Chichijima

Chichijima (父島) is the largest and most populous island in the Bonin or Ogasawara Islands. Chichijima is about 240 km (150 mi) north of Iwo Jima. 23.5 km2 (9.1 sq mi) in size, the island is home to about 2120 people (2021).[1] Connected to the mainland only by a day-long ferry that runs a few times a month, the island is nonetheless organized administratively as the seat of Ogasawara Village in the coterminous Ogasawara Subprefecture of the Tokyo Metropolitan Government. Together with the Volcano and Izu Islands, it makes up Japan's Nanpō Islands.

Native name: Japanese: 父島 | |

|---|---|

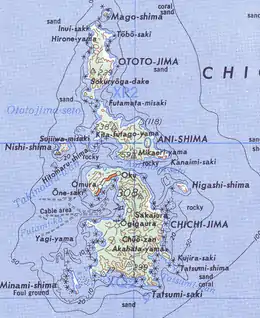

Map of Chichijima, Anijima and Otoutojima | |

Chichijima | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Pacific Ocean |

| Coordinates | 27°4′0″N 142°12′30″E |

| Archipelago | Ogasawara Islands |

| Area | 23.45 km2 (9.05 sq mi) |

| Highest elevation | 326 m (1070 ft) |

| Administration | |

Japan | |

| Prefecture | Tokyo |

| Subprefecture | Ogasawara Subprefecture |

| Village | Ogasawara |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 2,120 (2021) |

| Pop. density | 90.4/km2 (234.1/sq mi) |

| Ethnic groups | Japanese, mixed |

Some Micronesian tools and carvings have been found elsewhere in the Bonins, but Chichijima was long uninhabited when it was rediscovered. Ignored by the Spanish, Dutch, and Japanese Empires for centuries, it was finally claimed by a passing British captain in 1828 and settled by an international group from the Kingdom of Hawaii two years later, the original nucleus of the Ōbeikei ethnic group. Britain subsequently yielded to Japanese claims and colonization of the island, which established two villages at Ōmura (大村) and Ōgimura-Fukurosawa (扇村袋沢村). These were formally incorporated in 1940, just before the civilian population was forcibly evacuated to Honshu in 1944 during the end of the Second World War. After the Surrender of Japan, the United States Armed Forces occupied the islands for two decades, destroying Japanese homes and businesses and only allowing resettlement by the Ōbeikei. Following the resumption of Japanese control in 1968, Home Island Japanese rapidly became the majority again.

Names

The Japanese names of the Bonin Islands are mostly based on family relationships, established by the 1675 expedition under Shimaya Ichizaemon and fully adopted in the 1870s after the onset of Japanese colonization.[2][3] As the largest island in the chain, Chichijima (父島) means "Father Island".[3] It is sometimes written Chichi Jima[4] or Chichi-jima[5] and is also sometimes incorrectly read as Chichishima or Chichitō, based on other pronunciations of the character for "island".

Historically, Chichijima has also been known as Gracht, Graght, or Graft Island (Dutch: Grachts, Graghts, or Grafts Eylandt)[6] after a Dutch ship named for the Netherlands' urban canals; Peel Island after the British home secretary Robert Peel,[7] later prime minister; and the Main Island[4] (and by extension Bonin Island, Bonin Sima, etc.).

History

Prehistory

Some Micronesian tools and carvings have been found on North Iwo Jima and elsewhere in the Bonins,[8] but Chichijima was long uninhabited when it was rediscovered. The Japanese accounts of a discovery by a member of the Ogasawara clan of samurai—the source of the Bonin's Japanese name—are now known to be false.[9][10] Similarly, accounts that Chichijima was discovered by the Spanish explorer Bernardo de la Torre during his failed 1543 voyage are incorrect, De la Torre having at most seen a single island from the Hahajima group at the southern end of the Bonin chain[11] and most likely not even that.[6] Despite the Bonins lying near the northern return route used by the Spanish after , none are recorded landing or charting the islands with any certainty.[6]

Early history

The first certain sighting of Chichijima was by the failed 1639 Dutch expedition sent in search of the phantom Islands of Gold and Silver under Matthijs Quast and his lieutenant Abel Tasman.[6]

