Chebyshev filter

Chebyshev filters are analog or digital filters that have a steeper roll-off than Butterworth filters, and have either passband ripple (type I) or stopband ripple (type II). Chebyshev filters have the property that they minimize the error between the idealized and the actual filter characteristic over the operating frequency range of the filter,[1][2] but they achieve this with ripples in the passband. This type of filter is named after Pafnuty Chebyshev because its mathematical characteristics are derived from Chebyshev polynomials. Type I Chebyshev filters are usually referred to as "Chebyshev filters", while type II filters are usually called "inverse Chebyshev filters".[3] Because of the passband ripple inherent in Chebyshev filters, filters with a smoother response in the passband but a more irregular response in the stopband are preferred for certain applications.[4]

| Linear analog electronic filters |

|---|

Type I Chebyshev filters (Chebyshev filters)

.svg.png.webp)

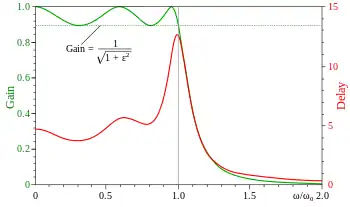

Type I Chebyshev filters are the most common types of Chebyshev filters. The gain (or amplitude) response, , as a function of angular frequency of the th-order low-pass filter is equal to the absolute value of the transfer function evaluated at :

where is the ripple factor, is the cutoff frequency and is a Chebyshev polynomial of the th order.

The passband exhibits equiripple behavior, with the ripple determined by the ripple factor . In the passband, the Chebyshev polynomial alternates between -1 and 1 so the filter gain alternate between maxima at and minima at .

The ripple factor ε is thus related to the passband ripple δ in decibels by:

At the cutoff frequency the gain again has the value but continues to drop into the stopband as the frequency increases. This behavior is shown in the diagram on the right. The common practice of defining the cutoff frequency at −3 dB is usually not applied to Chebyshev filters; instead the cutoff is taken as the point at which the gain falls to the value of the ripple for the final time.

The 3 dB frequency is related to by:

The order of a Chebyshev filter is equal to the number of reactive components (for example, inductors) needed to realize the filter using analog electronics.

An even steeper roll-off can be obtained if ripple is allowed in the stopband, by allowing zeros on the -axis in the complex plane. While this produces near-infinite suppression at and near these zeros (limited by the quality factor of the components, parasitics, and related factors), overall suppression in the stopband is reduced. The result is called an elliptic filter, also known as a Cauer filter.

Poles and zeroes

.svg.png.webp)

For simplicity, it is assumed that the cutoff frequency is equal to unity. The poles of the gain function of the Chebyshev filter are the zeroes of the denominator of the gain function. Using the complex frequency , these occur when:

Defining and using the trigonometric definition of the Chebyshev polynomials yields:

Solving for

where the multiple values of the arc cosine function are made explicit using the integer index . The poles of the Chebyshev gain function are then:

Using the properties of the trigonometric and hyperbolic functions, this may be written in explicitly complex form:

where and

This may be viewed as an equation parametric in and it demonstrates that the poles lie on an ellipse in -space centered at with a real semi-axis of length and an imaginary semi-axis of length of

The transfer function

The above expression yields the poles of the gain . For each complex pole, there is another which is the complex conjugate, and for each conjugate pair there are two more that are the negatives of the pair. The transfer function must be stable, so that its poles are those of the gain that have negative real parts and therefore lie in the left half plane of complex frequency space. The transfer function is then given by

where are only those poles of the gain with a negative sign in front of the real term, obtained from the above equation.

The group delay

The group delay is defined as the derivative of the phase with respect to angular frequency and is a measure of the distortion in the signal introduced by phase differences for different frequencies.

The gain and the group delay for a 5th-order type I Chebyshev filter with ε=0.5 are plotted in the graph on the left. It can be seen that there are ripples in the gain and the group delay in the passband but not in the stopband.

Setting the cutoff attenuation

Pass band cutoff attenuation for Chebyshev filters is usually the same as the pass band ripple attenuation, set by the computation above. However, many applications such as diplexers and triplexers, require a cutoff attenuation of -3.0103 dB in order to obtain the needed reflections. Other specialized applications may require other specific values for cutoff attenuation for various reasons. It is therefore useful to have a means available of setting the Chebyshev pass band cutoff attenuation independently of the pass band ripple attenuation, such as -1 dB, -10 dB, etc. The cutoff attenuation is set by frequency scaling the denominator of the transfer function. This can be approximated by interpolating Chebyshev filter cutoff attenuation tables, or calculated precisely with Newton's method.

The denominator may be frequency scaled by using a scaling factor that we will refer to as . The frequency scaled denominator of the Chebyshev transfer function may be rewritten for the case in terms of frequency scaling variable as follows:

The task for modifying to is to find an that results in the desired attenuation at 1 radian/s for the normalized transfer function. Newton's method can be easily summarized to do this by its basic definition:

through successive iterations of until is the frequency that attenuates to the desired attenuation at 1 radian/s.

While the above summary may be concise and easily understood, the mechanics of obtaining an accurate derivative of the magnitude function along the axis may be problematic. Digital techniques may be used, but it is generally better to apply Newton's method with continuous functions, if possible, so as to maximize accuracy. Therefore, it is useful to modify the expression to eliminate excess mathematical functions by making the following alterations:

1) Multiply by to obtain . This will eliminate complex numerical results when evaluating by removing the odd order terms in the polynomial.

2) In , negate all terms of when is divisible by 4. That would be , , , and so on. We will call the modified function , and this modification will allow the use of real numbers instead of complex numbers when evaluating the polynomial and its derivative. That is, we can now use the real in place of the complex

3) Convert the desired attenuation in dB to an arithmetic value using . For example, -3.0103 dB is .7071, -1 dB is .8913 ans so on. This simplifies the derivative evaluation.

