Charly García

Carlos Alberto García Moreno (born October 23, 1951) better known by his stage name Charly García,[1] is an Argentine singer-songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, composer and record producer, considered one of the most important and avant-garde figures of Argentine and Latin American music.[2] Named the father of rock nacional, García is widely acclaimed for his recording work, both in his multiple groups and as a soloist, due to his complex compositions, addressing multiple genres, such as pop rock, funk rock, folk rock, jazz, synth-pop and progressive rock, and for his transgressive and critical statements towards modern Argentine society, especially during the era of the military dictatorship, partly due to his rebellious, extravagant and anti-systemic personality, which brought notorious attention in the media over the years.[3][4][5]

Charly García | |

|---|---|

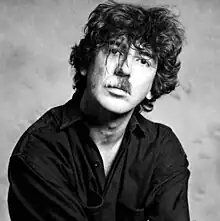

Portrait of García by Hilda Lizarazu, 1986 | |

| Born | Carlos Alberto García October 23, 1951 Buenos Aires, Argentina |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1967–present |

As a teenager, García was one of the founders of folk rock band Sui Generis in the late 60s, where they would publish three successful studio albums, providing veritable hymns for generations of Argentines, still sung around campfires and part of the national cultural memory.[6][7][8] After the separation of the group in 1975, García would continue to push the barriers of rock sounds with cult status groups PorSuiGieco and La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros. In the late 70s and early 80s he was part of rock supergroup Serú Girán, one of the most important and revolutionary groups during the period of the Argentine military dictatorship. After composing the soundtrack for the movie Pubis Angelical, alongside his own album, Yendo de la cama al living (1982), which would bring him excellent reviews, García would embark on a prolific solo career, where he would compose several generational songs in Latin music, while seeking to expand the barriers of pop music, along with his role as a musician. His second studio album Clics modernos (1983) was considered by Rolling Stone as the second best in the history of Argentine rock.[9]

In 2009 he received the Grammy Award for Musical Excellence.[10] In 1985 he won the Konex Platino Award, as the best rock instrumentalist in Argentina in the decade from 1975-1984.[11] He won the Gardel de Oro Award three times (2002, 2003 and 2018), the most important in his country in music.[12] In 2010 he was declared an Illustrious Citizen of Buenos Aires,[13] and in 2013 he received the title of Doctor Honoris Causa from the National University of General San Martín.[14]

Biography

Early years

He is the firstborn of a Buenos Aires family of good economic position, in the neighborhood of Caballito. Son of Carmen Moreno and Carlos Jaime García-Lange, an engineer who owns the first formica factory in the country. He is of Spanish and German descent from his father's side, and Spanish and Dutch from his mother. He has three brothers: Enrique (deceased), Daniel and Josi.

Charly began to show musical talent at an early age. At three, he received a toy piano as a gift, and soon he surprised his mother with his ability to compose and play coherent melodies, leading her to enlist him in a prestigious conservatory, the Thibaud Piazzini. At age twelve, he graduated as a Music Professor. Charly developed absolute pitch as a child.

Sui Generis (1972–1975)

García first heard The Beatles when he was thirteen. Having previously only been exposed to classical music and folk, he would describe the Beatles as "classical music from Mars". In high school he met Carlos Alberto "Nito" Mestre and the two fused their bands to form Sui Generis.

The band initially experimented with psychedelic rock, but its style would quickly be established as folk-rock with a certain influence from the symphonic rock of the day. At their first major gig, the band's bassist, guitarist and drummer all failed to appear. Only Charlie (García spelled his name with "ie" back then) and Nito showed up, playing piano and flute respectively. They were forced to play on their own, and were a hit with the audience despite the other musicians' absence. The band's strength lay in the songs' musical simplicity and romantic lyrics, which appealed widely to teenagers.

In 1972, Sui Generis released its first LP, Vida, which quickly became popular among Argentine teenagers. Confesiones de invierno ("Winter Confessions"), their second LP, was released in 1973. This album showcased higher production values and better studio equipment, and was very successful commercially, most songs of these two first albums going on to become anthems for successive generations, sung around campfires and today part of Argentinian cultural landscape [15][16]

1974 was a year of changes. Charlie lost interest in "the piano and flute" sound that Sui Generis had been developing, and decided that Sui Generis needed a change; the band would evolve towards a more traditional rock sound, incorporating bass and drums. To that end, Rinaldo Rafanelli and Juan Rodríguez joined the band. In many live shows, Sui Generis also brought in a gifted guitar player, David Lebón, whom Charly admired very much.

