Charles, Duke of Brittany

Charles of Blois-Châtillon (1319 – 29 September 1364), nicknamed "the Saint", was the legalist Duke of Brittany from 1341 until his death, via his marriage to Joan, Duchess of Brittany and Countess of Penthièvre, holding the title against the claims of John of Montfort. The cause of his possible canonization was the subject of a good deal of political maneuvering on the part of his cousin, Charles V of France, who endorsed it, and his rival, Montfort, who opposed it. The cause fell dormant after Pope Gregory XI left Avignon in 1376, but was revived in 1894. Charles of Blois was beatified in 1904.

| Blessed Charles of Blois-Châtillon | |

|---|---|

| |

| Duke of Brittany | |

| Reign | 30 April 1341 – 29 September 1364 |

| Predecessor | John III |

| Successor | John IV |

| Born | c. 1319 Blois (France) |

| Died | 29 September 1364 (aged 44–45) Auray |

| Spouse | Joan, Duchess of Brittany |

| Issue | John I, Count of Penthièvre Marie, Duchess of Anjou Margaret, Countess of Angoulême |

| House | House of Blois-Châtillon |

| Father | Guy I, Count of Blois |

| Mother | Margaret of Valois |

Charles de Châtillon | |

|---|---|

_%C3%89glise_Notre-Dame_Statue_01.JPG.webp) Statue of Blessed Knight Charles Châtillon de Blois in the Church of Notre-Dame de Bulat-Pestivien (Bretagne) | |

| Duke of Brittany, Patron of Europe | |

| Born | c. 1319 Blois, France |

| Died | 29 September 1364 (aged 44 – 45) Battle of Auray, Auray, France |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church |

| Beatified | 14 December 1904 (confirmation of cultus) by Pope Pius X |

| Feast | 29 September (General Roman Calendar) |

| Attributes | sword, tabard with Brittany's coat of arms, armor, shield |

| Patronage | Army soldiers, agricultural workers |

Biography

Charles was born in Blois, the son of Guy de Châtillon, count of Blois, by Margaret of Valois, a sister of King Philip VI of France. A devout ascetic from an early age, he showed interest in religious books but was forbidden from reading them by his father, as they did not seem appropriate to his position as a knight.[1] As he grew older, Charles took piety to the extreme of mortifying his own flesh.[2] It is said that he placed pebbles in his shoes, slept on straw instead of a bed, confessed every night in fear of sleeping in a state of sin, and wore a cilice under his armor in battle. He was nevertheless an accomplished military leader, who inspired loyalty by his religious fervour.[1]

Marriage

On 4 June 1337 in Paris, he married Joan the Lame, heiress and niece of John III, Duke of Brittany.[3][1]

Breton War of Succession

Together, Charles and his wife, Joan of Penthièvre, fought the House of Montfort in the Breton War of Succession (1341–1364), with the support of the crown of France.[1] Despite his piety, Charles did not hesitate in ordering the massacre of 1,400 civilians after the siege of Quimper as well as the massacre of thousands after the siege of Guerande.[4] After initial successes, Charles was taken prisoner by the English in 1347.[1] His official captor was Thomas Dagworth.[5]

He stayed nine years as prisoner in the Kingdom of England. During that time, he used to visit English graveyards, where he prayed and recited Psalm 130, much to the chagrin of his own squire. When Charles asked the squire to take part in the prayer, the younger man refused, saying that the men who were buried at the English graveyards had killed his parents and friends and burned their houses.[1]

Charles was released against a ransom of about half a million écus in 1356.[6] Upon returning to France, he decided to travel barefoot in winter from La Roche-Derrien to Tréguier Cathedral out of devotion to Saint Ivo of Kermartin. When the common people heard of his plan, they placed straw and blankets on the street, but Charles promptly took another way. His feet became so sore that he could not walk for 15 weeks.[1] He then resumed the war against the Montforts.[6]

Charles was eventually killed in combat during the Battle of Auray in 1364, which with the second treaty of Guerande in 1381 determined the end of the Breton War of Succession as a victory for the Montforts.[6]

Family

By his marriage to Joan the Lame, Countess of Penthièvre, he had five children:

- John I, Count of Penthièvre (1340–1404)[7] and Viscount of Limoges.

- Guy

- Henry (d. 1400)

- Marie of Blois, Duchess of Anjou (1345–1404), Lady of Guise, married in 1360 to Louis I, Duke of Anjou[8]

- Margaret of Blois, Countess of Angoulême, married in 1351 to Charles de la Cerda (d. 1354), the Count of Angoulême and Constable of France.

According to Froissart's Chronicles, Charles also had an illegitimate child, John of Blois, who died in the Battle of Auray. However, considering Charles' extreme piety, historian Johan Huizinga regarded it unlikely that Charles actually had a child born outside marriage and that Jean Froissart was probably mistaken in identifying John as Charles' son.[2]

Veneration

Charles was buried at Guingamp, where the Franciscans actively promoted his unapproved cult as saint and martyr. Such variety of ex votos bedecked his tomb, that in 1368 Duke John IV of Brittany persuaded Pope Urban V to issue a bull directing the Breton bishops to stop this.[9] But the bishops failed to enforce it.

Nonetheless, his family successfully lobbied for his canonization as a Saint of the Roman Catholic church for his devotion to religion.[2] Bending to pressure from Charles V of France, Pope Urban authorized a commission to study the matter. Urban died December 1370 to be succeeded by Pope Gregory XI. The commission held its first meeting in Angers in September 1371, and forwarded its report to Avignon the following January. Gregory appointed three cardinals to review the matter. The Pope returned to Italy in September 1376, arriving in Rome in November 1377; he died the following March. Gregory was succeeded in Avignon by Clement VII, but the documents were probably in Rome with Pope Urban VI.[10] There appears to be no record of further activity regarding Charles' cause for canonization at this time. In 1454, Charles' grandson urged his relatives to continue to advocate for his recognition.