A Japanese merchant ship carrying mikan (a kind of tangerine) from Arida was blown off course around 10 December 1669 and shipwrecked on Hahajima 72 days later, about 20 February 1670. The captain dead, the remaining six crew rested, explored, and rebuilt their ship for 52 days and then left (around April 13th) for Chichijima. They stayed there 5 or 6 days, visited Mukojima for a few days, and then reached Hachijojima in the Izu Islands 8 days after that. Once back on Honshu at Shimoda, they reported their (re)discovery in detail to the bakufu.[12] The shipwrights at Nagasaki were then specially permitted to build an ocean-going junk of the "Chinese type", the Fukkokuju Maru. Shimaya Ichizaemon was allowed to use it to trade between Nagasaki and Tokyo for 4 years before being directed to undertake a secret mission to explore and chart the islands with a crew of about 30 in May 1674.[2][13] The attempts in June 1674 and February 1675 both failed but after repairs and waiting for more favorable winds the reached the Bonins on April 29.[13] After erecting a shrine and mapping the chain including Chichijima, Shimaya departed on June 5, reaching Tokyo with his maps and samples of the soil, plants, and animals that he had found.[13] After notionally placing the islands under the jurisdiction of Izu, the sakoku isolationist policy was resumed: the crew was disbanded, the junk broken up, and no further activity was taken or allowed with the islands.[2][13] (It remained uninhabited until 1830.[14])

Western explorers visited the island on at least two occasions in the early 19th century. Frederick William Beechey's Pacific expedition on HMS Blossom in 1827, and Heinrich von Kittlitz in 1828 with the Russian Senjawin expedition, led by Captain Fyodor Petrovich Litke. Two shipwrecked sailors who were picked up by Beechey suggested that the island would make a good stopover station for whalers due to natural springs found on the island.

The first settlement was established in May 1830, by a group formed in Hawaii (which was officially an independent kingdom at the time). The settlers were initially led by Matteo Mazzaro, an Italian-born British subject,[15] included 13 indigenous Hawaiians (from Oahu), another Briton, two US citizens, and a Dane.[15] The UK consul in Hawaii, Richard Charlton, accompanied the group to "Peel Island", and returned immediately to Hawaii; no evidence has bee found that the settlement was officially gazetted as an official UK territory. By 1840, following a power struggle between Mazzaro and Nathaniel Savory, a mariner from Massachusetts, de facto leadership of the settlers passed to Savory.[15] The original settlers were gradually joined by other Americans, Europeans and Pacific Islanders.[15]

Commodore Matthew C. Perry's flagship USS Susquehanna anchored for 3 days in Chichijima's harbor on 15 June 1853, on the way to his historic visit to Tokyo Bay to open up the country to western trade. Perry also laid claim to the island for the United States for a coaling station for steamships, appointing Nathaniel Savory as an official agent of the US Navy and formed a governing council with Savory as the leader. On behalf of the US government, Perry "purchased" 50 acres (200,000 m2) from Savory.[16]

In 1854, naturalist William Stimpson of the Rodgers-Ringgold North Pacific Exploring and Surveying Expedition visited.

1862 – 1941

On 17 January 1862, at Chichijima, Japanese sovereignty over the Ogasawara Islands was proclaimed, following the arrival of an official party from the Tokugawa Shogunate.[8] The existing inhabitants were allowed to remain,[14] and Savory's authority was acknowledged,[17]

Ethnic Japanese gradually outnumbered descendants of the first wave of settlers, whom they referred to as Oubeikei (or Ōbeikei; literally "Westerners"). A unique mixed language, Bonin English, emerged on Chichijima, combining elements of Japanese with English and Hawaiian.

Following the Meiji restoration, a group of 37 Japanese colonists arrived on the island under the sponsorship of the Japanese Home Ministry in March 1876. The island was officially administered by Tokyo Metropolis on 28 October 1880.

A small naval base was established on Chichijima in 1914. Emperor Hirohito made an official visit in 1927, aboard the battleship Yamashiro.

World War II

The island was the primary site of long range Japanese radio stations during World War II, as well as being the central base of supply and communication between Japan and the Ogasawara Islands.[18] It had the heaviest garrison in the Nanpō Shotō. According to one source: "At the time of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, an Army force of about 3,700-3,800 men garrisoned Chichi Jima. In addition, about 1,200 naval personnel manned the Chichi Jima Naval Base, a small seaplane base, the radio and weather station, and various gunboat, subchaser, and minesweeping units."[19][20] The garrison also included a heavy artillery fortress regiment.[21]

During the war, the Oubeikei were viewed with suspicion by the Japanese authorities, which saw them as potential spies.[22] They were reportedly forced to take Japanese names. In 1944, all of the 6,886 civilian inhabitants were ordered to evacuate from the Ogasawara islands to the Home Islands, including the Oubeikei. (However, at least two US citizens of Japanese descent served in the Japanese military on Chichijima during the war, including Nobuaki "Warren" Iwatake, a Japanese-American from Hawaii who was drafted into the Japanese Imperial Army while living with his family in Hiroshima.[14])

Chichijima was a frequent target of US Navy air attacks. The future President George H. W. Bush was shot down while on one of these raids, and rescued from the sea. In the Chichijima incident of February 1945,[14] US aviators who had been captured, were tortured, executed, and in cases, partially eaten. (The air raids became the subject of a book by James Bradley entitled Flyboys: A True Story of Courage.)

