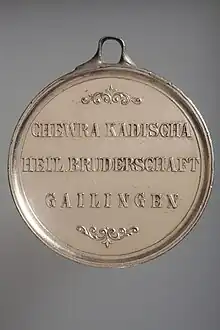

Chevra kadisha

The term chevra kadisha (Hebrew: חֶבְרָה קַדִּישָׁא)[1] gained its modern sense of "burial society" in the nineteenth century. It is an organization of Jewish men and women who see to it that the bodies of deceased Jews are prepared for burial according to Jewish tradition and are protected from desecration, willful or not, until burial. Two of the main requirements are the showing of proper respect for a corpse, and the ritual cleansing of the body and subsequent dressing for burial.[2] It is usually referred to as a burial society in English.

History

Throughout Jewish history, each Jewish community throughout the world has established a chevra kadisha – a holy society – whose sole function is to ensure dignified treatment of the deceased in accordance with Jewish law, custom, and tradition. Men prepare the bodies of men, women prepare those of women.[2]

At the heart of the society's function is the ritual of tahara, or purification. The body is first thoroughly cleansed of dirt, bodily fluids and solids, and anything else that may be on the skin, and then is ritually purified by immersion in, or a continuous flow of, water from the head over the entire body. Tahara may refer to either the entire process, or to the ritual purification. Once the body is purified, the body is dressed in tachrichim, or shrouds, of white pure muslin or linen garments made up of ten pieces for a male and twelve for a female, which are identical for each Jew and which symbolically recalls the garments worn by the High Priest of Israel. Once the body is shrouded, the casket is closed. For burial in Israel, however, a casket is not used in most cemeteries.

The society may also provide shomrim, or watchers, to guard the body from theft, vermin, or desecration until burial. In some communities this is done by people close to the departed or by paid shomrim hired by the funeral home. At one time, the danger of theft of the body was very real; in modern times the watch has become a way of honoring the deceased.

A specific task of the burial society is tending to the dead who have no next-of-kin. These are termed a meit mitzvah (מת מצוה, a mitzvah corpse), as tending to a meit mitzvah overrides virtually any other positive commandment (mitzvat aseh) of Torah law, an indication of the high premium the Torah places on the honor of the dead.

Many burial societies hold one or two annual fast days and organise regular study sessions to remain up-to-date with the relevant articles of Jewish law. In addition, most burial societies also support families during the shiva (traditional week of mourning) by arranging prayer services, meals and other facilities.

While burial societies were, in Europe, generally a community function, in the United States it has become far more common for societies to be organized by neighborhood synagogues. In the late 19th and early 20th century, chevra kadisha societies were formed as landsmanshaft fraternal societies in the United States. Some landsmanshaftn were burial societies while others were "independent" groups split off from the chevras. There were 20,000 such landsmanshaftn in the U.S. at one time.[3][4]

Recordkeeping

The chevra kadisha of communities in pre-World War II Europe maintained Pinkas Klali D’Chevra Kadisha (translation: general notebook of the Chevra Kadisha); some were handwritten in Yiddish, others in Hebrew.[5]

Etymology

In Hebrew, the phrase can be written חבורה קדושה ḥavurā qədošā "sacred society", while in Aramaic, חבורתא קדישתא ḥavurtā qaddišṯā. Modern Hebrew "chevra" (chiefly Ashkenazic) is of unclear etymology. The Aramaic phrase is first attested in Yekum Purkan, in a 13th-century copy of Machzor Vitry, but it was rarely used again in print until it gained its modern sense of "burial society" in the nineteenth century. The Hebrew phrase predated it in modern popularity by some decades. Probably the Modern Hebrew phrase is a phonetic transliteration of the Ashkenazic pronunciation of the Hebrew version, which has been misinterpreted as an Aramaic phrase and therefore spelled with a yodh and aleph.

This auspicious title exists because performing a favor for someone who is dead is considered the ultimate act of kindness – as a dead person can never repay the kindness, making it devoid of ulterior motives. Its work is therefore referred to as a chesed shel emet (Hebrew: חסד של אמת, "a good deed of truth"), paraphrased from Genesis 47:29 (where Jacob asks his son Joseph, "do me a 'true' favor" and Joseph promises his father to bury him in the burial place of his ancestors).

See also

References

- Samuel G. Freedman (November 13, 2015). "For Jewish Students, Field Trip Is Window on Death and Dying". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

known as chevra kadisha

- Paul Vitello (December 13, 2010). "Reviving a Ritual of Tending to the Dead". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

- Weisser, Michael R., A Brotherhood of Memory: Jewish Landsmanshaftn in the New World, Cornell University Press, 1985, ISBN 0801496764, pp. 13–14

- Vitello, Paul (August 3, 2009). "With Demise of Jewish Burial Societies, Resting Places Are in Turmoil". The New York Times.

- Catherine Hickley (February 19, 2021). "Auction House Suspends Sale of 19th-Century Jewish Burial Records". The New York Times. Retrieved October 23, 2022.

memorial register of Jewish burials

Further reading

- Chesed Shel Emet: The Truest Act of Kindness, Rabbi Stuart Kelman, October, 2000, EKS Publishing Co. Archived December 18, 2006, at the Wayback Machine, ISBN 0939144336.

- A Plain Pine Box: A Return to Simple Jewish Funerals and Eternal Traditions, Rabbi Arnold M. Goodman, 1981, 2003, KTAV Publishing House, ISBN 0881257877.

- Tahara Manual of Practices including Halacha Decisions of Hagaon Harav Moshe Feinstein, zt'l, Rabbi Mosha Epstein, 1995, 2000, 2005.

External links

- Chesed Shel Emes Website

- Chevra Kadisha Mortuary

- Kavod v'Nichum: Jewish Funerals, Burial, and Mourning

- KavodHameis.org – Chevra Kadisha Training Videos

- Chevra Kadisha of Florida: A Division of Chabad of North Dade

- My Jewish Learning: Chevra Kadisha, or Jewish Burial Society

- National Association of Chevra Kadisha Official Website