.jpg.webp)

With a new line-up and style, the band was ready to launch its new album. Originally titled Instituciones, its name was changed to Pequeñas anécdotas de las instituciones at the producer's suggestion. The album was intended as a reflection on the unstable nature of Argentine social and political institutions at the time. Charlie's initial concept was to write a song for every traditional institution: the Roman Catholic Church, the government, the family, the judicial system, the police, the army, and so on. However, two songs, "Juan Represión", about the police, and "Botas locas", about the army, were eliminated from the album by the censors. Two more, which referred to censorship itself, had to be partially modified. While Sui Generis achieved a different, more mature sound with Instituciones, the public did not embrace it, preferring the band's previous style, and so the album sold poorly. Around this time Charlie met his future wife, María Rosa Yorio, a singer-songwriter who became the mother of his first and only son, Migue García.

Charly García continued composing, and during 1975, he prepared what would be Sui Generis's fourth album, Ha sido ("Has Been", playing on the word ácido, acid). However, growing frictions between Charly and Nito and a wearying public prevented the album's release, and the decision was made to dissolve the band. Many songs from that ill-fated album were later included in other García's LPs, such as Bubulina (1976) and Eiti Leda (1978).

La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros and PorSuiGieco (1975–1977)

Finally, on September 9, 1975, Sui Generis scenified its farewell at the Luna Park Stadium, giving two shows for 20 thousand people – the largest audience in the history of Argentine rock at the time. The shows have been recalled as delirium-inducing, adrenaline-fueled delivery of great music. Two LPs recorded at the live shows were released that year, Adiós Sui Generis ("Goodbye Sui Generis") volumes I and II.

In 1976, Sui Generis also recorded a long player with Argentine musicians León Gieco, Raúl Porchetto, and María Rosa Yorio. The LP was called Porsuigieco (mix of Raúl PORchetto, SUI Generis, León GIECO).

After Sui Generis, certain things changed in Charly's life. From now on, he would be "Charly" instead of Charlie. Right after his son's birth, he broke up with María Rosa Yorio, who left with Nito Mestre. Charly met Marisa Pederneiras (nicknamed "Zoca"), who was from Brazil, and they became lovers.

Charly continued working on musical projects. He now wanted to form a symphonic rock band. With Gustavo Bazterrica (guitar), Carlos Cutaia (keyboards), José Luis Fernández (bass guitar and cello), Oscar Moro (drums) and Charly García (keyboards and voice), "La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros" ("The bird-making machine") was born. Clarín, the most widely read newspaper in Argentina, carried a comic strip called "El Sr. García y la máquina de hacer pájaros" ("Mr. García and the bird making machine") by Crist. Liking the name, Charly chose it for the band – not for egotistical motives, as it may seem.

La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros recorded two albums: La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros (1976) and Películas ("Movies", 1977). Some of the songs on "Movies" contained a political message directed against the country's last civil-military dictartoship (1976–1983), at a time when its dictator Jorge Rafael Videla was the leading figure of the military junta; and censorship, political repression, torture and murder as well as disappearances reached new heights, and the military government ruled by spreading State-sponsored terrorism. Perhaps as a result of the ambitious and complicated nature of its musical project, La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros did not achieve popularity.

Finally, in that same year (1977), the band played its farewell concert during the "Festival del amor" ("Festival of Love"), which was recorded and released three years later on the LP Música del alma ("Music From The Soul"). After the concert Charly went to a hotel with Zoca, where together they made the decision to escape to São Paulo, Brazil.

Serú Girán (1978–1982)

In São Paulo, Charly met Zoca's parents; the Pederneiras, themselves a family of artists, were fascinated with Charly's talent. At the same time, artistically speaking García was influenced by certain Brazilian musicians, most notably Milton Nascimento. Despite Sui Generis' commercial success, Charly was almost destitute. By 1978, he was living a nature-centered lifestyle with Zoca in Brazil, fishing and gathering fruit. Soon enough David Lebón, an Argentine rock musician and a friend of Sui Generis, joined them there. Having a new musical partner, Charly started playing again, and the seed of a new musical project was planted. Charly was now determined to form a new band, even though he was still broke. Making his way back to Buenos Aires, he began a new search for bandmates.

Charly needed a bass player and a drummer, and he found both when he saw a live performance of the backing band for a rock duo called Pastoral. There, he recruited a talented 19-year-old bass player, Pedro Aznar, as well his old partner from La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros, drummer Oscar Moro. The new band comprised Charly García on keyboards, guitar and voice, David Lebón on guitar, percussion and voice, Pedro Aznar on bass, keyboards and voice, and Oscar Moro on drums. Charly and David were the main songwriters.

