Cherokee funeral rites

Cherokee funeral rites comprise a broad set of ceremonies and traditions centred around the burial of a deceased person which were, and partially continue to be, practiced by the Cherokee peoples.

Preparing for death

In some communities, when a father knew he would soon die he called for his children to gather around him and then gave them advice and knowledge to keep with them for the rest of their lives. When the father was about to die, the children would leave and only adult family members and a priest would stay with him.[1] In another tradition, if an individual knew they were near death they would walk as far away from the village as possible, lie down, and die. If they were later found by another community member, that individual would cover the body with rocks.[2]

Shamans were largely responsible for healing and medicine, so they tended to the sick before death and were deeply involved in the dying process. In addition to their healing abilities, shamans had deep knowledge of death and life which was believed to help them prevent death, aid individuals in their transition to death, and protect the dying person from dangerous spiritual figures and magic such as the Raven Mocker. In some communities, a vigil would be held starting just before death and continuing until the burial.[2][3]

Burial

Body preparation

Bodies were prepared for burial immediately after death.[2] A close relative of the deceased would close the eyelids and clean the body with either water or a wash made by boiling willow root, both of which were considered purifying substances.[1] In communities where bodies were not buried nude, the body was dressed in “dead clothes,” which were prepared in early adulthood and stored until burial.[2]

Burial elements

Bodies were predominantly buried in the ground, however less commonly the Cherokee would lay their dead in caves. Burial practices varied depending on location, time, and the status of the deceased individual. In early Cherokee culture, following the tradition of the Mississipian civilization that preceded the Cherokee, when a chief died individuals who were close to him were killed and buried with him, including his wives and some of his servants. The purpose of this practice was to sever all of the chief’s ties to the physical world on earth so that he may freely enter the spirit world. In patriarchal settings, some members of a man’s immediate family would be sacrificed and buried with him. As the distribution of power between men and women became more equal and Cherokee social and power structures shifted towards a matrilineal and more matriarchal system, these customs of sacrifice became obsolete. Priests and spiritual advisors were honoured at their burial by the sacrifice of their slaves, who were impaled and situated in a circle around the priests' graves. This ensured the slaves would continue to watch over and care for the priest in death.[2]

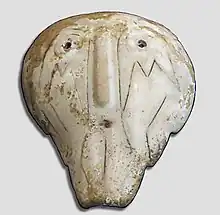

The Cherokee mostly used shallow graves that were not much larger than the body. Bodies were often laid in the fetal position, possibly due to the belief that one should rest in death in the earth as they once rested within their mother. Most Cherokee were buried with items of personal importance. Excavations of burial sites at Garden Creek Mound in North Carolina have found items including pottery, metal and bone ornaments, shells, and ceramics. Hairpins, beads, and pendants have also been found in graves.[2] In some regions, shell masks have been found in many graves, mainly in those of men. These masks do not appear to have been worn during life and were likely made specifically to be buried with the individual. Markings of falcon eyes and thunderbolts indicate these masks may be spiritually related to the Thunderbird figure, who was a powerful warrior and aided humans in warfare and hunting.[4] These masks, along with other grave goods, are usually placed near the individual’s head. Food and water was often also buried with the body so as to provide the spirit with nourishment and energy as they travel to the spirit world.[2]

Each community had a priest who was responsible for burying the dead. Soon after death, the priest would come to the home of the deceased, where most deaths occurred. In some communities, it was most common for individuals to be buried under the floor in their home where they had died, under the hearth in the home, or outside near the home. In other communities, it was more common for individuals to be buried outside. In these cases, a male relative would help the priest move the body to where it would be interred.[1] The Cherokee commonly believed that if an individual died before sunrise, they should be buried before sundown, and if they died before sundown, they should be buried before sunrise.[2]

Burial mounds

Bodies that were buried outside were covered with rocks and dirt, and then later covered by other dead bodies, which would also be covered with rocks, dirt, and other bodies. These piles of bodies would eventually form large burial mounds. New burial mounds were started when a priest died.[2] In some instances bodies were placed on an elevated, exposed surface and then covered with stones, creating stone heaps that were at least four to five feet high.[5]

