Snowy plover

The snowy plover (Charadrius nivosus) is a small wader in the plover bird family, typically about 5-7" in length.[2] It breeds in the southern and western United States, the Caribbean, Ecuador, Peru, and Chile. Long considered to be a subspecies of the Kentish plover, it is now known to be a distinct species.

| Snowy plover | |

|---|---|

| |

| Near Cayucos, California | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Charadriiformes |

| Family: | Charadriidae |

| Genus: | Charadrius |

| Species: | C. nivosus |

| Binomial name | |

| Charadrius nivosus (Cassin, 1858) | |

| |

Parts of or entire beaches along the Central California coast and Oregon coast are protected as nesting sites for the snowy plover and completely restricted to humans.

Taxonomy and systematics

Plovers (Charadriinae) are a subfamily of small shorebirds that breed in open habitats on all continents except Antarctica.[3] Together with the lapwings (Vanellinae), they form the family Charadriidae. The snowy plover is a species within the genus Charadrius, which comprises 32 extant species and is therefore the most specious genus of the family.[4] The genus name Charadrius derives from the Greek χαραδριός meaning "ravine", and hints at the occurrence of these birds along rivers.[3] The species name nivosus is Latin for "snowy".[5] Snowy plover is the official common name designated by the International Ornithologists' Union (IOU).[6]

The snowy plover was first described by the American ornithologist John Cassin in 1858 as Aegialitis nivosa,[note 1] based on a skin collected by William P. Trowbridge in the Presidio of San Francisco. This skin, the holotype of the species, was subsequently lost. Although originally part of the collection of the National Museum of Natural History, it was given to the collector Henry E. Dresser of England in 1872. In 1898, the Dresser collection was transferred to the Victoria University of Manchester, but the skin was apparently not part of this transfer. Joseph Grinnell, who attempted to locate the holotype in 1931, suggested that Dresser might not have been aware of the significance of the specimen and gave it elsewhere.[7]

The snowy plover is closely related, and visually similar, to the Kentish plover (Charadrius alexandrinus) of the Old World, and much debate revolved around the question whether the two represent a single or separate species.[8] Harry C. Oberholser, in 1922, argued that the differences in plumage between these species are not consistent, and no clear line of demarcation could be drawn. Consequently, he classified the two subspecies of the snowy plover that were recognised at that time as subspecies of the Kentish plover (as Charadrius alexandrinus nivosus and Charadrius alexandrinus tenuirostris).[9] This assessment was subsequently followed by most authors, until a 2009 genetic analysis by Clemens Küpper and colleagues re-established the snowy plover as a distinct species. These authors noted that, besides differences in the mitochondrial and nuclear DNA, snowy plovers also differ from Kentish plovers in being smaller, having shorter tarsi and wings, in their chick plumages, as well as in the advertisement calls of the males.[8] In 2011, the International Ornithological Congress (IOC) and the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU) have recognized them as separate species.[10]

The interrelationships of plover species are still debated. Does Remedios and colleagues, in 2015, recognised six distinct clades within the genus Charadrius, with the snowy plover forming a clade with the Kentish, the white fronted, the Malaysian, the chestnut-banded, and the red-capped plover. Members of this clade inhabit every continent except for Antarctica. Bradley Livezey, in 2010, instead grouped the snowy, Kentish, and Malaysian plovers in a clade together with the Siberian sand plover and the greater sand plover.[10]

Description

The snowy plover is a plump snorebird with a large head, a short and slender bill, and short neck and tail. It is a small plover, with adults ranging from 15 to 17 cm (5.9 to 6.7 in) in length, from 34 to 43.2 cm (13.4 to 17.0 in) in wingspan, and from 40 to 43 g (1.4 to 1.5 oz) in weight. Its body is typically held horizontally.[13] Compared to other plovers, its legs are relatively long and its wings short.[14] The bill is black, the iris dark brown, and the legs gray to black.[11]