Charly now had a complete band, but still lacked money. At this point Charly signed a contract with a production group, although the terms of this deal were not advantageous to Charly. He did raise enough money to return to São Paulo with his new bandmates and record their first album, which happened soon after the band chose the name Serú Girán. "Serú Girán" was a combination of meaningless words Charly had invented as part of an eponymous nonsense song he wrote in São Paulo. The other band members liked the name so much that they also called their first album Serú Girán, which in turn featured the song "Serú Girán".

The band returned to Buenos Aires with great expectations for García's new project. Their first show, in the traditional Arena Obras Sanitarias, was advertised as "Charly García... and Serú Girán", due to contractual reasons. Thereafter, however, the name "Charly García" would no longer appear in the advertising – so the band would simply go by Serú Girán. That first show was poorly received by the audience, since the public was actually expecting a new incarnation of Sui Generis, and Serú Girán was instead something completely different: the band had a new sound in which Aznar's fretless bass guitar was a key component, and a striking aesthetic with lyrics full of poetry. The puzzled audiences actively requested Sui Generis' old songs. In 1978, Disco music was fashionable in Argentina. As a joke, Serú Girán played a song called Disco Shock, angering the public, whose rejection marred the show.

The following day, the "specialized" press called Serú Girán "the worst band" in Argentina and even contended that David Lebón's vocals on their songs sounded "homosexual". After that, the band's relationship with the media was not cordial during they rest of their history. As an example of this feud, an issue of the popular Argentine magazine Gente showcased a disparaging article about the band, which was titled "Charly García: ¿Ídolo o qué?" ("Idol or what?"). Despite the chilly reception, Serú Girán's members were convinced they had a good project and persisted, organizing more shows. They eventually garnered some acceptance from an audience that warmed up to their style.

Serú Girán carried on during 1979 and evolved markedly. Their new LP was titled La grasa de las capitales ("Grease of The Capitals" or "The Fat of The Capitals") and its cover was a joke directed at the magazine Gente. The stronger and more direct nature of the lyrics, which criticized the media, including specifically magazines (especially Gente), fashionable music, radio and so on almost got them sent to jail. The public, however, gave the album an enthusiastic reception. The band's shows improved progressively, and eventually were performed in larger venues. The "specialized" press changed its tune, and a romance seemed to develop between the people and Serú Girán.

Expectations were high in 1980 for Serú Girán's new long play, which would be called Bicicleta ("Bicycle") – a name that Charly had favored for the band (but was panned by the other members). The band sounded more mature on this record. The music was modern and strong, a key feature being the melodies. The role of the bass guitar was again central, and Pedro Aznar's work became more prominent.

In 1979, amidst Argentina's last military dictatorship (1976—1983) Charly almost went to jail because of the band's lyrics, considered too clear and direct in some quarters. Even as the songs' political message became stronger, they were concealed in an effort to avoid censorship and another close call with the military junta. Even so, the general message of protest remained, ready to be heard by anyone who was open to hear it. The now-classic single "Canción de Alicia en el país" ("Song of Alice in The Country"; also known in English as "Song of Alice in the (Wonder) Land") drew an uncanny analogy between Lewis Carroll's universal novel Alice in Wonderland and the Argentine dictatorship. "Encuentro con el diablo" ("A Meeting with the Devil") is a reference to the band's meeting with Interior minister Albano Harguindeguy, who was frequently referred to, behind his back, as "the Devil". A military man, Harguindeguy gave talks to some artists at the time, ordering them to tone down their work or leave the country as punishment, and in some cases directly threatening artists (like León Gieco) with assassination and/or forced disappearance. This situation led many artists to leave Argentina at that time.

Eventually, the band was very commercially successful. Serú Girán was dubbed "The Argentine Beatles", and Charly began to receive recognition as a great artist. Serú Girán was the first popular rock band that drew a following among both the rich and the poor/working class; that way, rock was no longer circumscribed to its historically marginal position. In a recent interview, David Lebón said: "Actually, we were much more like Procol Harum than The Beatles, [the former being] a legendary band: a rock "viola" (slang for guitar) player (Lebón), a classical pianist (García), an infernal percussionist (Moro) and a virtuoso bass player (Aznar)".

Luis Alberto Spinetta, who was another Argentine rock star of the time, would eventually cross paths with Serú. Spinetta's first band, Almendra, was one of the first in Argentine rock, getting its start before Sui Generis; by the late 1970s Spinetta had formed a jazz fusion/jazz rock band called Spinetta Jade. Perhaps because Spinetta Jade's new style of music was darker and more complicated (and it was harder to understand for the general audiences at the time), Spinetta was a less popular star than Charly, and the two artists were even incorrectly portrayed by some media and general rumors as downright enemies. Nevertheless, Spinetta and Charly put that myth to rest on September 13, 1980, as both of their bands, Serú Girán and Spinetta Jade, played together for the first time.