Rituals after death

The Cherokee traditionally observed a seven day period of mourning. Seven is a spiritually significant number to the Cherokee as it is believed to represent the highest degree of purity and sacredness. The number seven can be seen repeatedly across Cherokee culture, including in the number of clans, and in purifying rituals after death.[6] During the seven day mourning period, family members of the deceased were to remain solemn, never angering or creating tension, and only consumed simple and light food and drink. The intensity of the expression of grief was determined by the circumstances of the death.[1]

On the first night after the death, the family was invited to the town council house where they were greeted and consoled by other community members. Then, the family would either return home or stay while the community performed a solemn dance.[1]

On the morning of the fifth day of mourning, family members gathered around the priest who took a bird that had been killed by an arrow, plucked some feathers from it, and cut a small piece of meat from its right breast. He would then pray and throw the meat into fire.[1]

On the final two days of mourning, family members and other mourners spent their morning at the water immersing themselves and then went to the grave site where the women would cry and wail to express their grief.[1]

While the women mourned at the grave on the last two days of the mourning period, the Chief Priest sent hunters to bring meat which the family, assisted by relatives and community members, would prepare for a community feast on the seventh night of mourning.[1] In some communities, this feast would happen before burial and the body would be laid out. The food that is buried with the body comes from this feast.[2]

Purification Rituals

When an individual died, their surviving family and everything in their home was considered unclean. Personal belongings that were not buried with the deceased were often burned at the grave site. Fire is sacred to the Cherokee and after a death, it is used to purify the uncleanliness that remains.[6] A priest would perform a ritual to cleanse the house and the hearth soon after death. He would then kindle a new fire and place his medicine pot filled with water on it. In the pot, he would boil a tea and give it to the family, who would purify themselves by drinking and washing themselves in it. The priest would also smoke inside the home and burn a fire with cedar boughs and purifying weeds. Lastly, he would take the unclean family members to a river or creek, where they would enter the water, turn between facing east and west, and immerse themselves seven times. After leaving the water, they would put on new clothes and return to their home clean.[1]

Modern practices

In the present day, many traditional Cherokee funeral traditions persist. Cherokee communities often continue to hold community feasts where they grieve and celebrate the life they have lost; to practice vigil prayers to help the deceased’s spirit find its way to the spirit world; and to bury individuals with valued personal belongings. Some traditions are still culturally important to Cherokee communities however they are limited by laws of the settler state. For example, many American states do not permit spiritual advisors to remain with the body from death until burial.[2]

A large percentage of Cherokee individuals today are Christians and engage in Christian funeral practices. These funerals usually do not contain elements of traditional Cherokee funeral practices, however in many cases they are held in both English and Cherokee languages. Additionally, it is common in Christian Cherokee communities for burial to happen on the deceased’s homestead instead of at a cemetery.[2]

References

- Mails, Thomas E. (1992). The Cherokee People: The Story of the Cherokees from Earliest Origins to Contemporary Times. Tulsa, Oklahoma: Council Oak Books. pp. 76–78. ISBN 0-933031-45-9.

- Burley-Jones, Tracy (2002). "The Death System in Tsalagi Culture". Totem: The University of Western Ontario Journal of Anthropology. 10 (1): 20–26.

- Irwin, Lee (Spring 1992). "Cherokee Healing: Myth, Dreams, and Medicine". American Indian Quarterly. 16 (2): 237–257. doi:10.2307/1185431. JSTOR 1185431 – via JSTOR.

- Smith, Marvin T.; Smith, Julie Barnes (Summer 1989). "Engraved Shell Masks in North America". Southeastern Archaeology. 8 (1): 9–18. JSTOR 40712894 – via JSTOR.

- Bushnell, David Ives (1920). "Native cemeteries and forms of burial east of the Mississippi". Bureau of American Ethnology. 71: 1–160. hdl:10088/15538 – via Smithsonian Research Online.

- Hudson, Charles (1976). The Southeastern Indians. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. pp. 120–183.