Snowy plovers are pale brown above and white below, with a white band on the hind neck and a smudgy eyestripe. The breeding male has black patches behind the eye ("ear patch") and on the side of the neck. The neck patches on both sides are only rarely joined at the front to form a continuous breast band as in many other plovers, and in most cases are well separated, giving the appearance of a "broken" breast band. Breeding males have a black patch on the forehead, and many also develop a reddish crown. The breeding female lacks the reddish crown and is slightly duller, and typically one or more of the patches are partly or completely brown. Outside the breeding season, the neck and ear patches are pale and the foreneck patch is absent, and plumages of males and females cannot be distinugished. Newly hatched chicks have pale uppersides with brown to black spots and are white below.[11][14]

Similar species within its range include the piping plover Charadrius melodus), the collared plover (Charadrius collaris), the semipalmated plover (Charadrius semipalmatus), and Wilson's plover (Charadrius wilsonia). Amongst other features, the snowy plover differs from these species in its black and slender bill (shorter and thicker in piping plover and longer and thicker in Wilson's Plover), in its gray to black legs (orange or yellow in piping, collared, and semipalmated plovers), and the "broken" breast band (usually complete in semipalmated, Wilson's, and breeding collared plovers).[11]

Vocalizations

The typical call is a sweet, repeated "tu-wheet", which is given in a wide range of contexts.[11][13] In males, these include, amongst others, advertisement while standing in territories and courtship. In both sexes, the call may be given in situations of threat, aggression, distress, and alarm. This call differs between sexes, being shorter, quieter, and hoarser in the female. Other calls include a repeated "purrt" that is given during breeding season, for example while flying from nest sites or when other plovers intrude their territory. A single "churr" is mostly given by males while defending territory or offspring from other plovers. Outside the breeding season, a repeated "ti" is given when disturbed while resting, and is often followed by flight. Chicks give a "peep" call from up to two days before hatching and continuing until their first flight.[11]

Behavior and ecology

Feeding

The species feeds on invertebrates such as crustaceans, worms, beetles, and flies. An analysis of feces from a coastal population of California during breeding season revealed 72% beetles, 44% flies, and 25% insect larvae. Prey is taken from above and below the sand surface, from plants or carcasses. In inland habitats, snowy plovers usually forage on wet substrates that may be under a shallow water cover.[11] As is typical for plovers, prey is found visually by briefly standing to scan the area, which is followed by running and capturing.[11][13] Snowy plovers also forage by probing the substrate with their bills, by charging or hopping into accumulations of flies, and by "foot trembling" on wet substrates or in shallow water, where one foot shakes to stirr up prey. Brine fly larvae are often shaked before consumption, and captured flies are often bitten two or three times times. Snowy plovers may forage during day and night, with one invividual observed feeding in almost complete darkness. Snowy plovers drink when fresh water is available, but when it is not, they can sustain on the water content of their prey.[11]

Territoriality and roosting

At the beginning of the breeding season, the male, while still unpaired, will establish and defend an territory, which is then advertised to a female by calling and excavating scrapes. A pair will continue to defend the territory. After the chicks hatch, the brood will soon then begin to move around, when the adults will defend the surrounding radius rather than a fixed territory. When defending a territory, males may attempt to intimidate conspecifics by using the "Upright Display" posture, in which the body is upright with erected breast feathers. They may also run or fly at, or fight with intruders. Fighting may involve jumping at each other breast-to-breast with flapping wings and mutual pecking and shoving. In some cases, combatans pull on each others feathers, and may even pull out a flight feather. Fights with intermittent short breaks can last up to 1.5 hours. Territories are defended not only against conspecifics but also against some other bird species, including semipalmated plovers and whimbrels. Territories are probably not important for protecting food resources, as the plovers often feed in flocks up to 6 km away from their territories. However, in Kansas and Oklahoma, where the birds are more stationary, protection of feeding grounds could be more important. The size of territories is variable, and sizes between 0.1 and 1 ha have been reported.[11]

Outside the breeding season, snowy plovers will often roost in groups of several to more than 300 birds. Roosting places are typically on the ground in footprints, vehicle tracks, or behind objects such as driftwood. When attacked by a bird of prey, the birds will take flight to form a highly coordinated flight formation.[11]