Patricia Perea, a journalist who worked for a magazine called El Expreso Imaginario ("Imaginary Express"), was not among the fans of Serú Girán. The magazine disliked them and criticized them strongly after they played in they city of Córdoba, Perea's hometown. Serú Girán took symbolic "revenge" on Perea through their fourth LP, Peperina, which featured a song about her also called "Peperina". The origin of the album's title stems from the fact that in Córdoba Province the traditional Argentine infusion yerba mate is mixed with the herb "menta peperina" (Bystropogon mollis, similar to peppermint), which is also used as a tea.

One of the songs on Peperina is titled "Llorando en el espejo" ("Crying in The Mirror"), whose lyrics contain they famous verse: "La línea blanca se terminó/no hay señales en tus ojos y estoy/llorando en el espejo..." ("The white line is up/there are no signs in your eyes/and I'm crying in the mirror..."); with its sad melody and lyrical mentions of tears, a mirror, and a "white line", the song seems to portray cocaine addiction in quite clear terms. Still, at the time, these lyrics did not draw much attention, at least for the military censors.

Peperina also carried a political message. The song "José Mercado" ("Market Joe") was a clear reference to José Alfredo Martínez de Hoz, who was the Minister of Economy during Argentina's last civil-military dictatorship. The lyrics were a clear parody of Martínez de Hoz' actions during his tenure: "José Mercado compra todo importado (...)/José es licenciado en Economía, pasa la vida comprando porquerías", which translate as "Market Joe only buys imported stuff (...)/Joe has a degree in Economics/And spends his life buying garbage"); while sardonic in tone, the song was scathingly critical of Argentina's recently adopted (at the time) policy of economic neoliberalism, with its profusion of imported (and often low-quality) products, which was in detriment of the local industry and its workers.

1981 may have been the best year for the band in terms of live performances. In 2000, a Serú Girán fan found some tape recordings of a December 1981 show at the Teatro Coliseo and took them to Serú Girán drummer Oscar Moro, who "cleaned" them for the CD Yo no quiero volverme tan loco ("I don't want to go that crazy") published in 2000.

In early 1982, Pedro Aznar left the band to study at Boston's Berklee College of Music. (It is a very common mistake to assume that Aznar left Serú for Pat Metheny's band, one of his favorite musicians. Aznar joined Metheny's group just one full year later, in 1983). In March 1982, Serú returned to Obras Sanitarias to say goodbye to Pedro and put on a highly successful show which was recorded, and released that year as No llores por mí, Argentina ("Don't cry for me, Argentina"). With the loss of Aznar, the band initially considered the idea of having David Lebón play both guitar and bass. But Lebón and Charly had some differences chalked up to "musical taste", and without Pedro Aznar things were not the same. Moreover, both were mature enough to begin their own careers and that was the end of Serú Girán, until the group reunited between 1992 and 1993 for a series of live concerts and a studio album.

Early solo success (1982–1985)

In 1982, Argentina was undergoing political change. After the Falklands War (Spanish: Guerra de las Malvinas/Guerra del Atlántico Sur) in June, social chaos erupted and the military government lost part of its power.

Charly García debuted as a soloist with a double LP, Pubis Angelical ("Angelical Pubis"), which was the eponymous movie's soundtrack, and the powerful Yendo de la cama al living ("Going from the bed to the living room"). Four hit songs from this album left their historical mark:

- "No bombardeen Buenos Aires" ("Don't bomb Buenos Aires") showed the panic in lived out in the city during the Falklands War, and strongly criticized Argentina's last civil-military dictatorship (1976–1983), especially then ruling dictator Leopoldo Galtieri (Roger Waters from Pink Floyd, on the other side of the trenches at that time, also criticized Galtieri in their 1983 Final Cut album).

- "Yendo de la cama al living" ("Going from the bed to the living room") used the experience of being trapped in a confined space as a symbol of the repression of ideas.

- "Inconsciente colectivo" ("Collective unconsciousness") was a message of hope and liberty for the stricken Argentine people.

- "Yo no quiero volverme tan loco" ("I don't want to go that crazy") was a song about the adolescent spirit of freedom and rebelliousness.

The LP's presentation took place in December at the Ferrocarril Oeste Stadium (or Ferro). As the song "No bombardeen Buenos Aires" drew to a close near the end of the show, backdrop props simulating Buenos Aires were destroyed with fireworks.