4) Square the resulting arithmetic attenuation to correlate with the squaring of the function.

5) Calculate the modified in Newton's method using the real value, . Always take the absolute value.

6) Calculate the derivative the modified with respect to the real value, . Negate the derivative computation to account for the effects due to the modifications made to create . DO NOT take the absolute value of the derivative.

When steps 1) through 4) are compete, Newton's method expression my be written:

using a real value for with no complex arithmetic needed. The movement of should be limited to prevent it from going less than 1 radian/s and into the ripple frequencies early in the iterations for increased reliability. When complete, invert to obtain an that can be used to scale the original transfer function denominator. The attenuation of will then be virtually the exact desired value at 1 radian/s. If performed properly, only a handful of iterations are needed to set the attenuation through a wide range of desired attenuation values for both small and very large order Chebyshev filters.

Type II Chebyshev filters (inverse Chebyshev filters)

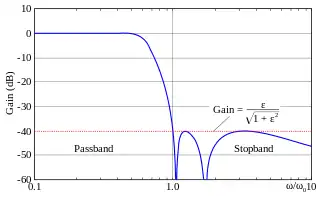

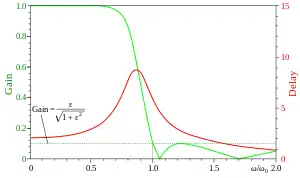

Also known as inverse Chebyshev filters, the Type II Chebyshev filter type is less common because it does not roll off as fast as Type I, and requires more components. It has no ripple in the passband, but does have equiripple in the stopband. The gain is:

In the stopband, the Chebyshev polynomial oscillates between -1 and 1 so that the gain will oscillate between zero and

and the smallest frequency at which this maximum is attained is the cutoff frequency . The parameter ε is thus related to the stopband attenuation γ in decibels by:

For a stopband attenuation of 5 dB, ε = 0.6801; for an attenuation of 10 dB, ε = 0.3333. The frequency f0 = ω0/2π is the cutoff frequency. The 3 dB frequency fH is related to f0 by:

Poles and zeroes

.svg.png.webp)

Assuming that the cutoff frequency is equal to unity, the poles of the gain of the Chebyshev filter are the zeroes of the denominator of the gain:

The poles of gain of the type II Chebyshev filter are the inverse of the poles of the type I filter:

where . The zeroes of the type II Chebyshev filter are the zeroes of the numerator of the gain:

The zeroes of the type II Chebyshev filter are therefore the inverse of the zeroes of the Chebyshev polynomial.

for .

The transfer function

The transfer function is given by the poles in the left half plane of the gain function, and has the same zeroes but these zeroes are single rather than double zeroes.

The group delay

The gain and the group delay for a fifth-order type II Chebyshev filter with ε=0.1 are plotted in the graph on the left. It can be seen that there are ripples in the gain in the stopband but not in the pass band.

Implementation

Cauer topology

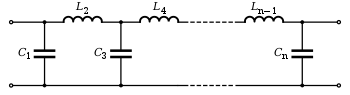

A passive LC Chebyshev low-pass filter may be realized using a Cauer topology. The inductor or capacitor values of an th-order Chebyshev prototype filter may be calculated from the following equations:[5]

G1, Gk are the capacitor or inductor element values. fH, the 3 dB frequency is calculated with:

The coefficients A, γ, β, Ak, and Bk may be calculated from the following equations:

where is the passband ripple in decibels. The number is rounded from the exact value .

The calculated Gk values may then be converted into shunt capacitors and series inductors as shown on the right, or they may be converted into series capacitors and shunt inductors. For example,

- C1 shunt = G1, L2 series = G2, ...

or

- L1 shunt = G1, C1 series = G2, ...

Note that when G1 is a shunt capacitor or series inductor, G0 corresponds to the input resistance or conductance, respectively. The same relationship holds for Gn+1 and Gn. The resulting circuit is a normalized low-pass filter. Using frequency transformations and impedance scaling, the normalized low-pass filter may be transformed into high-pass, band-pass, and band-stop filters of any desired cutoff frequency or bandwidth.

Digital

As with most analog filters, the Chebyshev may be converted to a digital (discrete-time) recursive form via the bilinear transform. However, as digital filters have a finite bandwidth, the response shape of the transformed Chebyshev is warped. Alternatively, the Matched Z-transform method may be used, which does not warp the response.

Comparison with other linear filters

The following illustration shows the Chebyshev filters next to other common filter types obtained with the same number of coefficients (fifth order):

Chebyshev filters are sharper than the Butterworth filter; they are not as sharp as the elliptic one, but they show fewer ripples over the bandwidth.

See also

References

- Daniels, Richard W. (1974). Approximation Methods for Electronic Filter Design. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-015308-6.

- Lutovac, Miroslav D.; Lutovac, D.; Tošić, Dejan V.; Evans, Brian Lawrence (2001). Filter Design for Signal Processing Using MATLAB and Mathematica. Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780201361308.

- Weinberg, Louis; Slepian, Paul (June 1960). "Takahasi's Results on Tchebycheff and Butterworth Ladder Networks". IRE Transactions on Circuit Theory. 7 (2): 88–101. doi:10.1109/TCT.1960.1086643.

- Williams, Arthur B.; Taylors, Fred J. (1988). Electronic Filter Design Handbook. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-070434-1.

- Matthaei, George L.; Young, Leo; Jones, E. M. T. (1980). Microwave Filters, Impedance-Matching Networks, and Coupling Structures. Norwood, MA: Artech House. ISBN 0-89-006099-1.

External links

Media related to Chebyshev filters at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Chebyshev filters at Wikimedia Commons