The process was re-opened in 1894, and on 14 December 1904, Charles de Châtillon was beatified as Blessed Charles of Blois. His feast Day is 30 September.

Image of S.Charles de Châtillon in the book Vie des Saints", Yann-Vari Perrot, publishing in 1912 (page 692)

Image of S.Charles de Châtillon in the book Vie des Saints", Yann-Vari Perrot, publishing in 1912 (page 692) The Saint Charles de Châtillon de Blois, battles gallery, Versailles castle, France

The Saint Charles de Châtillon de Blois, battles gallery, Versailles castle, France_%C3%89glise_Saint-Pierre_Vitrail_14.JPG.webp) The Saint Charles de Châtillon in the glass window of the Church Saint-Pierre in Plounéour-Trez, France

The Saint Charles de Châtillon in the glass window of the Church Saint-Pierre in Plounéour-Trez, France The Saint Charles de Châtillon in the glass window of the Church Saint-Malo in Dinan, France

The Saint Charles de Châtillon in the glass window of the Church Saint-Malo in Dinan, France_%C3%89glise_Notre-Dame_Statue_01.JPG.webp) Statue of Blessed Knight Charles Châtillon de Blois in the Church of Notre-Dame de Bulat-Pestivien (Bretagne)

Statue of Blessed Knight Charles Châtillon de Blois in the Church of Notre-Dame de Bulat-Pestivien (Bretagne) The Knight Charles de Blois-Châtillon, with his army, in the attack of Siege of Hennebont in 1342, an epic battle during the war of succession of Brittany

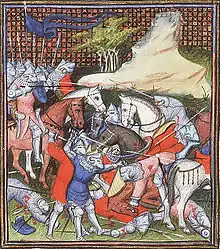

The Knight Charles de Blois-Châtillon, with his army, in the attack of Siege of Hennebont in 1342, an epic battle during the war of succession of Brittany "The Knight Charles de Châtillon is taken prisoner". Jean Froissart, Chroniques (Vol. I), Koninklijke Bibliotheek in 1816

"The Knight Charles de Châtillon is taken prisoner". Jean Froissart, Chroniques (Vol. I), Koninklijke Bibliotheek in 1816 Battle of Auray, 1364

Battle of Auray, 1364 "War of Breton Succession" (1341–1364), Jean Froissart, Paris, 9th century

"War of Breton Succession" (1341–1364), Jean Froissart, Paris, 9th century_Basilique_Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle_Vitrail_1.jpg.webp) Battle of Auray in the glass window of the Church of Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle, Rennes

Battle of Auray in the glass window of the Church of Notre-Dame-de-Bonne-Nouvelle, Rennes Battle of Auray 1364, "Chroniques"

Battle of Auray 1364, "Chroniques" Battle of Auray, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris

Battle of Auray, Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.png.webp) First Siege of Vannes in 1342 by Charles de Blois-Châtillon

First Siege of Vannes in 1342 by Charles de Blois-Châtillon Charles de Blois-Châtillon, was taken prisoner after the battle of Roche Derrien in 1347

Charles de Blois-Châtillon, was taken prisoner after the battle of Roche Derrien in 1347

See also

- John of Montfort

- Counts of Blois

- Luis de la Cerda, also known as Louis of Spain, a commander of Charles during the Breton War of Succession

- Dukes of Brittany family tree

- House of Châtillon

- Olivier IV de Clisson

References

- Huizinga (2016), p. 289.

- Huizinga (2016), p. 290.

- Prestwich 1993, p. 174.

- Sumption 1999, p. 434.

- Jones 1988, p. 265.

- Autrand 2000, p. 441.

- Hereford Brooke George, Genealogical Tables Illustrative of Modern History, (Oxford Clarendon Press, 1875), table XXVI

- Bruel 1905, p. 198.

- Jones 2000, p. 221.

- Jones 2000, p. 228.

Sources

- Autrand, Francoise (2000). "France under Charles V and Charles VI". In Jones, Michael (ed.). The New Cambridge Medieval History: Volume 6, C.1300-c.1415. Cambridge University Press.

- Bruel, François-L. (1905). "Inventaire de meubles et de titres trouvés au château de Josselin à la mort du connétable de Clisson (1407)". Bibliothèque de l'École des chartes (in French). Librairie Droz. 66 (66): 193–245. doi:10.3406/bec.1905.448236.

- Huizinga, Johan (2016) [1st pub. 1919]. Herbst des Mittelalters [The Autumn of the Middle Ages] (in German). Translated by Kurt Köster (4th ed.). Stuttgart: Reclam. ISBN 978-3-15-020366-8.

- Jones, Michael (1988). Creation of Brittany: A Late Medieval State. The Hambledon Press.

- Jones, Michael (2000). "Politics, Sanctity, and the Breton State: the Case of Blessed Charles de Blois, Duke of Brittany (d. 1364)". In Maddicott, John Robert; Palliser, David Michael (eds.). The Medieval State: Essays Presented to James Campbell. A&C Black. ISBN 9781852851958.

- Prestwich, Michael (1993). The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272-1377. Routledge.

- Sumption, Jonathan (1999). The Hundred Years War, Volume 1: Trial by Battle. Faber & Faber.