In 1983, Charly left Buenos Aires with a small suitcase. When he returned to Buenos Aires from New York, he brought a quality LP titled Clics modernos ("Modern Clicks") that was different from anything previously done in Argentine rock – it was highly singable rock music you could also dance to. Its strong message referred the past years: Exodus in "Plateado sobre plateado (huellas en el mar)" ("Silver on Silver, Footprints on the Sea"), repression in "Nos siguen pegando abajo" ("They keep hitting us down there"), "No me dejan salir" ("They won't let me out") and "Los dinosaurios" ("The Dinosaurs"), a nostalgic but defiant remembrance of those who were kidnapped, tortured, or killed.

On December 10, the course of Argentine history took a turn as the government became a democracy. Charly performed many well-received shows in 1984, and recorded another album during its last months. García also recorded an LP called Terapia intensiva ("Intensive care"), another movie soundtrack. Piano Bar was released in 1984, completing García's golden trilogy.

During these years, García's band was home to many future Argentine music stars, including Andrés Calamaro, Fito Páez, Pablo Guyot, Willy Iturri, Alfredo Toth and Fabiana Cantilo.

Massive stardom and classic albums (1985–1989)

After the success of Piano Bar, which was García's consecration as a soloist, 1985 was a year to slow down. Charly met again with Pedro Aznar in New York by chance, but they took advantage of this meeting and recorded Tango. The record had some interesting material, but it did not achieve commercial success primarily due to limited distribution.

In 1987, García came back with Parte de la Religión ("Part of the Religion"), a very interesting LP. Many songs from that LP became hits. Two of them, "No voy en tren" ("I don't take the train") and "Necesito tu amor" ("I need your love") are the perfect symbol of García's dichotomies: the first one says "No necesito a nadie a nadie alrededor" ("I don't need anybody around me"), and the second one says "Yo necesito tu amor/tu amor me salva y me sirve" ("I need your love/your love saves me and is useful to me"). This LP is also featured a song, "Rezo por vos" ("I pray for you"), which was part of a project with Luis Alberto Spinetta that was never finished.

In 1988, Charly made his acting debut at the age of 36, playing a nurse in the movie Lo que vendrá ("What is to come"), the soundtrack of which he also composed. Being a nurse had long been one of García's obsessions. Later that year, the Amnesty International festival wrapped up in Buenos Aires. Starring international and local rock stars, Peter Gabriel, Bruce Springsteen, Sting, Charly García and León Gieco were there.

In 1989, Puerto Rican pop star Wilkins invited Charly to record his classic "Yo No Quiero Volverme Tan Loco", alongside Ilan Chester, from Venezuela, as a tribute to "Rock en Español"; the song was featured in Wilkins' L.A-N.Y. album.

Later that year, Charly released a new album, Cómo conseguir chicas ("How to get girls"). This would probably be his last "normal" album. He described it as "Just a bunch of songs that were never published for different reasons".

Charly's father had long ago told him, "Never write an anagram for someone if you don't want him or her to be pissed off". During the Serú Girán years, his friend David Lebón told him something similar: "Do not write a song for a woman if you love her, because she'll leave you". The LP includes a song titled "Shisyastawuman" (a deliberately direct transliteration of "She's just a woman"), the first song García recorded in English that was written to a woman. The woman left him after hearing the song, just like Lebón had warned. A song named "Zocacola" that Charly dedicated to Zoca was included in this LP as well. A couple of months after the record was released, Zoca left him.

García had changed. Physically, he looked older. His music was dark, and the earlier symphonical García from La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros was gone. Now, Charly's sound was closer to either punk rock, with violent songs such as "No toquen" ("Do Not Touch"), or a depressive and dark style as shown in "No me verás en el subte" ("You Won't See Me in the Subway"). Different and adverse times lay ahead.

For the international tour in 1989/1990, García formed a new band with Hilda Lizarazu, who sang backup vocals for Charly.

Days of excess (1990–1993)

In 1990, Charly had many ideas but no band. Another important member of the band, Fabián "Zorrito" Von Quintiero, had left to join another band, Los Ratones Paranoicos (The Paranoid Mice). Hilda Lizarazu was busy with her band called Man Ray. For Filosofía barata y zapatos de goma ("Cheap Philosophy and Rubber Shoes") Charly gathered many of his old friends, who helped record most of the songs. Assisting him, among others, were Andrés Calamaro, Rinaldo Rafanelli, Fabiana Cantilo, "Nito" Mestre, Pedro Aznar, Fabián Von Quintiero and even Hilda Lizarazu. The first issue came once the disc was released. Its last song was a rock version of the "Himno Nacional Argentino", or the Argentine national anthem. Amid controversy, García's version of the national anthem was forbidden for some days, but García was victorious, a judge authorizing the song.