Japanese troops and resources from Chichijima were used in reinforcing the strategic point of Iwo Jima before the historic battle that took place there from 19 February to 24 March 1945. The island also served as a major point for Japanese radio relay communication and surveillance operations in the Pacific, with two radio stations atop its two mountains being the primary goal of multiple bombing attempts by the US Navy.[14]

The island was never captured, and at the end of World War II, some 25,000 troops in the island chain surrendered. Thirty Japanese soldiers were court-martialled for class "B" war crimes, primarily in connection with the Chichijima incident and four officers (Major Matoba, General Tachibana, Admiral Mori, and Captain Yoshii) were found guilty and hanged. All enlisted men and Probationary Medical Officer Tadashi Teraki were released within 8 years.[23]

US occupation

The United States maintained the former Japanese naval base and attached seaplane base after the war.

A majority of the pre-war civilian population was initially barred from returning by the SCAP, which allowed only 129 Oubeikei to return, in recognition of their mistreatment by the wartime Japanese authorities. Other houses on the island were destroyed.

Several occupied islands, including Chichijima, were used by the United States in the 1950s to store nuclear arms, according to Robert S. Norris, William M. Arkin, and William Burr, writing for the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (in 2000).[24][25] This was despite the Japanese Constitution being explicitly anti-war.[26] Japan holds Three Non-Nuclear Principles.

In 1960, the harbor facilities were devastated by tsunami after the Great Chilean earthquake.

Since 1968

The island was returned to Japanese civilian control in 1968.[27] At that time, the Oubeikei were allowed to choose either US or Japanese citizenship. Many of those who chose to move to the US continued to regularly return to the island, where some ran businesses during the summer tourist season.[22]

By the early 21st century, almost 200 residents identifying as "Americans" and/or Oubeikei remained on the island.[22]

Topography and climate

Chichijima is located at 27°4′0″N 142°12′30″E. Currently, around 2,000 people live on the island, and the island's area is about 24 km2 (9.3 sq mi).

On English maps from the early 19th century, the island chain was known as the Bonin Islands. The name Bonin comes from a French cartographer's corruption of the old Japanese word 'munin', which means 'no man', and the English translated it to "No mans land" islands.[14]

The climate of Chichijima is on the boundary between a tropical monsoon climate (Köppen Am), a tropical rainforest climate (Köppen Af), and a humid subtropical climate (Köppen Cfa). Temperatures are warm to hot and humid all year round, and have certainly remained between 9.2–34.1 °C (48.6–93.4 °F)[28] owing to the warm currents from the North Pacific gyre that surround the island. Rainfall is, however, less heavy than in most parts of mainland Japan, since the island is too far south to be influenced by the Aleutian Low and too far from mainland Asia to receive monsoonal rainfall or orographic precipitation on the equatorward side of the Siberian High. Occasionally, very heavy cyclonic rain falls, as on 7 November 1997, when the island received its record daily rainfall of 348 mm (13.7 in) and monthly rainfall of 603.5 mm (23.8 in).

| Climate data for Chichijima (1991−2020 normals, extremes 1968−present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.1 (79.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

26.7 (80.1) |

28.4 (83.1) |

30.1 (86.2) |

33.0 (91.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

33.7 (92.7) |

33.1 (91.6) |

32.1 (89.8) |

30.2 (86.4) |

27.5 (81.5) |

34.1 (93.4) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 20.7 (69.3) |

20.5 (68.9) |

21.7 (71.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

25.6 (78.1) |

28.5 (83.3) |

30.4 (86.7) |

30.3 (86.5) |

29.9 (85.8) |

28.6 (83.5) |

25.9 (78.6) |

22.7 (72.9) |

25.7 (78.3) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 18.5 (65.3) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

21.1 (70.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

26.2 (79.2) |

27.7 (81.9) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.7 (81.9) |

26.4 (79.5) |

23.8 (74.8) |

20.6 (69.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.8 (60.4) |

15.4 (59.7) |

16.8 (62.2) |

18.8 (65.8) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.4 (75.9) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.1 (79.0) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.4 (75.9) |