Breeding

Snowy plovers are facultative polygamous, with females, and less frequently males, often abandoning their mate soon after the chicks have hatched. The deserting female will then pair with a new male and renest, sometimes a few hundred kilometers away from its first brood, while the male will continue to rear the chicks. This polygamy is most pronounced where the breading season is long, when birds may start two, and sometimes three, broods per season. On the other hand, birds do generally not brood twice in the Great Plains, where the breeding season is short. A biased sex ratio also appears to favour polygamy: males are generally more common than females, with one study reporting that males were 1.4 times more common than females in California. The causes for such pronounced sex ratios are unknown. Rarely, males breed with two females at the same time. Pairs can also be reestablished in the next breeding season, which occurred in 32 to 45% of cases in central California, or within the same season in the third breeding attempt of the female.[11] The polygamous mating system of the snowy plover is uncommon, but the closely related Kentish plover shows a similar behavior.[3]

Snowy plovers nest in ground scrapes that are excavated by the male as an important part of the courtship ritual. In the coastal areas of California, males excavated an average of 5.6 scrapes per territory. A scrape may be constructed within a few minutes, often near conspicuous landmarks such as rocks and grass patches. One of these scrapes is later selected by the pair for nesting, commonly the scrape where most copulations took place. Both before and during incubation, the adults continue to line the nest with small objects such as stones and shell pieces. Where the ground is too hard to construct scrapes, other depressions such as animal and vehicle tracks are choosen.[11]

The species lies 3 eggs on average, but clutch size ranges from 2 to 6 eggs. When only a single egg is produced, the clutch is usually abandoned. Eggs are oval or asymmetric in shape and have a matte and smooth surface. In coastal California, they average at 31 mm in length, 23 mm in width, and 8.5 g in weight, which accounts for 20% of the body weight of the female. Egg color is brownish-yellow, with dark brown or black speckles that become more numerous towards the blunt end of the egg. The female lays one egg every 47 to 118 hours until the clutch is complete. The time interval between egg laying and hatching varies geographically and seasonally, ranging between 23 and 49 days. Continuous incubation starts upon clutch completion; while still incomplete, males and females spent only around a fourth of daytime incubating. In coastal areas of California, females tend to inclubate during the day, while males incubate at night. The reason for this pattern is unclear, and hypotheses include a need of the female to feed at night to regain energy lost from egg laying and the need of the male to defend the territory during daytime, amongst others. Under hot conditions greater 40°C, the male and female take turns every hour or less to prevent overheating.[11]

A day before hatching, chicks and parents communicate by calling. After hatching, the parents will carry eggshells away from the nest. The chicks are presocial and able to walk and swim one to three hours after hatching. Parents do not feed their chicks, but will lead them to feeding areas. Parents will continue to brood their chicks after hatching – in the coastal areas of northern California, chicks less than 10 days old were brooded 58% of the time on average. When parents sense potential danger such as approaching predators, the chicks will lie flat against the ground. In western North America, chicks are attended for 29 to 47 days after hatching, often by the male after the female deserted. In the more eastern populations, however, chicks are often attended until they fledge.[11]

Distribution and habitat

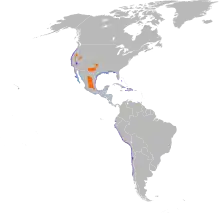

The snowy plover is distributed along the Pacific coast of North and South America, in the Gulf of Mexico, and in areas inland of the US and Mexico. Along the Pacific coast of North and Central America, it breeds from south Washington down to Oaxaca in Mexico; non-breeding individuals can be found as far south as Panama. In South America, it breeds from south Equador to Chiloé Island in Chile. In the Gulf region, breeding occurs eastwards as far as the Virgin Islands and Margarita Island. These coastal populations consist of both migratory and residental birds; migration occurs over relatively short distances north- or southward along the coast. Inland breeding populations exist in the US eastward to the Great Plains of Kansas and Oklahoma, as well as in Mexico north of Mexico City. These populations are mostly migratory, with western populations migrating to the Pacific coast, and the Great Plains populations to the Gulf of Mexico coast. Breeding has been recorded at elevations up to 3,048 metres (10,000 ft).[11]