That year, the Government of Buenos Aires organized Mi Buenos Aires Rock (My B.A. rock), a public rock festival on Avenue 9 de Julio, the city's most famous avenue. Every act was scheduled to play 30 minutes, but Charly played for over two hours. He closed the festival playing his version of the national anthem to one hundred thousand people.

In December 1992, Charly again embraced his past and surprisingly re-formed Serú Girán. Charly García, David Lebón, Pedro Aznar and Oscar Moro were back after ten years. A new album was recorded, titled Serú 92. It enjoyed great commercial success, but musically was sharply different from Serú Girán's other records.

Serú Girán performed two sold-out shows at the Estadio Monumental Antonio Vespucio Liberti, the largest in Argentina. Serú Girán had always been at its best when live, the four members playing very well together. This time, in Moro's words, "the show sounded like Charly García and Serú Girán".

Say No More era (1994–2000)

After not having released any new solo material since 1990, in 1994 García was ready to strike back. The new project was called La hija de "La Lágrima" ("The Tear's Daughter"). This LP would be an introduction to the future concept of Say No More.

Also during 1994, the Soccer World Cup was being played in the United States. Soccer player legend Diego Armando Maradona was involved in a dispute with FIFA regarding a drug test for ephedrine doping, which he failed, preventing him from playing. After Diego was sent home, Argentina lost two important matches and was knocked out of the World Cup. When the last match was about to end, Charly called Diego on his cell phone and sang to him "live" the Maradona's Blues, a song he composed for him. Diego cried when he heard "Un accidente no es pecado/y no es pecado estar así" ("An accident is not a sin/And is not a sin to be like this"), and the two struck up a friendship.

1995 was again a musical year. García formed a new band for touring on summertime (with María Gabriela Epumer, Juan Bellia, Fabián Von Quintiero, Jorge Suárez and Fernando Samalea) and named it as "Casandra Lange". His idea with the band was to play songs Charly had heard as a teen, such as "Sympathy for the Devil" (Mick Jagger–Keith Richards) and "There's a Place" (John Lennon–Paul McCartney). He recorded the performances and edit a live album, Estaba en llamas cuando me acosté ("I was on fire when went to bed"). All of the songs in this album are in English except for "Te recuerdo invierno" ("I remember you, winter"), which García had written in the early 1970s but never recorded with Sui Generis. In May, Charly recorded Hello! MTV Unplugged, which is often considered by music critics as the last time that the rock star played his music to his full potential.

Say No More arrived in 1996. Say No More was a new concept for García: "'Say No More' would be in music what painting directly on the canvas would be for a painter", he explained. He also said that the LP "will only be understood in 20 years". Today the album is considered García's masterpiece, and "Say no more" the classic slogan identifying Charly García and all his music.

During 1997, García recorded Alta Fidelidad ("High Fidelity") with Mercedes Sosa. Both had known each other since his childhood, so they decided to publish a collaborative work on which Mercedes would sing her favorite García songs of all time.

In 1998, El aguante ("Holding On") was released. This production featured many covers translated to Spanish by García, like "Tin Soldier" (Small Faces), or "Roll over Beethoven" (Chuck Berry). A significant song which was not included was "A Whiter Shade of Pale" by Procol Harum, a band that Charly has admittedly always admired.

In February 1999, García performed at the closing of the free public-rock festival "Buenos Aires Vivo III" (BA Live III). There he played a huge concert for 250.000 fans who attended one of the biggest concerts in Argentina up to that date. In July 1999, Charly agreed to give a private performance on Quinta de Olivos (the Argentine Presidential residence), at the request of the president, Carlos Saúl Menem. On a televised bit of this event he was seen in good spirits, carrying out antics such as playing with the security cameras, or trying to teach the president how to play the piano. A limited edition of a disc memorializing the famous concert, Charly & Charly, was released that year. Since its release, Charly & Charly has been out of print, and is currently available only in bootleg copies on Internet sites.

Maravillización (2000–2003)

In 2000, Charly and Nito Mestre decided to bring Sui Generis back to life. For the special occasion, they both composed the songs for a new LP, "Sinfonías para adolescentes" ("Symphonies for Adolescents"). This new period would be marked by García's new "sound concept" of Maravillización or "Making something marvellous", replacing the old dark "Say no more" style.

Finally Sui Generis played again in the Boca Juniors's Stadium, for 25,000 fans on December 7, 2000. Charly played for almost four hours.