21.6 (70.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

21.2 (70.2) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 8.9 (48.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.2 (48.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

20.8 (69.4) |

22.2 (72.0) |

19.6 (67.3) |

17.2 (63.0) |

13.2 (55.8) |

10.8 (51.4) |

7.8 (46.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 63.6 (2.50) |

51.6 (2.03) |

75.8 (2.98) |

113.3 (4.46) |

151.9 (5.98) |

111.8 (4.40) |

79.5 (3.13) |

123.3 (4.85) |

144.2 (5.68) |

141.7 (5.58) |

136.1 (5.36) |

103.3 (4.07) |

1,296.1 (51.03) |

| Average snowfall cm (inches) | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.5 mm) | 11.0 | 8.5 | 9.8 | 10.0 | 11.8 | 8.8 | 8.6 | 11.3 | 13.4 | 13.7 | 12.0 | 11.2 | 130.2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 68 | 72 | 79 | 84 | 86 | 82 | 82 | 82 | 81 | 76 | 70 | 78 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 131.3 | 138.3 | 159.2 | 148.3 | 151.8 | 205.6 | 246.8 | 213.7 | 197.7 | 173.2 | 139.1 | 125.3 | 2,030.6 |

| Source: Japan Meteorological Agency[29] | |||||||||||||

Island development

Astronomy and telemetry stations

The Japanese National Institute of Natural Sciences (NINS) is the umbrella agency maintaining a radio astronomy facility on Chichijima.[30] Since 2004, the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan (NAOJ) has been a division of NINS.[31] The NINS/NAQJ research is on-going using a VLBI Exploration of Radio Astronomy (VERA) 20 m (66 ft) radio telescope. The dual-beam VERA array consists of four coordinated radio telescope stations located at Mizusawa, Iriki, Ishigakijima, and Ogasawara.[32] The combined signals of the four-part array produce a correlated image which is used for deep space study.[33]

Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency also maintains a facility on Chichijima.[34] The Ogasawara Downrange Station at Kuwanokiyama was established in 1975 as a National Space Development Agency of Japan facility. The station is equipped with radar (rocket telemeter antenna and precision radar antenna) to check the flight trajectories, status, and safety of rockets launched from the Tanegashima Space Center.[35]

JMSDF facilities

From 1968, the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF) has operated the Chichijima Naval Base, along with the associated Chichijima Airfield, the latter including a heliport originally built during the American occupation, as well as seaplane facilities.

Wildlife

Birds

Possibly as a result of the introduction of nonindigenous animals, at least three species of birds became extinct: the Bonin nankeen night heron, the Bonin grosbeak (a finch), and the Bonin thrush. The island was the only known home of the thrush and probably the finch, although the heron was found on Nakōdojima (also "Nakoudo-" or "Nakondo-"), as well. The existence of the birds was documented by von Kittlitz in 1828, and five stuffed thrushes are in European museums. The Bonin wood-pigeon died out in the late 19th century, apparently as the result of the introduction of alien mammals. The species is known to have existed only on Chichijima and another island, Nakōdo-jima. Chichijima, together with neighbouring Anijima and Ototojima, has been recognised as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by BirdLife International because it supports populations of Japanese wood pigeons and Bonin white-eyes.[36]

Green turtle consumption and preservation

The inhabitants of the island traditionally have caught and consumed green turtles as a source of protein. Local restaurants serve turtle soup and sashimi in dishes. In the early 20th century, some 1000 turtles were captured per year and the population of turtles decreased.[37] Today in Chichijima, only one fisherman is allowed to catch turtles and the number taken is restricted to at most 135 per season.[37]

The Fisheries Agency and the Tokyo Metropolitan Government operate a conservation facility on the edge of Futami Harbor.[38] Eggs are carefully planted in the shore and infant turtles are raised at the facility until they have reached a certain size, at which point they are released into the wild with an identification tag. Today, the number of green turtles has been stabilized and is increasing slowly.[37]

Demographics

The original settlers were of Western and Polynesian origin. Their descendants are now known as Obeikei and have Western and Japanese names; they were required to have the latter since World War II. As of 2012, most residents were of Yamato Japanese who came to the island after Japan took back control from the US in the 1970s.[39]

Education

Ogasawara Village operates the island's public elementary and junior high schools.[40]

- Ogasawara Municipal Ogasawara Junior High School (小笠原村立小笠原中学校)[41]

- Ogasawara Elementary School (小笠原小学校)

Tokyo Metropolitan Government Board of Education operates Ogasawara High School on Chichijima.