The species inhabits open areas in which vegetation is absent or sparse, in particular coastal sand beaches and shores of saline or alkaline lakes. It also breeds on river bars that are located close to the coast, and adopts human-made habitats such as wastewater and salt evaporation ponds, dammed lakes, and dredge spoils. It requires the proximity of water, although it may breed on salt flats where only very little water remains.[11]

Threats and conservation efforts

.jpg.webp)

On March 5, 1993 the western snowy plover was listed as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. At this time, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service declared three factors as restricting population recovery: habitat degradation, resulting from invasive species and coastal developments; disturbances due to human activity; and predation of chicks and eggs.[15] As of June 19, 2012, the habitat along the California, Oregon, and Washington Coasts have been listed as critical.[16] In 2016, risk assessments by the IUCN listed the snowy plover as near threatened and found that the species had an overall decreasing population trend. [17] In many parts of the world, it has become difficult for this species to breed on beaches because of disturbance from the activities of humans or their animals.[18]

University of California, Santa Barbara

The University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB) is currently endeavoring to rehabilitate snowy plover populations by protecting beaches along the central California coastline that runs along part of the university campus.[19] UCSB has had some success in encouraging reproduction; the university also often trains students and other volunteers to watch over protected beaches during the daytime to ensure no one disturbs nesting grounds. But even with the conservation efforts, their population is slowly dwindling, it's estimated that only about 2,500 western snowy plovers breed along the Pacific Coast.[20]

Point Reyes National Seashore

Scientists from Point Blue Conservation Science and the National Park Service (NPS) have instituted management measures to encourage successful snowy plover reproduction efforts on Point Reyes National Seashore. Vulnerable nests are protected by exclosures, fencing enforces seasonal closures around nesting habitat, and sections of the Great Beach are closed to reduce human disturbance.[21] To counteract the impact of increased recreation on weekends and holidays, the park uses informational signs and brochures detailing the vulnerability of the species, while volunteer docents have been present to help educate visitors on the species since 2001.[22]

Vandenberg Space Force Base, California

The beaches lining Vandenberg Space Force Base on the Central coast of California are also home to several protected areas where breeding has been successful in recent years. Access to these beaches is limited to certain times of the year, and very specific areas are open to keep the bird protected. Most of these beaches are only open to military personnel and their families.[23]

Oregon

Conservation of the western snowy plover is being done by a consortium of organizations including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the U.S. Forest Service, the Bureau of Land Management, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, and the Oregon Parks and Recreation Department. Since conservation measures were put in place in the 2000s, including beach restrictions and control of invasive beach grasses, snowy plover populations have increased by a factor of more than seven.[24]

Notes

- Cassin, 1858, in Baird, Cassin, and Lawrence, Rep. Expl. and Surv. R. R. Pac, vol. 9, pp. xlvi, 696

References

- BirdLife International (2020). "Charadrius nivosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2020: e.T22725033A181360276. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2020-3.RLTS.T22725033A181360276.en. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- Bull, John; Farrand, John (1994). National Audubon Society Field Guide to North American Birds, Eastern Region (second ed.). Chanticleer Press, Inc.

- Colwell, Mark A.; Haig, Susan M. (2019). "An Overview of the World's Plovers". In Colwell, Mark A.; Haig, Susan M. (eds.). The population ecology and conservation of Charadrius plovers. London: CRC Press, Taylor/Francis Group. pp. 3–15.

- Winkler, David W.; Billerman, Shawn M.; Lovette, Irby J. (2020). "Plovers and Lapwings (Charadriidae)". Birds of the World. doi:10.2173/bow.charad1.01species_shared.bow.project_name. ISSN 2771-3105. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- Jobling, James A. (2010). Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4. OCLC 1040808348 – via Biodiversity Heritage Library.

- Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (July 2023). "Buttonquail, thick-knees, sheathbills, plovers, oystercatchers, stilts, painted-snipes, jacanas, Plains-wanderer, seedsnipes". IOC World Bird List Version 13.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 10 October 2023.