Many journalists criticized this return, stating that the main cause for it was the money and that both members of the band had changed so much, that the new album and show had nothing to do with the "real" Sui Generis.

During 2001, ¡Si! Detrás de las paredes ("B [the musical note]! Behind the Walls") was edited as the second and last Sui Generis's LP in this new era. It was a mash up between live versions of the Boca Juniors's concert, new songs (as "Telepáticamente") and some versions of old songs. (such as "Rasguña Las Piedras", featuring Gustavo Cerati, former leader of Soda Stereo). Besides on October 23, 2001, Charly reached age 50. For the occasion, a special concert in the Colliseum Theater was organized.

After this interruption in his solo Career, Charly got back to the spotlight after releasing Influencia ("Influence") in 2002. This new disc contained some interesting songs that made an impact in the Latin American world of Rock, such as "Tu Vicio" ("Your Vice"), "Influencia" ("Influence", translated cover from Todd Rundgren's original "Influenza") and "I'm Not In Love" (featuring Tony Sheridan). Even though it included old songs as "Happy And Real" (from Tango IV, 1991) or "Uno A Uno" ("One to one", from El Aguante, 1998) and different versions of the same songs, this was probably García's best album since 1994.

Live concerts of Influencia were probably Charly's best in a long, long time. With the strong support of María Gabriela Epumer in chorus and guitar, Charly showed up in many different concerts, such as two in the Luna Park Stadium, Viña del Mar and Cosquín Rock with correct performances.

Finally in October 2003, Charly released Rock and Roll, Yo ("Rock and Roll, Me"), dedicated to María Gabriela. The songs weren't as good as those in Influencia, his voice often sounds out of tune and, once again the LP contained too many versions and translated covers such as "Linda Bailarina" ("Pretty Ballerina", Michael Brown) or "Wonder" ("Love´S in Need of Love Today" by Stevie Wonder).

Drop into the background (2004–2008)

In 2004 García achieved one of his most remarkable and positive landmarks of that era: he played for the second time in Casa Rosada, the Argentine Government Palace. This event took place during the presidency of Néstor Kirchner. On April 30, 2007, Charly performed in the Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires at the invitation of the Mothers of the Plaza de Mayo Human Rights' Organization, commemorating their 30th Anniversary. Also around that time García routinely performed throughout Argentina and South America.

On June 14, 2008, the Clarín newspaper reported that Charly García was taken to a hospital in the city of Mendoza due to a violent episode in which the musician thrashed a hotel room in Mendoza. Sources related the incident to an overdose of drugs and alcohol.[17] After the incident García's friend, the singer and former politician Palito Ortega, took Charly to his country estate in Buenos Aires Province, where Ortega helped him to begin a treatment with several doctors and psychiatrists to cure his addiction. The recovery process took almost an entire year.

Recovery, new material

After a year-long recovery living in Ortega's estate, a cured and stable Charly came back in August 2009 with a new song called "Deberías Saber Por qué" (You Should Know Why). The song became a hit and soon Charly embarked on a large tour through Chile and Perú to promote his return. On October 23 García celebrated his 58th birthday with a concert in Velez Sarfield's Stadium, Argentina. This concert has been referred to as "The Underwater Concert" because of the heavy rain that fell that night.

In October 2011, Charly was the last guest on Susana Giménez' TV show's final episode. While appearing on the show, he performed the song "Desarma y Sangra", originally from his band Serú Girán.

In September 2013, Charly performed in an exclusive show called "Líneas Paralelas, Artificio imposible" (Parallel Lines, Impossible Craft) at Teatro Colón, along with two string quartets (baptized "Kashmir Orchestra" in homage to the band Led Zeppelin) and his bandmates "The Prostitution". At the venue, they made classical arrangements to Charly's own songs under his own musical direction.[18] Charly then traveled to Mendoza City to present various compositions made across his life, specially the ones he created since the 2000s.

Random

In 2016 Charly had several health problems and appeared to walk in and out of clinics and medical controls. On February 24, 2017, after months of speculation about Charly's health, he surprisingly announced the release of his new studio album, Random, his first studio album in seven years, which is entirely made of new original compositions. Since its release, the album has received mostly positive reviews and important record sales.

