plover. Birding 29(1): 38–44.

- Knopf, Fritz L. & Wunder, M.B. (2006): Mountain Plover. In: Poole, A. & Gill, F. (eds.): The Birds of North America 211. Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia, PA & American Ornithologists' Union, Washington, D.C. Online version, retrieved 2008-MAY-23. doi:10.2173/bna.211 (requires subscription)

- Sibley, David Allen (2000): The Sibley Guide to Birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-679-45122-6

- Dinsmore S, White G, Knopf F. 2005. Mountain Plover Population Responses to Black-Tailed Prairie Dogs in Montana. Journal of Wildlife Management, 69(4):1546-1553.

- Skrade, P, Dinsmore, S. (2013). Egg-Size Investment in a Bird with Uniparental Incubation by Both Sexes. The Condor, 115 (3): 508–514.

- Goguen, C. (2012). Habitat use by Mountain Plovers in Prairie Dog Colonies in Northeastern New Mexico. Journal of Field Ornithology, 83 (2): 154–165.

- May, Holly. Mountain Plover. 22. Madison: Wildlife Habitat Management Institute, 2001. 1–11. Web. <https://prod.nrcs.usda.gov/Internet/FSE_DOCUMENTS/nrcs143_022162.pdf>.

- Victoria J. Dreitz, Reesa Yale Conrey, Susan K. Skagen, (2012): Drought and Cooler Temperatures Are Associated with Higher Nest

Survival in Mountain Plovers. "Avian Conservation and Ecology" Vol. 7 No. 1 Article. 6

- Stephen J. Dinsmore, Michael B. Wunder, Victoria J. Dreitz, and Fritz L. Knopf, (2010): An Assessment of Factors Affecting Population Growth of the Mountain Plover. "Avian Conservation and Ecology" Vol. 5 No. 1 Article. 5

- Cook, Kevin. "Shorebirds in a land without shore." Reporter - Herald. 24 04 2013: Print. <http://www.reporterherald.com/ci_23089051/shorebirds-land-without-shore>.

- Childers T, Dinsmore S. 2008. Density and Abundance of Mountain Plovers in Northeastern Montana. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology, 120(4):700-707.

- Plumb R, Knopf F, Anderson S. 2005. Minimum Population Size of Mountain Plovers Breeding in Wyoming. The Wilson Bulletin, 117(1):15-22.

- McConnell et al. 2009. Mountain Plovers in Oklahoma: distribution, abundance, and habitat use. Journal of Field Ornithology, 80(1):27-34.