- Grinnell, Joseph (1932). Type localities of birds described from California. Vol. 38. University of California Press.

- Küpper, Clemens; Augustin, Jakob; Kosztolányi, András; Burke, Terry; Figuerola, Jordy; Székely, Tamás (2009). "Kentish versus Snowy Plover: phenotypic and genetic analyses of Charadrius alexandrinus reveal divergence of Eurasian and American subspecies". The Auk. The American Ornithologists’ Union. 126 (4): 839–852. doi:10.1525/auk.2009.08174. hdl:10261/41193. S2CID 42282029.

- Oberholser, Harry C. (1922). "Notes on North American birds. XI". The Auk. 39 (1): 72–78.

- Küpper, Clemens; dos Remedios, Natalie (2019). "Defining Species and Populations". In Colwell, Mark A.; Haig, Susan M. (eds.). The population ecology and conservation of Charadrius plovers. London: CRC Press, Taylor/Francis Group. pp. 17–43.

- Page, G.W.; Stenzel, J.S.; Warriner, J.S.; Warriner, J.C.; Paton, P.W. (2020). Poole, A.F. (ed.). "Snowy Plover (Charadrius nivosus)". Birds of the World. Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bow.snoplo5.01. Retrieved 9 October 2023.

- "Cuban snowy plover". Retrieved 11 October 2023.

- "Snowy Plover Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 30 September 2020.

- Sibley, David Allen (2016). Sibley Birds West (2nd ed.). Knopf. ISBN 9780593536100.

- 1. Page 2. Stenzel, 1. Gary W. 2. Lynne E. (1981). ""The Breeding Status of the Snowy Plover in California"". Western Birds. 12 (1): 1–40 – via Federal Register.

- "Western Snowy Plover Species Profile". www.fws.gov. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 8 February 2016.

- International), BirdLife International (BirdLife (1 October 2016). "IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: Charadrius nivosus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- Edwards, Christian. Snowy Plover Nest Density and Reproductive Success at Great Salt Lake, Utah (Thesis). Fort Hays State University.

- "2003 UCSB Press Release on snowy plovers". World Heritage. Retrieved 21 May 2007.

- "Western Snowy Plover". Monterey Bay Aquarium. Retrieved 6 March 2020.

- "Snowy Plovers at Point Reyes - Point Reyes National Seashore (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- "Volunteer: Snowy Plover Docent - Point Reyes National Seashore (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 25 October 2023.

- Nguyen, Julia (24 September 2020). "Vandenberg Air Force Base reopens beaches with end of snowy plover season". KEYT. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- Urness, Zach (20 March 2023). "Western snowy plovers go from near extinction to expanded growth on Oregon Coast". Salem Statesman Journal. Retrieved 3 August 2023.

Bibliography

- Gill, F.; Donsker, D., eds. (2011). "IOC World Bird List (v 2.9)". Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- Chesser, R. Terry; Banks, Richard C.; Barker, F. Keith; Cicero, Carla; Dunn, Jon L.; Kratter, Andrew W.; Lovette, Irby J.; Rasmussen, Pamela C.; Remsen, J. V.; Rising, James D.; Stotz, Douglas F.; Winker, Kevin (2011). "Fifty-second supplement to the American Ornithologists' Union Check-List of North American Birds". Auk. 128 (3): 600–613. doi:10.1525/auk.2011.128.3.600. S2CID 13691956.

- Kaufman, Kenn. “Snowy Plover.” Audubon, 15 Jan. 2020, www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/snowy-plover.

External links

- Western Snowy Plover - Tools and Resources for Recovery

- "Charadrius nivosus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- BirdLife species factsheet for Charadrius nivosus

- "Charadrius nivosus". Avibase.

- Snowy plover photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Charadrius nivosus at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Snowy plover on Xeno-canto.

- Charadrius nivosus in Field Guide: Birds of the World on Flickr

- snowy-plover/charadrius-nivosus Snowy plover media from ARKive