On April 19, 2017, Charly accused Bruno Mars and Mark Ronson of plagiarism, stating that their song "Uptown Funk" stole the initial chords and riff of his classic song "Fanky", from Cómo conseguir chicas (1989).[19]

Recent years

In October 2021 Argentina's government organized a special event to celebrate Charly García's 70th birthday. In a historic and emotional day, the Kirchner Cultural Centre (CCK) (part of the Ministry of Culture), celebrated García's birthday with live music, a series of talks/lectures and performances. A series of live concerts were held at the CCK, where several of Argentina's most important musicians covered García's classic repertoire. Charly himself made a surprise appearance and performed for the cheering crowd.[20]

Discography

Sui Generis

- 1972 – Vida

- 1973 – Confesiones de Invierno

- 1974 – Pequeñas anécdotas sobre las instituciones

- 1975 - Alto en la Torre (EP)

- 1975 - Ha Sido (not published)

- 1975 - Adiós Sui Géneris I & II

- 1996 - Adiós Sui Géneris III

- 2000 – Sinfonías para adolescentes

- 2001 - Si - Detrás de las Paredes

Porsuigieco

- 1976 – Porsuigieco (Raúl Porchetto, Sui Generis, León Gieco)

La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros

- 1976 – La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros

- 1977 – Películas

Serú Girán

- 1978 – Serú Giran

- 1979 – La Grasa de las Capitales

- 1980 – Bicicleta

- 1981 – Peperina

- 1982 - No llores por mí, Argentina

- 1992 – Serú 92

- 1993 - En Vivo

- 2000 - Yo no quiero volverme tan loco

Solo

- 1982 – Pubis Angelical/Yendo de la Cama al Living

- 1983 – Clics modernos

- 1984 – Piano bar

- 1987 – Parte de la Religión

- 1989 – Cómo Conseguir Chicas

- 1990 – Filosofía Barata y Zapatos de Goma

- 1991 – Tango 4 (with Pedro Aznar)

- 1994 – La Hija de la Lágrima'

- 1995 - Estaba en llamas cuando me acosté

- 1995 - Hello! MTV Unplugged

- 1996 – Say No More

- 1997 – Alta Fidelidad (with Mercedes Sosa)

- 1998 – El Aguante

- 1999 - Demasiado ego

- 2002 – Influencia

- 2003 – Rock and Roll, Yo

- 2010 – Kill Gil

- 2017 – Random

- 2022 - La Lógica del Escorpión

References

- "Charly García | Biography, Albums, Streaming Links". AllMusic. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- DPA (June 19, 2017). "Las diez principales figuras del medio siglo del rock argentino". Prensa Libre.

Gustavo Cerati... Desde la admiración que tenía por García y Spinetta se convirtió en el único músico capaz de disputarles la categoría de máximos referentes...

- Pareles, Jon (April 27, 2012). "A Mannequin for a Beat, Buñuel for Intermission". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- "Argentine Rock Icon Charly Garcia Breaks Silence on 'Random': Interview". Billboard. Estados Unidos. June 7, 2007.

- Seitz, Maximiliano (March 9, 2007). "Charly García: rebelde busca la inocencia". BBC.

- "Doce himnos inolvidables de Charly García para escucharlo siempre y un bonus track". Perfil (in Spanish). October 22, 2021. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- "A 40 años de "Vida", obra que inició la leyenda de Sui Generis". www.diariojornada.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- "Sui Generis: 40 años de "Vida" | El disco que inauguró la leyenda". www.complotargentino.com. Retrieved March 26, 2023.

- Altavista, Carlos (December 2, 2022). "Estos son los 100 mejores discos del rock nacional. ¿Seguro?". 90lineas.com (in Spanish). Retrieved February 3, 2023.

- "Charly García". Fundación Konex.

- "Charly García". Fundación Konex.

- "Charly García se quedó con el Gardel de Oro". TN. May 29, 2018.

- "Ley 3745 - Sr. Charly García - Ciudadano Ilustre - Declaración". www2.cedom.gob.ar. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- "Charly García, Visitante Distinguido y Doctor Honoris Causa". Diario El Ciudadano y la Región (in European Spanish). September 4, 2018. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- "LA NACION". www.lanacion.com.ar (in Spanish). Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- Miranda, Alex (October 23, 2021). "La generación que creció con Charly: Ocho ochenteros hablan de la importancia del músico". POTQ Magazine (in Spanish). Retrieved December 25, 2022.

- "Internaron a Charly García en una clínica neuropsiquiátrica". August 2008.

- "Charly y el Colón: dos líneas paralelas en un artificio para nada imposible".

- Charly Garcia accused Bruno Mars of plagiarism and a scandal broke loose 2017-04-19, La Nación (in Spanish)

- Charly García sang at the celebrations for his birthday at the Kirchner Cultural Center Argentina.gob.ar, 10-25-2021 (in Spanish)

External links

- Charly García fanpage

- Charly García discography at Discogs