References

Citations

- "支庁の案内: 管内概要 (Japanese)". 1 April 2021. Retrieved 16 June 2022.

- Kublin (1953), p. 31.

- Eldridge (2008), p. 3.

- Eldridge (2008), p. ix.

- Kublin (1953), p. 27.

- Eldridge (2008), p. 13.

- Eldridge (2008), pp. 3 & 17.

- 小笠原・火山(硫黄)列島の歴史

- Kublin (1953), pp. 29–30.

- Eldridge (2008), p. 11.

- Welsch (2004).

- Eldridge (2008), pp. 13–14.

- Eldridge (2008), p. 14.

- Bradley, James (2003). Flyboys: A True Story of Courage (hardcover) (1st ed.). Little, Brown and Company (Time Warner Book Group). ISBN 0-316-10584-8. Note: Google review

- Mike Coppock, 2021, "American Outpost at Japan’s Front Door", HistoryNet (January 21). (Access : 25 September 2023.)

- New York Herald Tribune "..first piece of land bought by Americans in the Pacific"

- Cholmondeley, Lionel Berners (1915). The History of the Bonin Islands from the Year 1827 to the Year 1876. London: Constable & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 9 September 2014. although he died in 1864. Japanese immigrants were introduced from Hachijōjima under the direction of the Tokugawa Shogunate.

- Japanese Defense Plan for Chichi Jima Peleliu: USMC WWII Combat website

- Western Pacific Operations; History of U.S. Marine Corps in World War II - Part VI Iwo Jima Historical Branch, G3 Division, Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps

- CoastDefense (Yahoo Groups)

- Chichi Jima The Pacific War Online Encyclopedia

- Fackler, Martin (9 June 2012). "Fewer Westerners Remain on Remote Japanese Island". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 August 2019.

- Welch, JM (April 2002). "Without a Hangman, Without a Rope: Navy War Crimes Trials After World War II" (PDF). International Journal of Naval History. 1 (1). §Cannibalism. Retrieved 3 December 2007.

- Robert S. Norris, William M. Arkin and William Burr, "Where they were: How much did Japan know?" Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, January/February 2000

- Robert S. Norris, William M. Arkin and William Burr, "Appendix B: Deployments by country, 1951-1977", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, November/December 1999

- Constitution of Japan - Chapter II, Renunciation of War

- Bowermaster, David (5 December 2009). "Dolphin dances, WWII relics in blissful, remote Japanese islands". Seattle Times. Retrieved 31 July 2009.

- 観測史上1~10位の値(年間を通じての値)

- 気象庁 / 平年値(年・月ごとの値). Japan Meteorological Agency. Retrieved 19 May 2021.

- Ogasawa, VERA astronomy station.

- NAOJ folded into NINS (2004).

- "VERA stations and the array". Archived from the original on 12 June 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- VERA system, radio astronomy

- "JAXA, about the agency". Archived from the original on 6 September 2006. Retrieved 9 March 2008.

- JAXA, Kuwanokiyama facility.

- "Chichijima Islands". BirdLife Data Zone. BirdLife International. 2021. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- 2006年度 活動報告書 Archived 8 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, NGO group Everlasting Nature

- "Ogasawara Marine Center". Archived from the original on 17 April 2010. Retrieved 19 June 2009.

- Fackler, Martin (10 June 2012). "A Western Outpost Shrinks on a Remote Island Now in Japanese Hands". The New York Times. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- "学校教育 Archived 2018-03-09 at the Wayback Machine." Ogasawara, Tokyo. Retrieved on 8 March 2018.

- "小笠原村立小笠原中学校". www.ogachu.que.ne.jp (in Japanese).

Bibliography

- Eldridge, Robert D. (2008), Iwo Jima and the Bonin Islands in U.S.–Japan Relations: American Strategy, Japanese Territory, and the Islanders In-Between (PDF), Quantico: Marine Corps University Press.

- Kublin, Hyman (March 1953), "The Discovery of the Bonin Islands: A Reexamination" (PDF), Annals of the Association of American Geographers, vol. 43, Milton Park: Taylor & Francis, pp. 27–46, JSTOR 2561081.

- Welsch, Bernhard (June 2004), "Was Marcus Island Discovered by Bernardo de la Torre in 1543?", Journal of Pacific History, vol. 39, Milton Park: Taylor & Francis, pp. 109–122, doi:10.1080/00223340410001684886, JSTOR 25169675, S2CID 219627973.